Towards Female Preferences in Design – A Pilot Study

Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore, Singapore

The aim of this paper is to investigate gender perception as it relates to product language, identity, and preferences. Responses were gathered through a mixed methodology of descriptive and qualitative study, using data from semi-structured interviews with 72 participants, of which 38 were male and 34 were female. Three types of consumer products were selected as the design stimuli, combined with a selection of product properties having aesthetic, functional and social associations. In the interviews, initial responses from the respondents were mixed and associated with reservations about the choices available. Their immediate choices of models revolved mostly around expected ranges, reflected especially so in the choices of fragrance bottle designs. More in-depth interpretive and qualitative evaluation of the choices was conducted by suggesting schemes, references and associated expressions for analyzing keywords. References for directing gender-oriented design are proposed as a supplement to future design procedures. The study concludes by demonstrating how these schemes and references could help designers, for example by enhancing future designs of healthcare devices for women, with particular attention to creating a new culture of self-awareness and well-being.

Keywords - Design Attributes, Design Research, Gender Analysis, Product Perception.

Relevance to Design Practice - A range of consumer products were used as design instruments, combined with knowledge related to aesthetic, functional, and social associations to investigate issues related to product language, identity, and gender tastes and preferences. Recommendations are made for designing products that are more profoundly dedicated to the needs and preferences of the genders.

Citation: Xue, L., & Yen, C. C. (2007). Towards female preferences in design – A pilot study. International Journal of Design, 1(3), 11-27.

Received February 11, 2007; Accepted October 14, 2007; Published December 1, 2007

Copyright: © 2007 Xue and Yen. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

*Corresponding Author: akiyc@nus.edu.sg

Introduction

For the past fifty years, the idea of successful marketing has involved an effort to see products from the customer’s or user’s point of view. One possible route into the mind of the customer/user, often recommended in the literature, is the study of market segmentation variables (McKenna, 1988; Dexter, 2002). This approach provides a method of identifying subgroups of consumers who are likely to respond in a relatively homogeneous way to products or brands (Brennan, 1995; Schiffman & Kanuk, 1994), and many products are thoroughly researched from functional and marketing points of view with the idea of such subgroups in mind. However, although the issue of "gender" is almost invariably cited as one of the important segmentation variables (Popcorn & Marigold, 2000), little design research had been undertaken until recently to establish whether or how men’s and women’s responses to consumer products and brands differ, and whether there should be any systematic approaches for designers to identify their specific and respective preferences.

Recently, product design has given more consideration to the influences of affective issues of users (Desmet, 2002). It has emerged that emotional factors play a crucial role in the user-product relationship and not only with regard to physical functionality (McDonagh, Bruseberg, & Haslam, 2002; Desmet & Hekkert, 2002). These emotional factors are referred to as supra-functional needs, and include the emotional, inspirational, social and cultural needs of the user (McDonagh et al., 2002; McDonagh-Philip & Lebbon, 2000). The challenge of design today is therefore beginning to move beyond the stage of functionality and usability of consumer products toward a more fully pleasure-based approach in design. While designers are now drawing distinct differences related to gender needs, desires and preferences, there is at the same time an increasing trend to create and adopt non-gendered designs (Carlton, 1997), with the tactful aim of not "discriminating" and of displaying an acceptance of alternative lifestyles in today’s society. However, recognizing that there will always be differences in gender preferences and needs, especially when it comes to certain personal products such as cosmetics, non-gendered designs are not always applicable in all situations (Basow, 1992; Moss, 1999; Popcorn & Marigold, 2000). Currently, the exploration into genuine product character for the purposes of design investigation may be limited, but such exploration is beginning to establish its foothold in the design arena. Therefore, this study attempts to investigate language, identity, and gender tastes and preferences as they relate to consumer products, with the aim of creating principles that will be applicable to designing products that are more profoundly dedicated to gender needs and preferences.

Research Design and Procedure

Identification of Product Properties

Studies (Forty, 1986; Crozier, 1994; Baxter, 1995; Bürdek, 1996; Alreck, 1999; De Angeli, Lynch, & Johnson, 2002; Gotzsch, 2003) show that consumers are increasingly aware of product differentiation in terms of form and design, as well as of their status as users. Marketers, likewise, can testify that consumer product choices are based on more clearly defined properties (Morello, 1995; Janlert & Stolterman, 1997; Jordon, 1998; Crossley, 2003; Cho & Lee, 2005). Models have been developed to explain how products elicit emotions, and tools such as the "Product Emotion Measurement Instrument" (PrEmo) and the "Product and Emotion Navigator" (Desmet, 2002) have been developed to support design professionals in evaluating the emotional responses of consumers toward existing and new designs. In this respect, three common types of product properties or dimensions that relate to consumer buying behavior—namely, aesthetic, functional and social properties (Crozier, 1994; Jordon, 1998; De Angeli et al., 2002)—were selected for use in this study. Using these three product properties as references, a questionnaire was designed for interviewees to rank three different groups of common daily consumer products currently available in the market (mobile phones, mp3 players, and fragrance bottles). Definitions and applications of the three product properties—aesthetic, functional, and social—are discussed in the following sections.

Aesthetic

Aesthetics, as defined in the context of product design, refers to the comparative study of sensory values experienced in relation to products. These values can be in relation to overall product appearance or to some particular product detail or design feature. As human perception is dominated by vision, product style is usually an abbreviation for visual style, thus making aesthetic considerations a basic foundation for beginning the exploration undertaken in this study.

Functional

The functional perception of a product involves an instrumental description of the procedures used to operate it and its overall degree of effectiveness, efficiency or efficacy. A deeper understanding of a product’s operative abilities may be related to issues of problem-solving or reasoning, or to interaction and communication of information. Hence, in determining whether products are functional or not, they can be viewed with respect to the presumed effectiveness they have (based on a visual evaluation of the product interface design) or may have for their users or for society in general (based on past user experiences and reviews).

Social

Although products are not uniforms or badges that, when worn or carried, divide users into categories, they do carry with them subtle concepts that relate to an understanding of social norms. In this sense, products can be seen as influencing social identities or social affiliations. This influence can be seen as two-fold (Ortony, Clore, & Collins, 1988; Desmet, 2002):

- It can relate to the inclination of people to anticipate future use or possession of a product that they see: When people see a car with the Ferrari symbol on it, for example, they may think immediately of the prestigious status that they would gain by owning and driving such an expensive car. This evokes a kind of reaction that involves a yearning to be socially affiliated with the product, and a desire to select the product because of its social status rather than its form or function. They are somehow convinced that using or owning this product would result in a social life or a social status that seems desirable.

- It can relate to the ability of products to symbolize past events. For example, seeing a mobile phone (handcellphone.com, n.d.) might remind some people of a toy they once cherished in their childhood days. In this case, the product symbolizes a meaningful personal event that is not something held in common with others. In this case, their selection of the product may be based on subjective, intrinsic reasons, rather than the product’s form or function.

The relative weight of each property will vary according to the task to be executed with the product, the context of interaction with the product and the nature or personality of the user. It is assumed, further, that a number of mutual influences affect the aesthetic, functional and social properties of any particular object. For this reason, user satisfaction, taste, and preference are determined by the convergence of the perceived quality of each property. This convergence can be determined and evaluated through a process of stimulus selection.

Stimulus Selection

The researcher A. Forty (1986) provides several examples from the period 1895 to 1980 comparing designs of everyday items for men and women such as watches, hair brushes, pocket knives and razors. The appearances of these objects reflect stereotypical ideas of men as plain, strong, and assertive, and of women as "decorative," weak, delicate, and sensitive (Forty, 1986). However, as an understanding of aesthetic and social properties gradually gained greater importance in product design during the course of the 20th century, it is now evident that such designs as described by Forty may not reflect different tastes and preferences of the genders as such, but that these differences might, rather, have been exaggerated in the past as a way to advocate standards of good design and good taste, and to establish the existence of design "classics" (Baxter, 1995).

With this in mind, it was decided that three types of products would be selected for this study out of a range of common consumer products that both genders would have a chance to deal with in their daily activities (i.e., activities revolving around work, sports, home, travel, hobbies, personal care, etc.) Eventually, two types of consumer electronic products related to communication and entertainment (mobile phones and mp3 players) and one type of personal lifestyle product (bottled fragrances) were selected as test objects for the purpose of conducting a gender-related preference analysis aimed at defining the characteristics best-suited for different gender-oriented product schemes. Ten variations of each product type were finally selected as stimuli for the respondents, who were asked to rank them from most well-liked model to least well-liked model (see Figures 1 to 3).

The ten variations of each product type were chosen by means of a selection study that was conducted by asking 30 respondents to suggest different models of the three types of products. They were instructed that the selected models should cover diversity (in terms of design) of the available product variations on the market at the time. More specifically, in order to provide better coherence among the variations selected, the respondents were also instructed to apply two criteria in making their selections: (1) the selections should be on the market within the same time frame, so that when the participants saw the choices, they would be less affected by differences related to market time factors, and (2) the selections should show discernable differences in designs when grouped together, so that there would be enough variety to allow for the participants to indicate clear choices.

The final stimuli selections were then reviewed and re-confirmed by a panel consisting of three professional designers, from the National University of Singapore’s Department of Architecture, from Orcadesign Consultants Sdn Bhd, and from the Innovative Design Center of Lenevo in Beijing. The criteria for final product model selections were based on Langrish’s (1993) case study selection schemes, namely: comparative, representative, best practice (referring to those that received high exposure in the media and good professional reviews), and the ones next door (mainstream selections). The reason for inviting professional designers to evaluate the stimuli was that they have similar ideas when it comes to professional understanding of product properties and, when given the same criteria, tend to control their selections more objectively. The panel’s choices were decided by combining theoretical insights with information drawn from the choices made by the respondents in the initial selection study.

Figure 1. Final selection of mobile phones: Top row, left to right, choices 1 to 5: Siemens Xelibri 6, Handspring Palm Treo 700p, Motorola Pebl, LG L1150, Nokia 6600. Bottom row, left to right, choices 6-10: Motorola Razr v3c, Nokia 3250, Nokia 7610, Motorola V70, KDDI Talby.

Figure 2. Final selection of MP3 players: Top row, left to right, choices 1-5: Rio Chiba, iPod, Lyra RD 1076, iClick DAP7.0, iRiver H10. Bottom row, left to right, choices 6-10: Rio Carbon, Sony NW-E 400 & 500 series, Sony Psyc Network Walkman, S2 Sports Network Walkman, Lyra Sport.

Figure 3. Final selection of fragrance bottles: Top row, left to right, choices 1-5: J’Adore by Dior, Le Feu D’Issey Light by Issey Miyake, JPG Classique for Women, Marc Jacobs Blush, Flower by Kenzo. Bottom row, left to right, choices 6-10: Hugo Boss Intense Fragrance for Women, DKNY Be Delicious, Tresor by Lancome, JPG Classique for Men, Estee Lauder Beyond Paradise.

Collection & Analysis of Data

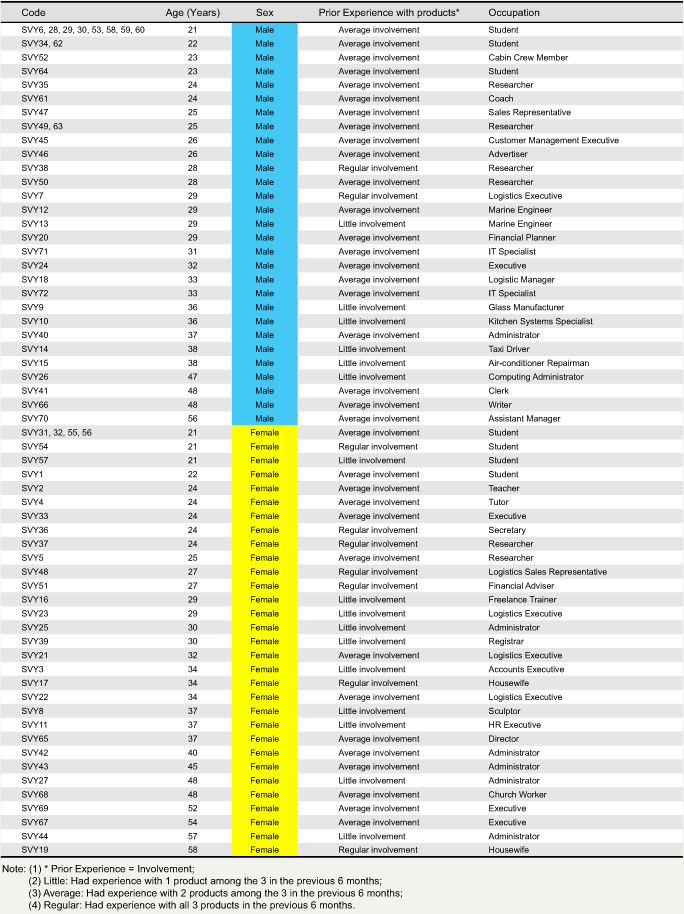

A mixed methodology of descriptive and qualitative methods was adapted for this study. Interviews were conducted on a one-to-one basis, using a semi-structured questionnaire, with voluntary participants at the university and at a community center (Drucker, 1954; Brennan, 1995, Neuman, 1997). In total, 72 participants (38 male and 34 female), from 21 to 58 years of age (with an average age of 31 years), responded to the questionnaire. Detailed profiles of the participants are shown in Appendix 1.

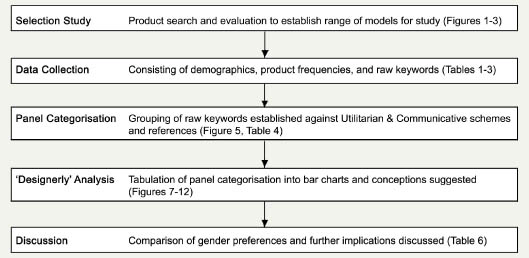

Having the researcher stationed nearby the participants was advantageous in this situation as there could be someone available (optionally) and capable to answer any queries. As this study was conducted in Singapore, which has a multi-racial society, a clear advantage was to be found in having someone available to offer explanations of the questions in different languages or even dialects if the participant needed some sort of clarification. There was no interference with the participants’ answering of the questions besides the necessary translations. Although the possibility of influence was present, it should be very insignificant as the questions asked were not sensitive. Participants were shown black and white photographs of the product models, asked how regularly they came into contact with these types of products, asked to rank their choices from best-liked to least-liked from among the models, and allowed to freely suggest other models available on the market that they might feel more attracted to than the ones shown. They were also asked to suggest a keyword to describe their best-liked and least-liked choices of product model under each category. Other opinions and perceptions about owning these products were also gathered, with the aim of this step being to gain any unexpected insights into what features were generally attractive to men versus women. Figure 4 shows the research methodology used for this study.

Figure 4. Research methodology used in the study.

Methods Used for Panel Categorization

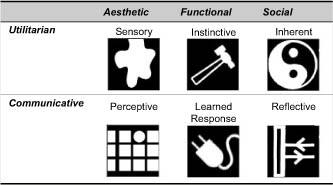

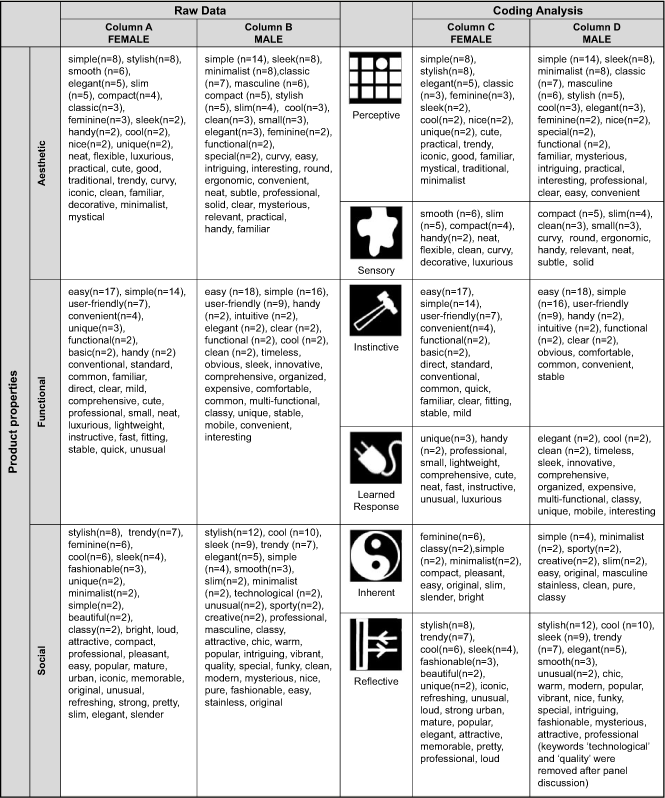

The information provided by the participants (e.g., the keyword collection) could be very useful as a reference for the final selection of a design from possible alternatives, as descriptive words can also have marked effects upon user perception. Although the qualitative data gathered may be seen as a sample of exploratory insight, or as a rather subjective exercise without pretensions to highly reliable statistical significance, by conducting first-level evaluation of the results collected, the resulting categorizations were illuminating. These categorizations represent an attempt to show the variety of keywords and to compare the differences in keywords that were suggested by the genders for the three types of products. Before proposing a set of constitutive dimensions for testing, there is a need to determine which keywords (or which groups of keywords) could be structured in accordance with the same underlying schemes. To this end, the analysis of the products is discussed with reference to two schemes: the utilitarian manifestation scheme and the communicative manifestation scheme (see Figure 5). The utilitarian scheme makes use of intuitive responses, whereas the communicative scheme makes use of learned responses. Although the variety of approaches that can be used for evaluating a product are many, each using different terminologies, these two schemes are regarded as "basic" (Gotzsch, 2003) and can be found to be agreed upon extensively in a review of the literature (Muller & Pasman, 1996; Lenau & Boelskifte, 2005). The product properties identified earlier (i.e., aesthetic, functional, social) are presumed to be highly relevant with regard to these two schemes.

Figure 5. Product properties as defined within utilitarian and communicative manifestations

(source: adapted from Muller & Pasman, 1996; Lenau & Boelskifte, 2005).

To make it easier to communicate within this paper, and within the utilitarian scheme, three sub-categories relating to the three product properties have been chosen: sensory, instinctive, and inherent (Muller & Pasman, 1996; Lenau & Boelskifte, 2005). Similar to the utilitarian scheme, the communicative scheme is helpful for understanding some of the metaphors in the analysis of keywords collected. The communicative scheme is divided into three sub-categories in relation to the three product properties: perceptive, learned response, and reflective. However, in proposing to use these two schemes, it does not obscure the fact that additional expressions might occur in relation to historical contexts or cultural conventions (Van Rompay, Hekkert, Saakes, & Russo, 2005), and thus it may be necessary for the expressions used in these schemes to be considered subject to change.

Analysis, Results & Discussion

Aesthetic, Function and Social Representation Identified

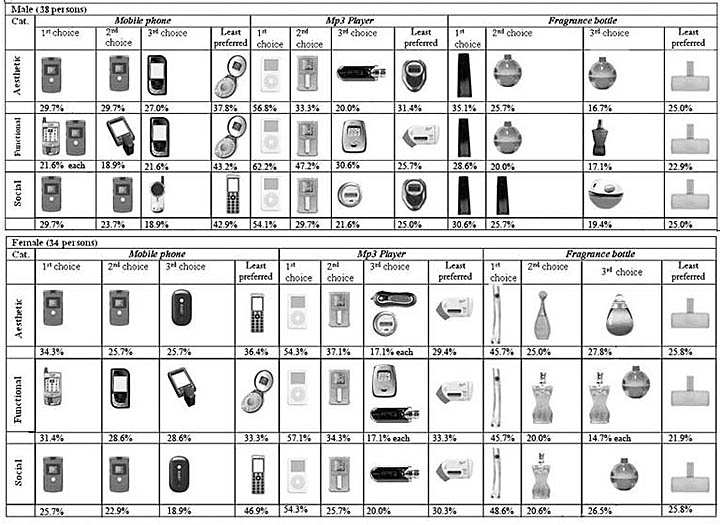

From the initial ranking results, the best- and least-liked choices of products selected by both genders were not exceptionally different (refer to Table 1). From the frequencies in choices of fragrance bottle design, it was revealed that female choices of non-functional form revolved mostly around less geometrical shapes; for example, the unanimously repeated selection of choice 5 (Flower by Kenzo) and choice 3 (JPG Classique for Women) among the fragrance bottle designs, truly reflected a great extent of interest among women in organic forms and familiar themes of femininity, nature, plant life and fluidity. In contrast, the selections of males tended to be those of more regular and geometric form. These results coincided with existing published literature (Moss, 1999) on women’s aesthetic preferences. From the top few selections of both genders’ best-liked mp3 players, choice 2 (iPod) and choice 5 (iRiver H10), as well as choice 6 among the mobile phones (Motorola Razr v3c), it could be safely assumed that most of the men were concerned with interface controls that are both manageable and technologically intriguing at the same time. However, from ranking results based on percentage frequencies, it is difficult to reveal true gender differences pertaining to issues of functionality. A summary of the two genders’ choices of designs is shown in Table 1. The choices of product models may seem unconvincing as evidence of true gender-based preferences. Therefore, it is important to gather some analysis from other indicator(s), these being the keywords in this pilot study; to gain more accurate insights into different gender tastes and preferences.

Table 1. Summary of most- and least-preferred choices of products by the genders

Collection of Raw Keywords

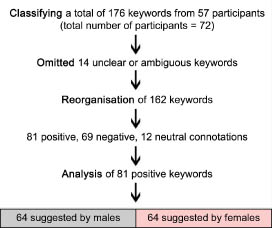

A total of 162 different keywords (81 positively inclined, 69 negatively inclined, and 12 neutral in meaning) were generated from the valid responses (from 57 participants, 30 male and 27 female). Figure 6 shows the collection workflow of the keywords. Some of these keywords were commonly used in describing the most- and least-preferred choices of products. Some unclear or ambiguous keywords suggested in the interview sessions were omitted in the compilation process.

Figure 6. Process used in collection and coding analysis of keywords.

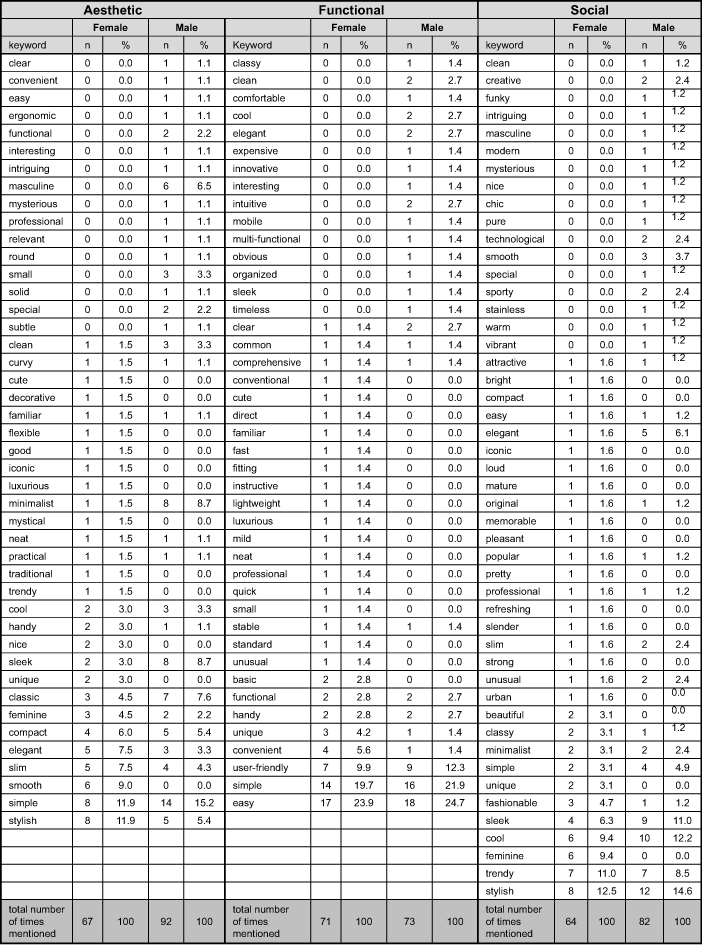

Some of the keywords (e.g., simple, sleek, feminine, elegant, minimalist) were constantly repeated in describing choices related to all three properties. Generally, it was observed onsite that some keywords (e.g., good, technological, etc.) may be generated by almost instantaneous, pre-attentive judgments without careful deliberation, apparently not based on any attentive consideration of the product’s component parts; furthermore, whether positively or negatively inclined, some of these words have the same meaning. Since there were no definite rules for the choices of terms, ideally, a final keyword collection for further study should be orientated towards characteristics that would need to be taken into consideration for a future gender-oriented design. These keywords are indeed popular attributes used by people to describe what they see or feel when using products. Dictionaries (The Collins English Dictionary, Updated Edition, and the Collaborative International Dictionary of English v0.48) and thesauruses (The Moby Thesaurus II by Grady Ward, 10, and Roget’s 21st Century Thesaurus) were used to check all 162 individual raw keywords prior to starting the tabulation process. Table 2 shows all of the raw keywords collected and lists them directly according to the three product properties, as suggested by the participants. Their frequencies and percentages have also been calculated and presented. No amendments have been made to this tabulation of raw data at this point in the study. Despite the fact that some keywords, such as luxurious, appeared in both the Aesthetic and Functional categories, they were actually suggested by different participants (SVY8 and SVY21, respectively). This may go to show that in terms of its message, a keyword can be multi-layered: it can contain a denotative level, which objectively describes the item, as well as a connotative level, which refers to the field of association with regard to its appearance.

Table 2. Collection of positively inclined raw keywords

Evaluation by Review Panel

Both genders suggested 64 positive keywords each, resulting in 81 different words. These were reorganized accordingly, depending on their repetition and on overlapping meanings (see Figure 6). Subsequently, the coding analysis procedure was conducted using a four-person review panel (2 males, 2 females, all non-designers) in order to assess how the raw keywords related to the matching scheme references with regard to gender orientation and to determine the underlying reasons provided for such judgments. A common understanding with regard to the scheme references (Figure 5) was established for the review panel before the coding analysis procedure was undertaken. Some keywords were debated, while others were decided by compromise where to be placed among the utilitarian and communicative scheme categories (e.g., luxurious was placed under the perceptive or sensory reference category), and two of them were removed after the discussion (i.e., technological and quality). The following is a discussion of how and why various keywords were categorized or coded according to the various references of the two schemes.

The sensory reference is related to associations that refer to the cultural context of a user or to geometrical elements such as shapes and lines in its design that create affection for the product. Expressions such as decorative, compact, slim and luxurious that are most likely related to the proportion or texture details of a product are included under the sensory reference. The instinctive reference relates to physical and primary characteristics that may include specific descriptions related to handling and operation of the product. Based on these considerations, one may propose that expressions related to ease of use, such as easy and convenient, and expressions such as user-friendly, handy and simple, are structured by the instinctive reference. The inherent reference relates to the basic nature of the user. Keywords indicating stereotypical gender role descriptors such as feminine being equated with warm and masculine with original would express the inherent reference.

The perceptive reference relates to expressions that indicate the wish of a user to be part of a group or, on the contrary, to be seen as different from others. Expressions reflecting a sense of affiliation, such as stylish, trendy, fashionable, and beautiful, are presumably related to the perceptive reference. The learned response reference relates to the product’s intrinsic qualities, such as its working principles, quality, and newness, which may require some learning procedure or effort. Expressions such as multi-functional, innovative, instructive, and unique are structured by this reference. The reflective reference relates to qualities that the user aspires to be perceived as possessing by others. This would include expressions reflecting a sense of inspirational goals, such as beautiful, cool, modern, or chic. The six references discussed are in some senses opposite and in some senses strongly related. With regard to their differentiated positions, they each relate to instances when notions of irrationality versus radical thinking are focused upon.

Table 3 shows the outcome of the evaluative discussion by the review panel. The raw keywords are listed in Columns A and B, while the keywords as categorized after the discussion are tabulated in Columns C and D.

Table 3. Coding analysis of keywords by schemes

Discussion based on ‘Designerly’ Analysis

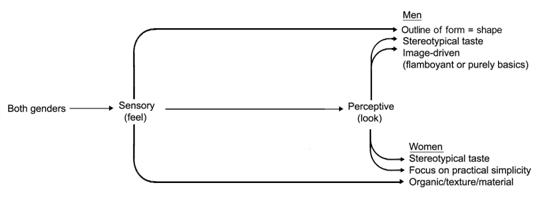

Figure 7 demonstrates that men seem concerned with characteristics such as compactness, slimness, and cleanliness. They suggested keywords such as solid, ergonomic, and relevant, ones that women did not mention at all. This may suggest men’s preference for products that look sophisticated and reliable, with an emphasis on overall structure. Women on the other hand seem to be especially concerned with smoothness, slimness, and compactness. Along with words such as curvy, flexible, decorative, luxurious, and neat, this tends to show their preference toward organic forms, texture-based details and materials. The basis of this type of keyword linkage and identification is based on synonymy. In the figurative sense, words are termed to be synonymous if they have the same connotation. A thesaurus search can offer the researcher a listing of similar or related words; these are often, but not always, synonyms. This compaction of similar conception among keywords (indicated by highlighting) is also represented in Figures 8 to 12.

Figure 7. Aesthetic – Sensory.

Figure 8 shows that both genders place much emphasis on simplicity when it comes to perceived aesthetic. Other than that, women seem concerned with products being stylish, followed by elegant and feminine. Women think that it is important for things to be feminine-looking. On the other hand, through expressions such as masculine and classy, minimalist and sleek, men may seem to regard aesthetic qualities as something that should be more manly or image-driven (this could be either extreme, e.g., flamboyant or purely basic). However, they also reveal an interest in provocative characteristics (interesting, intriguing, mysterious, and professional). Men also suggested themes such as functionality, ease of use, convenience, and clarity. Likewise, women also suggested keywords such as traditional, mystical, and cute, which may associate their taste with known stereotypical classifications.

Figure 8. Aesthetic – Perceptive.

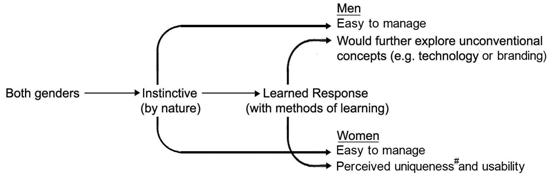

Figure 9 shows that both genders take into consideration similar instinctive functionalities. Both genders seem to be concerned with issues such as ease of use, simplicity, and user-friendliness. Clearly, when asked about functionality, people desire to handle something using direct methods, meaning that ease of use relates to a product being regarded as pleasurable.

Figure 9. Functional – Instinctive.

Interestingly, as can be seen in Figure 10, men seem to be more concerned with image-driven factors within the functional product property, suggesting themes such as elegance and coolness. At other times, they may still suggest technologically driven factors with keywords such as multi-functional, innovative, and mobile. They also suggested cost-driven factors within the considerations of function (e.g., expensive). Women are more concerned with issues such as handiness and instructiveness, probably due to the fact that, semantically, they are concerned with the form of the product (other keywords that came up are small, neat, lightweight, and cute). Both genders regard that functionality should be accompanied by some special element (e.g., uniqueness), probably because in today’s society, in which technological innovations are changing very rapidly, people are constantly exposed to new inventions and interesting new gimmicks. They have unknowingly increased the concept of their demands for functional characteristics, expecting functionality to be apparent at a pragmatic level as well as at a level that includes novelty.

Figure 10. Functional – Learned Response.

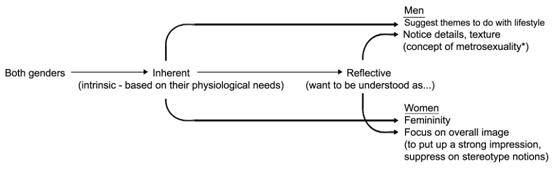

Figure 11 shows that both genders seem to value characteristics such as simplicity, minimalism, ease of use, and originality. As expected, women are drawn to a female-related image, as seen by their tendency to suggest words such as elegant, slender, and pleasant, while valuing femininity. Interestingly, men displayed an intrinsic interest in themes that relate to lifestyles and aesthetic appeal by suggesting keywords such as creative, sporty, stainless, clean, and pure.

Figure 11. Social – Inherent.

Figure 12 shows that both genders seem to share some image-driven expressions such as sleek, stylish, trendy, fashionable, and cool in describing their opinions related to the positive social affiliation of a product. Differences appear, however, in two circumstances, (1) when women suggested words such as unique and iconic, while men suggested words such as mysterious, elegant, and intriguing, and (2) when men suggested words such as smooth and classy, which relate more to tactile features that add to their concept of being socially reflective. This displays a very interesting insight into what the genders are trying to relate, supported by evidence that no one can be completely stereotyped; there are always some cross-gender interests (Basow, 1992). Although gender stereotypes appear to have considerable generality and to be quite firmly grounded by psychological and gender research, some indication exists that people’s attitudes about socially desirable traits for men and women may be changing, albeit slowly, in response to cultural changes (Ruble, 1983; Lewin & Tragos, 1987).

Figure 12. Social – Reflective.

Men and women are without a doubt continuing to expand the boundaries of acceptable interests and styles within their typical gender roles. Men and women differ in the way they are becoming visually, functionally, and socially literate (Barker & Parr, 1992). Women’s experience of modernity is indubitably different from that of men (Sparke, 1995). It may not be fair to generalize that women do not wish to own products with characteristics such as exclusivity, individuality, and preciseness. From this study, it can be seen that both genders appreciate ease of use in a product (refer to Figure 9) and that women focused on form over function as evidenced through certain keywords, alternatively suggesting that they may be willing to learn how to handle a product later if at first they feel that it looks good (refer to Figure 10). On the other hand, men focused on functionality, and also image-driven factors established by iconicity, while including an interest in technological advancements.

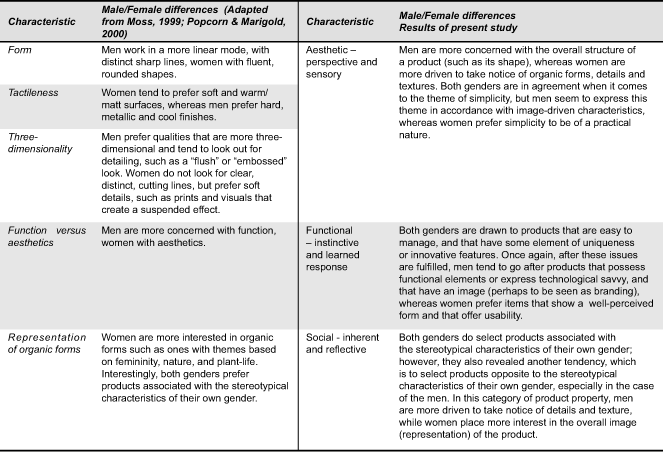

The results indeed have similar and different pointers compared with past research, as shown in Table 4. However, these results can be transferred to future research as "benchmark-measures" that may be useful for developing mock-ups for gender-based designs. A global understanding that keeps these references in mind would further enhance existing design methodologies, but by proposing them, it does not mean that product designing is reduced to a prescriptive or creatively constrained activity. Figures 13 to 15 show schematic representations of the current findings.

Gender may be socially constructed; therefore, the outcome of this research may be transferable but can not necessarily be generalized for every situation. Even as product trends vary over regions and as consumer needs vary over time, the results of this study as well as those of a similar nature in terms of gender orientation are crucial for helping companies to position products for different segments of the market in the future.

Table 4. Comparison between findings of past research and this pilot study

Figure 13. Schematic representation of aesthetic key points for the two genders.

# The uniqueness aspect here tends toward intangible aspects such as luxury and cuteness.

Figure 14. Schematic representation of functional key points for the two genders.

*For this study, the term “metrosexuality” is viewed as representative of the embracing of

relational understanding in addition to its lifestyle and aesthetic implications.

Figure 15. Schematic representation of social key points for the two genders.

Methodological Limitations

Although the difference between the numbers of male versus female participants was as low as 5.6%, more studies using groups from the rest of the population should be studied, at an equal ratio, especially due to the strong potential influence of gender differences in the success of products on the market. With an exploratory approach in mind, this study attempted to identify the differences between the preferences of males and females with a global perspective. Previous studies have shown that young people, such as students, as demonstrated in product preferences research, focus more on emotional responses, whereas older people tend to focus more on satisfaction (Campbell & Converse, 1976). Hence, it is reasonable to assume that older people would feel differently about product properties compared to younger working professionals. A comparison considering differences in age would therefore be recommended. In addition, we cannot exclude the possibility that the personal and intellectual bias of the research team may have shaped the data. This has been minimized by making the account as reflexive as possible, by conducting selection-testing sessions with non-designers and designers, and then by subsequently reporting a range of different perspectives only by non-designers. Due to the fact that this study was conducted in a diverse multi-ethnic society such as Singapore, issues relating to any particular cultural origin of the participants did not emerge as a theme in the data collected. However, there should be more testing in relation to different cultural settings, as this may alter the perceptions toward product properties. If this study should be continued with further comparisons of existing consumer products among the genders, the sample size could be increased so as to collect data from a more varied population. Interviews could be enhanced to record more first-hand information for deeper analysis of gender tastes and preferences. Products could be presented through three-dimensional means in later user trials, as two-dimensional visualizations may not truly illustrate utilitarian and technical characteristics in some instances.

We should also issue a word of caution that there may still be a lack of real and deep understanding of the true context of the participants’ choices for the representative words. It is not clear whether the participants thought all these keywords could truly fit to give a comprehensive description of the products shown. For example, the illusion of the keyword simple, "whereby one mistakenly judges something to be simple only because it is familiar" can happen due to a tendency of over imputation (Nickerson, 1999). Hence, for future research in the keyword collection process, participants could also be provided a relatively large set of keywords to distribute over the categories of product choices available, ranging over the product properties in consideration. Ambiguous and unfamiliar words may be distinguished from those that are both clear and unambiguous (neutrally defined) by the use of a numeric criterion (Desmet, 2002). This criterion could be defined on the basis of the assumption that a keyword that is clear and unambiguous is indicated by an octant frequency that is significantly higher than chance level (because the distribution resembles a normal distribution). Alternatively to such a pilot study could be in-depth interviews for the purpose of collecting keywords from a small number of participants and applying the induction approach to data analysis. Last but not least, there might also be queries about the exact usefulness of relating such discoveries of gender differences to existing product design development processes, probably due to the specifications of different objects and different cultures – with regard to utility and social significance. This suggests the need to consider future implications to test out the feasibility and usability of the proposed method.

Future Implications & Conclusion

The opinions and preferences from the genders collected in this pilot study can serve as a starting point for future experimental studies. The next such study could be a population-based study, and later studies might be undertaken to design specific applications, for example, for a female-oriented healthcare product that elicits attributes such as femininity, assurance, and high-quality personalized healthcare for women. Meininger (1986) conducted a study on "sex differences in factors associated with the use of medical care and alternative illness behavior," and the results provided some insight into how males and females differ in their tendency to respond to their symptoms when it comes to self-treatment, lay consultation and medical care. Women differ in terms of the operation, perception and understanding of medical devices (Ward & Sanson-Fisher, 1996). Given the fact that the experience of illnesses and medical conditions can be institutional, clinical, cold and even painful for the individual, the procedure would be to translate the key essences discovered from this stage, to the product conceptualization stage, where development could be undertaken to create the details that could enhance healthcare device design. Comparative studies could be carried out by asking participants to compare the new products designed for women with existing healthcare devices after applying the references to women’s healthcare device design to assess if the new device design indeed elicits the intended attributes. In this respect, the same identification process could be applied for designing male-oriented products. From theoretical materials and from the results of this research, the importance of future developments in gender-oriented products seems irrefutable.

The concept of a well-defined, gender-oriented product characteristic remains difficult to grasp, as there is no complete theory that embraces all the different aspects and the complexity related to such a concept. It is evident that careful attention needs to be given to the selection of applied associations in order to avoid domains with strong masculine or feminine overtones. Setting up two opposite and distinct lists of traits for female and male designs would be entirely inappropriate and misleading. However, if a design problem is to be framed gender-neutral, then some important gender considerations with regard to the perceptions of the product and task would be neglected. Rather than distributing designs in an all-or-none categorization, this approach needs to be modified. Specific people interact in specific situations and produce specific behaviors in relation to different product properties that they come into contact with. If products are read based on designers’ interpretations, the product language that would be interpreted would most likely be of a sensorial perception that would be highly subjective, probably due to their expertise and affiliation. Hence, there is a need to conceive a method to systemize the way products are perceived and especially the way their functional attributes are defined, in order to reach a common basis for communication and understanding. One neutral method would be to collect the views of non-designers. The results of this research have revealed female-oriented themes that should motivate product semiologists, sociologists, and design researchers to enlarge their views of pleasurable product design attributes and language for the genders. Having an overview of the aspects that can add potential value to a product’s design could facilitate the creation of a successful new product and bring its design as close as possible to the user’s desired expectations and needs.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of a research project supported by a grant (WBS number: R-295-000-055-112) provided by the School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore. Special mention should be made of three designers who contributed valuable insights into the exploratory stage of this study: Dr Christian G. Boucharenc, Assistant Professor, NUS Department of Architecture; Mr. Chang Shian Wei, Industrial Designer, Orcadesign Consultants Sdn Bhd; and Mr. Winston Chai, Industrial Designer, Innovation Design Center, Lenovo, Beijing, China. Special thanks also to the four-person review panel that contributed their time to this study and who have expressed a wish to remain anonymous.

References

- Alreck, P. (1999). Commentary: A new formula for gendering products and brands. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 3(1), 6-18.

- Basow, S. A. (1992). Gender: Stereotypes and roles (3rd ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Barker, N., & Parr, M. (1992). Signs of the times: A portrait of the nation’s tastes. Manchester: Cornerhouse.

- Baxter, M. (1995). Product design – A practical guide to systematic methods of new product development. London: Chapman & Hall.

- Brennan, R. (Ed.). (1995). Cases in marketing management. London: Pitman.

- Bürdek, B. (1996). Design: Geschiedenis, theorie en praktihk van de produktontwikkeling. Den Haag: Ten Hagen & Stam.

- Campbell, A., & Converse, P. E. (1976). The quality of American life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Carlton, J. (1997). Apple: The inside story of intrigue, egomania and business blunders. New York: Time Business/Random House.

- Cho, H. S., & Lee, J. (2005). Development of a macroscopic model on recent fashion trends on the basis of consumer emotion. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 29(1), 17-33.

- Crossley, L. (2003). Building emotions in design. The Design Journal, 6(3), 35.

- Crozier, R. (1994). Manufactured pleasures – Psychological responses to design. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- De Angeli, A., Lynch, P., & Johnson, I. (2002). Pleasure versus efficiency in user interfaces: Towards an involvement framework. In W. S. Green & P. W. Jordon (Eds.), Pleasure with products, beyond usability (pp. 97-112). London: Taylor & Francis.

- Desmet, P. M. A. (2002). Designing emotions. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, TU Delft, Delft, The Netherlands.

- Desmet, P. M. A., & Hekkert, P. (2002). The basis of product emotions. In W. S. Green & P. W. Jordon (Eds.), Pleasure with products, beyond usability (pp. 61-68). London: Taylor & Francis.

- Dexter, A. (2002). Egotists, idealists and corporate animals – Segmenting business markets. International Journal of Market Research, 44(1), 31-52.

- Drucker, P. F. (1954). The practice of marketing. New York: Harper & Row.

- Forty, A. (1986). Objects of desire, design and society 1750 – 1980. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Gotzsch, J. (2003). Managing product expression: Identifying conditions and methods for the creation of meaningful consumer home products. Unpublished doctoral dissertation of Business Administration, Henley Management College, Brunel University, London, UK.

- Handcellphone.com (n.d.). Gadget for baby – BabyMo cellular phone. Retrieved December 26, 2006, from http://www.handcellphone.com/archives/gadget-for-baby-babymo-cellular-phone.

- Janlert, L., & Stolterman, E. (1997). The character of things. Design Studies, 18(3), 297-314.

- Jordon, P. (1998). Human factors for pleasure in product use. Applied Ergonomics, 29(1), 25-33.

- Jordon, P. (2000). Designing pleasurable products. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Langrish, J. (1993). Case studies as a biological research process. Design Studies, 14(4), 357-364.

- Lenau, T., & Boelskifte, P. (2005). Product search through the use of semantic properties. In Y. Levanto, P. Sivenius, & S. Vihma (Eds.), Design communication (UIAH Working Paper, Vol. F30, pp. 11-23). Helsinki: University of Art and Design Helsinki.

- Lewin, M., & Tragos, L. M. (1987). Has the feminist

movement influenced adolescent sex role attitudes? A reassessment after a quarter century. Sex Roles, 16(3-4), 125-135. - McDonagh-Philp, D., & Lebbon, C. (2000). The emotional domain in product design. The Design Journal, 3(1), 31-43.

- McDonagh, D., Bruseberg, A., & Haslam, C. (2002). Visual product evaluation: Exploring users’ emotional relationships with products. Applied Ergonomics, 33(3), 231-240.

- McKenna, R. (1988, Sep/Oct). Marketing in the age of diversity. Harvard Business Review, 66(5), 88-95.

- Meininger, J. C. (1986). Sex differences in factors associated with use of medical care and alternative illness behaviours. Social Science and Medicine, 22(3), 285-292.

- Morello, A. (1995). Discovering design means [re-] discovering users and projects. In R. Buchanan & V. Margolin (Eds.), Discovering design: Explorations in design studies (pp. 69-76). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Moss, G. (1999). Gender and consumer behaviour: Further explorations. Journal of Brand Management, 7(2), 88-100.

- Muller, W., & Pasman, G. (1996). Typology and the organization of design knowledge. Design Studies, 17(2), 111-113.

- Neuman, W. L. (1997). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Nickerson, R. S. (1999). How we know – and sometimes misjudge – what others know: Imputing one’s own knowledge to others. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 737-759.

- Ortony, A., Clore, G. L., & Collins, A. (1988). The cognitive structure of emotions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Popcorn, F., & Marigold, L. (2000). EVEolution: The eight truths of marketing to women. New York: Hyperion.

- Ruble, T. L. (1983). Sex stereotypes: Issues of change in the 1970s. Sex Roles, 9(3), 397-402.

- Schiffman, L. G., & Kanuk, L. L. (1994). Consumer behaviour (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Sparke, P. (1995). As long as it’s pink: The sexual politics of taste. London: Pandora Press.

- Van Rompay, T., Hekkert, P., Saakes, D., & Russo, B. (2005). Grounding abstract object characteristics in embodied interactions. Acta Psychologica, 119(3), 315-351.

- Ward, J. E., & Sanson-Fisher, R. W. (1996). Accuracy of patient recall of opportunistic smoking cessation advice in general practice. Tobacco Control, 5(2), 110-113.

Appendix 1: Detailed Information of Participants