Designing for Service as One Way of Designing Services

Lucy Kimbell

Saïd Business School, University of Oxford, UK

This paper considers different ways of approaching service design, exploring what professional designers who say they design services are doing. First it reviews literature in the design and management fields, including marketing and operations. The paper proposes a framework that clarifies key tensions shaping the understanding of service design. It then presents an ethnographic study of three firms of professional service designers and details their work in three case studies. The paper reports four findings. The designers approached services as entities that are both social and material. The designers in the study saw service as relational and temporal and thought of value as created in practice. They approached designing a service through a constructivist enquiry in which they sought to understand the experiences of stakeholders and they tried to involve managers in this activity. The paper proposes describing designing for service as a particular kind of service design. Designing for service is seen as an exploratory process that aims to create new kinds of value relation between diverse actors within a socio-material configuration. This has implications for existing ways of understanding design and for research, practice and teaching.

Keywords - Designing for Service, Service Design, Service Management.

Relevance to Design Practice - Helps designers identify which concepts of design and service are mobilized in projects. Describes designing for service as an exploratory process in which distinctions between products and services are not important. Instead, services are understood as socio-material configurations involving people, processes, technologies and many different kinds of object.

Citation: Lucy Kimbell (2011). Designing for service as one way of designing services. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 41-52.

Received November 29, 2010; Accepted April 30, 2011; Published August 15, 2011.

Copyright: © 2011 Kimbell. Copyright for this article is retained by the author, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

Corresponding Author: lucy.kimbell@sbs.ox.ac.uk

Lucy Kimbell is a researcher, educator and designer. She is associate fellow at Saïd Business School, University of Oxford, where she has taught an MBA elective in design and design management since 2005. In her consultancy, she works on public and commercial service design. Lucy originally studied B. Engineering Design and Appropriate Technology at the University of Warwick, then a MA. Computing in Art and Design at Middlesex University. She is completing a doctorate on design theory at Lancaster University. Her artwork has been exhibited internationally including in Making Things Public (2005) and at TEDGlobal (2011).

Introduction

Over the past decade, a profession of service designers has emerged and an interdisciplinary field of service design research has begun to take shape. Accounts of service design vary from those that see it as a new field of design to those that stress its origins in other disciplines and make references to existing approaches within design, management and the social sciences. Although these studies provide useful insights, they do not offer a systematic analysis of what is involved in designing services that draws extensively on both design and service literatures (Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011). Similarly, although the services marketing and operations management fields have discussed service design, there has been little effort to engage with different theories of design (Menor, Tatikonda & Sampson, 2002; Tax & Stuart, 1997). This reflects a deep-rooted lack of attention to design within management and organization studies resulting in part from a gulf between the research and education traditions in the social sciences and design disciplines (Boland & Collopy, 2004; Jelinek, Romme & Boland, 2008; Simon, 1969).

There is relatively little literature analyzing the work of professional service designers. Two decades ago, services researcher Evert Gummesson declared “We have yet to hear of service designers” (Grönroos, 1990, p. 57). Now, a profession of service designers exists. Many service designers are educated within the art-school design tradition within fields such as product or interaction design, rather than within the paradigm of engineering design. Although the field of service design is small and fragmented, without strong professional bodies or a developed research literature, it is visible through conferences within universities (such as the 2006 conference in Northumbria University, see http://www.cfdr.co.uk/isdn/), a professional Service Design Network (Mager, 2004) with annual conferences, books (Hollins & Shinkins, 2006; Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011), and through the work its practitioners publish in reports and on websites. There has been description of the methods and tools these designers use, but relatively little theory-building (Sangiorgi, 2009). Meanwhile, there is little published about these designers within the management literature. Exceptions include Bate and Robert’s (2007) study of what they call “experience-based” design, based on UK design consultancy ThinkPublic’s work with a cancer treatment service; Zomerdijk and Voss’s (2010) work on the design of cruises and entertainment services; and qualitative research on the material practices of service designers by Stigliani and Fayard (2010).

This paper uses an interdisciplinary approach to explore different ways of thinking about service design. It investigates whether professionals who take service design as their specialism bring something new to existing understandings of design. First, I review the literature on design and services drawing on design studies and management, especially marketing and operations. Then, I develop a framework to support discussion of service design that makes explicit underlying tensions in how the concepts of design and service are understood. Then, I illustrate in detail one quadrant of the framework through an exploratory study of three professional service design consultancies. Using an ethnographic approach, I analyze the practitioners’ activities in three cases to bring to attention the thought-worlds of the designers and the managers they worked with. Four findings provide evidence of how these practitioners approach designing services. Two are concerned with what services are: they were approached as socio-material configurations that are relational and temporal as value is constituted in practice. Two are concerned with how to do service design: designing a service was approached through a constructivist enquiry in which the designers sought to understand the experiences of diverse stakeholders and involve managers in this activity. I then reflect on the framework in the light of the ethnographic study.

This paper adds to the literature by proposing a framework that distinguishes between different approaches to service design. It explores the least understood one in depth. I describe designing for service as one specific way of approaching service design, combining an exploratory, constructivist approach to design, proposing and creating new kinds of value relation within a socio-material configuration involving diverse actors including people, technologies and artifacts. This conceptualization has implications for other design fields, since it sees service as enacted in the relations between diverse actors, rather than as a specific kind of object to be designed. The framework may be of value to practitioners and researchers by helping identify which concepts of design and service are mobilized in their work.

Literature Review

To launch this discussion I draw on several bodies of literature. Theories of design are not found in one literature. There are several design professions institutionalized in different kinds of educational and research context ranging from architecture, engineering and computing, all of which have strong professional bodies and accreditation procedures for practitioners, to graphic, product and fashion design, for example, which are often found in art schools and which have weaker institutions (Abbott, 1988). Ideas of design also permeate management, for example in organization design, often lacking a developed theory of design. Similarly, services can be approached within several management fields, including marketing, operations and information systems, influenced by different traditions within the social sciences. I draw selectively from these fields to build up a framework that distinguishes between different kinds of service design.

Design Literatures

Literature on design spans several fields including architecture (Alexander, 1971), management (Simon, 1969), engineering (Hubka, 1982), product development (Wheelwright & Clark, 1992) and systems design (Ehn & Löwgren, 1997). Descriptions of design often hinge on differences between underlying views of science and knowledge: positivist science or constructionism (Dorst & Dijkhuis, 1995). Ways of thinking of design range from attempts to build general theories to accounts of particular practices. For Alexander (1971), for example, “The ultimate object of design is form” (p. 15) whereas for Simon (1969), “Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones” (p. 55). Design can be seen as a search process for problem-solving in which the desired state of affairs is known at the outset and problems can be decomposed into smaller units before being solved (Simon, 1969), or in contrast, problem-solving is seen as a special case of design, one that is exploratory and in which the desired end state cannot yet be known (Hatchuel, 2001). Simon’s influential work is open to interpretation. For example in a close reading of Simon (1988), Pandza and Thorpe (2010) distinguish between deterministic design, in which designers’ agency is paramount as it is their decisions that determine the nature and behavior of artifacts; path-dependent design, in which adaptation and repetition determine the progress of an artifact; and path-creating or radical engineering design, in which novelty emerges through individual and collective agency. Schön (1987) saw design as a reflective practice in which professionals moved between different framings of problems as they went about solving them. Drawing on this earlier work, Buchanan (1992) described design as a liberal art capable of dealing with what Rittel and Webber (1973) call “wicked problems” for which there is no single solution and in which stakeholders play roles in defining the nature of problems. Krippendorff (2006) describes design as giving meaning to things, making design a “human-centred” activity in contrast to a technology-centred design focusing on functionality. Fry (2009) describes design as concerned with redirecting practices towards creating sustainable futures.

An important research focus is the process of designing. Design can be understood as designers co-creating problems and solutions in an exploratory, iterative process in which problems and solutions co-evolve (Cross, 2006; Dorst & Cross, 2001). Designing is seen as shaped by a situated understanding of the issue at hand (Winograd & Flores, 1986) in contrast to a view of design in which engineers design functions in response to constraints (Hubka, 1982). In recent years, some educators and practitioners have argued that designers share a kind of “design thinking” in which they frame problems and opportunities from a human-centred perspective, use visual methods to explore and generate ideas, and engage potential users and stakeholders (e.g., Brown, 2008).

Buchanan (1992) argues that designing is essentially indeterminate, but can be thought about in relation to “placements” situated around artifacts that a particular design professional makes, such as posters, products, computer systems or organizations (Buchanan, 2001). Sociologists and anthropologists have shown how specific design professionals such as engineering designers (Henderson, 1999) and product designers (Michlewski, 2008) go about their work, enriching the understanding of what designers do, but not providing generalisable accounts.

Within management, interest in design has two main strands: investigating the role of design within innovation and new product development, and thinking of management as a design science rather than a natural science. With regard to the former, design is seen as key to innovation because it involves generating new concepts and new knowledge (Hatchuel & Weil, 2009), has a structured creative process (Ulrich & Eppinger, 1995) or because design-led innovation involves firms generating new meanings for objects by engaging with a wide range of interpreters (Ravasi & Rindova, 2006; Verganti, 2009). With regard to the idea of a design science, researchers argue that management should be thought of as a design activity, although this has raised questions as to which kind of design is being invoked by these claims (Pandza & Thorpe, 2010).

A number of efforts have been made to describe the activities that go on during designing services. Many of these accounts have been written by practitioners (e.g., Burns, Cottam, Vanstone, & Winhall, 2006; Parker & Heapy, 2006). An important influence on the emerging field of service design is the idea of designing product-service systems (Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011), which has led to understanding services as socio-technical systems (Morelli, 2002). In contrast to an idea of design that focuses on designers making forms, designing services has been described as looking at services from an outside-in perspective starting with customer perspectives (Holmlid & Evenson, 2008). Service design has been seen as a subset of the field of design concerned with designing interactions with technology (Moggridge, 2006), or as having important differences to it (Holmlid, 2007).

Some of the emphasis has been on the design of the physical artifacts and encounters with service personnel that are part of a service, often called touchpoints. Researchers have explored methods to research end-users and customers and to involve them in design using ethnography and activity theory to understand their perspectives, goals and practices (Sangiorgi & Clark, 2004). Aspects of Participatory Design have been explored to examine design practitioners’ claims about co-creation, participation and emancipation during service design (Holmlid, 2009). Service design has been seen as a way to address issues of sustainability in contrast to a perceived emphasis in product and industrial design practice on creating aesthetically-pleasing novelty (Manzini, 2003) by being attentive to designing in time (Fry, 2009; Tonkinwise, 2003).

Some literature in the design field has made explicit links to management research. Pinhanez (2009) proposes thinking of services as designing customer-intensive systems emphasizing ownership and means of control in the production process. Edman (2009) explores the overlaps between design thinking and service-dominant logic (Vargo & Lusch, 2004a) and concludes that design offers tools and methods to help managers develop service-based offerings. Glushko and Tabas (2009) argue that the differences between the “back office” and “front office” orientations of different kinds of specialist are not productive; instead designers should think of back and front stages as complementary parts of a service system. Morelli (2009) discusses the tensions between the distinct origins of service design within management and engineering, and within (non-engineering) design practice and their implications for conceptualizing the field. Evenson and Dubberly (2010) describe designing for service as conceiving of, iteratively planning and constructing a service system or architecture to deliver resources that choreograph an experience that others design.

This brief review highlights key ideas in research about design, ranging from general theories of the design process and practice to accounts of particular design professions. Important tensions exist, making it difficult to generalize about design and hampering efforts to find strong foundations on which to discuss service design. A key tension exists between a deterministic view of design (Pandza & Thorpe, 2010) that sees it as a problem-solving activity that aims to work towards a desired state of affairs that can be determined in advance, or as an exploratory enquiry during which understanding of an issue or problem emerges (Dorst & Cross, 2001; Buchanan, 1992). In the latter case, a diverse group of people can be seen to be involved in constructing and interpreting the meaning of a design (Krippendorff, 2006; Verganti, 2009). The paper now turns to research in management to provide additional foundations with which to understand service design.

Management Literatures

Within management literatures, research on services is predominantly associated with marketing and operations. Underpinning this research have been efforts to define services, often in opposition to goods. However, it has proved difficult for researchers to agree what they mean by services. Four characteristics summarized by Zeithaml, Parasuraman and Berry (1985) from a survey of existing research - intangibility, heterogeneity, inseparability, and perishability - have since been shown to be not generalisable across all services and to be applicable to some goods (Lovelock & Gummesson, 2004; Vargo & Lusch, 2004b). Further developments in conceptualizing services have lead to what is currently an unresolved question. Either (a) everything is service, based on Vargo and Lusch’s (2004a; 2008a) articulation of a service-dominant logic, which draws on earlier work in services marketing and management (Grönroos, 2000; Normann, 1991; Normann & Ramírez, 1993; Ramírez, 1999), suggesting that the conventional distinction between goods and services does not matter; or (b) new ways need to be found to understand the specific qualities of organizing for and consuming services, such as highlighting ownership and access to resources (Lovelock & Gummesson, 2004). Vargo and Lusch (2004b) distinguish between service in the singular, as a fundamental activity of economic exchange, and services, in the plural, as an economic category in contrast to goods. For Vargo and Lusch, service involves dynamic processes within which value is co-created by actors within a value constellation (Normann & Ramírez, 1993) or service system (Maglio, Srinivasan, Kreulen, & Spohrer, 2006).

Despite this lack of agreement on how to define services, researchers have advanced knowledge about how organizations manage them. However, discussion about how organizations design services has not drawn in detail on design literatures and researchers have rarely made explicit links to theories of design. The design process has been seen as part of a process of new service development (Scheuing & Johnson, 1989; Zeithaml & Bitner, 2003) or the redesign of existing services (Berry & Lampo, 2000). Design is seen as a phase that comes after concept generation and testing and business analysis in contrast to definitions of design introduced above that see design as generating new concepts and new knowledge. Although operations management researchers have paid attention to the design of the service delivery system and the service process (Edvardsson & Olsson, 1996; Fitzsimmons & Fitzsimmons, 2000; Ramaswamy, 1996) or bringing modularity to service architecture (Voss & Mikkola, 2007), overall new service design and development are not well understood (Menor, Tatikonda, & Sampson, 2002). Studies of manufacturing processes such as in the car industry (Womack, Jones, & Roos, 1990) and business process engineering (Hammer & Champy, 1993) with important foci on quality, continuous improvement and benchmarking (Zairi & Sinclair, 1995) may apply to service operations. However, it is possible that experiential services might present new challenges for knowledge based in manufacturing. Recent work within information systems has led to calls for a “services science” combining engineering, management and the social sciences (Chesbrough & Spohrer, 2006). An analysis of these developments identified enhancing service design as a research priority, seeing it as a site for cross-disciplinary research (Ostrom et al., 2010).

Shostack (1982; 1984) was a pioneering advocate of the idea that services could be designed intentionally, proposing that documenting and monitoring the service delivery process was the key methodology behind designing a successful service offering. Shostack proposed creating a visual representation that she called a “blueprint” of a service design. She argued this was an important way to specify what a service ought to be like. A blueprint represents what happens in front of the customer engaging with service personnel and service “evidence”, and behind a “line of visibility” where others supported service delivery.

Complementing this emphasis on managing the service process, researchers in service marketing point to the importance of the service encounter, understood as a person-to-person interaction (Solomon, Surprenant, Czepiel, & Gutman, 1985) or an interaction between customers and human and artefactual service evidence (Bitner, Boons, & Tetreault, 1990). Parasuraman, Zeithaml and Berry (1985) developed ways to study service quality. The service encounter creates a “moment of truth” at the interface of service providers and their customers (Normann, 1991). Alam and Perry (2002) emphasize a customer-orientation in new service development. Berry, Wall, and Carbone (2006) argue for the importance of designing service “clues” when “engineering” service experiences. Carbone and Haeckel (1994) claim that paying greater attention to the details of the material artifacts involved in a service experience will result in greater customer satisfaction. Further extending the understanding of what is involved in constituting a service, Bitner (1992) argues that what she calls “servicescapes” – the physical surroundings in which service is provided and experienced – play an important role in determining the perceived quality of consumer services. Hence Stuart and Tax (2004) draw on theatre as an approach to designing memorable service experiences.

Efforts to bridge the gaps between marketing and operations perspectives on service design include developing service concepts (Goldstein, Johnston, Duffy, & Rao, 2002) and a proposal to create a new function called customer experience management, responsible for ensuring that organizational service delivery aligns with marketing promises and customer expectations (Kwortnik & Thompson, 2009). Others have taken forward Shostack’s work on blueprints and shown how creating experience blueprints helps design multi-interface services delivered using different channels and technologies (Patricio, Fisk, & Cunha, 2008) and how such activities help multi-functional teams generate opportunities for innovation (Bitner, Ostrom, & Morgan, 2008).

Recent empirical work that studies professional designers’ approach to designing services includes Bate and Robert’s (2007) study of designers using an ethnographic approach to understanding users’ experiences in their own terms and involving them in co-designing cancer services. Voss and Zomerdijk (2007) study professionals involved in designing experiential services such as travel and entertainment. They find that these professionals approached design from the perspective of the customer journey, resembling Shostack’s blueprints, and that these designers have relatively informal methodologies shaping how they design. Blomberg (2008) illustrates the importance of focusing on how proposed service users negotiate the meaning of a service. Zomerdijk and Voss (2010) develop six propositions about the design of experiential services and test them empirically in 17 case studies, which highlight the importance of context in designing service experiences. Holopainen (2010) finds that the emerging concept of service design is extended to cover almost entirely the development of new services.

Together, these concepts – the design of the service delivery system, continuously designing processes to improve quality, the service encounter, blueprints, evidence, clues, serviscapes and the management of customer experiences – represent importance advances in understanding how organizations design services, although lacking clarity about what is meant by design. There has been research into how professional designers who see their work as service design go about doing it, but further work is needed. It remains unclear at a conceptual level if the distinction between goods and services is important and how designing for service might be approached if, as Vargo and Lusch (2004a) suggest, service is understood as dynamic processes within which value is co-created.

Different Ways of Approaching Service Design

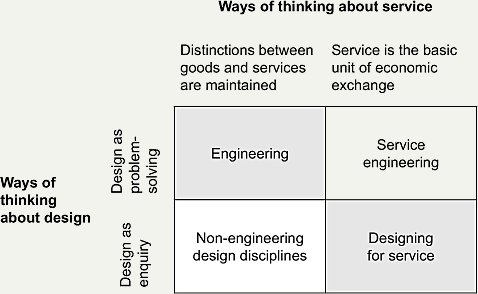

This review identifies that two areas in which we might expect to find research on service design – within design literature and within services literature – have not produced a developed body of knowledge. Rather, what emerges are two important tensions. The first is between understanding design either as problem-solving that aims to realize what has already been conceived of, or as an exploratory enquiry involving constructing understanding about what is being designed, involving end users and others in creating meaning. The second is a tension between the view that the distinction between goods and services matters significantly, or that service is better understood as a fundamental activity with multiple actors within a value constellation. Figure 1 summarizes these perspectives.

Figure 1. Approaches to conceptualizing service design.

The framework in Figure 11 has two axes: one concerns how service is understood, the other concerns the nature of design. Together, the quadrants propose distinct ways of understanding service design. In the top left quadrant, design is seen as problem-solving and the conventional distinction between goods and services is maintained, a view that underpins work in some management fields (e.g., Shostack, 1982; Ulrich & Eppinger, 1995). This quadrant is labeled “engineering” as its focus is the design of new products and services that can be specified in advance using systematic procedures; services are one particular category of artefact to be designed. Below, design can be understood as an exploratory process of enquiry that can be applied to different kinds of artefact such as products or services and where the distinctions based in industrial manufacturing between types of designed things matter (e.g, Buchanan, 2001; Burns et al., 2006). Within this quadrant sit the conventional fields or sub-disciplines of design in the art or design school traditions, with their focus on particular kinds of artefact such as furniture design, interiors or interaction design. This quadrant is labeled “non-engineering design disciplines”.

The top right quadrant sees design as problem-solving, but views service as a fundamental process of exchange (e.g., Chesbrough & Spohrer, 2006; Kwortnik & Thompson, 2009) influenced by the service-dominant logic (Vargo & Lusch, 2004a). This quadrant is labeled “service engineering” since the emphasis is on service, but the underlying design tradition is engineering. Finally, the bottom right quadrant sees design as an exploratory enquiry, but does not make an important distinction between goods and services (e.g, Bate & Robert, 2007). This quadrant is labeled “designing for service” rather than designing services, echoing work by several practitioners and scholars in the use of the preposition “for” (cf Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011; Kimbell & Seidel, 2008). As Manzini (2011) similarly argues, talking of designing for services rather than designing services recognizes that what is being designed is not an end result, but rather a platform for action with which diverse actors will engage over time. Designing for service, rather than designing services, points to the impossibility of being able to fully imagine, plan or define any complete design for a service since new kinds of value relation are instantiated by actors engaging within a service context. Designing for service remains always incomplete (cf Garud et al, 2008).

This framework makes explicit differences in how people think about design and service, shaping how service design can be understood. It helps illuminate the underlying concepts about design and service that practitioners bring to their work as they engage in service design. The paper now turns to an empirical study of professional designers working within the exploratory design tradition. As practitioners who say they design services, the ways they approach their work will add depth to the framework.

Research Design

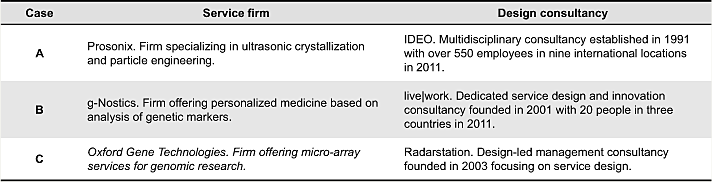

Three professional consultancies offering service design took part in the study.2 Each was paired with a small firm offering a service focusing mainly on business customers. These were small enterprises without well-established processes and routines. Each offered a service based on a novel technology or recent scientific research. I chose the firms to explore what service design might mean in a context with little previous exposure to design professions, in contrast to consumer, entertainment or hospitality sectors from which concepts in services marketing have been drawn. Exposing technology-based firms unfamiliar with service design to professionals advocating it created conditions in which the designers were likely to make efforts both to reflect on the relevance of their approach to this context and to invest resources in communicating what they were doing. The designer-firm pairs worked together for six days over five months, for which the designers were paid a fee. All the designers and managers attended five workshops over one year. Around 20 researchers from several management fields and from design also attended the workshops, which generated a multidisciplinary conversation about designing services.

Written up in three cases, the study focuses on how the designers practiced service design by describing what they did as they began their relationship with the firm they were asked to work with when the latter did not have a clear idea what service design was or what it might do for them or with them. Given an open brief to “do some service design” and with limited resources, the designers engaged with their temporary clients in similar ways although each case is written up to highlight differences between them. The cases aim to illustrate the framework in more depth by connecting the literature discussed above with fieldwork.

An ethnographic approach was taken to bring into view what the designers and managers thought was involved in doing such design work. This was done for two reasons, one theoretical and one methodological. Firstly, the theoretical underpinning to the research is theories of practice that place everyday activities as the locus for the production and reproduction of social relations (Reckwitz, 2002; Schatzki, 2001). In research into practices it is important to be able to observe what people do, the objects they create and work with, what they say and the nature of their work as they go about it (Carlile, 2002). To better understand how designers structure their work, it was important to specify the empirical practices involved in their work. Secondly, the ethnographic approach offered methodological benefits (Neyland, 2008). Observing designers as they went about their work provided better access to their thought-worlds than relying on survey data or on interviews. Data were gathered both by observing some of the encounters between the designers and the managers, and in one instance of the designers working together in the studio, and by watching video recordings of these meetings made by a third party, as well as recording on video the five project workshops. In total, I had access to 40 hours of video footage as well as my notes from my observations of the designers and the artifacts created by the designers and by workshop participants. One of the challenges has been to represent such a large collection of data in three short cases. The data were collected between December 2006 and October 2007. Analysis was shaped abductively by the multidisciplinary conversations that emerged in the workshops and by reviewing the literature (Blaikie, 2000).

Sampling

The study involved three design consultancies of different sizes and with existing clients in service design. The three firms involved were selected on the basis of being growth-phrase small enterprises offering services based on a technical or scientific innovation in which the service(s) had been designed without the benefit of working with a professional service designer. They are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Organizations involved in the study.

Case A

The project began with one designer from IDEO visiting Prosonix and meeting firstly with the CEO and later with several members of the team to find out more about their technologies and services. As a result of this discussion, the pair agreed that IDEO would help the company create an “opportunity map” for their services. This lead to another designer accompanying the manager of business development to a first meeting with a potential client to observe the discussion and description of services. The next step was a day spent at IDEO’s London studio in which both designers and the business development manager generated the opportunity map based on what the designers referred to as “insights” gathered by the designers at their meetings and further input from the manager. In this workshop, the designers provided a structured yet informal way to generate ideas including creating “what if” scenarios each focusing on particular industries within which the organization’s services could be exploited.

In this workshop, one of the designers created a sketch representing the problem facing Prosonix’s customer in which a small human figure is seen trying to push a large object up a hill. This sketch crystallized the problem facing the business manager and his role in communicating the enterprise’s service to potential client organizations. It became a motif used repeatedly in subsequent conversations and at project workshops by the manager and the designers. Another visualization used repeatedly in the project was a Venn diagram of three overlapping circles labeled desirability, feasibility and viability. It represented the consultancy’s criteria for a successful service design (Jones & Samalionis, 2008), which another colleague from the consultancy had presented at both of the first two workshops in the research project. One designer explained “Often when we’re talking about innovation or trying to get businesses to do new things we’re talking about desirability; which is what do the customers want, the human side of it and then we’ve got viability and feasibility…How can we make money out of it? And how can we make it?” The manager seemed to accept this framework as a way of organizing the decision-making during his work on scenario generation with the designers that day. In later discussions at the project workshops, both he and the CEO referred several times to these three criteria and commented that their organization paid insufficient attention to desirability. Finally, the designers and manager prioritized which scenarios to take further and agreed on the next piece of work the consultancy would undertake.

Working in their studio with a colleague, the two designers created four elements for what they called a toolkit for the company. They presented it to the business development manager at a final meeting in London. Each of these artifacts linked to the prioritized scenarios and used high production values. They included three visual artefacts the designers called “adcepts” (advertising concepts) in the form of fictional advertisements in glossy magazines, communicating to Prosonix’s potential clients the sorts of innovations possible using the company’s particle engineering services. One, aimed at potential pharmaceutical clients, showed an imaginary asthma inhaler. Another showed an imaginary perfume product and a third a fictional cosmetic product. Finally, the designers presented a prototype folder they had created to help the business development manager customize the service for existing or new clients by organizing information about them and prompting him to consider particular aspects of the service in relation to their needs. At the meeting, the manager seemed satisfied with these artifacts. There was also a discussion about how the enterprise might act on these ideas beyond the scope of the study.

Case B

Consultancy live|work began their work with two designers making a trip to the offices of g-Nostics with the aim of getting to know the organization and its service. The enterprise asked the designers to help with its Nicotest smoking cessation service then under trial in some UK pharmacies. The service supports people trying to give up smoking by using genetic testing to identify appropriate levels of nicotine replacement therapies. During their meeting with the CEO and the business development manager, the designers focused on learning about the experience of the customer using the service, while the service managers talked on a more abstract level about strategy, marketing and the industries in which they were working. One of the designers repeatedly turned the conversation back to the experience of using the service, using phrases such as “From the user’s point of view…” as he persuaded the managers to describe the service in detail. During this meeting, the designers were also attentive to the artifacts that the managers showed them and wanted to take them away. They also successfully requested permission to access the website that formed part of the service.

The designers’ second activity was visit to a pharmacy where the service was being trialled in the company of one of the enterprise managers, a cameraman and the author. Here, one of the designers conducted a walk-through of the service involving the pharmacy assistant taking blood and saliva samples from him as part of the test and conducting an online registration, as if he were a customer. During this, the designer asked the assistant to explain what was going on at each stage and her views on the service as a whole. The other designer documented this with photos, notes and drawings with a particular focus on the assistant’s work practices and what kinds of artifacts were part of the service encounter, such as the test kit, but also attending to other artifacts such as a hand-written thank you note on the wall of the small consulting room and marketing literature produced by other organizations.

Their next activity took place in the consultancy’s London studio where the two designers assembled on the wall what they called the “customer journey”, combining photographs they had taken at the pharmacy and pages from the service website, again observed by the author. Grounded in one designer’s experience of undertaking the test, this visual representation followed the would-be non-smoker as they engaged with what the designers called the service “touchpoints” over time. These ranged in material form from the graphic design of a poster in the pharmacy window to the website for customers to connect with other people trying to give up smoking. The designers appeared to go about this in a relatively unstructured way, although as they built up the customer journey, they distinguished between phases they labeled awareness, access and joining. A third colleague joined them who had attended the first two workshops in this study. Together, the designers critiqued the service, jumping repeatedly from the detail of the design of the touchpoints to the enterprise’s goals and the customer proposition. As they talked, some of them wrote on sticky notes and stuck them on the assemblage on the wall, building up a detailed, layered analysis of the customer journey for the existing service. One designer began to draw a “stakeholder ecology” diagram, which showed organizations, artifacts such as computer servers as well as people involved in constituting the service, with arrows showing links between them.

Next, the three designers sat at a table, individually sketching in response to issues they had identified in assembling the customer journey on the wall. Using the company’s own template, which included “user need” as a category to fill out, the designers quickly generated simple sketches for improvements to existing touchpoints (e.g., the test kit pack), proposals for new service components (e.g. a website targeting would-be quitters) and proposals for entirely new services (e.g. a genetic test data bank).

Later, the designers produced a digital document representing the customer journey that organized the timeline, touchpoints, issues and opportunities into phases of the service engagement. The final activity involved one of the designers visiting the enterprise again, taking their sketches, the customer journey diagram and other artifacts and talking through them around a table. This lead to a more structured conversation in relation to a poster the designer brought with them and placed on a wall. The managers’ responded very positively to the designers’ suggestions, both those at the level of improvements to an existing touchpoint as well as those proposing a new way of conceiving of the service. This lead to a discussion about how the enterprise might take forward these ideas beyond the scope of the academic study.

Case C

In their engagement with Radarstation, the OGT managers decided to focus on their custom service creating micro-arrays, enabling researchers to understand genetic information gathered from research subjects and processed by OGT. After an initial meeting at OGT’s offices in which the designers sought to understand the enterprise’s activities by meeting the COO, the designers decided they needed to know more about the enterprise’s customers, typically research managers in companies or university researchers. They conducted face-to-face interviews with one existing, one past and one new client, taking notes and photos. The designers then generated three visual representations of the customer journey, arranging in a linear sequence the touchpoints through which each client engaged with OGT over time, such as emails, phone calls and contracts.

The next stage involved the designers organizing what they referred to as a “co-creation workshop” attended by the COO and another manager. During this workshop the managers and designers first sat round a table studying the customer journeys for each client and hearing what the designers referred to as “insights” based on the interviews they had conducted. On a flipchart, one of the designers drew a two-by-two matrix with cost and value as its two axes. The COO filled this in as he discussed the firm’s positioning in relation to its competitors. The participants spent time writing and drawing on copies of the consultancy’s touchpoint template, which included sections for user need, OGT’s approach, customer benefits and alternatives. These were then assembled along a wall in the sequence of the customer journey, discussed and annotated with sticky notes.

Back in the studio, the designers further analyzed the customer journey and sketched and annotated possible solutions. As their final outputs, the designers created a generalized customer journey and a presentation that summarized much of the discussion in the co-creation workshop; it also included recommendations for ways to “realign key touchpoints”. These recommendations were driven by making the process more visible and streamlined, handholding new customers and extending OGT’s relationship with the customer. The document focused mostly on touchpoints in the service and proposed an improvement to each existing touchpoint, practices around it or made suggestions for entirely new ones. Each of these included comments about the user need, approach and benefit; some included a comment about competitors. These recommendations were presented at a project workshop and later sent to the organization by email.

Findings

Looking at the cases together, four main themes emerge, two connected with what these designers understand themselves to be designing when they are doing service design and two connected with how they go about doing it.

Firstly, these designers paid great attention to design of the material and digital touchpoints connected with the firm’s service, to people and their roles, knowledge and skills and where these service encounters took place. In contrast to an idea of service as being intangible, a key definition of service that has recently been questioned (e.g., Lovelock & Gummesson, 2004; Vargo & Lusch, 2004b), these designers’ work practices focused extensively on studying and then redesigning the artifacts they saw as part of the service and participants’ practices as they engaged with the firms. In some cases, this included studying artifacts that had not been created by the service organization (e.g., Cases A and B), suggesting that the designers have a broad view of the artifacts and interactions that constitute a service. However, while they paid attention to many artifacts within the services, the distinction between products and services did not seem important in their work. Far from being intangible, a service can be thought of as both social and material. Thus the designers seemed to conceive of service in a similar way to Vargo and Lusch (2004a), who propose that material objects (such as “goods”) play roles in constituting value-in-use, but that service is the fundamental activity of economic exchange.

Secondly, the designers in this study understood service as both relational and temporal as users and stakeholders of different kinds interacted with the service firms through practical engagement with artifacts and people over time and space. Echoing discussions about meaning within design (Krippendorff, 2006; Verganti, 2009), the designers seemed to see the value of service as constituted in practice involving a wide array of material, digital and human actors (Normann & Ramírez, 1993; Vargo & Lusch, 2008a). In their visits to the firms, conversations with managers and during their analysis of the firms’ websites and other materials, the designers repeatedly sought to understand the nature of each firm’s offering and the creation of value through the practices of end users and others such as employees, instead of attending to pre-defined categories of science, technology, product or service. During a workshop, one designer from live|work emphasized the temporality of service by describing organizations as being “in perpetual beta”, a process of ongoing change as services were repeatedly redesigned and constituted in practice. The designers tried to represent the relational and temporal nature of service in visual form, for example by creating two-dimensional documents showing touchpoints in the customer journey (e.g., all cases) or as a service ecology visualized from a bird’s eye view (e.g., Case B).

Thirdly, the designers approached their work as an enquiry in which they and others would construct an understanding of what the service was and how they might approach design or re-design. In all three cases, they were involved in considering existing services in operation that had been assembled by the firm without the help of specialist service designers. All the designers invested the limited resources available to them in this study in trying to understand the service from the point of view of customers and end users, as well as the service organization’s perspectives, accessed by interviewing managers. This emerging understanding shaped how they went about their work. In the documents they created such as visual representations of their design processes and during their presentations at the workshops, they emphasized an iterative process during which they conducted their research, developed insights and generated ideas through sketching or prototyping to be assessed by the firm. In Cases A and B, they also generated entirely new service concepts that did not draw directly on knowledge about existing customers and users (Verganti, 2009). In contrast to descriptions of the new service development process in which design is a phase (Scheuing & Johnson, 1989), these designers saw their entire activity as design, consistent with Holopainen (2010).

Fourthly, the designers created opportunities for the managers of the firms they worked with to take part in this enquiry and invested resources in creating material artifacts and situations that enabled this. Rather than mostly working on their own and presenting a final deliverable to the firm, these consultants spent time and effort to organize and facilitate workshops with the managers they worked with. The designers described how they preferred to include end users and customers in such workshops when resources allowed. These activities suggest a view of service design as a constructive process involving both professional designers and managers, but also other stakeholders such as present or past customers and service personnel. The designers made an important part of their work the construction of artifacts to make visible and comprehensible the complexities of the service, ranging from prototypes (Case A) to sketches (Cases A and B) to the customer journey diagrams (all three). These boundary objects (Star & Griesemer, 1989; Carlile, 2002) played an important role in all three cases as the designers tried to make the practices of service stakeholders visible to the managers to help with decision-making about the redesign of the services. This finding is consistent with Stigliani and Fayard (2010).

Discussion

This paper has explored different ways of understanding service design. Secondly, it has considered what we can learn from professional designers who say they practice it. The framework in Figure 1 identified important differences in the literatures on design and on service on to which it is possible to map different professional and disciplinary emphases as to how design and service are understood. The findings from the three cases draw attention to two aspects of service design – what is being designed in the design of services and how designers go about service design.

The research found that the designers attended closely to a wide range of material and digital artifacts and practices within services. For these designers, a service is both social and material. They saw service as relational and temporal as value was created in practice. In addition, the research showed that these designers approached designing as an open-ended enquiry in which part of their work involved creating boundary objects that served to make visible these actors within a service, as both they and the managers constructed an understanding of the service. Combining these suggests that what these professional service designers are doing is focused on the bottom right quadrant in Figure 1: they are designing for service. The analysis of the cases suggests they combine a constructivist approach to doing design, with a view that the distinction between goods and services is not important. Rather, the designers’ efforts to understand the strategies of the businesses they worked with and to rethink these highlighted how they saw service as relational and instantiated in practice. In their research and proposals to redesign aspects of the enterprises’ services, the designers focused on how the various actors involved in the service were configured to create value.

By referring to this as designing for service, rather than service design, makes clear that the purpose of the designers’ enquiry is to create and develop proposals for new kinds of value relation within a socio-material world. The paper’s contribution is to describe a distinctive way of approaching service design, that is, design for service, which has not thus far been presented in either the design or management literatures.

I now turn to the possible implications of this research for managers, designers and researchers. The framework makes a distinction between different ways of thinking about service design and may help designers and managers navigate the complexities they face in organizations, whether working as consultants or in-house and whatever their originating discipline. The designers in this study attended to practices and value relations involving artefacts as diverse as posters, websites and staff training manuals, suggesting that designing for service is a strategic kind of design activity that operates at the level of socio-material configurations or systems, rather than being framed within pre-existing design disciplines. Some literature on service design sees it as a new sub-discipline of design (Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011). However, this study suggests that designing for service offers an opportunity to rethink professional design and its role in organizations and societies more broadly by making clear how underlying concepts such as service are mobilized. Evenson and Dubberly (2010) and Manzini (2011) also make this argument. For researchers, the diversity of research used in this paper, from design studies to operations, marketing and practice theory, offers a new perspective on service design that joins up literatures at a time when calls for interdisciplinary research approaches have been made.

Finally, a discussion of the limitations of this study is required. The framework in Figure 1 connects important conceptual and empirical research in design and management fields. However, the use of a 2x2 matrix simplifies and reduces any such wide range of contributions. Secondly, the fieldwork focused on only one quadrant of the framework. It helps clarify what is distinctive about the approach of self-titled service designers, but further work is needed to test the framework’s relevance by exploring in depth the other three quadrants. Thirdly, in this study the use of an ethnographic approach to generating data for cases was appropriate for an exploratory study in which the phenomenon is not well understood, but this limits how these findings might be generalized. Fourthly, the study focused on service designers working for technology-based small enterprises. This may have produced findings that are not generalizable to other contexts such as those in which notions of customer experience are more common. Finally, there was no attempt to assess whether the approach practiced by these designers would lead to better designed services. The emphasis was on describing the approach. Further work is needed to assess its effectiveness.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to explore how the work of service design is understood. It developed a framework through which service design can be discussed and explored it by analyzing the work of designers who say they design services. Two approaches have been combined: an examination of literatures in design and management fields and an exploratory study of three design consultancies specializing in service design. In doing so, the paper has highlighted different ways of thinking about service design. In design, I noted a distinction between seeing design as problem-solving in which the desired state of affairs is already known or as a process of enquiry during which meaning is constructed with diverse stakeholders. Within research on services, I highlighted contrasting positions that either see important distinctions between the ways goods and services are designed and managed or which see the distinction as not important, but which instead sees service as the fundamental basis of creating value. From three cases, I presented four findings that add depth to one quadrant of this framework. Using the theoretical perspective of practices helped focus the research on the thought-worlds of the designers showing how they enact service design in their day-to-day work. By combining the literature and findings, I add depth to one specific way of thinking about service design. I called this approach designing for service and argued it is rooted in a constructivist approach to design in which designers and diverse others are involved in an ongoing enquiry and in an understanding of service that does not rest on the distinction between goods and services from industrial manufacturing, but rather sees service as the fundamental basis of exchanges of value.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and Engineering and Physical Science Research Council’s Designing for the 21st Century scheme. The paper was improved with input from the editors and anonymous reviewers and also Antti Ainamo, Kate Blackmon, Rachel Cooper, George Julian, Steve New, Rafael Ramírez, Daniela Sangiorgi and Bruce Tether.

Endnotes

1 Like any framework this one reduces the diversity of literature in the field, such as different ways of characterizing different design fields such as engineering design or product design.

2 This is the first comprehensive report on this research, part of which has been described in Kimbell (2009) and Kimbell and Seidel (Eds.) (2008).

References

- Abbott, A. (1988). The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Alam, I., & Perry, C. (2002). A customer-oriented new service development process. Journal of Services Marketing, 16(6), 515-534.

- Alexander, C. (1971). Notes on the synthesis of form. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bate, P., & Robert, G. (2007). Bringing user experience to healthcare improvement: The concepts, methods and practices of experience based design. Oxford: Radcliffe.

- Berry, L. L., & Lampo, S. K. (2000). Teaching an old service new tricks: The promise of service redesign. Journal of Service Research, 2(3), 265-275.

- Berry, L. L., Wall, E. A., & Carbone, L. P. (2006). Service clues and customer assessment of the service experience: Lessons from marketing. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(2), 43-57.

- Bitner, M. J., Ostrom, A., & Morgan, F. (2008). Service blueprinting: A practical technique for service innovation. California Management Review, 50(3), 66-94

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57-71.

- Bitner, M. J., Boons, B. H., & Tetreault, M. S. (1990). The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 71-84.

- Blaikie, N. (2000.) Designing social research: The logic of anticipation. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

- Blomberg, J. (2008). Negotiating meaning of shared information in service system encounters. European Management Journal, 26(4), 213-222.

- Boland, R., & Collopy, F. (Eds.) (2004). Managing as designing. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford.

- Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard Business Review, 86(6), 84-92.

- Burns, C., Cottam, H., Vanstone, C., & Winhall, J. (2006). RED paper 02: Transformation design. London: Design Council.

- Buchanan, R. (1992). Wicked problems in design thinking. Design Issues, 8(2), 5-21.

- Buchanan, R. (2001). Design research and the new learning. Design Issues. 17(4), 3-23.

- Carbone, L. P., & Haeckel, S. H. (1994). Engineering customer experiences. Marketing Management, 3(3) 8-19.

- Carlile, P. R. (2002). A pragmatic view of knowledge and boundaries: Boundary objects in new product development. Organization Science, 13(4), 442-455.

- Chesbrough, H., & Spohrer, J. (2006). A research manifesto for services science. Communications of the ACM, 49(7), 35-40.

- Cross, N. (2006). Designerly ways of knowing. Berlin: Springer.

- Dorst, K., & Dijkhuis, J. (1995). Comparing paradigms for describing design activity. Design Studies, 16(2), 261-274.

- Dorst, K., & Cross, N. (2001). Creativity in the design process: Co-evolution of problem-solution. Design Studies, 22(5), 425–437.

- Dunne, D., & Martin, R. (2006). Design thinking and how it will change management education: An interview and discussion. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 5(4), 512-523.

- Ehn, P., & Löwgren, J. (1997). Design for quality-in-use: Human-computer interaction meets systems development. In M. Helander, T. K. Landauer, & P. V. Prabhu (Eds.), Handbook of human-computer interaction (2th ed., pp. 299-313). New York: Elsevier.

- Edman, K. W. (2009, November) Exploring overlaps and differences in service-dominant logic and design thinking. Paper presented at the 1st Nordic Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation, Oslo, Norway.

- Edvardsson, B., & Olsson, J. (1996). Key concepts for new service development. The Service Industries Journal, 16(2), 140-164.

- Evenson, S., & Dubberly, H. (2010). Designing for service: Creating an experience advantage. In G. Salvendy & W. Karwowski (Eds.), Introduction to service engineering (pp. 403-413). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Fitzsimmons, J., & Fitzsimmons, M. (2000). New service development: Creating memorable experiences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Fry, T. (2009). Design futuring: Sustainability, ethics and new practice. Oxford: Berg.

- Garud, R., Jain, S., & Tuertscher, P. (2008). Incomplete by design and designing for incompleteness. Organization Studies, 29(3), 351-371.

- Glushko, R., & Tabas, L. (2009). Designing service systems by bridging the “front stage” and “back stage”. Information Systems E-Business Management, 7(4), 407-427.

- Goldstein, S. M., Johnston, R., Duffy, J., & Rao, J. (2002). The service concept: The missing link in service design research? Journal of Operations Management, 20(2), 121-134.

- Grönroos, C. (2000). Service management and marketing: A customer relationship approach (2nd ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Hammer, M., & Champy, J. (1990). Reengineering the corporation: A manifesto for business revolution. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Hatchuel, A. (2001). Towards design theory and expandable rationality: The unfinished programme of Herbert Simon. Journal of Management and Governance, 5(3-4), 260-273.

- Hatchuel, A. and Weil, B. (2009). C-K theory: An advanced formulation. Research in Engineering Design, 19(4), 181-192.

- Henderson, K., (1999). On line and on paper: Visual representations, visual culture, and computer graphics in design engineering. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Hollins, B., & Shinkins, S. (2006). Managing service operations: Design and implementation. London: Sage.

- Holmlid, S. (2007, May 29). Interaction design and service design: Expanding a comparison of design disciplines. Paper presented at the 2nd Nordic Design Research Design Conference, Stockholm, Sweden. Retrieved October 11, 2009, from http://ocs.sfu.ca/nordes/index.php/nordes/2007/paper/view/140/95

- Holmlid, S. (2009, November 26). Participative, co-operative, emancipatory: From participatory design to service design. Paper presented at the 1st Nordic Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation, Oslo, Norway. Retrieved July 5, 2011, from http://www.aho.no/PageFiles/6819/New/Holmlid%20Participative,%20co-operative,%20emancipatory.pdf

- Holmlid, S., & Evenson, S. (2008). Bringing service design to service sciences, management and engineering. In B. Hefley & W. Murphy (Eds.), Service science, management and engineering: Education for the 21st century (pp. 341-345). Berlin: Springer Verlag.

- Holopainen, M. (2010). Exploring service design in the context of architecture. The Service Industries Journal, 30(4), 597-608.

- Hubka, V. (1982). Principles of engineering design. Guildford, UK: Butterworth.

- Kimbell, L. (2009). The turn to service design. In G. Julier & L. Moor (Eds.), Design and creativity: Policy, management and practice (pp. 157-173). Oxford: Berg.

- Kimbell, L., & Seidel, V. (Eds.) (2008). Designing for services – Multidisciplinary perspectives. Proceedings from the exploratory project on designing for services in science and technology-based enterprises. Oxford: Saïd Business School.

- Kwortnik, R. J., & Thompson, G. M. (2009). Unifying service marketing and operations with service experience management. Journal of Service Research, 11(4), 389-406

- Jelinek, M., Romme, A. G. L., & Boland, R. J. (2008). Introduction to the special issue: Organization studies as a science for design: Creating collaborative artifacts and research. Organization Studies, 29(3), 317-329.

- Krippendorff, K. (2006). The semantic turn: A new foundation for design. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis.

- Kwortnik, R. J. Jr., & Thompson, G. M. (2009). Unifying service marketing and operations with service experience management. Journal of Service Research, 11(4), 389-406.

- Lovelock, C., & Gummesson, E. (2004). Whither services marketing? In search of a new paradigm and fresh perspectives. Journal of Service Research, 7(1), 20-41.

- Mager, B. (2004). Service design: A review. Koln: Koln International School of Design.

- Maglio, P. P., Srinivasan, S., Kreulen, J. T., & Spohrer, J. (2006). Service systems, service scientists, SSME, and innovation. Communications of the ACM, 49(7), 81-85.

- Manzini, E. (2003). Scenarios of sustainable wellbeing. Design Philosophy Papers, 1. Retrieved November 24, 2009, from http://www.desphilosophy.com/

- Manzini, E. (2011). Introduction. In A. Meroni & D. Sangiorgi (Eds.), Design for services (pp.1-6). Aldershot, UK: Gower Publishing.

- Menor, L. J., Tatikonda, M. V., & Sampson, S. E. (2002). New service development: Areas for exploitation and exploration. Journal of Operations Management, 20(2). 135-157.

- Meroni, A., & Sangiorgi, D. (2011). A new discipline. In A. Meroni & D. Sangiorgi (Eds.), Design for services (pp. 9-33). Aldershot, UK: Gower Publishing.

- Michlewski, K. (2008). Uncovering design attitude: Inside the culture of designers. Organization Studies, 29(3), 373-392.

- Moggridge, B. (2006). Designing interactions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Morelli, N. (2002). Designing product/service systems: A methodological exploration. Design Issues, 18(3), 3-17.

- Morelli, N. (2009, November 24). Beyond the experience: In search of an operative paradigm for the industrialization of services. Paper presented at the 1st Nordic Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation, Oslo, Norway. Retrieved November 21, 2009, from http://www.aho.no/PageFiles/6819/Morelli%20%20Beyond%20the%20experience.pdf

- Neyland, D. (2008). Organizational ethnography. London: Sage.

- Normann, R. & Ramírez, R. (1993). Designing interactive strategy: From value chain to value constellation. Harvard Business Review, 71(4), 65-77.

- Normann, R. (1991). Service management: Strategy and leadership in service business. Chichester, NY: Wiley.

- Ostrom, A. L., Bitner, M. J., Brown, S. W., Burkhard, K. A., Goul, M., Smith-Daniels, V., Demirkan, H., & Rabinovich, E. (2010). Moving forward and making a difference: Research priorities for the science of service. Journal of Service Research, 13(1), 4-36.

- Pandza, K., & Thorpe, R. (2010). Management as design, but what kind of design? An appraisal of the design science analogy for management. British Journal of Management, 21(1), 171-186.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 49(4), 41-50.

- Parker, S., & Heapy, J. (2006). The journey to the interface: How public service design can connect users to reform. London: Demos.

- Patricio, L, Fisk, R. P., & Cunha, J. F. (2008). Designing multi-interface service experiences: The service experience blueprint. Journal of Service Research, 10(4), 318-334.

- Pinhanez, C. (2009). Services as customer-intensive systems. Design Issues, 25(2), 3-13.

- Ramaswamy, R. (1996). Design and management of service processes. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Ramírez, R. (1999). Value co-production: Intellectual origins and implications for practice and research. Strategic Management Journal, 20(1), 49-65.

- Ravasi, D., & Rindova, V. (2008). Symbolic value creation. In D. Barry & H. Hansen (Eds.), Handbook of new approaches to organization (pp. 270-284). London: Sage Publications.

- Reckwitz, A. (2002). Towards a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 243-263.

- Rittel, H., & Webber, M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155-169.

- Sangiorgi, D., & Clark, B. (2004, July 28). Towards a participatory design approach to service design. Paper presented at the 8th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, Toronto, Canada.

- Sangiorgi, D. (2009, April). Building up a framework for Service Design research. Paper presented at the 8th European Academy of Design Conference, Aberdeen, Scotland.

- Schatzki, T. R. (2001). Introduction: Practice theory. In T. R. Schatzki, K. K. Cetina, & E. von Savigny (Eds.), The practice turn in contemporary theory (pp. 10-23). London: Routledge.

- Schön, D. (1987). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

- Scheuing, E., & Johnson, E. (1989). A proposed model for new service development. Journal of Services Marketing, 3(2), 25-34.

- Shostack, G. L. (1982). How to design a service. European Journal of Marketing, 16(1), 49-63.

- Shostack, G. L. (1984). Designing services that deliver. Harvard Business Review, 62(1), 133-139.

- Simon, H. A. (1969). The sciences of the artificial (1st ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Simon, H. A. (1988). The sciences of the artificial (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Solomon, M. R., Surprenant, C., Czepiel, J. A., & Gutman, E. G. (1985). A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: The service encounter. Journal of Marketing, 49(1), 99-111.

- Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, “translations” and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907-39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387-420.

- Stigliani, I., & Fayard, A. L. (2010). Designing new customer experiences: A study of socio-material practices in service design [Discussion paper]. London: Imperial College Business School.

- Stuart, F. I., & Tax, S. (2004). Toward an integrative approach to designing service experiences: Lessons learned from the theatre. Journal of Operations Management, 22(6), 609-627.

- Tax, S., & Stuart, I. (1997). Designing and implementing new services: The challenges of integrating service systems. Journal of Retailing, 73(1), 105-134.

- Tonkinwise, C. (2003, April). Interminable design: Techne and time in the design of sustainable service systems. Paper presented at the 5th European Academy of Design, Barcelona, Spain.

- Ulrich, K., & Eppinger. S. (1995). Product design and development. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004a). Evolving to a new dominant logic in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1-17.

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004b). The four service marketing myths: Remnants of a goods-based manufacturing model. Journal of Service Research, 6(4), 324-335.

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2008a). Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 1-10.

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2008b). Why “service”? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 25-38.

- Verganti. R. (2009). Design-driven innovation. Changing the rules of competition by radically innovating what things mean. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

- Voss, C., & Zomerdijk, L. (2007). Innovation in experiential services – An empirical view. In Great Britain Dept. of Trade and Industry. (Ed.), Innovation in services (pp. 97-134). London: Dept. of Trade and Industry.

- Wheelwright, S., & Clark, K. (1992). Revolutionizing product development: Quantum leaps in speed, efficiency, and quality. New York: Free Press.

- Winograd, T., & Flores, F. (1986). Understanding computers and cognition: A new foundation for design. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Womack, J. P., Jones, D. T., & Roos, D. (1990). The machine that changed the world. New York: Rawson Associates.

- Zairi, M., & Sinclair, D. (1995). Business process re-engineering and process management: A survey of current practice and future trends in integrated management. Business Process Management Journal, 1(1), 8-29.

- Zeithaml, V., & Bitner, M. J. (2003). Services marketing: Integrating customer focus across the firm (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Zeithaml, V. A., Parasuraman, A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). Problems and strategies in services marketing. Journal of Marketing, 49(2), 33-46.

- Zomerdijk, L., & Voss, C. (2010). Service design for experience-centric services. Journal of Service Research, 13(1), 67-82.