Transformative Services and Transformation Design

Daniela Sangiorgi

ImaginationLancaster, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK

This article reports on the recent evolution of service design toward becoming transformational. Services are less discussed as design objects and more as means for supporting the emergence of a more collaborative, sustainable and creative society and economy. The transformative role of design is combined with the potential transformative role of services. The term “transformation design” as set forth by Burns, Cottam, Vanstone, and Winhall (2006), has been associated with work within communities for socially progressive ends, but also with work within organisations to introduce a human-centred design culture. The intrinsic element of co-production of services in transformation design necessitates the concomitant development of staff, the public and the organisation. In this way, service design is entering the fields of organisational studies and social change with little background knowledge of their respective theories and principles. This article proposes the adoption and adaptation of principles and practices from organisational development and community action research into service design. Additionally, given the huge responsibilities associated with transformative practices, designers are urged to introduce reflexivity into their work to address power and control issues in each design encounter.

Keywords – Service Design, Transformative Services, Transformation Design, Transformational Change.

Relevance to Design Practice – Service design is increasingly oriented toward transformative aims. The concept of transformation design has been proposed, but little research exists on its principles, methodologies and qualities. This article aims to provide some foundations for clarifying the concept of transformational change and suggests a potentially useful bridge with the principles and practices of organisational development and community action research.

Citation: Sangiorgi, D. (2011). Traansformative services and transformation design. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 29-40.

Received December 1, 2010; Accepted April 30, 2011; Published August 15, 2011.

Copyright: © 2011 Sangiorgi. Copyright for this article is retained by the author, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

Corresponding Author: d.sangiorgi@lancaster.ac.uk

Dr. Daniela Sangiorgi is a lecturer at ImaginationLancaster, the creative research laboratory at the Lancaster Institute for Contemporary Arts (Lancaster University, UK). As one of the early scholars looking into service design, she has gained international recognition. Her work has been mapping and supporting this emerging field of study and research since its outset. Her doctorate research investigated services as complex social systems, proposing holistic and participatory approaches to service design. Her recent work has centered on exploring the role of design and participation within public services reform, with a focus on commissioning for healthcare. She was one of the founders of the Service Design Network and Service Design Research initiatives.

Introduction

Service design has recently been developing by enhancing its capacity to facilitate change within both organisations and communities. Burns, Cottam, Vanstone, and Winhall (2006) defined this area of practice as transformation design. According to their definition, the concept of transformation design suggests that:

Because organisations now operate in an environment of constant change, the challenge is not how to design a response to a current issue, but how to design a means of continually responding, adapting and innovating. Transformation design seeks to leave behind not only the shape of a new solution, but the tools, skills and organisational capacity for ongoing change (p. 21).

The fact that transformation design is aiming at radical change is also emphasized. They suggest that transformation design can be applied to radically change public and community services, working for socially progressive ends, or can, alternatively, trigger change in a private company introducing a human-centred design culture.

Furthermore, service design has recently been considering services less as design objects and more as means for societal transformation. The intrinsic element of co-production of services in transformation design necessitates the concomitant development of staff, the public and the organisation. This is particularly evident in the debate around the reform of public services where both organisations and citizens are asked to evolve and adapt to more collaborative service models, thereby changing their roles and interaction patterns (Parker & Parker, 2007). In this way, service design is entering the fields of organisational development and social change, with little background knowledge of their respective theories and principles. In this light, the questions which arise are: How can designers working with communities affect and transform organisations or, vice versa, how can designers working within organisations affect and positively transform user communities? It is also necessary to clarify the form of transformations, why these are desirable and who will particularly benefit from them.

This article aims at providing a first framework for transformation design, in the specific context of public services reform, by suggesting the adoption of key concepts and principles derived from research fields that have focused for decades on the issues of transformational change within organisations and communities, such as organisational development and community action research. Participatory action research has been chosen in particular as a possible integrating methodological framework that characterises both research fields of organisational development and community action research, and which could be adapted to the needs of service design practice.

The following section will clarify the concepts of transformative services, transformation design and transformational change to provide a background knowledge. The article will then introduce a selection of principles from the relevant fields of operational design and community action research and compare them with the principles guiding the transformation of public services and the evolution of participatory design practices within the public sphere.

Transformative Services

At its onset, service design has focused on services as different kinds of products, exploring modes of dealing with the differentiating service qualities (originally thought of as deficiencies) such as intangibility, heterogeneity, inseparability, and perishability (Zeithaml, Parasuraman, and Berry, 1985).

The design debate then made one step forward when acknowledging the nature of services as complex and relational entities that cannot be fully designed and pre-determined (Sangiorgi, 2004). The focus on service interactions has been broadening to consider interactions within and among organisations, working on the systems and networks therein, while designers have been increasingly approaching issues of organisational and behavioural change (Sangiorgi, 2009). In this evolution design for services, instead of service design, has gained more credibility, reflecting the interdisciplinary and emergent qualities of this discipline (Kimbell, 2009; Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011).

In the last few years, a further shift seems to be happening as services are no longer conceived of as an end in themselves, but are increasingly considered as an engine for wider societal transformations. Services are less discussed as a design object, but now more as means for supporting the emergence of a more collaborative, sustainable and creative society and economy. Particular emphasis has been given to collaborative service models and co-creation (Cottam & Leadbeater, 2004; Meroni, 2007).

This evolution is mirrored in the debate around the role of services in developed countries’ economies. Together with a growing acknowledgment of the role of services for the development and growth of economy and employment, services have revealed a different model of innovation that is now inspiring manufacturing; as Howells (2007) comments, this model is ill represented by linear positivistic descriptions and is “more likely to be linked to disembodied, non-technological innovative processes, organisational arrangements and markets” (p. 11). The main sources of innovation in service industries are employees and customers (Miles, 2001) and new ideas are often generated through the interaction with users (user-driven innovation) and through the application of tacit knowledge or training rather than through explicit R&D activities (Almega, 2008). Moreover, service innovation is increasingly viewed as an enabler of a “society driven innovation” with policies at national and regional level that are “using service innovation to address societal challenges and as a catalyst of societal and economic change” (European Commission, 2009, p. 70). Tekes, the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation, positions service innovation as a core lever for transformative changes in areas such as health and wellbeing, clean energy, built environment, and the knowledge society (Ezell, Ogilvie, & Rae, 2008).

Finally, in a recent study the Arizona State University’s Center for Services Leadership collectively identified a set of global, interdisciplinary research priorities focused on the service science (Ostrom et al., 2010). Among ten overarching research priorities, a significant area of present interest emerged titled “Improving Well-being through Transformative Service.” Laurel Anderson (a leader in this field from Arizona State University) described the emerging area of transformative service research as “service research that centers on creating uplifting changes and improvements in the well-being of both individuals and communities” (p. 6). She suggested that services, being deeply embedded and diffused in social ecologies, have the potential to impact individuals, families and communities by suggesting new behavioural and interaction models. This area, of particularly contemporary relevance, has been given little attention to date.

Transformation Design

Design, additionally, has recently focused increasingly on investigating the transformative role of services as a way to build a more sustainable and equitable society. Main fields of research have been related to the exploration of the role and impact of creative communities and social innovation (Jegou & Manzini, 2008; Meroni, 2007; Thackara, 2007) and the wide debate on the redesign of public services and the welfare state (Bradwell & Marr, 2008; Cottam & Leadbeater, 2004; Parker & Heapy, 2006; Parker & Parker, 2007; Thomas, 2008).

The research on social innovation has been investigating existing examples of inventiveness and creativity among “ordinary people” to solve daily life problems related to housing, food, ageing, transports and work. Such cases represent a way of “living well while at the same time consuming fewer resources and generating new patterns of social cohabitation” (Manzini, 2008, p. 13). Defined as “collaborative services,” they have the potential to develop into a new kind of enterprise, a “diffused social enterprise” which needs a supporting environment to grow.

The contemporary debate on the re-design of public services has similarly emphasised the role of co-production and collaborative solutions. With the co-creation model, Cottam and Leadbeater (2004) suggested examining the open source paradigm as the main inspiration, which implies the use of distributed resources (know-how, tools, effort and expertise), collaborative modes of delivery, and the participation of users in “the design and delivery of services, working with professionals and front-line staff to devise effective solutions” (p. 22). This, in turn, requires a significant transformation in both organisations and citizens’ behaviors and engrained cultural models.

Simultaneously, design research has recently been exploring design’s transformative role in both organisations (Bate & Robert, 2007a, 2007b; Buchanan, 2004; Junginger, 2008; Junginger & Sangiorgi, 2009) and communities (Thackara, 2007). Service design practitioners have been moving from providing solutions to specific problems, to providing organisations with the tools and capacities for human-centred service innovation. Examples of this include the work of Engine Service Design group with Kent City Council to develop a Social Innovation Lab (Kent County Council, 2007) or the work with Buckinghamshire to define a methodology for the engagement of local organisations and citizens (Milton, 2007).

Similarly, the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement has developed the Experience-Based-Design (EBD) approach and toolkit in collaboration with thinkpublic (a London based service design studio) to co-design more accessible, usable and effective services. They have organised a series of training workshops and pilot projects to support adoption on a wider scale. Since its launch in 2007, the EBD approach, consisting of experience-focused participatory design exercises, has been piloted in various hospitals with the aim of activating a large-scale cultural change in NHS.

This evolution within design has been intuitively defined in its emergence as transformation design by Burns et al. (2006). They summarise the key characteristics of transformation projects as follows: 1) defining and redefining the brief, as designers engage before the definition of the brief and participate in the formulation of the right problem to tackle; 2) collaborating between disciplines, as the complexity of contemporary challenges requires multidisciplinary efforts; 3) employing participatory design techniques, as users and front-line workers can bring in their ideas, expertise and knowledge; 4) building capacity and not dependency, as transformation projects aim to leave the capacities and skills for ongoing change; 5) designing beyond traditional solutions, as designers focus on changing behaviour (and not only forms) and need to tackle issues with a more holistic perspective; 6) creating fundamental change, as projects can initiate a lasting transformation process, leaving a vision and champions to continue the work.

These characteristics bring some challenges as designers are not necessarily trained to work on highly complex issues or to direct their work toward transformational aims. The traditional design consultancy may need to change its practice and relationship with clients and reconsider its identity within design interventions. Also, an understanding of appropriate methodologies and an articulation of key design principles are still missing. When designers engage in transformational projects they have a huge responsibility, especially when engaging with vulnerable communities. In addition, the quality and effectiveness of such interventions are hard to evaluate in the short term and within traditional design parameters. To better understand the modes and outcomes of transformational projects, the first (and most basic) question to ask is: What is it a transformational change?

Transformational Change

In organisational development, change is discussed and evaluated in terms of degrees or levels. Early studies from Watzlawick, Weakland, and Fisch (1974) identified two levels of change as first-order and second-order change. First-order change was related to adjustments and fluctuations within a given system, while second-order change implied qualitative changes to the system itself. In a similar way, Golembiewski, Billingsley, and Yeager (1989) introduced three levels of change in the context of change measurement: alpha change, related to changes in perceived levels of variables within a given paradigm; beta change, related to changes in standards and perception of value within a given paradigm; and gamma change, related to the change of the paradigm itself. Looking at biology, Smith (1982) suggested comparing the terms morphostasis and morphogenesis, where the former indicates changes in appearance and maturation processes of an organism, while the latter indicates a change in the genetic code, in the core and essence of it. Organisational development studies in 1960s and 1970s focused on first order changes focusing on improving “the internal working of organisations through the use of role clarification, improved communication, team building, intergroup team building, and the like” (French, Bell, & Zawacki, 2005, p. 7). In 1980s, the external environment changed marked by growing competition with more demanding customers and an instable economy. Companies were asked to change fast to survive. The kind of change required, however, was not incremental, but rather very radical.

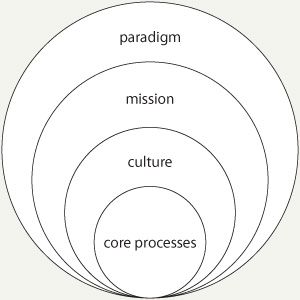

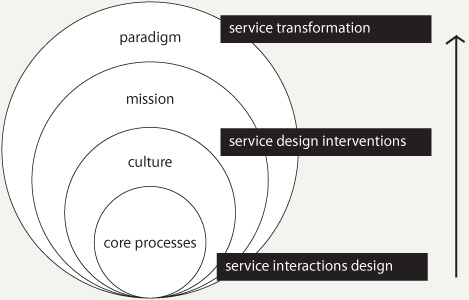

Organisational transformation emerged as a specific area of research to better understand the drivers, processes and content of planned, second-order change, defined as transformational change. Levy (1986) claims that second order change is a “paradigmatic change” and that in order to support this transformational change, one has to change the “metarules” (the rules of the rules) of the system. He visualises an integrated model of the perspectives of what is changed in a second-order change, moving from core processes, culture, mission and paradigm (see Figure 1). In order to achieve a paradigmatic change that entails change in the core assumptions and world view of an organisation, companies need to change all the other levels, including the organisational philosophy, mission and purpose, culture and core processes. Changes in the organisational mission or culture do not imply necessarily a paradigmatic transformation. Seen from a service design perspective, projects that improve service interactions and touchpoints (service interaction design) or that help redefining service values, norms or philosophy (service interventions), don’t necessarily have a transformational impact (see Figure 2). Uncovering and questioning, via design inquiries, core assumptions and organisational worldviews, can have, instead, a far-reaching impact into organisational evolution (Junginger & Sangiorgi, 2009).

Figure 1. Contents of second-order change (source: Levy, 1986, p. 16).

Figure 2. Levels of change within service design practice

(adapted from Junginger & Sangiorgi, 2009).

How this can happen, however, has not yet been discussed in service design research. Junginger (2006), in her investigations into the role of design for organisational change, suggests a link between human-centred design and organisational learning:

For an organization, human-centered design offers two key benefits: Firstly, it centers product development on the needs of its customers. Secondly, applying user research methods can reveal the strengths and weaknesses of an organization’s interaction with different customers and employees. The findings can serve as a base for an organizational redesign by understanding existing and future relationships within the organization’s network from a user perspective (p. 10).

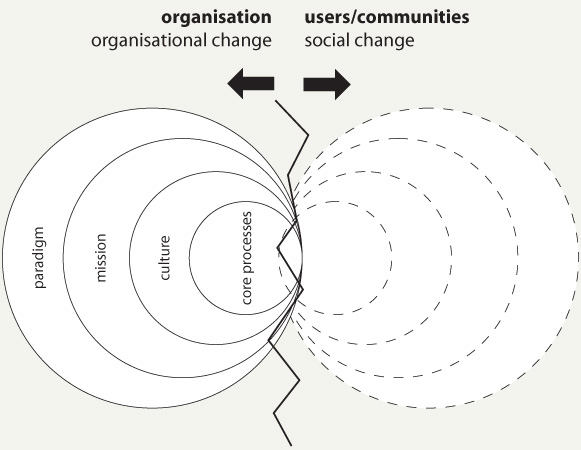

Nonetheless, as mentioned previously, looking at transformational processes within service organisations is only one side of the coin. Users and communities, that co-produce service activities, might need to go through similar transformational processes as shown in Figure 3. This is particularly true if we look at the deep transformation being advocated in public services, which involves moving from a delivery model that is associated with a paternalistic and top down welfare paradigm, toward an enabling model that is centred on the concept of co-creation and active citizenship. Designers have been adopting two main kinds of transformation strategies with public services (Freire & Sangiorgi, 2010). The first is change from inside-out, working within organisations to instill a human-centred design culture and improve service provisions. The other is change from outside-in, or working with communities and various stakeholders to imagine new systems and service models. Both of these strategies need grounding through understanding change and transformational practices. Working on one side only, without considering potential resistances in both communities and organisations, can lead to failure or achievement of a limited impact. In light of this, designers should learn from studies and projects of organisational development and community action research to provide a more solid foundation on which to build their activities.

Figure 3. Second-order change in service encounters.

Transformative Practices and Principles

A methodological framework that unifies transformational interventions within organisations and communities is participatory action research. Action research is generally associated with the experimental work of Kurt Lewin in the 1940s on social democracy and organisational change. Kurt Lewin said once that “if you want to understand a phenomenon, try to change it” (French et al., 2005, p. 106). His approach is part of “normative-reeducative strategies of changing” that consider intelligence as social rather then narrowly individual, and consider people as guided by a “normative culture” (Chin & Benne, 2001). As they elucidate:

Changes in patterns of action or practice are, therefore, changes, not alone in the rational information equipment of men, but at the personal level, in habits and values as well and, at the sociocultural level, changes are alterations in normative structures and in institutionalized roles and relationships, as well as in cognitive and perceptual orientations (p. 47).

Action research has been defined as a:

Participatory, democratic process concerned with developing practical knowing in the pursuit of worthwhile human purposes . . . It seeks to bring together action and reflection, theory and practice, in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions to issues of pressing concern to people. And more generally the flourishing of individual persons and their communities. (Reason & Bradbury, 2001, p. 1)

Action research is about generating practical knowledge that can help improve the wellbeing of individuals and communities. It is based on a postmodern conception of knowledge as a social construct and on the recognition of the intimate relationship between knowledge and power (Reason & Bradbury, 2001). Participatory action research provides a framework, which allows a heterarchical rather than hierarchical approach to research. Doing so, it allows a diversity of opinions and possibilities rather than a forced consensus from a reductionist approach to research. This produces a “power to” effect by empowering those involved in the study, as opposed to a “power over” dominance of the active and knowledgeable researcher over the passive subject of the research (Hosking, 1999).

Action research has been applied and developed in a variety of fields and at different levels, especially in the areas of management, education and development studies. Particularly relevant to the present article is the application of participatory action research with marginalized groups and disadvantaged communities. This application called community action research stated how the researcher neutrality of the traditional scientific approach was inadequate to transform dependency and question inequities. Consciousness-raising or “conscientization” is the central concept of community action research. It is intended as a self-reflection and awareness process that leads from seeing oneself as an object responding to a given system to a subject that can question and transform the system itself (as cited in Ozanne & Saatcioglu, 2008)1. Also, community action research has been focused particularly on issues of health and wellbeing and is therefore strongly linked to the field of public health research and issues of community empowerment.

Transformation design, with its emphasis on participation and empowerment, can be related to action research, even if it has not developed any particular reflection on its relationship with knowledge generation, power and change. More traditionally concerned with issues of power and control is participatory design, which is mentioned as a key component within transformation design practices. Participatory design has moved from working within organisations (private companies and public service organisations) to emphasizing support for democratic processes of change within communities and public spaces, with the intention of enhancing egalitarian practices of innovation and community empowerment (Ehn, 2008).

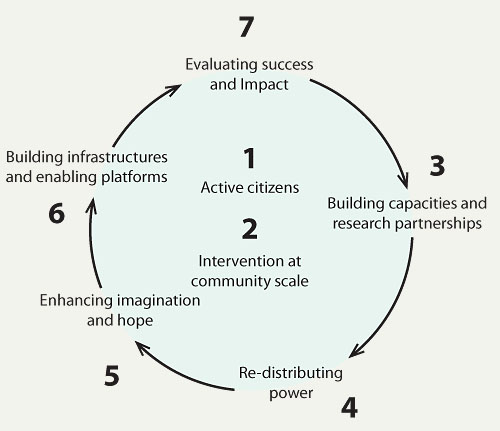

Based on these analogies and comparisons of the literature from these different fields, the present research has identified seven key principles (see Figure 4) that seem to unify transformative practices in design, organisational development and community action research with a particular focus on issues of public service reform and wellbeing. The seven key principles are: 1) Active citizens; 2) Intervention at community scale; 3) Building capacities and project partnerships; 4) Redistributing power; 5) Designing infrastructures and enabling platforms; 6) Enhancing imagination and hope; 7) Evaluating success and impact. What follows is an articulation of the content of the principles to enable reflection on the implications for service design practice within transformative projects.

Figure 4. Transformational principles.

Active Citizens

The central condition for transformative practices is the understanding of citizens as “agents” and their active role in the creation of wellbeing. As Bentley and Wilson (2003) argue, the key to unlock the potential to offer better and more personalised services is to understand that value is created, and not delivered. At the same time, participation has been promoted as being the basic right of democracy, which is a process leading toward better citizens and a means of generating more efficient and effective programmes and policies (Cornwall, 2008).

In the design debate about public services transformation, participation is seen as a key resource to fundamentally change the traditional hierarchical model of service delivery and the perception of citizens themselves. Cottam and Leadbeater (2004) proposed an alternative approach to the welfare system defined as Open Welfare. The authors suggested an open model to public services delivery based on “mass, participatory models, in which many of the ‘users’ of a service become its designers and producers, working in new partnerships with professionals” (p. 1).

In line with this perspective, the reform of healthcare services calls for “creating a Patient-Led NHS” (Department of Health, 2005). The claimed aim here is to change the whole system so that “there is more choice, more personalised care, real empowerment of people to improve their health,” and to “move from a service that does things to and for its patients to one which is patient-led, where the service works with patients to support them with their health needs” (p. 3).

Participation, however, can have different levels of implementation and motivations at its starting point. When participation is pushed to its extremes it meets other agendas generally named as community or citizen “empowerment” and it is linked with more “transformative” aims. Participation here becomes a mean and an end in itself (White, 1996).

A recent review (Marmot, 2010), combining reflection on health inequalities and community engagement, suggests that to really reduce health inequalities, a strong emphasis must be given to individual and community empowerment, which would create the conditions for people to take control over their lives. This requires, on the local service delivery side, increasing the opportunities for people to participate in the definition of community solutions, thus enabling a real shift of power. Marmot contends that “without citizen participation and community engagement fostered by public service organisations, it will be difficult to improve penetration of interventions and to impact on health inequalities” (p.151).

Primary care services are required to “develop and adopt inclusive practice that seeks to empower patients and develop their health literacy” (p. 157). Research has shown how moving from a patient information or consultation approach toward more inclusive and participatory methods (supporting a real shift of power and participation in health decisions) may lead to better health outcomes (Attree & French, 2007). An increase in participation can lead to more appropriate and accessible services, while increasing social capital and people’s self confidence and health-enhancing attitudes (Popay, 2006).

Within organisational development studies, a strong emphasis is given to participatory research and learning processes within organisations seen as drivers for transformational change. The “reframing” needed to deepen transformations cannot happen without a deep psychological engagement among stakeholders (Chapman, 2002). Also connected to transformational change is the concept of empowerment, where project participants are not only consulted during different phases of the transformation process, but they act as co-creators. In this way, to be empowering, participation needs to become a form of “codetermination” (Elden & Levin, 2001). This level of worker-engagement is defined as “organisational citizenship.” Citizenship here is seen both as an obligation and as an expectation, given the organisational constraints. In this sense, collaboration in organisational transformation projects is perceived as a top-down process that includes workers’ insights, while working within an existing social order. Within community action research, however, citizenship is described as a right, where participation is part of an awakening self-reflective process that questions existing power and societal structures and aims at change as an often conflicting bottom up movement (Ozanne & Saatcioglu, 2008).

Intervention at Community Scale

Another precondition for transformative practices is the focus on communities as intervention scale. Communities are considered as the right size to activate large-scale changes. Meroni (2008) promotes the concept of a Community Centred Approach “where the focus of attention shifts from the individual ‘user’ to the community as the new subject of interest for a design that is more conscious of current social dynamics” (p. 13). Communities, or the dimension of “some”, are described as the dimension of change where “elective communities (defined by interest, geography, profession or other criteria) are sufficiently larger than the individual to impose moral restraints that transcend the individual will, but still small enough to be recognised as representative of individual interests” (p. 14).

Within business contexts, community action research is a collaborative process of knowledge creation that engages a wider community of practitioners, consultants and researchers to activate large-scale transformational change (Senge & Scharmer, 2001). It is based on the assumption that the high level of competition that has characterised the industrial era needs now to be tempered with cooperation. Community action research interventions therefore foster relationships and collaborations beyond individual organisations, which create cross-organisational learning communities that, can generate and sustain transformative changes (Senge & Scharmer, 2001). Moreover, in public health, the prevention of lifestyle illnesses, to be effective, requires large-scale community participation and measures (Blumenthal & Yancey, 2004). At the same time, the design of future healthcare services is increasingly connected to integrated and community-based solutions (Department of Health, 2008b).

Building Capacities and Project Partnerships

Participatory and community based interventions have in themselves, if carefully supported, the potential to be transformative. As Cornwall (2008) claims, though, to be effective participation “requires changes in organisational culture, as well as in the attitudes and behaviour of state officials and service providers. It also demands processes and structures through which citizens can claim voice, and gain the means to exercise democratic citizenship, including acquiring the skills to participate effectively” (p. 14).

In public health research, the terms “participation” and “public involvement” are better understood as “building relationships” (Anderson, Florin, Gillam, & Mountford, 2002), and about creating “involved organisations” (Department of Health, 2008a) where patient engagement is integrated into the decision-making processes. The emphasis is therefore not only on developing external “mechanisms of involvement,” but also on implementing internal “mechanisms of change” (Anderson, Florin, Gillam, & Mountford, 2002). This comes from the awareness that for any transformation to be sustainable and effective in the long term, there needs to be a change of cultures and attitudes by building trust and on-going dialogues. One-off interventions in a constantly changing political and socio-technical environment cannot generate significant results in terms of reduction of health inequalities and service improvements (Bauld, Judge, Barnes, Benzeval, & Sullivan, 2005). It is therefore fundamental to create a culture of participation and involvement that can last beyond changes in political objectives and strategies.

Community action research has three guiding principles: 1) to include multiple partners from the community in the research process and generate research partnerships; 2) to be guided by locally-defined priorities and committed to social justice; 3) to aim at community education and empowerment by encouraging people to learn new skills, reflect on their social and economic conditions, and act in their own self interest (Ozanne & Anderson, 2010).

Transformation design has similarly inherited the participatory design principle (Shuler & Namioka, 1991) of learning and transcending, which brings about a reciprocal learning process between designers and project participants leading to transformative understandings. If, however, participatory design focuses on providing tools for an adequate participation to guarantee shared ownership of the final design outcome, the transformational perspective aims also at the final ownership of the process and methods themselves.

When design encounters organisational and behavioral change, pilot projects become vehicles for knowledge exchange within longer transformational processes. An example is Thinkpublic, which tackled dementia as part of the DOTT07 programme. The organisers hosted a Skills Share Day with a cameraperson from the BBC providing training for filming and interviewing a user group. As a secondary outcome of this endeavor, key stakeholders participating in the project acknowledged how the communication skills they acquired during the project were transferred into their daily professional lives (Tan & Szebeco, 2009).

As discussed here, building capacities and trusting relationships are fundamental to generate lasting legacy in transformative practices. The next question to consider, however, is when knowledge exchange is conducive to real transformations.

Redistributing Power

Participation in a design process does not depend necessarily on the set of methods used or skills transferred, but on the actual redistribution of power happening in the design decision process. Arnstein (1969), in his famous reflection on citizen participation, talks about eight rungs in the “ladder of participation”. The rungs begin at the bottom with non-participation, which incorporates actions such as “manipulation” and “therapy”. The next rung is tokenism, which incorporates such actions as “informing”, “consultation” and “placation”. The top rung is citizen power, articulated as “partnership”, “delegated power” and “citizen control”. Non-participation is associated with attempts to educate and persuade the population of the benefit of existing plans and programmes, while tokenism gives citizens a voice that lacks power to guarantee its follow-through. Citizen power suggests situations where citizens are actually given the structure, skills and support to really participate in decision processes.

In a similar way, Popay (2006), reporting on the practices of community engagement, suggests four broad approaches that are mainly differentiated by their engagement goal: the provision and/or exchange of information, consultation, co-production, and community control. She highlights that “these approaches are not readily bounded but rather sit on a continuum of engagement approaches with the focus on community empowerment becoming more explicit and having greater priority to the right of the continuum where community development approaches are located” (pp. 6-7).

Bate and Robert (2009) suggest an ideal move in the continuum of patient influence from “complaining” and “giving information” toward “listening & responding”, “consulting & advising” and “experience-based co-design”. Here, co-design is intended as “more of a partnership and shared leadership, with NHS staff continuing to play a key role in leading service design alongside patients and users” (p. 10). Here, professionals maintain the lead in the change process, while patients are represented as experts of their own experiences.

In this continuum, the roles of researchers and professionals gradually change. A first consideration relates to what each project participant brings to the process; researchers are said to bring their expertise mainly in methods and theories, while people from the community contribute with insights into “theories-in-use”, their capacities and needs, and with their implicit understanding of community social and cultural dynamics (Ozanne & Anderson, 2010). Skidmore and Craig (2005), in their celebration of the role of community organisations for citizen activation, talk about “civic intermediaries” as actors that don’t have necessarily a predefined aim, but work with “communities of participation” to enhance their skills, willingness and capacities to contribute to whichever public or semi-public spaces they engage with. In the design field there is a growing consent about the role of designers as facilitators of change processes, but there is a division as to who is actually directing the process, moving between design-driven or use-driven (or led) change processes.

In participatory action research, researchers challenge the traditional division of power in research relationships, where few people in academia and industrial laboratories control the production of “scientific knowledge”. The transformation process is actually defined as a “cogenerative learning process” where researchers (outsiders) and clients (insiders) are both defined as “colearners” (Elden & Levin, 2001) and not as “experts” or “subjects”. This collaborative learning process can lead to the re-formulation of a “local theory” that can help insiders to re-think their work and worldview and outsiders to generate more general (scientific) theory. This is based on the conception of knowledge as socially constructed (Berger & Luckmann, 1966), where both scientific and personal theories of the world are social products that can be investigated, tested and changed if necessary. However, as in design, with participatory action research the “control dilemma” is still present, because even if participants should be in charge of the research process, the researchers can’t loose control completely (Elden & Levin, 2005).

Building Infrastructures and Enabling Platforms

When the final aim is a transformative one, not only the process, but also the outcome needs to better consider people’s participation and engagement. Public Services have emphasised the concept of co-production as the key strategy for more effective and personalised services (Horne & Shirley, 2009). Considering people’s role in shaping and contributing to the service delivery and constant redesign requires thinking not only of the role of users in the design “before the use”, but also in the design “after the design” (Ehn, 2010). Pelle Ehn, reflecting on the evolution of participatory design practices, suggests that “rather than focusing on involving users in the design process, focus shifts towards seeing every use situation as a potential design situation. So there is design during a project (‘at project time’), but there is also design in use (‘at use time’)” (p. 5).

At project time, the object should then be open to controversies or reiterations that could support the emergence of new products and practices. Using a Leigh Star concept, Ehn talks about “infrastructing” which he discusses by noting that “an infrastructure, like railroad tracks or the Internet is not reinvented every time, but is ‘sunk into’ other sociomaterial structures and only accessible by membership in a specific community-of-practice” (p. 5).

In a similar way, when describing the relevance of community organisations to support people’s participation and engagement, Skidmore and Craig (2005) recall the capacities of these organisations to build:

a platform capable of sustaining diverse and sometimes even incoherent sets of activities … The result of taking the platform model seriously is that it can become very difficult to know where the boundaries of organisations start and finish. Embedded in a web of relationships of varying types, it makes more sense to think of organisations in terms of the networks through which they work. (p. 48)

The concept of designing service platforms is also part of the transformation design language. When project participants become co-creators of the service, designers cannot design fixed entities and sequences of actions that allow little adaptation and flexibility. Platforms made up of tools, roles and rules delineate the weak conditions for certain practices and behaviours to emerge (Sangiorgi & Villari, 2005; Winhall, 2004). At the same time, when designers are confronted with the need to diffuse and scale up creative communities’ promising solutions, their contributions take the form of “enabling solutions” which are “a system of products, services, communication and whatever is necessary, to improve the accessibility, effectiveness and replicability of a collaborative service” (Manzini, 2008, p.38).

In community action research, emphasis is on co-creating sustainable locally grown solutions that are based on community strengths and that locals are willing to maintain and further develop. Without this attention, community action research could hardly reach its main aim, which is to conduct research interventions for the benefit of the communities with which researchers work (Ozanne & Saatcioglu, 2008).

Enhancing Imagination and Hope

Part of a process of change is the capacity to imagine a possible and better future. Designers are generally appreciated for their capacity to think out of the box by providing new visions for the future. As Meroni reminds us, mentioning the work of Bateson (Mind & Nature, 1979), evolution is different from “epigenesis” which is “the development of a system from a previous condition using the capabilities it already possesses” (Meroni, 2008, p. 5). If “epigenesis” means predictable repetition, which grows from within, evolution requires instead exploration and change. Designers are considered to act at this second level as they can work from the outside in and guide more systemic interventions if needed. Enhancing the capacity to build new shared and orienting visions is a fundamental quality in transformation processes (Manzini & Jegou, 2003).

In addition to developing a vision, however, communities need to trust their actual capacity and power to implement it in the future. Skidmore and Craig (2005) claim that “without the hope that animates social networks … social capital can go to waste. The networks people have are only as valuable as what they believe they can accomplish through them” (p. 61). This combination of social networks and collective optimism has been called by the American sociologist Robert Sampson “collective efficacy” (as cited in Skidmore & Craig, 2005). Activating collective optimism through shared and orienting visions needs to be supported by the creation of adequate infrastructures and effective power distribution strategies.

Similarly, organisational change is based on radical transformations in the way individuals think and behave. Levy and Merry (1986) talk about two main strategies. The first is “reframing” which aims at changing the way employees perceive reality. The other is “consciousness raising” which aims at increasing the employee’s understanding of change processes and the creative methods to achieve them.

Evaluating Success and Impact

Finally, one of the key issues when designing for long-term transformation processes is evaluation. How can you measure success and impact in a complex system? What are the dimensions of success? When transformation is related to cultural and worldview change, how do you evaluate it? Or when transformation is related to community empowerment, wellbeing, and social capital, how can you measure it?

Quality in action research is measured looking at five types of validity (Reason & Bradbury, 2001): outcome validity, democratic validity, process validity, catalytic validity, and dialogical validity. Outcome validity is related to an actual improvement of human welfare and relevant problem resolution. Democratic validity depends on the level all the relevant stakeholders potentially affected by the project, participate in the problem definition and solution. Process validity looks at how the project allows for learning and improvement of participants. Catalytic validity looks at how participants have been actually empowered by the process to understand and change reality within and beyond the research study and how the local knowledge could be applied on a wider scale. Finally, dialogical validity refers to the way researchers have engaged in critical discussions about research findings with project participants.

Design, as well, is now starting to consider the importance of measuring long-term impact and legacy when developing transformation projects. As an example, DOTT072 has been evaluated in terms of social, economic and educational legacy on the territory (Wood Holmes Group, 2008). On the social aspects, they considered the actual impact of DOTT projects on quality of life (outcome validity), the engagement of disadvantaged communities, the overall level of project participation (democratic and process validity) and any improved capacity to include citizens in processes of service innovation. On the educational side, the focus was on providing inspiring educational initiatives, in particular for young people, and to increase awareness of design capacity and skills (catalytic validity). No particular attention was given to dialogical validity as designers’ influence on data interpretation and problem solutions is still mostly unquestioned.

Final Considerations

Service designers work increasingly across organisations and communities to enhance transformational processes. Contributing to society transformative aims is extremely valuable, but it also carries with it a huge responsibility. Service design has been attracting, since its onset, enthusiastic young generations of practitioners and researchers that see in designing for services, particularly for the public sector, a more meaningful way to apply their skills and profession. As this societal transformative aim is now becoming increasingly explicit, designers need to become more reflexive as for what concerns their work and interventions. This article compared a selection of literature on the reform of public services with studies on participatory design, organisational development and community action research. Seven key qualifying principles were identified which described the characteristics of and conditions for transformative practices. Service designers need to better understand the dynamics and qualities of transformational change, but also to reflect on designers influence within power dynamics within various kinds of communities. Design literature is generally characterised by a highly positive rhetoric on the role and impact of design in society, while a more critical approach is becoming increasingly necessary.

With different backgrounds, consumer research has been calling for a similar change in their practice as historically their work has been driven by the theoretical and substantive interests of academics. Their new call for a transformative consumer research practice focuses upon making a positive difference in consumers’ lives (Bettany & Woodruffe, 2006). A way to do this, it is suggested, relies on introducing reflexivity in their work as a way to address power and control issues in each research encounter, understanding their influence on the research and its results (Bettany & Woodruffe, 2006). Reflexivity is described as a way to reflect on the research process to support the generation of theories and knowledge, touching in this way both issues of ontology and power.

Without deepening the meaning and practice of reflexivity in the scope of this paper, the need to introduce new skills and tools for reflexive practices within projects that hold transformational aims is evident. This might include ways to consciously track and reflect on processes, conflicts, roles, design decision points, mapping multiple perspectives and exploring individual and collaborative interpretations and evaluations of design situations and outcomes. These activities could help to better understand, position, orient, justify and evaluate designers’ role within transformational processes. Adding the adjective “transformative” to “service design” requires, therefore, a reflection not only on how designers can conduct transformative processes. There must also include a reflection on which transformations we aspire to, why we do so, and most importantly, on who is benefitted.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr. Valerie Carr and Dr. Sabine Junginger for their critical support in the writing and editing of this article.

Endnotes

1 Action research is also at the basis of aforementioned transformative service research or transformative consumer research, which represents a recent effort within the wider field of consumer research to increase the work and research on consumer welfare. David Glen Mick, president of the Association for Consumer Research, defined it as the “investigations that are framed by a fundamental problem or opportunity, and that strive to respect, uphold, and improve life in relation to the myriad conditions, demands, potentialities, and effects of consumption” (2006, p. 2). Even if still framed around the concept of consumption, transformative consumer research calls for research that aims at consumer empowerment and that therefore requires fundamentally different approaches and principles.

2 Dott07 (Designs of the time 2007) is a national initiative of the Design Council and the regional development agency One NorthEast. Dott07 is the first in a 10-year programme of biennial events developed by the Design Council that will take place across the UK. Dott07, a year of community projects, events and exhibitions based in North East England, explored what life in a sustainable region could be like – and how design could help us get there (www.dott07.com).

References

- Almega. (2008). Innovativa tjänsteföretag oc forskarsamhället: Omaka par eller perfect match. Retrieved July 5, 2011, from http://www.s-m-i.net/pdf/Innovativa%20tjansteforetag.pdf

- Anderson, W., Florin, D., Gillam, S., & Mountford, L. (2002). Every voice counts. Involving patients and the public in primary care. London: Kings Fund.

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 35(4), 216-224.

- Attree, P., & French, B. (2007). Testing theories of change associated with community engagement in health improvement and health inequalities reduction. Retrieved October 10, 2010, from p.attree@lancaster.ac.uk

- Bate, P., & Robert, G. (2007a). Toward more user-centric OD: Lessons from the field of experience-based design and a case study. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 43(42), 41-66.

- Bate, P., & Robert, G. (2007b). Bringing user experience to health care improvement: The concepts, methods and practices of experience-based design. Oxford: Radcliffe.

- Bauld, L., Judge, K., Barnes, M., Benzeval, M., & Sullivan, H. (2005). Promoting social change: The experience of health action zones in England. Journal of Social Policy, 34(3), 427-445.

- Bentley, T., & Wilsdon, J. (2003). The adaptive state, London: Demos.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. New York: Anchor Books .

- Bettany, S. M., & Woodruffe-Burton, H. W., (2006). Steps towards transformative consumer research practice: A taxonomy of possible reflexivities. Advances in Consumer Research, 33(1), 227-234 .

- Blumenthal, D. S., & Yancey, E. (2004). Community-based research: An introduction. In D. S. Blumenthal & R. J. DiClemente (Eds.), Community-based health research (pp. 3-24). New York: Springer.

- Bradwell, P., & Marr, S. (2008). Making the most of collaboration: An international survey of public service co-design. London: Demos.

- Buchanan, R. (2004). Management and design. Interaction pathways in organizational life. In R. J. Boland & F. Collopy (Eds.), Managing as designing (Chap. 4). Stanford, CA: Stanford Business Books.

- Burns, C., Cottam, H., Vanstone, C., & Winhall, J. (2006). RED paper 02: Transformation design. London: Design Council.

- Chapman, J. (2002). A framework for transformational change in organisations. Leadership & Organisation Development Journal, 23(1), 16-25.

- Chin, R., & Benne, K. D. (2005). General strategies for effecting changes in human systems. In W. L. French, C. Bell, & R. A. Zawacki (Eds.), Organization development and transformation (6th ed., pp. 40-62). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Cornwall, A. (2008). Democratising engagement what the UK can learn from international experience. London: Demos.

- Cottam, H., & Leadbeater, C. (2004). RED paper 01: Health: Co-creating services. London: Design Council.

- Department of Health. (2005). Creating a patient-led NHS – Delivering NHS improvement plan. London: Department of Health.

- Department of Health. (2008a). Real involvement. Working with people to improve health services. London: Department of Health.

- Department of Health. (2008b). High quality care for all. NHS next stage review final report. London: Department of Health.

- Ehn, P. (2008). Participation in design things. In Proceedings of the 10th Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design (pp. 92-101). New York: ACM.

- Elden, M., & Levin, M. (2001). Cogenerative learning: Bringing participation into action research. In W. F. White (Ed.), Participatory action research (pp. 127-142). London: SAGE.

- European Commission. (2009). Challenges for EU support to innovation in services - Fostering new markets and jobs through innovation (SEC-1195). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Freire, K., & Sangiorgi, D. (2010, December 3). Service design and healthcare innovation: From consumption to coproduction and co-creation. Paper presented at the 2nd Nordic Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation, Linköping, Sweden. Retrieved July 5, 2011, from http://www.servdes.org/pdf/freire-sangiorgi.pdf

- French, W. L., Bell, C. H., & Zawacki, R. A. (Eds.). (2005). Organization development and transformation (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Golembiewsky, R. T., Billingsley, K., & Yeager, S. (1976). Measuring change and persistence in human affairs: Types of change generated by OD designs. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 12(2), 133-157.

- Horne, M., & Shirley, T. (2009). Co-production in public services: A new partnership with citizens. London: Cabinet Office.

- Hosking, D. M. (1999). Social construction as process: Some new possibilities for research and development. Concepts & Transformations, 4(2), 117-132.

- Howells, J. (2007). Fostering innovation in services. Manchester, UK: Manchester Institute of Innovation Research.

- Kent County Council. (2007). The social innovation lab for Kent- Starting with people. Retrieved June 20, 2010, from http://socialinnovation.typepad.com

- Kimbell, L. (2009). The turn to service design. In J. Gulier & L. Moor (Eds.). Design and creativity: Policy, management and practice (pp.157-173). Oxford: Berg.

- Jégou, F., & Manzini, E. (Eds.). (2008). Collaborative services. Social innovation and design for sustainability. Milano: Edizioni Polidesign.

- Junginger, S. (2006). Organizational change through human-centered product development. Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Mellon University.

- Junginger, S. (2008). Product development as a vehicle for organizational change. Design Issues, 24(1), 26-35.

- Junginger, S., & Sangiorgi, D. (2009). Service design and organisational change. Bridging the gap between rigour and relevance. In Proceedings of the 3rd IASDR Conference on Design Research (pp. 4339-4348), Seoul, South Korea: Korean Society of Design Science.

- Levy, A. (1986). Second-order planned change: Definition and conceptualisation. Organizational dynamics, 15(1), 5-20.

- Manzini, E. (2008). Collaborative organisations and enabling solutions. Social innovation and design for sustainability. In F. Jegou & E. Manzini (Eds.), Collaborative services. Social innovation and design for sustainability (pp. 29-41). Milano: Edizioni Polidesign.

- Manzini, E., & Jegou F. (2003). Sustainable everyday: Scenarios of urban life. Milano: Edizioni Ambiente.

- Marmot, M. G. (2004). Tackling health inequalities since the Acheson inquiry. Journal of Epidemiology and Health, 58(4), 262-263.

- Meroni, A. (Ed.). (2007). Creative communities. People inventing sustainable ways of living. Milano: Edizioni Polidesign.

- Meroni, A. (2008). Strategic design to take care of the territory. Networking creative communities to link people and places in a scenario of sustainable development. Keynote presented at the P&D Design 2008- 8º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design, Campus Santo Amaro, San Paolo, Brazil.

- Meroni, A., & Sangiorgi, D. (2011). Design for services. Aldershot, UK: Gower.

- Mick, D. G. (2006). Meaning and mattering through transformative consumer research. Advances in Consumer Research, 33(1), 1-4.

- Miles, I. (2001). Services innovation: A reconfiguration of innovation studies. Manchester, UK: University of Manchester.

- Milton, K. (2007). Shape: Services having all people engaged- A methodology for people-centred service innovation. London: Engine Service Design.

- Ostrom, A. L., Bitner, M. J., Brown, S. W., Burkhard, K. A., Goul, M., Smith-Daniels, V., Demirkan, H., & Rabinovich, E. (2010). Moving forward and making a difference: Research priorities for the science of service. Journal of Service Research, 13(1), 4-36.

- Ozanne, J. L., & Saatcioglu, B. (2008). Participatory action research. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 423-39.

- Ozanne, J. L., & Anderson, L. (2010). Community action research. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 29(1), 123-137.

- Parker, S., & Heapy, J. (2006). The journey to the interface. How public service design can connect users to reform. London: Demos.

- Parker, S., & Parker S. (2007). Unlocking innovation. Why citizens hold the key to public service reform. London: Demos.

- Popay, J. (2006) Community engagement and community development and health improvement: A background paper for NICE. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

- Reason, P. E., & Bradbury, H. (Eds.). (2001). Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. London: Sage.

- Sangiorgi, D. (2004). Il Design dei servizi come Design dei Sistemi di Attività. La Teoria dell’Attività applicata alla progettazione dei servizi [Service design as the design of activity systems. Activity theory applied to the design for services]. Milano: Politecnico di Milano.

- Sangiorgi, D. (2009). Building a framework for service design research. In Proceedings of the 8th European Academy of Design International Conference (pp. 415-420), Aberdeen, Scotland: Robert Gordon University.

- Sangiorgi, D., & Villari B. (2006). Community based services for elderly people. Designing platforms for action and socialisation. Paper presented at the International Congress on Gerontology, Live Forever, Lisbon, Portugal.

- Senge, P., & Schamer, O. (2001). Community action research: Learning as a community of practitioners, consultants and researchers. In P. E. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research (pp. 238-249). London: Sage.

- Shuler, D., & Namioka, A. (Eds.). (1993). Participatory design: Principles and practices. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Skidmore, P., & Craig, J. (2005). Start with people: How community organisations put citizens in the driving seat. London: Demos.

- Smith, K. K. (1982). Philosophical problems in thinking about organisational change. In P. S. Goodman (Ed.), Change in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Tan, L., & Szebeko, D. (2009). Co-designing for dementia: The Alzheimer 100 project. Australasian Medical Journal, 1(12), 185-198.

- Ezell, S., Ogilvie, T., & Rae, J. (2007). Seizing the white space: Innovative service concepts in the United States. Helsinki: Tekes.

- Thackara, J. (2007). Wouldn’t be great if … London: Design Council.

- Thomas, E. (Ed.). (2008). Innovation by design in public services. London: Solace Foundation Imprint.

- Watzlawick, P., Weakland, J. H., & Fisch, R. (1974). Change: Principles of problem formation and problem resolution. New York: Norton.

- White, S. (1996). Depoliticising development: The uses and abuses of participation. Development in Practice, 6(1), 6-15.

- Winhall, J. (2004). Design notes on open health. London: Design Council.

- Wood Holmes Group. (2008). Evaluation of design of the times (Dott 07 Report). London: Design Council.

- Zeithamal, A., Parasuraman, A., & Berry, L. (1985). Problems and strategies in services marketing. Journal of Marketing, 49(2), 33-46.