Political and Cultural Representation in Malaysian Websites

Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia

Acknowledging cultural differences in the development of visual interface design is an important factor in many multicultural settings. This research investigates the cultural and ethnic mix of Malaysia by taking an official government website as a case study. In Malaysia, Malays, Chinese and Indians live in a pluralistic society but are treated by the government as separate communities. Each ethnic group has been able to retain its cultural identity through maintaining and being allowed to maintain their individual languages, religion and traditions. Malaysia’s brand of multiculturalism endeavours to consider diversity as a positive resource, with government policy promoting tolerance between the major ethnic groups to maintain a harmonious and unified society. Vision 2020 has been initiated by the Malay Government to fulfill this goal of promoting intercultural understanding within Malaysia’s multi-ethnic society. This research investigates effective strategies for the development of a truly representative visual interface design within a multicultural context in the spirit of Vision 2020. This project adopts Power Distance (PD) from Hoftstede’s model of cultural analysis, and Aaron Marcus’s approach to multi-dimensional web-interface analysis to identify current representations of multicultural Malaysia. “Cultural Markers” and case study analysis are used to investigate cultural inclusion and to accommodate a more accurate expression of revised government policy.

Keywords – Cultural Representation, National and Global Cultures, Web-interface Analysis, Cultural Markers.

Relevance to Design Practice – Given the applied nature of their training, most interface designers would have no formal concept of cultural representation. This paper, through the use of mood boards, cultural markers and site analysis provides both tools and insight into cultural representation.

Citation: Tong. M. C., & Robertson, K. (2008). Political and cultural representation in Malaysian websites. International Journal of Design, 2(2), 67-79.

Received March 3, 2008; Accepted July 31, 2008; Published August 31, 2008

Copyright: © 2008 Tong and Robertson. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

*Corresponding Author:tongadrian@hotmail.com

Introduction

Contemporary Malaysia is a multicultural country with three main ethnic groups, each with their own language and religious practices. According to Wan (1983), “Malaysia is unique in its population distribution, where the number of indigenous Malays almost equals that of the immigrant Chinese and Indians put together” (p. 59). The government is concerned with the distribution of resources and opportunities for these groups within the nation. Malays, Chinese and Indians are treated pluralistically by the government, and each ethnic group has been able to retain its cultural identity through the maintenance of individual languages, religions and traditions. Though the maintenance of identity sounds idealistic, this national endeavour has been carried out at quite a social price in that despite considerable economic growth in recent decades, social and economic policy has largely focused on the Malay fraction. Considerable and disproportionate resources have been directed towards Malays with the intent of raising their social, economic and educational profile in the hope of repairing the social inequalities which triggered social tension, most notably in the anti-Chinese race riots in 1969.

Malaysia has embarked on nearly four decades of highly successful development that has led the country and its population out of the third world. Malaysia now finds itself a player in the globalized world economy where national issues are giving way to international priorities. Globalization tends to take ethnic difference for granted and pushes those national tensions into the past when the focus was different. The Malaysian Government has been cautious in setting a near-future goal for multicultural integration, but it would be reasonable to expect that today we should be able to detect a gradual move towards those new aspirations.

Recent Malaysian prime ministers have been heralding a more idealistic future of greater equality promoting intercultural understanding within Malaysia’s multi-ethnic society. As set forth in a series of government announcements in ‘Bangsa Malaysia’ (‘Malaysian Nation’), ‘Smart Partnership’ (Mahathir, 1991) and ‘One System for Malaysia’ (Badawi, 2004), the revised vision of the government is to focus on a multicultural society and equality between the different ethnic groups. These goals have been most recently articulated in a proclamation called Vision 2020, where Malaysia is described attaining a new national identity that is different from the pluralist society of the colonial period (Mahathir, 1991), to be ultimately realized by the year 2020. However, the issue of national integration in a multicultural society has never been well resolved in Malaysia. This idea needs to be considered in relation to the population of Malaysia, the structure of the society, and the distinctive characteristics of its ethnic composition and stated government policy.

This paper looks for evidence of these policy changes through reading the design and visual evidence provided by contemporary Malaysian websites. A contradiction to be explored is the current situation where Malaysian commercial websites have already made the changes that acknowledge ethnic equality, while the Malay Government remains the only force retarding ethnic inclusion while speaking in an almost exclusively Malay voice. Most of the government websites continue to privilege Malay users through language and cultural elements.

This paper uses Semiotic Structural Analysis to seek out and map the ‘Cultural Markers’ of language/typography, layout, colour, pattern and image in order to discover the code and structure of the existing Malaysian websites. This analysis was inspired by Hoftstede’s (1980) landmark cultural research in which Power Distance (PD) emerged as a powerful force in Malaysian culture; and Aaron Marcus’s (2002) approach to multidimensional web-interface analysis. A case study analysis of the Malaysian Library is also conducted in order to demonstrate ethnically inclusive visual interface design.

Reading the Cultural Setting through Web Design

The exponential expansion of the World Wide Web is one of the greatest developments in communication over the last decade. The internet is fast becoming the major source of information and a popular source for business information and commercial access, while providing a new platform for social networking that appears to be connecting to a passionate social need, as seen through sites such as Facebook. The representation of life on the internet has become a public and private imperative for people across the globe. This has been the case for both developed and developing nations and has certainly altered the context of cultural and multicultural representation, which provides a challenge for those that seek to control perceptions of policy, organizations and identities. Representation of these things has become a concern for government, business and individuals. Robbins and Stylianou (2002) state:

Developing an effective multinational Internet presence requires designing web sites that operate in a diverse multicultural environment. Globally accessible websites likewise have the potential to inform, and include, various nations around the world in a large scale information sharing in order to reduce any exclusion effects. (p.205)

This research project is concerned with the issue of social and cultural integration and the human computer interface, where culture includes not only ethnicity but also customary behaviors, values and communicative styles. The influence of cultural representation on the web user is a complicated variable, because it is difficult to establish which aspects of culture influence user behavior and to what extent cultural background influences understanding. The multicultural interface is about making websites an effective form of communication, in terms of recognition of cultural differences and sharing comprehensible communications.

Malaysian government official websites currently emphasize a Malay monoculture in a way that significantly ignores multicultural users’ cognitive elements that assist in comprehension as they respond to the graphic and textual content. These websites illustrate dominant Malay identity in images, logo and language. In addition, although Bahasa Malay is the official language of the major population group, other languages such as Mandarin and Hindi are barely, if ever, used in the official government websites. This contrasts some commercial websites which target specific cultural groups though the use of their languages. At the same time, an argument can be made that English should be used on websites across all cultural groups because it is commonly understood by all cultures in Malaysia and is not as tied to any specific ethnicity. English is also the language of globalization.

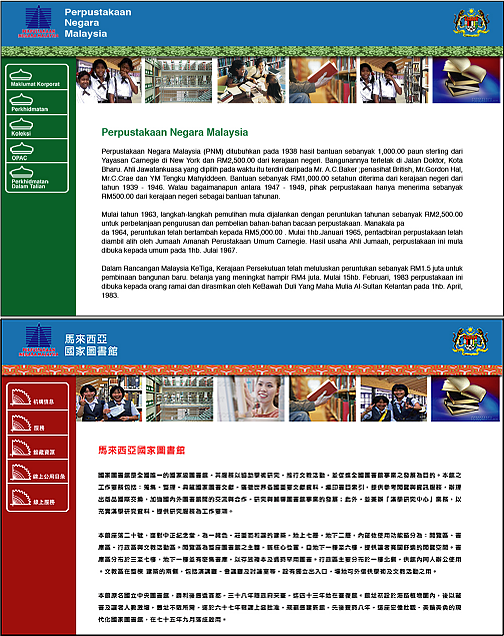

Typical characteristics of Malaysian Government sites can be found at The National Library of Malaysia website (www.pnm.my). Dominant, due to its size, colour and centrality, is the large image of the library building – a unique structure based on the tengkolok, a Malay chief’s folded cloth and ceremonial hat – itself a symbol of Malay culture and power. Tengkoloks typically have a strong woven ikat pattern which here determines the dominant colour of the building and is repeated in the coloured band that runs across the top of the webpage. The default language of the site is Bahasa (with English as a second option) and official government logos dominate the pages. A typical Malaysian commercial site, Celcom (www.celcom,com.my), by contrast uses only English, displays a racially neutral blue sky, and generally employs a group of models of mixed race and gender in a spacious, neutral, generally centered, modern layout. Images in commercial websites are usually of mixed ethnic groups, therefore relationship oriented and multicultural.

Most of the official Malaysian government websites are designed exclusively to privilege the Malay group, but it is not often realized or acknowledged that the websites are culturally unappealing and inaccessible for other national cultural groups, such as the Chinese and Indians. Web users from different cultural backgrounds may conclude that their culture has been disregarded and they will have difficulty identifying with the virtual world of government websites. The identity of Malay and Chinese cultures will be visualized and represented within the web interfaces during this research process. This cultural complexity should be reflected in web design. Thus, Luna , Peracchio, and Juan (2002) stated:

… the cultural schemas we develop are a result of adaptation to the environment we live in and the way we have been taught to see things in our culture. As such, web users from different countries tend to prefer different web site characteristics depending on their distinct needs in terms of navigation, security, product information, customer service, shopping tools, and other features. (pp. 391-410).

This argument reflects an international, as opposed to intra-national, approach concerning the use of appropriate cultural strategies for e-marketplaces. In contrast, this research is more concerned with multicultural communication on the interface, reflecting the current theoretical research in the field of human computer interface. Hence, the key issue is to more fully understand the representation of multicultural values within the human–computer interface and how to facilitate this.

The importance of visual symbolism for Malaysia’s ethnic groups must be considered when assessing the effectiveness of the Malaysian government official websites as a medium of multicultural communication and more inclusive government rhetoric. An effective interface design will incorporate at least key elements of these to attract recognition. This research focuses on visual forms of communication based on cultural traditions to which people are accustomed. As culture is understood as the learned behaviour of a group, these behaviours affect social and communication practices. Cultural rules may change across different cultural groups making cultural understanding difficult to map, but website interface design must attempt to reflect these complexities in a multicultural context.

Cultural Markers: The Major Signifiers in Visual Interface Design

This exploratory design research uses visual content analysis and a case study to explore data patterns analyzed and collected via the Cultural Markers Method (CMM) and identified using Mood Boards of diverse cultural aspects. It is hoped that as a result of this study, future designers or researchers may be able to better determine and understand the appropriate cultural visual elements that belong to a category of the web interface. The Cultural Markers explored in this study were Language, Colour, Pattern and Image. By mapping these four attributes, we should better demonstrate the characteristics of particular web interface design with the appropriate patterns of cultural and social interface that will demonstrate the intended cultural message of current Malaysian interface design, and how new government social policy might be expressed in the future.

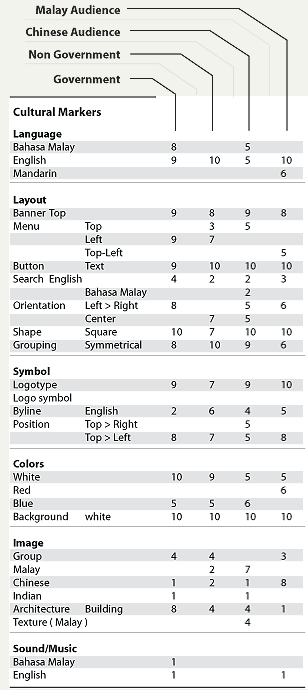

The Visualization of Culture: Mood Boards

In order that cultures might be represented visually it is first necessary to compile a visual repertoire of signs that might be relevant to particular cultures. In this case, we chose to collect cultural images that were produced across the breadth of a culture and might also reflect those attributes we were seeking to cover (for the same inclusive reasons) in the Cultural Markers Method (see next section) which are language/typography, layout, symbol, colour, image and sound. In this research a collection of Malay and Chinese images only attempted representing the major two ethnicities in the Malaysian context. Indian and possibly East Malaysian ethnic groups would also deserve representation in a more truly national analysis.

Being practicing and researching designers, we chose mood boards to be the format and organizational structure for these collected images. We chose to develop highly gridded mood boards because that ‘order’ provided the opportunity to more fully compare and identify the particular aspects of culture in each cultural grouping. Mood Boards have traditionally been presented in a more impressionistic, ‘un-gridded’, collaged composition, but since we had to survey a wide range of cultural elements such as architecture, handicrafts, textiles and design elements of type, image, colour, patterns, signs and symbols, we felt a more structured presentation allowed for easy comparison between cultures (Garner & McDonagh-Philp, 2001).

Mood Boards include everything related to cultural visual representations. Mood Boards are commonly used in the design and advertising industries as a systematic way of presenting visual components and elements from particular design perspectives. Person (2003) states, “Mood boards are a collection of visual images gathered together to represent an emotional response to a design brief” (p. 2). This process has been widely used in advertising design to explore images that describe a given theme. In this research, the Mood Boards process started with collecting and ordering relevant social and cultural signs and symbols useful in the construction of particular cultural representations. Using this method, designers can identify dynamic visual cues that represent particular sets of cultural elements. For instance, Malay patterns consistently appeared in the Mood Boards through applied Islamic geometrical shapes. Red could be characterized as a Chinese preference due to its culturally positive attributes to wealth, prosperity and well being.

The Visualization of Culture: The Cultural Markers Method (CMM) of Analysing Web Interface Characteristics

In order to use the CMM, a detailed structural analysis was made of 40 Malaysian websites that were divided equally into four categories: Government, Non-government, Malay and Chinese. (The complete list of researched sites is given in the Appendix along with their respective URL’s. A better understanding of the CMM analysis can be attained through visiting them). CMM is undertaken to perform an interface analysis of a number of government and non-government websites designed for Malay and Chinese users, taking ten examples for each category. Different cultures will typically use particular, ideal expressive characteristics. The interface of a website can serve as a model for identifying and separating websites that are recognizable and acceptable to a multicultural society. In this method, some of the visual characteristics and navigation features should be identified to establish how they relate to the entire interface of a website in a particular cultural group. To this end, CMM will be able to demonstrate the presence or absence of certain visual characteristics, and identify the characteristics of the most culturally appropriate and recognized symbols. The elements of analysis for CMM will include a search for the following six characteristics related to a website: Language, Layout, Symbol, Color, Image and Sound/Music. These elements are important to the cultural web interface. Research studies by Galdo (1996); Fernandes (1994); and Russo and Boor (1993) conclude that while designing a website, it is essential to consider such cultural factors as icons, symbols, colour and language.

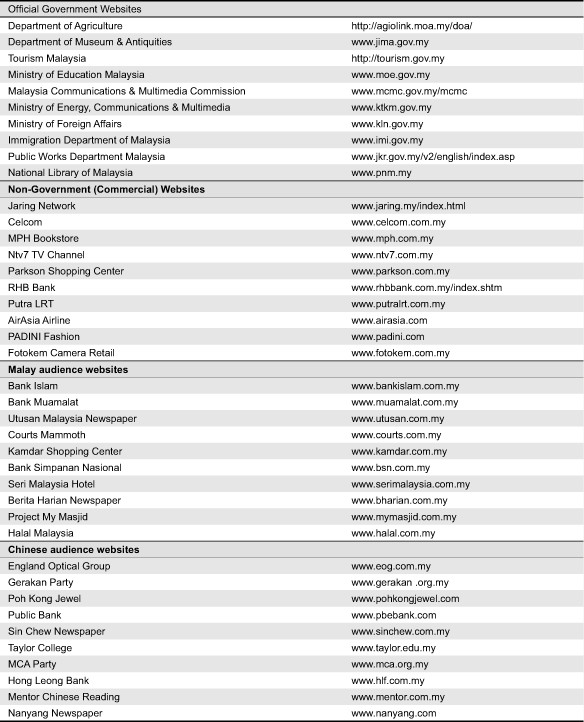

Table 1. Statistical summary of the outcomes of the Cultural Markers Method. A summary of all the websites (including their URLs) referenced for this table can be seen in the Appendix.

Each of these sites was analyzed through the types of signs they represented related to the aforementioned six characteristics. Language: indicates the speech used by a particular group of people including dialect, syntax, grammar and letterform. Layout: indicates the preferences (often a suppressed part of the cultural tradition) used in the order and organization of information and/or images. Symbol: in this case indicates the way the site and/or corporate identity is represented through logo, logotype and logo placement. Colour: refers to the colours of site backgrounds, typography and images. Image: is perhaps the most obvious cultural indicator as it may express identity through depiction of cultural form from the social realm or that of cultural production e.g. the arts, crafts or architecture. Sound / music: is rarely used in Malaysian sites but is of course culturally significant.

Figure 1. Malay (top) and (below) Chinese visual culture mood boards. These mood boards were created to indicate cultural markers in the Style Menu constructed to demonstrate cultural representation in Malaysian web sites.

Summary of the Analysis Outcomes of The Cultural Markers Method

Using content analysis of the listed web sites (see Appendix), the goal was to identify Cultural Markers in the web interface. Singh and Baack claim “content analyses are a reputable and a widely used tool for conducting objective, systematic, and quantitative analysis of communication content” (Berelson, 1952; Kassarjian, 1977). Cultural Markers (Badre, 2000) are adapted and modified to analyze examples of four different categories of websites, according to Language, Layout, Symbol, Colors, Image and Sound/Music. The Mood Boards will expose the patterns and variety of cultures in the interface design elements through comparison and contrast. Barber and Badre (1998) state, “Cultural Markers are interface design elements and features that are prevalent, and possibly preferred, within a particular cultural group” (p. 1). Such markers signify a cultural affiliation. A cultural marker, such as a national symbol, color, or spatial organization, for example, denotes a conventionalized use of the feature in the web site, not an anomalous feature that occurs infrequently.

These research findings show that the web interfaces are not a neutral form of cultural representation. A comparison of mean differences in each data category shows some differences exist between Government and Non-Government (Commercial) websites, for example English is the major language for the Commercial websites whereas for the Government websites, Bahasa Malay is the default language with English as the only second language option. Government and Malay audience websites prefer design with top-banners on the site. The majority of significant differences between the Government and the other three categories of websites in this analysis are differences largely concerning menu layout, pattern, images and language of the websites. The principal differences are elaborated below.

Language

The most distinctive cultural symbol is language. The CMM analysis of results showed that English is the most common language used in all websites, although Bahasa Malay is predominantly used in the official government websites. Mandarin is used for specific websites that target a Chinese audience in order to be more accessible for these users. In everyday usage, English seems to be the most commonly shared language of Malaysian society. English carries some baggage in Malaysia (as the language of the old colonial master) but the added bonus to its use is that it has become the first global language, and its inclusion increases the transparency and accessibility of Malaysian websites.

Layout

Cultural preferences can be clearly identified in the design of the layout; factors like the positioning of the banner and menu on the top of the page, the shape and language used on text buttons, geometrical shapes and the popularity of symmetrical design. Government websites tend to have a layout from left to right. In contrast, the Non-government (Commercial) website layout focuses on symmetrical/centralized design components. Yu and Roh (2002) suggested “Appropriate design layout provides web visitors with a contextual and structural model for understanding and accessing information” (p. 2).

Symbol

Symbols are important elements of cultural meaning. Cyr and Trevor-Smith state, “Symbols are ‘metaphors’ denoting actions of the user” (Barber & Badre 2001, p.6). The use of particular symbols is particularly relevant, for instance, when they clearly represent one ethnic group over another. The architectural design of the National Library of Malaysia depicting the shape of a

Malay Chief’s folded cloth hat (tengkolok), even at that

subliminal level is reinforcing the dominance of Malay culture over others in Malaysia. So symbols (if we are to see them as logos of corporate or personal identity) should not all be derived from only the dominant culture.

Colour

Barber and Badre (2001) list several colours and their connotations in various cultures. Red, for example, means happiness in China, but danger in the U.S. When colour is applied to interface design, it may have an impact on cultural recognition and user’s expectations and satisfaction. The most common colours used in the government websites used in this research seem to be white and blue, while Chinese audience websites favour red. Green symbolizes growth and peace in Malay culture. Morrison and Conway (2004) state, “The colour green is increasingly associated with the environment. It is also the colour of Islam, which means that it is not a good choice in countries dealing with conflicts over Islam”.

Image

Images tend to hold the clearest and most literal cultural information – information closest to everyday cultural experience. Government websites seem to use almost exclusively ethnic Malay imagery. The non-government (commercial) website uses more inclusive images, like the mixed race group of young women in the Malaysian Bank advertisement.

Sound/Music

Sound or music is not commonly used in Malaysian websites. None of the sites in this investigation included music. This CMM would enable designers to give hierarchy to the most important features or cultural interface for a particular set of multicultural users. The characteristics of websites have been identified and they serve as groundwork for establishing guidelines used in designing an interface for users from particular cultures within a multicultural society. For instance, the design of a particular characteristic of the website interface, like buttons, can signify or reflect a cultural interface for the website. However, the interface should display specific elements which give the website cultural recognition for users from individual cultures. Whether it represents or contains their ‘voice’ is often a matter of the details related to such characteristics.

Case Study: The National Library of Malaysia

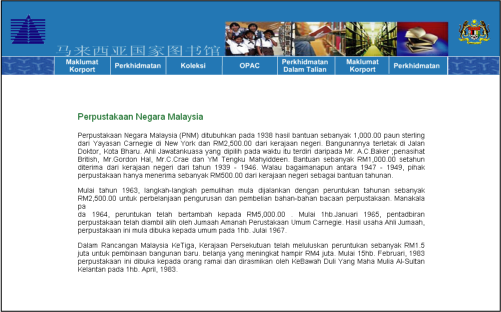

The best way to demonstrate the effectiveness of cultural representation is by ‘reading’ the signs of current websites. In this case we have chosen the Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia (National Library of Malaysia www.pnm.my) website as it is a flagship Malaysian government institution that represents the cultural life and focus of the country. If compared to the other key Malaysian Government websites, it carries very similar and uniform characteristics in terms of their representation, language options, use of signs and logos, hierarchical representation etc.

In order to critique the National Library of Malaysia site in a way compatible with the CMM analysis adopted above, we will order our case study under the same headings.

Language/Typography

Most important is that the Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia (National Library of Malaysia) [PNM] Website defaults to Malay text in its browser; the only alternative language option is to click English Version. There are no Chinese or Indian options. These priorities clearly privilege the Malay-speaking user. It should be noted that many headings (nearly all Government Departments) remain in the Malay language even when the English version is chosen. Once you move beyond the home page, it seems that the English option is much less consistent. On the PNM Website for example, when you select the English version:

- if you wish to read the Message from the Director General, Puan Siti Zakiah Aman, her message is only available in Malay.

- the continuously scrolling Latest News box is only in Malay.

- Under Training Programmes despite the English heading HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMMES 2008 all of the text is only available in Malay.

- All National Library of Malaysia Acts and Regulations and Annual Reports are in Malay only.

Layout

The most recent PNM Website uses a hybrid of menu buttons. The most typical Malaysian Government location for buttons is across the top frame of the page, and this site locates its Home, Language Version, About PNM, Site Map and FAQ buttons at this location. The more functional buttons (Collections, Services, E-Catalogues etc.) are located on the left. Layout is generally set over three or four columns and overall shows little design discipline in terms of its layout.

Symbol

The most striking aspect of the PNM’s identity on the home page is given by the dominant, centrally-placed building which houses the Malaysian National Library. As mentioned, it was designed to reflect the shape, colour and pattern of the traditional Malay chief’s headgear - the tengkolok - which is a symbol of pride and respect in Malaysian culture. The building itself is shaped like a giant tengkolok and covered in highly patterned blue tiles in the traditional songket design. A detail of the songket design is repeated as a pattern on the banner of the library across the top of the webpage. Aaron Markus describes such symbolic inclusion (or exclusion/omission) as metaphor for real core values of the site. In this case, the symbolism clearly references only Malay culture through Malay craft symbolism (referencing traditional Malay arts and crafts) and Malay power symbolism (referencing the chief as the pinnacle of Malay social power structure, but also referencing a sign of wisdom, masculinity and age).

Colour

The deep red border to the website is not typical of Malaysian culture, but it is not the typically brighter, warm red popular with the Chinese either.

Image/ Pattern

All images in the PNM website are Malay. Viewing the site, one could be forgiven for thinking that Malaysia was a Malay monoculture. The most dominant image (first mentioned above under Symbol) is of the unmistakably Malay tengkolok design of the library building. Exclusively Malay themes are also true of all images that include people. Malay dominance is especially evident on the Training programmes page where every member of the public depicted as well as training professionals are from the Malay ethnic group.

Sound Music

The PNM site provides no music. Gert Hofstede was given the opportunity to conduct his famous study into cross-cultural values when he was employed by IBM in the 1960’s and 70’s. IBM was then one of the largest global companies and Hofstede distributed multilingual questionaires to over 72 countries. This research was eventually presented and discussed in Hofstede’s (1980) Cultures Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations where he distils his research findings into four (and in later editions 5) internationally distributed sets of social values or dispositions; these being power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity and long-term/short-term orientation. Hofstede was able to measure the ratio of all of these polarities in every national culture. The attraction of his research for this study is that in one of the polarities Malaysia actually tops the national rankings – expressing power distance more strongly than any other culture in the international study. Power Distance implies that in institutions and organizations within Malaysia, people expect and accept that power is distributed unequally.

Asma and Pederson (2003, p.74) identified these hierarchical relationships through the use of names among the different cultures of Malaysia. In such High Power Distance cultures, people are sensitive to behavior that shows respect and obedience to senior authority figures. High Power Distance is exemplified in the PNM website by the dominance of the tengkolok – the inclusion of which is reinforced by layout, pattern and image. In the website, a corporate logo and an official seal of the country are clearly displayed on the top banner of the page; a sign that represents phenomena that tend to focus on centralized political power. All of these elements reinforce the concept of High Power Distance and signify Malay authority.

This cultural dimension also indicates the value of addressing the “behavioural” component of culture. It focuses on an individual’s relationship with society or other individuals. Lee and Green (1991) state, “Societal norms and societal pressure have been shown to have a significant impact on behavioural intention formation in collectivist societies” (p.300). Also, Han and Shavitt (1994) state, “Research on advertising in such countries shows advertising to be congruent to their cultural identity, with an emphasis on group-consensus appeals, family security, and family ties” (p.12). In collectivist societies, a stronger focus is on the group, and individuals are associated with societal chains. The group concept, focusing on group decision-making, takes precedence over the individual values.

Malaysia’s culture emphasizes the importance of relationships and group consciousness. According to Asma and Pedersen (2003):

Malaysians also think highly of those who are loyal, moderate in their way, disciplined and obedient ... Malaysia is a collectivist society of kita (we) in which people from birth onwards tend to identify themselves with a family, community or organization.

(pp. 66-68)

Referring to the PNM website, the website in fact expresses kami (meaning ‘We’ formally and representitive of an instiution) rather than kita, (which implies ‘We’ in the sense that an informal friendship group would use the word), thereby exclusively addressing only the Malay ethnic groups and ignoring a wider incorporation of other Malay ethnicities which would be described as kita. According to Singh and Pereira (2005), “...collectivist societies emphasize in-group obligations, interdependence, and preserving the welfare of others” (p. 77). The Malaysian government official websites are not yet emphasizing this theme, compared to the commercial sites. Advertising in commercial organizations is focusing on the appeal relating to interdependent relationships in the collectivist societies. For example, Tsuruoka (1993, pp. 24-25) points out the significance of a full-page advertisement by Bank Bumiputra, the state-owned Malay bank, last year that carried the headline “Bank Bumiputra Salutes the New Generation” and showed three young professional women, a Malay, a Chinese and an Indian all walking together on a city street.

Cultural Markers

Hofstede’s (1980) model and Marcus’s (2000) user-interface components address specific aspects of visible language related to culture in interface design. These combinations provide both visual syntax and semantic elements that are associated to cultural areas in relation to particulars of presentation. Cultural Markers serve a major role in cultural interface design, combining with the Hofstede and Marcus frameworks to more easily achieve cultural sensitivity for Malaysian society. Barber and Badre (1998) show that there are established interface design elements and features of a website among a given culture. Barber and Badre (1998) state, “Cultural Markers are interface design elements and features that are prevalent, and possibly preferred, within a particular cultural group. Such markers signify a cultural affiliation” (p. 1).

Sun (2001) states, “In multilingual websites, cultural markers work as a layer of context which conveys the contextual information to the international users and helps them establish their familiar cultural frames so that they can understand and navigate through the information product” (p. 100). In short, Hofstede’s cultural framework could become useful to interface design combined with other precise methodologies. Hofstede’s cultural dimension is still a major influence in the research fields, and it can be clearly identified that those cultural markers would be applicable to the scenario of Malaysia’s multilingual websites.

Sun’s research aims to seek social and cultural factors for designing usable web interfaces with exploration of Cultural Markers. He identifies some methods of defining criteria, searching effective strategies and evaluating current practices for cultural interface design, with a clear focusing on four major categories of cultural markers. They are visuals, colours, language and page layouts. The preliminary findings of Sun’s research are (2001, p. 99):

- Culture is an important design element in multilingual web page design. When users browse the web pages, they will sub-consciously apply their cultural preferences to evaluate the design of web pages.

- Cultural markers are noticeable in multilingual web design. When users browse web pages, they often use the clues of picture, icon, shape, color, texts and tone to judge whether the site targets them.

- Cultural markers can increase the usability of multilingual web pages. Cultural markers have great effects on users’ satisfaction with a specific multilingual web page and can ease users’ navigation.

- Users from different cultures prefer different modes of cultural markers.

- People from particular cultural backgrounds prefer particular cultural markers.

Sun’s research shows that websites use market specific Cultural Markers to include and get appropriate acceptance from its target audience. Sun (2001) states, “Cultural Markers can be regarded as one of the techniques for information visualization on the multilingual websites. They work as a layer of contexts and offer contextual clues for users to access information online” (p. 99). As Schriver (1997) suggests, “readers need to interact with multiple clues to arrive at an interpretation of a text” (p. 45). This concept is exactly the same applied to the online user. So, the Cultural Marker can be achieved through cultural sensitivity. It brings closer the interval between the users and organizations, as it is executing the method to design localized websites on the cultural level, peculiarly in multilingual websites.

There are a number of research studies that recognize the impact of culturally appropriate elements on interface design, besides the research that has been previously mentioned. Smith, Dunckley, French, Minoch, and Chang (2003) conducted research on the concept of cultural attractors to define the interface design elements of the website that reflect the signs and their meanings to match the expectations of the local culture. This research model is rather close to the scope of this research project that focuses on the major cultural elements: language, colours, symbols and patterns. The cultural attractors include: colours, colour combinations, banner adverts, trust signs, use of metaphor, language cues, navigation controls and similar visual elements that together create a ‘look and feel’ to match the cultural expectations of the users for a particular domain.

Developing Culturally Representative Style Menus

Mood Boards and CMM are the design processes which provide the visual references and the analysis for each Style Menu representing specific forms of cultural integration. There are many potential ways of representing cultural forms, but we developed a ‘form’ designers readily understand – the Style Menu. In this paper we present three different Style Menus: 1) Specific Cultural Representation, 2) Culturally Integrated Interface, and 3) Standardized Interface (Culturally Suppressed). The three Style Menus demonstrate how different web maps mirror actual cultural formations in relation to the elements of language, colour, pattern and image. They demonstrate what visual elements of a particular culture are associated with the different interface features used in our case study of the PNM’s website. In the creation of the Style Menu, thumbnails were sketched based on the mapping from the CMM analysis, documenting how the interface should be represented in the Style Menu. This permitted a close examination of examples, focusing on the content and composition of the presentation of the interface, which is easy for the designer to interact with.

Wroblewski (2002) states, “When creating Web sites, we rely on the site’s personality to provide emotional impact and a consistent point of view for our audience. The personality of your site provides the answers to the ‘who’ and ‘why’ questions of your audience in a clear descriptive voice” (p. 175). Appropriate visual interface elements not only create an impact on the audience, they also provide distinction and appeal to the overall visual interface of the website. The design objective of the Style Menus is to create meaningful and effective communication that give cultural recognition and meaningful experience to particular cultural audiences.

Graphical features on the web interface are increasingly important to support cultural identity in relation to an increasingly ‘cross-cultural’ globalised media, as well as recognition of the multicultural in countries such as Malaysia. In addition, most of the graphical features are likely to be more subconscious in that presentation is a subliminal preference, rather than a specifically identified cultural characteristic, such as language or clothing

The four attributes of color, pattern, language, and image respond to the emotional appeal of the visual interface for the user. These attributes provide a connection for exploration and interaction between the website and the user. This approach tends to maximize the multicultural concept, and it allows designers to focus their ability and knowledge on formalising cultural elements in the interface design through the proposed Style Menus.

Attribute: Colour

This research project aims to identify the symbolism of colour in particular cultures and ethnic groups, inquiring mainly about the uses of colour in decoration, clothing and family life, which can be seen in the different Mood Boards.

By recognising particular colours as Cultural Markers for each ethnic group, a website can be designed with an appropriate tone, using culturally specific colour schemes. A website can avoid using the favourite colour of each ethnic group (red and green in this case) as each colour means something specific and signifies a specific identity. So it is often better to seek a solution by using appropriate colours that are suitable for all groups, in order to establish general recognition of a website, such as the PNM.

In Style Menu-3, colour has been utilised by featuring nature and the environment as reflecting the characteristics of Malaysia. The colour of the natural environment shares a common useage amongst all Malaysians. Hutchings (2004) states, “Rice coloured yellow with turmeric or saffron is widely used in custom in India, Pakistan and Malaysia” (p. 61). Style Menu-3 also demonstrates the research of Wiegersma and Vander (1998) in that blue is the color chosen most often in their cross-cultural study, as well as being the corporate colour that identifies the PNM website. Caivano (1998) states:

… colors are used as signs, the functioning of color in the natural and cultural environment, the way organisms identify colors for survival and their importance to food gathering, the physiological and psychological effects of color and its contribution to man’s well-being, and the influence of color on behavior. (p. 394)

Galdo and Nielson (1996) established that colour and screen design principles have different psychological and social associations in a variety of cultures. Colour creates a different recognition and reaction in the different users. In Style Menu-1, Specific cultural representation is proposed using specific colours to represent the different target user groups. The prototype uses green to correspond with the Malays and red with the Chinese. It signifies a representation of the culture and acknowledges that we often remember something through a colour. These Style Menus demonstrate cultural recognition and emotional response from the users.

Figure 2. Style menu 1 –Specific cultural representation: Malaysian (top) and Chinese (bottom).

In Style menu 1 readers would elect to go to a particular ethnicity which would be fully represented in its own language, colour and symbols.

Colour can represent different meanings in different cultural groups, but it can also identify difference in similar forms of representation. For example, the Chinese give each other a red envelope (called Hongbao) during Lunar New Year. It is a symbol of celebration, good wishes and good fortune. The Malays hand out cash contained in green envelopes called Duit Raya during the Hari Raya Aidilfitri in Malaysia. Each group carries out similar cultural practices, but in different ways. As demonstrated, cultural representation is at the root of cultural differences. Colour is significant in this cultural context; designers must realise that signs do not strictly belong to one group or another, but can diverge according to the context. Referring to the above example, Green or Red might be a signal in one context, but a symbol in another form. In Style Menu-2 (Culturally Integrated Interface), avoidance of any symbolisation of cultural colour, in particular Red and Green, in this case is evident.

Figure 3. Style menu 2 – Culturally integrated interface.

In Style menu 2 colours and images representing particular ethnicities keep rotating so that no ethnicity dominates. Drop-down menus offer language choice and specific ethnic orientation.

Attribute: Pattern

Pattern is one of the cultural visual representations that provide a physical form of cultural knowledge. Pattern can be attached to anything that comes from a way of life or culturally specific knowledge. Most patterns are culture-specific. When analysing a website, special attention should be given to whether and how the pattern is understood in a particular culture. The importance of visual pattern for Malaysia’s ethnic groups must be considered when evaluating the effectiveness of the PNM website as a medium of multicultural communication and of more inclusive government rhetoric. An effective web design will incorporate at least key elements of these to attract recognition.

Patterns were designed to fade in and out around each of the different cultural elements in Style Menu-2. The animated pattern provides recognition of cultural elements for the user. Chao, Pocher, Xu, Zhou and Zhang (2002) state, “[…] Asian people are polychromic, that is, doing many things at once” (p. 189). The pattern plays a supportive role in the cultural representation of Style Menu-2 because of its rendered and animated forms of textures to enhance the cultural recognition. In contrast, Style Menu-1, designed for Specific Cultural Representation, demonstrates a pattern based on individual cultural representations. In this Style Menu, the differences of visual representations in Malay and Chinese groups have been taken into consideration, as shown in the mosque that symbolises Malay Islamic culture and the traditional fan that symbolises Chinese culture.

Attribute: Language

As seen on Style Menu-2, the Culturally Integrated Interface, the main heading and navigation text superimposes three languages in the one interface design, which can reflect the emotion and cultural recognition that allow users to more easily identify with the interface. Hence, the appearance of language formalises a semiotic of visual recognition. Style Menu-3, the Standardized Interface, demonstrates the use of one language (English) as a cross-cultural visual interface in the website. English is widely used in Malaysia. Although people have different local languages and cultures, the learning of English and its use is common in everyday life. Hence, the English language could be commonly used in Style Menu-3.

Figure 4. Style menu 3 – Standardized Interface (culturally suppressed).

In Style menu 3 colours and images are purposely kept culturally neutral. This is the style of globalization.

Attribute: Image

Malaysia is a country based on a collectivist oriented society. Most web interfaces tend to emphasize images of group and community including family or group-oriented themes. The images are consistent with collectivism as demonstrated in Style Menu-2. Amant (2005) states, “[…] cultural differences in visual expectations can affect entire sites that use a particular kind of visual” (p. 77).

Style Menu-3 shows a lesser level of Power Distance in terms of the layout design, particularly in the attributes of Images. The design of Style Menu-3 has been proposed to match Hofstede’s cultural dimension of Power Distance, with lower Power Distance involving more creative and flexible composition. Style Menu-3 is more deliberately designed in a way that is innovative, aesthetic and unrestricted, so that the visual interface of the website can fulfill the announcement of the Malaysian government on Vision 2020, in encouraging a multicultural society in the nation. Interestingly, this matches the style mostly used in Malaysian commercial sites, which unlike the government sites are intent on capturing the whole market as directly as possible. Moreover, Style Menu-3 provides uncomplicated and easy access to the website and creates an emotional response in users who have multilingual proficiency, have lived in more than one ethnic group, and have more multicultural knowledge than those who live in and belong to only one ethnic group.

In Style Menu-3, aspects are categorized relating to personal cultural knowledge as well as the knowledge of other cultures and multilingual language proficiencies. The users would have expectations of how they would like the visual interface to be. Hofstede (1997) asserts, “Individuals with more cultural knowledge are able to distance themselves from their own cultural assumptions and are aware of the limitations of their inherited cultural ‘software’” (p. 231). Therefore, Style Menu-3 is proposed as being designed for users with more cultural knowledge who have less cultural identification without the loss of effectiveness of cultural recognition.

The 2020 policy intends to bring the country into ‘national wealth’ and maintain a Collectivist society. The 2020 policy also implies a reduction of Power Distance in the society. Style

Menu-3 is suggesting the components of these issues and demonstrating an enhanced cross-cultural interface model that reflects positive development as a contribution to the nation. Style Menu-2 demonstrates a Collectivist dimension to the visual interface design. It shows cross-cultural images on the website, emphasising group harmony, trust and ‘we’ relationships.

Amant (2005) states “The cultural expectations of what features an item – or visual representations of an item – should possess, however, can affect the credibility and the acceptability of visual displays.” The visual attribute, including preferences of particular geometric shapes and presentation of images, plays a crucial role in visual recognition for different cultural groups. Visual representation assists the user to emotionally identify and enhance visual interface recognition. According to Amant, “the presence or absence of a single design feature can be enough to affect the credibility of an image or of an overall web site. Different cultures, for example, can associate different meanings with the same colour”. These associations could affect how individuals from different cultures perceive the meaning of a particular image.

Summary

Understanding cultural differences is an issue that has been of increasing concern in the design of web interfaces. Some of the literature demonstrates that human computer interaction and user interface design theories along with cultural studies can develop conceptual frameworks for analyzing the impact of cultural factors on the effectiveness of various user interface designs, especially in this time of globalization.

Most research studies do not discuss/demonstrate interface design for users from different cultures within the same country, as in the case of Malaysia’s multicultural society. A review of the literature reveals that culture undeniably has an impact on users’ response to interface design. However, most of the previous cross-cultural studies have focused on questionnaires about human computer interaction rather than behavioral data surveys. One exception is Evers and Day’s research on the comparison of culturally stimulated design preferences. Evers (1997, p.261) argues that three issues need to be considered:

- There are few publicly available studies that investigate the effects of localized and non-localized interfaces on users’ perception and understanding.

- Little empirical work has been done investigating the differences in cross-cultural perception and understanding of interface design and

- Not many studies use methods such as observation or case studies to investigate cross-cultural aspects of interface design.

In this study we have sought to fill those gaps and provide a template for future development more readily accessible to designers and other non-social scientists.

It is not easy for designers to develop a sophisticated understanding of culturally sensitive visual interface design. Although there are a number of examples of existing research on cultural frameworks and theories, it is difficult for designers to identify the appropriate model for a particular multicultural society. Given this lack of supporting guidelines that can make possible the practical development process, this research project focuses on developing a set of broad multicultural guidelines, which combines the theoretical model of cross-cultural design and practical development through the Style menus.

Clearly there is a difference in the representation of multi-cultural and mono-cultural societies but the question that must always be asked and answered through the web design is “Who is the target audience?” This is why Malaysia makes such an interesting case study. Malaysian government sites have presented themselves as if they were representing a Malay monoculture. One can understand the historical origins of this position but in the light of recent prime-ministerial announcements one would also expect to see a change of direction - something like those offered in the Style Menus. In the Malaysian context, the multi-cultural model is already demonstrated and practiced in most Malaysian commercial websites. Here the motive appears to be different; to capture as much interest across the society without causing exclusion or ethnic preference while still appealing to the idea of national unity, a sense of community, and collaboration. There may be a lag between political rhetoric and action, but the age of globalization can be tough on the narrow and insular nationalistic vision and much more encouraging of wider inclusion without having to lead to the worst scenario of all – that of the non-culture, which carries the identity of nobody at all.

References

- Amant, K. S. (2005). A prototype theory approach to international web site analysis and design. Technical Communications Quarterly, 14(1), 73-91.

- Asma, A., & Pedersen, P. B. (2003). Understanding multicultural Malaysia: Delights, puzzles & irritations. New York: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Badawi, A. A. (2004, January 31). One system for Malaysia. New Straits Times, 1.

- Badre, A. N. (2000). The effects of cross cultural interface design orientation on world wide web user performance (Tech. Report: GIT-GVU-01-03). Atlanta, GA: Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved March 23, 2005, from http://www.cc.gatech.edu.au/gvu/reports/2001/abstracts/01-03.html

- Barber, W., & Badre, A. (1998). Culturability: The merging of culture and usability. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Human Factors and the Web. Retrieved December 10, 2007, from http://zing.ncsl.nist.gov/hfweb/att4/proceedings/barber/

- Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research. New York: Free Press.

- Chao, C., Pocher, T., Xu, Y., Zhou, R., & Zhang, K. (2002). Understanding the polychronicity of Chinese. In D. Guozhong (Ed.), Proceedings of the 5th Asian-Pacific Computer-Human Interface Conference (Vol. 1, pp. 189-196). Beijing, China.

- Cyr, D., & Trevor-Smith, H. (2004). Localization of Web design: An empirical comparison of German, Japanese, and U.S. website characteristics. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 55(13), 1-10.

- Evers, V. (1997). Cross-cultural understanding of metaphors in interface design. In C. Ess & F. Sudweeks (Eds.), Proceedings of the Conference on Cultural Attitudes towards Technology and Communication. Retrieved January 10, 2008, from http://staff.science.uva.nl/~evers/pubs/catac98.pdf

- Fernandes, T. (1994). Global interface design. London: Academic Press.

- Galdo, D., & Nielson, J. (1996). International user interfaces. New York: John Willey and Sons.

- Garner, S., & McDonagh-Philp, D. (2001). Problem interpretation and resolution via visual stimuli: The use of ‘mood boards’ in design education. The Journal of Art and Design Education, 20(1), 57-64.

- Giacchino-Baker, R. (2000). New perspectives on diversity: Multicultural metaphors for Malaysia. Multicultural Perspectives, 2(1), 20-22.

- Han, S. P., & Shavitt, S. (1994). Persuasion and culture: Advertising appeals in individualistic and collectivistic societies. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 30(4), 8-18.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Hofstede, G. (1997). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. London, McGraw Hill,

- Kassarjian, H. H. (1997). Content analysis in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 4(1), 8-18.

- Kottak, C. P., & Kozaitis, K. A. (2003). On being different: Diversity and multiculturalism in the North American mainstream. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Lee, C., & Green, R. T. (1991). Cross-cultural examination of the Fishbein behavioral intentions model. Journal of International Business Studies, 22(2), 289-305.

- Luna, D., Peracchio, L. A., & Juan, M. D. (2002). Cross-cultural and cognitive aspects of web site navigation, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(4), 397-410.

- Mahathir, M. (1991). Malaysia: The way forward – Vision 2020. Paper presented at the Inaugural Conference Meeting of the Malaysian Business Council. Retrieved January 20, 2004, from http://smpke.jpm.my1025/vision.html

- Marcus, A. (2000). Cultural dimensions and global web user-interface design: What? So What? Now What? Retrieved April 15, 2007, from http://www.amanda.com/resources/hfweb2000/AMA_CultDim.pdf

- Morrison, T.& Conway, W.A. (2004) The colour of money: Getting through customs. Retrieved May 26, 2006, http://www.getcustoms.com/2004GTC/Articles/iw0298.html

- Russo, P., & Boor, S. (1993). How fluent is your interface? Designing for international users. In Proceedings of the INTERACT ‘93 and CHI ‘93 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 342-347). New York: ACM.

- Schriver, K. A. (1997). Dynamics in document design. New York: John Wiley.

- Singh, N., & Pereira, A. (2005). The culturally customized web site: Customizing web sites for the global marketplace. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Smith, A., Dunckley, L., French, T., Minoch, S., & Chang, Y. (2003). A process model for developing usable cross-cultural websites. Interacting with Computers, 16(1), 63-91.

- Sun, H. (2001). Building a culturally competent corporate web site: An exploratory study of cultural markers in multilingual web design. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference on Computer Documentation (pp. 95-102). New York: ACM.

- Tsuruoka, D. (1993). Malaysia: Prop for pluralism. Far Eastern Economic Review, 156(6), 24-25.

- Yu, B., & Roh, S. (2002). The effects of menu design on information-seeking performance and user’s attitude on the web. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(11), 923-933.

- Wan, H. (1983). Race relations in Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Heinemann Educational Books (Asia).

Appendix

The following four groupings of websites were analyzed for this study: