Designing Service Evidence for Positive Relational Messages

Kathy Pui Ying Lo

Loughborough University, Loughborough, United Kingdom

This article discusses relational messages in the design of service evidence based on insight gained from empirical research. Photo elicitation and in-depth interviews were the key research methods used in understanding hotel guest experiences for design opportunities. The findings reveal that customers take service evidence and physical cues in the servicescapes to interpret both intended and unintended relational messages that communicate the service providers' perceptions about customers. Customers notice service evidence and judge whether service providers: (1) Care about their customers; (2) Consider customers as important; and (3) Trust customers. Their interpretations of relational messages influence their emotions and service experiences. In addition to face-to-face service encounters with staff, customers' interactions with service evidence are also important in shaping service experiences. Here, a framework is proposed to offer design strategies that convey positive relational messages in service evidence in terms of care, importance, and trust. This framework highlights three design strategies and three specific design emphases. The discussion draws on concepts and techniques including tangibility of service, customization, and empathic design. Examples are given to demonstrate the contexts in which the strategies can be applied, including retail, banking, transport, and hospitality. Key design questions and challenges for each strategy are also discussed.

Keywords – Service Design, Relational Message, Service Evidence, Experience Design, Visual Communication, Photo Elicitation.

Relevance to Design Practice – This article contributes the concept of relational messages in design to explain customers' interpretations of service evidence from a communication perspective. It also offers design strategies for designing service evidence that conveys positive relational messages which will lead to improvements in customer experience, service quality, and brand image.

Citation: Lo, K. P. Y. (2011). Designing service evidence for positive relational messages. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 5-13.

Received October 26, 2010; Accepted April 30, 2011; Published August 15, 2011.

Copyright: © 2011 Lo. Copyright for this article is retained by the author, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

Corresponding Author: K.P.Y.Lo@lboro.ac.uk

Dr. Kathy Pui Ying Lo is a lecturer in visual communication at School of the Arts in Loughborough University, U.K. She holds a PhD in Design and an MA in Design with distinction received from School of Design in The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. She is an internationally published design scholar and educator. Her research interests include experience design, design for emotions, service design, and visual communication. Her current research and publications focus on relational messages in design. She is also interested in qualitative exploration of people's experiences that aims at optimizing user experiences of design. Dr. Lo has a cross-disciplinary professional background in design and communication. She has worked across the industries of digital graphic design, mass media, public relations and research.

Introduction

In the most basic sense, service consists of the people, the processes, and the physical evidence of the experience (Titz, 2001). Service encounters include both tangible and intangible attributes. Designed objects in the service environment are sometimes referred to as “service evidence” because they are physical proof of service that has taken place. They are important components of the servicescapes and undoubtedly a critical part of service design. According to Mager, “Service design addresses the functionality and form of services from the perspective of clients. It aims to ensure that service interfaces are useful, usable, and desirable from the client's point of view and effective, efficient, and distinctive from the supplier's point of view” (Mager, 2007, p.355). Service evidence can be seen as the functional form that acts as the interface between service provider and consumers.

The importance of service evidence is further supported by the fact that the well-established SERVQUAL model and measurement tool of service quality devised by Parasuraman, Zeithaml and Berry (1988) included service tangibles as one of the five dimensions for measuring service performance (Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1994; Oliver, 1996). Other dimensions are reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy. In the widely used technique of blueprinting for service design (Shostack, 1982, 1984, 1987, 1992; Bitner, Ostrom, & Morgan, 2007), service evidence is the tangible manifestation of service that appears above the “line of visibility” in a service blueprint. The physical complexity of service evidence and servicescapes varies in different types of service. As shown in the typology of servicescapes (Bitner, 1992), they are designed to be more elaborate for interpersonal service (such as restaurants, hotels, hospitals) when compared to self-service (such as kiosks and automatic teller machines).

Berry and Bendapudi (2003) used the term “evidence management” to emphasize the importance of offering appropriate tangible cues in servicescapes because customers look for evidence of desirable service qualities by processing what they can see and understand. In the words of Berry and Bendapudi, the key to effective evidence management is to “clearly identify a simple, consistent message, and then manage the evidence – the buildings, the approach to care, even the shoelaces – to support that message, day in and day out” (Berry & Bendapudi, 2003, p.106). The scholarly works mentioned above demonstrate the important role of service evidence in service experiences. As such, it is worthwhile to devote research effort to study how service evidence influences customers' perceptions of service experiences.

Very often, concepts and methods of service design focus on the functions, the interactions and the emotions in customers' experiences with service evidence and servicescapes. This article proposes an alternative perspective to use to understand service evidence as a form of relational communication which influences customers' emotions and perceptions of service experiences. The proposition is based on findings of empirical research on hotel stay experiences. The following sections will elaborate on the research objectives, methods, critical findings regarding relational messages in service design, and useful strategies for designing service evidence that communicates positive relational messages.

Research Objectives and Methods

Situated in the cross-disciplinary context of service design, experience design, and hospitality, this qualitative design research aimed at studying hotel stay experiences and hotel guests' emotions for insights on design opportunities that will enhance hotel stays. The specific primary objectives were: (1) to understand emotions and meanings associated with hotel stay experiences; (2) to contribute conceptual understandings that illuminate the interconnections between design and customer emotions; and (3) to suggest design opportunities that will improve hotel stay experiences. Female business travelers were chosen as the research targets because they are a rapidly growing but under-studied traveler segment (World Tourism Organization, 2006). This research consisted of two concurrent studies. One of the studies used photo elicitation as the key data collection method, while the other used in-depth interview.

Photo Elicitation

Photo elicitation originates from visual research in anthropology (Collier & Collier, 1986). It is a research technique that combines the use of photographs with interview for data collection (Harper, 2002). Rose, a visual researcher, has a concise description of this technique: “Photo elicitation uses photos to encourage interview talk that would not be possible without the photos, and the photos and the talk are then interpreted by the researcher” (Rose, 2007, p.239). This method's key strength is the integration of visual and verbal data. It is particularly strong in three aspects: capturing contextual information, reviving memory, and facilitating reflection (Rose, 2007). Therefore, photo elicitation is an appropriate method for research on people's experiences.

With criterion sampling (Miles & Huberman, 1994), Hong Kong-based female business travelers who had upcoming trips were recruited as research participants in the photo elicitation study. Twenty-seven of them completed the research study. They took photos during hotel stays to show things, places, and events in hotels that evoked their emotions. After research participants returned from business trips, the author collected the photos and followed up by discussing the photos with research participants in individual discussions. Visual data about the triggers of emotions as well as verbal data regarding interpretation of emotions during hotel stays were collected. The photo elicitation study collected a total of 375 emotion-relevant photos covering hotel stay experiences in 45 hotels, 26 destinations, and 12 countries. Follow-up discussions with the 27 research participants yielded a total of 1022 minutes and eight seconds of audio recordings which were transcribed into 451 pages of single-spaced text for data analysis.

In-depth Interview

This research also included a separate study that employed in-depth interview as the key data collection method to understand hotel stay experiences. As a primary form of inquiry, in-depth interview (also known as “depth interview”) is the use of open, direct, verbal questions to elicit narratives and comments (Miller & Crabtree, 1999). The method is especially useful when participants cannot be observed directly (Sommer & Sommer, 2002; Creswell, 2003). The interview format also makes it possible for the informants to take a perspective on the past or discuss the future (Holloway, 1997). In the in-depth interview study, 32 Hong Kong-based female business travelers were interviewed in a one-to-one, semi-structured format. Discussions in the interviews focused on three aspects regarding hotel stays for business trips: pleasant experiences, unpleasant experiences, and anticipated experiences. The interview study generated a total of 1000 minutes and 16 seconds of audio recordings which were transcribed into 370 pages of single-spaced text for systematic coding.

The combination of photo elicitation and in-depth interviews not only yielded robust data, but also enabled understanding of guest experiences and emotions from both “micro” and “macro” perspectives. This was achievable because field-based data on specific cases of guest emotions were obtained through photo elicitation, while broader views about hotel stays based on research participants' past experiences and expectations were solicited through in-depth interviews.

Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed with multiple approaches for design-relevant insights, including enumerative analysis, thematic analysis, coding, and memoing. Data analysis for the photo elicitation study was underpinned by the appraisal theory in psychology. The core argument of appraisal theory is that an emotion involves an evaluation process (appraisal) that assesses the benefit or harm of a stimulus or situation (Lazarus, 1991; Smith & Lazarus, 1993; Roseman & Smith, 2001). A stimulus or event that matches or fulfills the person's concern(s) is appraised as beneficial and leads to pleasant emotion(s). Conversely, a stimulus or event that mismatches or contradicts one's concern(s) is appraised as harmful and results in unpleasant emotion(s). Appraisal theory is chosen as the foundation for the data analysis because it breaks down a case of emotion clearly into trigger, cognitive evaluation and emotional response. An analytical template based on appraisal theory was developed to facilitate data analysis in the author's research (Lo, 2007). Measures to reduce researcher's bias were taken, such as by asking additional coders to code part of the data, peer debriefing, and maintaining the transparency of procedures.

The comprehensive findings of the research include types of hotel-evoked emotions, their triggers, female business travelers' major concerns regarding hotel stays, design suggestions for improving hotel stays, optimal hotel stay scenarios, a conceptual model of emotional design for hotels, and the original concept of relational messages in design. This article concentrates on discussing relational messages in design with specific focus on implications for service design. Insights resulted from the empirical research are also presented as a framework of design strategies to inform service design.

Relational Messages in Service Evidence

According to communication theorists, all communication includes content message (what is actually said about a topic) and relational message (the sender's perception about the receiver) (Trenholm & Jensen, 2008). As people communicate, they are interpreting the factual meaning of the message as well as the relational meaning. The findings of the present research presented in this article hint that designed features in servicescapes also embody these two facets. This is because service consumers not only pay attention to objects and environments per se but also take them as cues to interpret the service provider's perception about customers. In the context of hotel stays, interpretation of relational messages embodied in hotel features plays a role in evoking hotel guests' emotions and changing the impressions of service experiences.

Design researchers who study design as communication process pointed out that users' actual interpretation of designed artifacts may or may not correspond with designers' intended meanings (Crilly et al., 2008a, 2008b). An understanding of how customers interpret relational messages in service features and how those interpretations influence their perceptions and emotions will be beneficial for designing service features that contribute to pleasant service experiences.

In hotel stay experiences, relational messages being interpreted from hotel features mainly focus on three aspects: care, importance and trust. Emotions often result when hotel guests interpret service evidence and hotel servicescapes to judge whether hotels:

- Care about their customers;

- Consider customers as important;

- Trust customers.

Care

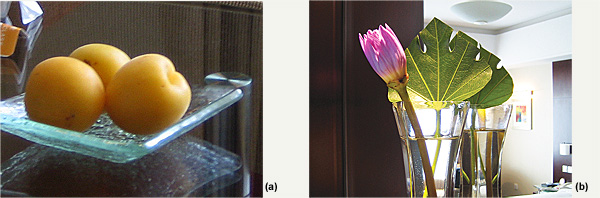

Well-considered, small details evoke pleasant emotions by conveying the relational message of care. Those tangible details are signs that the service provider has devoted extra effort to take better care of customers. In the cases of hotels, female business travelers interpret the level of care expressed by hotels from service evidence that shows anticipation of needs, high quality, flexibility to accommodate different needs, and communication of goodwill. Research participants pointed out that well-prepared small details represent sincerity in serving guests which reflects the hotel's good service spirit. For example, welcome fruit, an electric kettle and fresh flowers in hotel rooms are service evidence that often evoked delight as they show the hotel's thoughtfulness (See examples in Figure 1). A research participant remarked, “They make me think the hotel cares to go that little extra mile to make my hotel stay more comfortable.”

Figure 1. Details that convey care: (a) Welcome fruit and (b) Fresh flowers.

The quality of facilities and amenities in hotels can be interpreted as indicators of whether the hotel cares about the guests' comfort and wellbeing. For example, a research participant reported that she was touched because the hotel where she was staying showed thoughtfulness by providing high-quality slippers. She remarked:

The quality of those slippers was so good that I didn't have the usual negative thought when I stayed at other hotels, like: ‘Hey, what do I expect? It's just a hotel, not my home!' Those nice slippers were something that helped me adapt to the new environment easily. And this shows the hotel has considered whether the guests feel comfortable.

In another example, a research participant was delighted to find a little hat-shaped souvenir with a “Sleep well and pleasant dreams” message when she returned to the hotel room at night (See Figure 2). She said:

I felt the hotel's care and thoughtfulness... These gifts might be already charged in my room rate but still the hotel could have skipped them. Now they went the extra mile and it was really sweet and heart-warming for a hotel to wish the guests good night. I could feel a sense of human touch beyond mere housekeeping. The hotel is very considerate.

Figure 2. Souvenir with “sleep well” message.

As to hotel features that deliver negative relational messages regarding care, the most common examples were inadequate hotel features, such as the lack of electricity sockets, fixed showerheads, and an uncomfortable bed. One hotel guest was disappointed by the poorly maintained hotel bed, she made this remark about the hotel and its staff: “They don't care about their guests. They don't care if I can have a good night's sleep.”

Another common negative example is the two-in-one shampoo-conditioner, or the even worse three-in-one shower-gel-shampoo-conditioner. They are often interpreted as the hotel being uncaring or mean. One angry participant remarked that:

I hate three-in-ones. They are usually low-quality stuff that makes my skin too dry. If the hotel is considerate, they should offer at least three separate bottles of cleansing products: shower gel, shampoo, and conditioner. Not three-in-ones.

The abovementioned examples demonstrate hotel guests' interpretation of care and thoughtfulness (or the lack thereof) conveyed by hotels through service evidence. The interpretations influence their perception of hotels' service quality and their hotel stay emotions.

Importance

Customers pay attention to the servicescape to judge the importance of a certain type of customer to a company, and whether the company has shown consideration for that particular type of customer. For example, a research participant noticed an accessory container on the bedside shelf and interpreted it as the hotel's consideration for women travelers. She said, “This is definitely good for women, which is really a nice touch. You know, like rings, earrings, and stuff. You can put them somewhere and not lose them… Just like they were thinking about women.” Also, according to female business travelers, the content of toiletries is a good indicator to judge whether the particular hotel considers female guests as important. Some examples of toiletry items that indicate the importance of female guests include hand cream, cotton pads, head bands, and stockings. One female guest remarked, “Very often, you find shoe-polish and razors in hotels but never an extra pair of stockings. So I was really pleased to see the hand cream and stockings. I think this hotel takes female guests seriously.” These examples demonstrate how hotel features can convey the relational message of importance to the target customers.

A negative example in this regard is the use of “Mr.” as salutation for all written communication regardless of the gender of the guests in some hotels. Some research participants mentioned that greeting messages or welcome screens of TVs in hotel rooms sometimes addressed them as “Mr.” This minor error was interpreted as the hotels being male-oriented, not paying attention to female guests or individual differences. It was also seen as an indicator of the hotel's half-hearted effort to customize hotel messages.

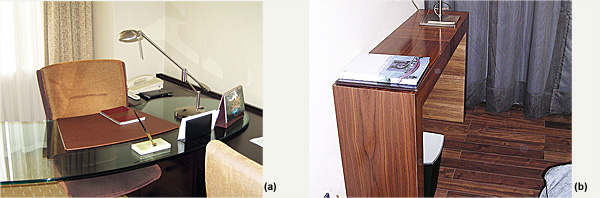

The set-up of the desk in the guestroom is a detail that is often interpreted by hotel guests to judge whether business travelers are important to a particular hotel. For example, Figure 3a is a photo taken by a research participant to show a practically designed desk she was pleased about. The desk area had adequate lighting, large desktop space, comfortable chair with adjustable height, easy connection to the Internet, and a handy telephone. Some research participants were pleasantly surprised to find extra details that facilitated work, such as a wide range of stationery, document trays, and desktop calendar. Those features indicate business guests' status as valued customers. As a contrasting example, the research participant who took the photo in Figure 3b said, “The desk is narrow like a bench. There's no chair and no Internet connection. When I saw this, my first thought was: This hotel is definitely not for business travelers.” The badly designed “desk” implies the hotel does not regard business travelers as important and delivers negative relational message to this traveler segment. Similarly, a research participant was angry to find three floors of shops for branded goods but only a small business center in a corner with no staff inside. To her, that meant the hotel does not regard business travelers as important.

Figure 3. Set-up of the desk for business travelers: (a) Good example and (b) Bad example.

Trust

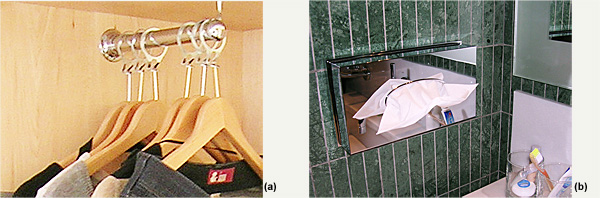

Subtle messages of distrust can be interpreted through details in the servicescape. Deprived functions and unnatural interactions with service evidence often trigger this type of interpretation. For example, a research participant talked about disappointment caused by “fake” hangers in a hotel room's closet (See Figure 4a). She complained:

They're not real hangers, because they're attached to the railing. So if you want to take out a hanger and then hang it on a chair or hang it on a door, you can't, because there's no hook… That's kind of a fake hanger. It shows that they think I'm going to steal the hangers. So it makes me feel not trusted.

Her unpleasant emotion actually stemmed from being assumed to be a thief when she interpreted the meaning behind the hangers' deprived function. Other similar examples that deliver subtle messages of distrust include a fixed tissue box in the bathroom (See Figure 4b) and a remote control attached to the TV set by plastic or metal string. Some research participants mentioned that no refill of consumable amenities (such as toiletries and tissue) also shows the hotel's distrust. One of them said, “That makes me wonder if they think I'm gonna steal the extra.”

Figure 4. Examples of distrust: (a) “Fake” hangers and (b) Fixed tissue box.

Regarding positive examples of cues in the servicescape that show the relational message of trust, one research participant was happy to find an umbrella placed conveniently in the hotel room for her to use on rainy days (See Figure 5). She shared:

It's often a nuisance when you suddenly need an umbrella but forgot to pack one. So it's really nice of the hotel to let guests borrow umbrellas for free. Like they are not suspecting we will steal them. The umbrella buys goodwill.

Another hotel guest was pleasantly surprised to find a desktop computer in the guestroom for her convenient use. She was impressed because more than offering just an Internet connection for hotel guests who bring along their own notebook computers, the hotel was generous and trusting enough to provide such an important and costly facility as desktop personal computer in the room for the convenience of the guests.

Figure 5. An umbrella was readily available in the room.

Implications for Design

The servicescape is the tangible manifestation of a company's service spirit. Some seemingly mundane details may trigger interpretation of messages, evoke customers' emotions, and make the service experience different. There is a relational dimension when customers perceive service evidence and servicescapes. They interpret physical evidence of service and tangible elements in the surroundings as cues to judge the relational messages delivered by service providers. Those interpretations evoke customers' emotions by influencing their perceptions of the service experiences, including service quality and brand image. The concept of relational messages in the design of service evidence explained in this article offers an alternative perspective to understand customers' service experience from a communication point of view. Its major implication is that to improve customers' service experiences, more effort should be devoted to find design opportunities that will improve details to convey the appropriate relational messages of care, importance and trust. Relevant design strategies are suggested and elaborated on in the next section.

Strategies to Design for

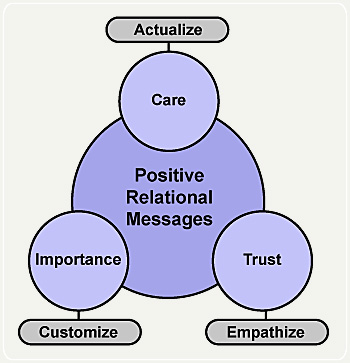

Positive Relational Messages

Based on insights gained from the empirical research, a framework is proposed to explain design for positive relational messages in service evidence (See Figure 6). This framework highlights three design strategies and three specific design emphases that will be useful for designing service evidence that conveys positive relational messages of care, importance, and trust. The design strategies are of value because they are applicable not only to the hotel industry but also to other types of service, as demonstrated by the examples below. Application of these strategies will lead to potential improvements in customer experience, service quality, and brand image. For purpose of clarity, the framework is presented visually as a concise diagram alongside detailed discussion. The following paragraphs elaborate on details of the framework, including the design strategies, practical examples, key questions for design, and challenges.

Figure 6. Framework of design strategies for positive relational messages in service evidence.

(Original work by Kathy P. Y. Lo)

Care: Actualize the Service Spirit in the Details

Design Strategy

The first design strategy is to convey care by actualizing the company's service spirit in the details of service evidence. Most service providers claim that they care about customers, and care is often high on the list of core brand values. The word “care” also appears frequently in advertisements and marketing materials to the degree of becoming a cliché. However, “care” is an abstract, intangible quality that is not obvious to customers. As Levitt contended, “Sellers of services face special problems in making customers aware of the benefits they are receiving” (Levitt, 1981, p.94). Also, it takes more than lip service to truly communicate care to customers; therefore, it is necessary to design service evidence that makes the concept of care tangible. These tangible cues communicate the relational message of care and make the service experience more pleasant. By paying close attention to the servicescape and by understanding customers' concerns, designers can discover opportunities to design details in tangible cues that communicate care.

Examples

For example, a furniture retail brand shows care in optimizing customer experience by providing measuring tapes, notepaper, and pencils in retail outlets free-of-charge. These practical tools allow customers (or would-be customers) to note the furniture's exact size measurements and price information easily before they make purchase decisions. These small details in the servicescape show the shop's careful anticipation of customers' needs and the effort in catering to those needs. Another example is the physical evidence left in hotel rooms to represent extra care in housekeeping service, such as the paper strap with the word “sterilized” placed on the toilet seat cover. It is a tangible cue to tell hotel guests that the staff has devoted effort in taking care of the room's cleanliness. Care is also effectively expressed in the evidence of evening turndown service - the bed cover is turned back and the lights are dimmed for relaxation. Also, bathrobes are prepared for use, and evening snacks are offered for enjoyment. These are tangible evidence that shows good hospitality.

Key Question

When using this design strategy, the key question that keeps the design focus clear is: What intangible aspects of the service can be translated into tangible evidence to show care to the customers?

Challenges

Selection of appropriate details for design is the challenge of this design strategy, especially for mature service categories. When competitors offer similar quality of service, it becomes critical to look for design opportunities and excel at the level of details. As customers' expectations are ever increasing and the level of service quality can only go up, actualizing caring service spirit through details becomes increasingly competitive. Another challenge is to balance actualization of service with environmental concerns. As it is unethical and uneconomical to produce excessive service tangibles, choice of materials and procedures for reuse and recycling become important considerations in the design of service evidence.

Importance: Customize for Needs and Preferences

Design Strategy

In order to design effectively for communicating the relational message of importance, the service providers or designers must be very clear about who their target customers are. They must have a thorough understanding of the target customers' needs and preferences so that appropriate service evidence and servicescapes can be customized accordingly. Designing to convey the relational message of importance requires in-depth understanding of the target customers' needs and preferences as well as technical knowledge to enable customization of service features.

Examples

One example is a bank's dedicated counter for elderly customers aged 60 or above. It is customized to provide bank statements and communication materials in large prints, simplified signature procedure, and seats in the queue-up area. These features especially designed for the elderly deliver a positive relational message to elderly customers as they are tangible cues that show the bank considers the elderly as important customers. Another example is the positive relational message expressed through customized hotel features that suit the preferences of individual repeat customers. Increasingly, hotels make effective use of customer databases to save information on individual guest's preferences of in-room settings and food choices. It is often a pleasant experience for a repeat guest to find hotel room features customized to her favorites in her next stay, such as the right choice of newspapers, welcome fruit, and type of pillows. In addition to a high level of thoughtfulness, these customized features also indicate the importance of repeat guests as valued customers.

Key Question

When designing for the relational message of importance, the key question to ask is: Which service features can be customized according to the needs and preferences of the target customers to show the importance of these customers?

Challenges

The main challenge of applying this design strategy is in overcoming technical difficulties, as customization usually involves careful design and co-ordination of interfaces for customization, backstage staff procedures, inventories of products, and the use of databases for recording and retrieving information on customers' preferences. Technical expertise and iterative testing are indispensable to ensure smooth implementation of customizable features.

Trust: Empathize for Optimal Interactions

Design Strategy

Trust is the subtlest among the three core relational messages discussed here; therefore, it is the most difficult one to state a design strategy for. Instead of deliberately designing service evidence to communicate trust, the focus of design effort should be on optimizing customers' interactions with service features to avoid communicating distrust. To achieve this, service providers and designers should develop empathy for customers by immersing themselves in the customer experience. This necessary step helps them consider the service experience from the customers' perspective, and identify awkward interactions with service features that may communicate negative relational messages. According to McDonagh (2008), the essence of empathic design approaches is to ensure that design outcomes are appropriate, relevant and more balanced in both functional and supra-functional aspects by using research methods that expand the “empathic horizon” of designers. “Empathic horizon” refers to “the ability of the designer to empathize, and to some degree understand the experiences of others in further removed context” (McDonagh, 2008, p. 103). The insights resulting from empathic design approaches will help optimize service features and avoid communicating unintended negative relational messages to customers.

Examples

Consider the examples of “fake” hangers and no refilling of consumable amenities in hotel rooms which were mentioned earlier in this article as delivering a negative relational message of distrust. Using a mystery shopper would enable the service designer to quickly identify these problematic features and correct them to avoid communicating an unintentional message of distrust to hotel guests. Another example concerns train service and involves service procedures. In some countries, it is still common to employ staff to check tickets on trains. This procedure communicates an unintended relational message of distrust to passengers. It also makes passengers' in-train experience less pleasant as they are interrupted for ticket checks. It is a rather undesirable service touchpoint which is especially obvious when it happens in a train service that has computerized most service components, such as ticket sales, seat reservation, and platform entrance. This example actually points out a problem rather than provides an answer. Those train companies should design service features that solve this problem.

Key Question

The key question for this design strategy is: How to optimize customers' interactions with servicescapes by empathizing with customers to avoid communicating messages of distrust?

Challenges

The prerequisite for this design strategy is open-mindedness of the design and management team to adopt empathic research and design methods. The next challenge is to find the appropriate research and design methods that will generate relevant insights for the particular service. The journal paper by Saco and Goncalves (2008) offers a concise list of service design tools. The book on experience design for healthcare written by Bate and Robert (2007) also provides useful overviews of experiential research and design methods which can be applied to service design in general. Resources published by practitioners such as the method cards by IDEO (2003), experience design cards by Shedroff (2009), and the article on experience prototyping by Buchenau and Fulton Suri (2000) are some practical references.

Conclusion

This article contributed an alternative perspective for understanding service design by discussing the concept of relational messages in the design of service evidence and servicescapes. As discussed in the article, service evidence is taken by customers as cues to interpret the service provider's perception about customers. Designed features in the servicescape embody a relational dimension as they reflect whether service providers care about their customers, whether customers are considered as important, and the degree of trust towards customers. Hence, design is not only experienced functionally, aesthetically, and symbolically, but also interpreted relationally. This article provided real examples of customers' nuanced interpretations of relational messages in the hotel context.

Another main contribution of this article is a framework of design strategies for communicating positive relational messages in service evidence. The framework succinctly articulates design strategies in terms of care, importance, and trust. The design strategies are applicable to a wide spectrum of service industries, as demonstrated by examples in the discussion. The framework also offers key design questions and challenges to guide the application of the suggested strategies.

The discussions in this article can serve as the starting point for further research effort in exploring the concept of relational messages in service design as well as in other contexts. There is potential in extending the concept of relational messages in design and applying the related design strategies to types of service with less elaborate servicescapes and interpersonal interactions, such as product-service systems, self-service systems and remote service. Also, more research on the concept of relational messages and related design strategies in other design contexts may yield interesting insights that illuminate the role design plays in mediating human connections.

Acknowledgments

The empirical research was conducted at School of Design, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. The author would like to express heartfelt gratitude to Professor Lorraine Justice for her advice and support. Also, special thanks to Professor John Heskett, Professor Deana McDonagh, Professor Judith Gregory, Professor Pieter Desmet and Professor Kaye Chon for their valuable advice. The author would also like to thank Miss Dona Loo, Miss Carol Wong, Miss Becky Fung, Miss Ellie Chiu, and Miss Florence Leung for their help. This research would not be possible without the help from the wonderful research participants: A sincere “thank you” to all of them.

References

- Bate, P., & Robert, G. (2007). Bringing user experience to healthcare improvement: The concepts, methods and practices of experience-based design. Oxford: Radcliffe.

- Berry, L. L., & Bendapudi, N. (2003). Clueing in customers. Harvard Review of Business, 81(2), 100-106.

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57-71.

- Bitner, M. J., Ostrom, A. L., & Morgan, F. N. (2007). Service blueprinting: A practical tool for service innovation (Working paper). Tempe, AZ: Center for Services Leadership, Arizona State University.

- Buchenau, M., & Fulton Suri, J. (2000). Experience prototyping. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Designing Interactive Systems (pp. 424-433). New York: ACM Press. Retrieved June 20, 2007, from http://www.viktoria.se/fal/kurser/winograd-2004/p424-buchenau.pdf

- Collier, J., & Collier, M. (1986). Visual anthropology: Photography as a research method. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

- Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Crilly, N., Good, D., Matravers, D., & Clarkson, P. J. (2008a). Design as communication: Exploring the validity and utility of relating intention to interpretation. Design Studies, 29(5), 425-457.

- Crilly, N., Maier, A., & Clarkson, P. J. (2008b). Representing artefacts as media: Modelling the relationship between designer intent and consumer experience. International Journal of Design, 2(3), 15-27.

- Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17(1), 13-26.

- Holloway, I. (1997). Basic concepts for qualitative research. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

- IDEO. (2003). IDEO method cards. Palo Alto, CA: IDEO.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Levitt, T. (1981). Marketing intangible products and product intangibles. Harvard Business Review, 59(3), 94-102.

- Lo, K. P. Y. (2007). Emotional design for hotel stay experiences: Research on guest emotions and design opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2nd IASDR Conference on Design Research: Emerging Trends in Design Research [CD-ROM]. Hong Kong: The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

- Mager, B. (2007). Service design. In M. Erlhoff & T. Marshalle (Eds.), Design dictionary: Perspectives on design terminology (pp. 354-357). Basel: Birkhäuser.

- McDonagh, D. (2008). Do it until it hurts! Empathic design research. Design Principles and Practices: An International Journal, 2(3), 103-109.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Miller, W. L., & Crabtree, B. F. (1999). Depth interviewing. In B. F. Crabtree & W. L. Miller (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (pp. 89-107). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Oliver, R. L. (1996). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. London: McGraw-Hill.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V., & Berry, L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12-40.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V., & Berry, L. (1994). Reassessment of expectations as a comparison standard in measuring service quality: Implications for further research. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 111-124.

- Rose, G. (2007). Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Roseman, I. J., & Smith, G. A. (2001). Appraisal theory: Assumptions, varieties, controversies. In K. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal processes in emotion (pp. 3-19). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Saco, R. M., & Goncalves, A. P. (2008). Service design: An appraisal. Design Management Review, 19(1), 10-19.

- Shedroff, N. (2009). Experience design cards 1. Indianapolis, IN: New Riders.

- Shostack, G. L. (1982). How to design a service. European Journal of Marketing, 16(1), 49-63.

- Shostack, G. L. (1984). Designing services that deliver. Harvard Business Review, 62(1), 133-139.

- Shostack, G. L. (1987). Services positioning through structural change. Journal of Marketing, 51(1), 34-43.

- Shostack, G. L. (1992). Understanding services through blueprinting. Advances in Services Marketing and Management, 1(1), 75-90.

- Smith, C. A., & Lazarus, R. S. (1993). Appraisal components, core relational themes and the emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 7(3/4), 233-269.

- Sommer, R., & Sommer, B. (2002). A practical guide to behavioral research: Tools and techniques. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Titz, K. (2001). The impact of people, process, and physical evidence on tourism, hospitality, and leisure service quality. In J. Kandampully, C. Mok, & B. Sparks (Eds.), Service quality management in hospitality, tourism, and leisure (pp. 67-83). New York: Haworth Hospitality Press.

- Trenholm, S., & Jensen, A. (2008). Interpersonal communication. New York: Oxford University Press.

- World Tourism Organization. (2006). Mega-trends of tourism in Asia-Pacific: June 2006. Madrid, Spain: World Tourism Organization.