Enabling Relational Adaptation: Flipping the Script in Public Service Design

Audun Formo Hay 1,* , Josina Vink 1, and Daniela Sangiorgi 2

1 Oslo School of Architecture and Design, Oslo, Norway

2 Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy

Pre-scripting service interactions has traditionally been central to designing, managing, and scaling public services. While scripts help actors coordinate, predefined scripts can lock actors into ways of relating that are inappropriate for their specific situation. In response, there are growing calls to design public service systems in ways that allow actors to adapt their relations based on what is meaningful to them. This research outlines design principles for enabling actors to continuously shape service systems from within through an ongoing, collective, and intentional process of re-scripting their relations. The principles were developed through an 18-month research-by-design study within Norwegian child welfare involving over 900 system actors. Informed by relational theory, we propose that relational adaptation in public service systems can be enabled by: (1) promoting the co-authorship of scripts, (2) facilitating ongoing script revision, (3) supporting the navigation of relational tensions, (4) aiding the unwriting and rewriting of scripts, and (5) stewarding the negotiation of meaning across relations. Combined, these principles suggest an approach to public service design that fosters ongoing, bottom-up transformation based on what affected actors consider meaningful. The design principles contribute to reconceptualizing service scripts, delineating a novel approach to service system transformation, and advancing a relational ontology for public service design.

Keywords – Service Scripts, Relational Adaptation, Service Design, Public Service, Relational Design, Service System Transformation.

Relevance to Design Practice – This article offers design principles to guide practitioners in enabling ongoing adaptation within public service systems. By demonstrating these principles with concrete examples, this research outlines an actionable role for designers in supporting transformation in public service systems, enabling actors to design and shape these systems from within.

Citation: Hay, A. F., Vink, J., Sangiorgi, D. (2024). Enabling relational adaptation: Flipping the script in public service design. International Journal of Design, 18(3), 9-27. https://doi.org/10.57698/v18i3.02

Received June 15, 2024; Accepted October 30, 2024; Published December 31, 2024.

Copyright: © 2024 Hay, Vink, & Sangiorgi. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: audun.formo.hay@aho.no

Audun Formo Hay is a community psychologist and Ph.D. fellow at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design, researching on how to design more adaptive and dignified public service systems. Before his PhD, he worked for eight years with systemic therapy, supporting marginalized families within Norway’s child welfare system as both a therapist and a leader. Audun teaches and supervises systemic practices across fields such as design, psychology, psychiatry, and social work.

Josina Vink is an associate professor of Service Design at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design. Their research and teaching focus on shaping social systems, particularly related to health and care. Prior to being in academia, Josina worked for a decade as a service and systemic designer in healthcare.

Daniela Sangiorgi is a full professor of Design and head of the Master program in Product Service System Design at Politecnico di Milano. She worked for 8 years at ImaginationLancaster at Lancaster University. She has published seminal work in service design, contributing to the development of the field. Her research interests are in design for service innovation, with a focus on transforming the public sector and healthcare systems. Her recent research has been centred on developing a collaborative and systemic approach to designing for young people’s and adults’ mental health and well-being.

Introduction

“We know a lot about trauma and can offer a good program to help you,” the young therapist said, sitting opposite a man in his fifties. Once a person of high rank in his homeland, the client now suffered from the violence he had fled. The therapist, adhering to his professional script, had carefully assessed the client’s symptoms and offered a well-proven trauma therapy.

After a pause, the client responded, “You might know a lot from your books and routines, but there are also lessons I can teach you.” Although the client smiled, the therapist felt uneasy. Was his competence in question? Or the program’s effectiveness? The client continued, “the first lesson is about how demeaning it can be for someone like me to need help from someone like you.”

Standardizing relations among actors has been vital in designing, managing, and scaling public services (Pedersen & Pors, 2023; Soss et al., 2011; Brodkin, 2006; Fotaki, 2011). This standardization typically involves pre-defining service scripts, which outline the specific tasks and actions that service providers should perform during their interactions with service users (Harris et al., 2003; Victorino et al., 2013). However, pre-scripting relations can also undermine dignity, as highlighted by the client in the vignette above. This story is directly drawn from an early interaction of the first author when working as a therapist in child welfare. It illustrates how dignity can be compromised when pre-scripted ways of relating are enacted despite being inappropriate to those involved. In response, there are growing calls to transform relations in public service systems from being pre-scripted to becoming more adaptable (Cottam, 2011; Storch & Hornstrup, 2020; Donati, 2015a). Under banners like collaborative governance, relational welfare, and collaborative innovation, scholars argue that actors in public service systems should be able to shape their relations based on what is meaningful to them, rather than being confined to ways of relating imposed by others external to the situation (Ansell & Gash, 2007; Torfing, 2019; Voets et al., 2021).

At the same time, public service systems are increasingly turning to service design to foster innovation (Kimbell & Bailey, 2017; Malmberg & Wetter-Edman, 2016; McGann et al., 2018). Scholars suggest that service design can support bottom-up transformation in service systems through human-centered, collaborative and action-oriented approaches (Anderson et al., 2018; Koskela-Huotari et al., 2021). However, service design practice has traditionally embraced the pre-scripting of service interactions by designers and managers to ensure service consistency and quality (Edvardsson & Olsson, 1996; Tax & Stuart, 1997). Popular service design tools, like the service blueprint, outline key activities and roles for service providers along a customer journey, reinforcing pre-defined, standardized interactions (Shostack, 1984). Thus, if traditional service design approaches are adopted within the public sector uncritically and without adaptation, there is a risk that service design may continue to lock actors into inflexible ways of relating that end up being inappropriate or unmeaningful to them.

Thus, an alternative approach to service design is needed to support actors in dynamically shaping their relations within public service systems. This approach would move away from pre-scripting and allow actors to adapt their relations together based on their evolving needs and meanings. Although scholars advocate for more situated, pluralistic approaches where actors design and shape service systems from within (Akama et al., 2023; Duan, 2023; Vink et al., 2021), practical design approaches for enabling actors to do so remain scarce, particularly in complex public sector settings where diverse interests and values coexist (Hay & Vink, 2023).

In response, this research aims to develop an actionable service design approach that enables actors within public service systems to continually adapt their relations by themselves instead of having these relations pre-scripted by others. To develop such an approach, we draw on relational perspectives from sociology and social constructionism to inform an 18-month programmatic research-by-design project (Brandt & Binder, 2007; Brandt et al., 2011) within the Norwegian child welfare service system. Given that welfare systems have received particular attention for needing transformation toward greater co-creation and human connection (Cottam, 2011; Selloni, 2017; Von Heimburg & Ness, 2021), this context serves as an relevant example, demonstrating a design response to the broader calls for increasing relational adaptability in public service systems.

To understand how design could support actors in adapting their relations by themselves within this context, we conducted three extensive design explorations involving over 900 system actors. The explorations included a series of experiments that used prototyping, a dialogue lab and an interactive theater production. Through this research, we abductively developed actionable principles, grounded in relational theory, for how design can enable relational adaptation among actors in public service systems. These principles contribute to: (1) reconceptualizing service scripts from a relational perspective, (2) delineating relational adaptation as a novel approach to stewarding service system transformation, and (3) advancing a relational ontology for public service design.

We begin this paper by reviewing the traditional role of pre-scripting in service design and public management, before outlining the current calls for better enabling actors to participate in shaping the service systems they are embedded within. We then draw on sociology and social constructionism to delineate a relational perspective on how scripts can be understood to be continuously negotiated among actors. Next, we detail our research methodology and outline the findings through five design principles, each with a conceptual underpinning informed by relational theory and demonstrative practice examples. We conclude by discussing the implications of these design principles for research and practice in public service design, along with related areas for future research.

Theoretical Background

Pre-scripting Interactions in Public Service Design

In the 1970s, the public sector faced criticism for becoming an increasingly expensive and paternalistic bureaucracy that disempowered citizens (Diefenbach, 2009; Torfing et al., 2019). In response, New Public Management emerged in Western countries and spread worldwide, aiming to reform the public sector from a legal authority to a service provider (Gruening, 2001; Hood, 1991). Using a market-based approach to public administration, the reform promised to reduce costs while enhancing user satisfaction with public services (Diefenbach, 2009; Osborne et al., 2013). Performance, measured by efficiency and customer-perceived quality, became a key criterion for evaluating public services (Callahan & Gilbert, 2005).

Service design has also been significantly influenced by a market-based logic (Akama et al., 2023), which has carried into applications in the public sector (Kimbell & Bailey, 2017). In the 1980s and 1990s, service design was prominently discussed within marketing literature as a means of improving customers’ perceived service quality to increase market value (Shostack, 1984). Here, service was viewed as sequences of events and activities among actors (Bitner et al., 1994). To ensure effectiveness, it was necessary to clarify and control roles and responsibilities within these sequences (Solomon et al., 1985).

The pre-scripting of service interactions was crucial for making services designable by someone external to the service interaction (Penin & Tonkinwise, 2009; Zomerdijk & Voss, 2010). It also helped to support the scaling of these services to build a competitive advantage for service firms (Nguyen et al., 2014; Victorino et al., 2013). Service scripts tend to equate service provision with a series of staged performances aimed at creating desirable customer experiences (Grove et al., 2004; Stuart & Tax, 2004). When developing tools and approaches to design these interactions, service design typically reinforced pre-scripting as a fundamental way to improve service quality (Edvardsson & Olsson, 1996; Tax & Stuart, 1997).

By pre-scripting the enactment of service performances, the aim was to ensure efficient service delivery and consistent user satisfaction. This aligned with the aims of New Public Management, which ushered in standardization to enable efficient, transactional exchanges between actors through clearly defined roles, such as producers, providers, and consumers (Osborne et al., 2013; Torfing et al., 2019). In public service systems, this approach has been supported by implementing training, guidelines, specializations and data systems to manage performance through measurement and optimization (Moynihan, 2013; Pedersen & Pors, 2023; Stringham, 2004).

Towards Collaborative Script Writing in Public Service Design

The legacy of pre-scripting service interactions in service design and public management has increasingly been problematized over the past decade (Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011; Penin, 2018; Sangiorgi & Prendiville, 2017; Torfing et al., 2019). In public management research, it is acknowledged that standardized scripts hamper the ability of public service systems to meet the diverse and rapidly evolving needs of residents (Torfing et al., 2019). Similarly, there are growing calls within service design discourse to understand design as an ongoing, situated process, enacted by affected actors as they shape the service systems they inhabit (Akama & Prendiville, 2013; Vink et al., 2021).

As an alternative to earlier bureaucratic and market-oriented forms of public service management, there are growing aspirations for more collaborative forms of governance and welfare (Voets et al., 2021). This shift stems from the realization that the transactional forms of service produced by New Public Management have failed to create public service systems that work better and cost less (Hood & Dixon, 2015; Osborne, 2018). Collaborative approaches to governance typically involve a mode of policy and service development in which multiple actors are directly engaged in and accountable for collective decision-making (Ansell & Gash, 2007; Torfing & Ansell, 2021). In welfare, this shift is often referred to as relational welfare (Cottam, 2011; Donati, 2015a; Von Heimburg & Ness, 2021), which repositions actors from individuals producing, providing or consuming service to collaborators enabling “good lives lived well” (Cottam, 2019, p. 197).

Recent service design approaches seek to move away from pre-scripting service interactions, focusing instead on building collective capabilities for improvisation and negotiation among actors (Penin & Tonkinwise, 2009; van Amstel, 2023). This aligns with efforts to support distributed agency among actors to shape service systems, such as cultivating co-design cultures (Aguirre Ulloa, 2020), creating infrastructures for bottom-up innovation (Selloni, 2017), and increasing actors’ reflexivity to reform social structures within service systems (Vink & Koskela-Huotari, 2022). Through such collective mobilization, actors within public service systems can be enabled to rewrite the scripts that guide their relations in order for the scripts to be meaningful to them. However, acknowledging that collective capabilities to shape service systems emerge from the joint interactions and interdependencies among actors, scholars in service design and the broader design discourse have emphasized the need for a deeper understanding of relationality (Cipolla & Manzini, 2009; Escobar et al., 2024; Nielsen & Bjerck, 2022; Udoewa & Gress, 2023).

The Relational Nature of Scripts in Public Service

Relational theories assert that people are not isolated entities but are co-constituted by relations (Dépelteau, 2018; Emirbayer, 1997). The roles, identities, and selves that people inhabit are shaped in relation to others (Gergen, 2009). For instance, individuals cannot become professionals, relatives, or even actors in isolation within public service systems. Such becomings and the actions that follow them are shaped by meanings shared through language and cultural practices within the system (Gergen, 2015; McNamee, 2012). In child welfare, for example, the meanings attributed to parenting or care shape the relations between social workers and families, influencing how support is provided and received. These meanings are reflected in the scripts actors expect each other to follow when interacting. From a relational perspective, scripts can thus be understood as shared constructions that actors use to coordinate within service systems in ways that co-create value. However, these scripts are also “written” through relational processes involving negotiation among actors within broader systems of meaning. A crucial issue for design is to understand how these negotiations occur and what enables or constrains interdependent actors in service systems from shaping their relations to be meaningful for them.

As actors are embedded within relations, a relational perspective challenges the view of capabilities as belonging to solitary, agentic individuals (Dépelteau, 2018). Instead of acting on systems as isolated agents, a relational perspective highlights how actors’ capability to evoke change is always situated and interdependent within the relational dynamics in which they are embedded (Burkitt, 2016). From this perspective, social systems, including public service systems, are not fixed or external to individuals; instead, they are constituted by recurring patterns in how actors relate and coordinate their interactions within a given context (Burkitt, 2016; Donati, 2015b). Consequently, adaptation and transformation of these systems hinge on actors’ entangled capabilities to continually renegotiate and rearrange the scripts guiding their relations.

Methodology

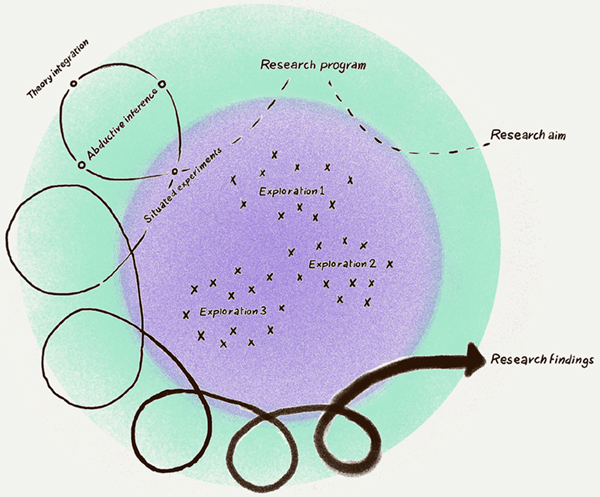

Over a year and a half, we engaged with the Norwegian child welfare system using a programmatic research by design approach (Brandt & Binder, 2007). This approach involves a research program, typically framed by a general aim and a situated question, with evolving learning gained by oscillating between design explorations and theory (Bang & Eriksen, 2014; Brandt et al., 2011). Our program aimed to develop an actionable approach for how service design can move beyond the pre-scripting of service interactions toward enabling actors within public service systems to continually adapt their relations themselves. Our situated question, derived from this aim, was: “How can service design enable actors in the Norwegian child welfare system to adapt their relations by themselves?”. Figure 1, inspired by Markussen and colleagues (2012), shows how our understanding was strengthened through recursive cycles of abduction throughout the research process. These cycles involved various situated experiments within three main explorations, collaborative inferences among participants, and integration with relational theory.

Figure 1. Design research program sketch. (Inspired by Markussen et al., 2012 & illustrated by Magnus Winther)

Throughout the research project, design practitioners and system actors collaborated to plan and conduct experiments, drawing inferences and integrating them with theoretical perspectives. We intentionally moved between different types of design experiments: Some were exploratory, aiming to challenge current practices in service design, while others were more pragmatic, aiming to foster immediate effects in the child welfare system. Comparing these experiments allowed us to examine actors’ capability to shape their relations across various situations and processes, and to explore different ways of designing for this capability (Fallman, 2008; Krogh et al., 2015).

Context and Participants

The research project was initiated by the management team of a large Norwegian child welfare organization in collaboration with the first author, an in-house design researcher. The child welfare organization, which funded the research together with the Research Council of Norway, wanted to develop better strategies to increase adaptability within child welfare to ensure dignified human encounters. While the primary aim of the Norwegian child welfare system is to support children, young people, and their families (Lov om Barnevern, 2023), child welfare agencies also have the legal responsibility to protect children and young people from harm, sometimes necessitating invasive actions like out-of-home placements. This co-existence of supportive and invasive interventions is often experienced by various system actors as contradictory and challenging (Bekaert et al., 2021; Kojan & Storhaug, 2021; Langsrud, 2017; Slettebø, 2008).

Approximately 130 social workers from the child welfare organization participated in the experimentation, with some directly leading and conducting research experiments. Additionally, other system actors, including representatives for children and young people, biological parents, foster families, professionals in auxiliary services like teachers, lawyers, and police, as well as politicians and bureaucrats, participated in various research experiments. In total, over 900 system actors were involved in the research process.

The first author led the research project, collaborating with 54 design practitioners in design experiments. This group of practitioners included 35 master’s degree students in design, six design teachers and researchers (including the first and second author), twelve graduate students in acting and scriptwriting, and a professional theater director. Given the sensitivity of the context, several steps were taken to support trauma-informed research and design approaches (Dietkus, 2022; Alessi & Kahn, 2022). First, protocols were established to ensure ethical engagement with participants, including transparent information about the research aims and activities, criteria for halting experiments if participants felt uncomfortable, and procedures for debriefs. These protocols were developed with input from relevant user organizations, including young people with lived experience in child welfare. Second, design students received guidance from child welfare professionals and trauma-informed design scholars to inform their practice. This included supervision from the first author, a licensed clinical psychologist with extensive child welfare experience, who led and supervised all research activities. Third, all participants provided informed consent, and the research complied with the General Data Protection Regulation, as assessed by the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research.

Project Process and Collected Empirical Material

The design experiments were conducted across three main explorations, which ran in parallel over one-and-a-half years. Table 1 outlines the aims, activities, participants, and empirical material gathered from the explorations, with each exploration consisting of a series of experiments.

Table 1. Overview of the aims and activities, participating partners, and empirical materials collected in each research explorations.

| Exploration aim | Exploration experiments | Collaborating participants | Documented material |

The Dialogue Lab: Designing dialogues in which social workers could collectively address dilemmas, struggles, and tensions they experienced in their relations. |

Weekly two-hour co-design sessions over one-and-a-half years in which a group of social workers engaged in collaborative inquiry. Prototyping and recursive development of reflexive dialogues. Various dialogue experiments involving social workers in the organization. Designing a structure for reflexive dialogue for all employees in the child welfare organization in bi-weekly one-and-a-half hour sessions. |

Nine social workers involved in the dialogue lab. Approximately 110 social workers involved in various experiments during the inquiry period. |

216 reflection notes written by social workers in the dialogue lab. Transcribed recordings of three focus group discussions among the participating social workers in the dialogue lab. Sketches, process photos and other materials from the research process. Various feedback and reflection notes from social workers in the child welfare organization participating in experiments. |

The Relational Drama in Child Welfare: Sparking reflexive conversations by enacting the emotional experiences that multiple system actors have in their relations within the system. |

Collaborative mapping and conversations about the child welfare system between system actors and design students. Six collaborative two-hour dialogue theater workshops that engaged various system actors in prototyping enactments of system relations. Design of an interactive theater event, including script, interactive engagement of participants, event flow, scenography, costumes, props, etc. Facilitating emerging conversations through interactive parts of the event and follow-up with the collaborating child welfare service. |

15 master’s degree systemic design students. 12 theater students, including actors and script writers, as well as a professional theater director. 70 system actors within child welfare were involved in the design of the interactive theater event. This included young people, parents, foster parents, social workers, managers, supervisors, bureaucrats, police, lawyers, and teachers. 800 participants visited the open interactive theater event, including people with lived experience, politicians, bureaucrats, and others related to the child welfare system. 130 social workers participated in an extended interactive theater event, including facilitated post-event conversations. |

77 reflection notes and eighth debrief discussions from students after collaborative mapping sessions. System maps and narratives developed in the experiments. Design materials from the event development including theater script, props, visual artifacts, notes, and sketches from the design process. Video recording of the full interactive theater event. 39 half-page reflection notes from participants in the interactive theater event. Transcribed 60-minute group conversations among 8-18 social workers, and participant observation reports from social workers attending these. Three-page individual reflection notes and a collective 200-page report from students written after the event. |

Designing for Dignified Child Welfare: Making child welfare more dignified for all actors by prototyping relational feedback loops. |

Eight weekly two-hour co-design workshops where social workers and design students conducted generative prototyping based on the social workers’ situated relations. Three three-hour co-design workshops involving external partner system actors. Exhibition of final prototypes involving approx. 50 participants who engaged in discussion. |

20 master-level service design students. 15 social workers involved in the weekly co-design workshops. 11 partners representing children, young people, parents, foster parents, bureaucrats, and researchers. Approximately 50 participants in exhibition and connected discussions. |

11 prototypes made through the co-design sessions. Memos and reflection notes written by students in various stages of the exploration. Reflection notes written by participating social workers after the exploration. Presentation and zines describing the process and aim for all prototypes. |

Exploration 1 was collaboratively led by the first author and social workers in the child welfare organization. It centered around a dialogue lab and comprised more than 140 hours of collaborative inquiry (Heron & Reason, 2006). The inquiry aimed to create collective dialogues that enhanced social workers’ ability to shape their relations through reflexivity. This was explored by prototyping variations in dialogue content, structure, and conditions that enabled participants to address the meanings and values that underpinned taken-for-granted scripts among child welfare workers. The entire child welfare organization participated in various prototyping activities. In addition to the first author’s experiences and participant observation from the inquiry, documented materials from the exploration included reflection notes and transcribed focus group discussions from the lab members, feedback and reflection notes from other participating social workers, as well as sketches, process photos, and other materials produced through the design process.

Exploration 2, The Relational Drama in Child Welfare, was led by the first author and involved the collaboration of 100 system actors, 15 master-level design students, and 13 graduate students in acting and script writing. This exploration aimed to spark conversations among system actors about the scripts used within child welfare and their underlying meanings. We focused on the emotional experiences system actors encountered in their relations within the child welfare system. Various experiments were conducted over four months, culminating in an interactive theater event with approximately 800 participants. Documented materials from this exploration included reflection notes written by participating design students and system actors, scripts, props, a complete recording of the theater event, and transcriptions of conversations among social workers after the event. These materials were complemented by participant observations and reflections from the first and second authors, who were involved throughout the exploration.

Exploration 3, Designing for Dignified Child Welfare, was led by the first and second authors and included a series of co-design prototyping experiments conducted in collaboration with 15 social workers and 20 master’s degree design students. This exploration aimed to design feedback loops that enhanced dignity in child welfare relations. Over eight weeks, various prototypes were developed and tested based on the situated relations of the social workers involved. In three extended co-design workshops, other system actors were invited into the design process. The exploration culminated in an exhibition, where approximately 50 system actors participated in discussions around the prototypes. Empirical materials from this exploration include participant observations from the first and second authors, prototypes, presentation slides, booklets describing the prototypes, and memos and reflection notes from participating students and social workers.

Consolidating Analysis

To consolidate our findings after the conclusion of the explorations, we conducted an abductive analysis, which involves an iterative process of comparing empirical material with existing theoretical frameworks to generate or refine theory (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012, p. 179). In the analysis, we sought to develop actionable design principles for enabling actors to shape their relations themselves within public service systems. Design principles are knowledge derived from situated experience and empirical material—in this case, our explorations within Norwegian child welfare—that provide actionable guidance for design processes in broader problem areas (Sein et al., 2011; Fu et al., 2016).

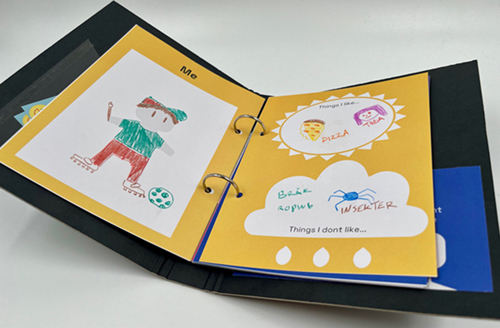

The co-authors conducted the consolidating analysis in thirteen sessions, each lasting 60 to 120 minutes, to recursively propose, refine, and delineate the design principles. The empirical material from the experiments served as the foundation for the analysis. Materials documented in Norwegian were translated to English with Autotekst, an AI software developed by the University of Oslo, powered by Whisper from OpenAI. The first author, who is bilingual in Norwegian and English, reviewed the translations. We focused on one experiment at a time, unpacking how each potentially enabled relational adaptation among system actors. This involved revisiting artifacts from the experiments, documented reflections from system actors, as well as observations and experiences from the first and second authors. The approach allowed us to propose initial design principles, which we subsequently refined. For instance, a recurring theme in the experiments was how children and young people often had limited agency in shaping their relations. One prototype addressed this issue by creating a book where children could express their feelings and concerns through drawing, coloring, and writing. In meetings with social workers, children could then use this book to express more clearly what was important in their lives. Inferring from this example, we developed an initial design principle that suggested that design could support relational adaptation by creating tools that intentionally give certain actors greater agency in defining the terms of their interactions.

We applied relational theory from social constructionism and sociology to interpret the mechanisms through which these design principles could enable relational adaptation among actors in public service systems. In the abovementioned example, the initial formulation was refined based on the understanding that, from a relational perspective, the scripts guiding actors’ relations are always written collectively. This prompted us to further develop the formulation of the principle from a relational perspective, focusing on design’s potential to encourage entangled actors to co-author these scripts as a principle for relational adaptation. Using abductive inference, we integrated these inputs non-linearly and refined the design principles by comparing empirical material and relational theory in several rounds of iterative revision. This process resulted in five distinct design principles, which structure the findings of this research.

The consolidating analysis was collaborative (Cornish et al., 2013), leveraging our distinct perspectives shaped by our varied roles and professional backgrounds. The first and second authors led the design experiments and analysis, with periodic sensemaking check-ins with the third author. The first author brought eight years of professional experience in Norwegian child welfare, including within the main collaborating organization. The second author contributed extensive service design experience from more than 15 years of practice and research within public service systems, primarily in North America and Scandinavia. The third author contributed over 20 years of experience in service design research, particularly within healthcare in the UK and Italy. These differing backgrounds and roles enabled us to maintain both insider and outsider perspectives on the empirical materials and the research context.

Findings

Our abductive analysis reveals five design principles grounded in relational theory and demonstrated through practical experiments. Combined, these principles offer an actionable approach to enable relational adaptation among actors in public service systems. Here, we define relational adaptation as the joint, ongoing process through which actors within service systems shape their relations to be meaningful. The capability for relational adaptation resides within the entangled relations actors are embedded in, and it is enabled or constrained by their manifold indirect and interdependent relations to others within the service system.

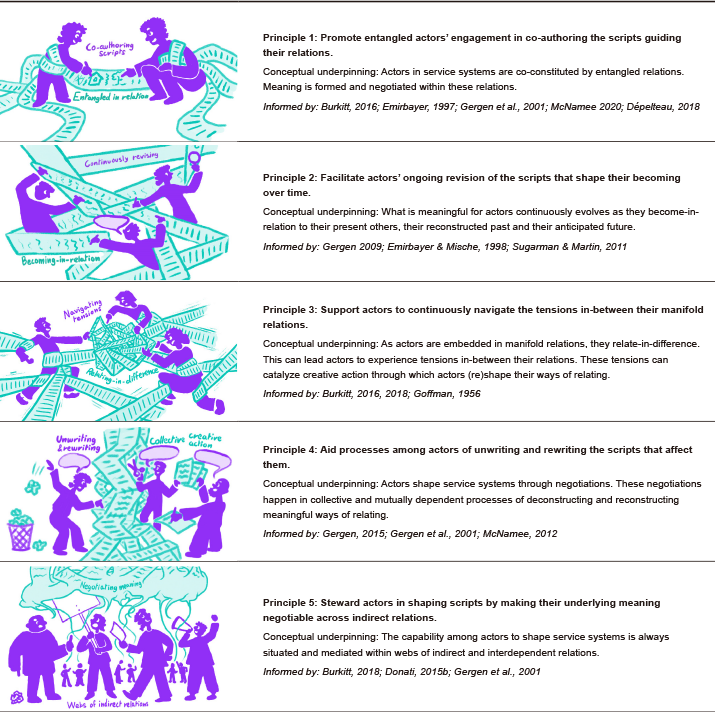

The design principles, summarized in Table 2 with their conceptual underpinnings from relational theory, suggest that this capability can be cultivated by design through (1) Promoting the co-authoring of scripts, (2) Facilitating ongoing script revision, (3) Supporting the navigation of relational tensions, (4) Aiding the unwriting and rewriting of scripts, and (5) Stewarding the negotiation of meaning across relations. While the design principles were developed from a wide range of empirical materials, we demonstrate them here through specific examples from our explorations.

Table 2. Design principles with conceptual underpinnings informed by relational theory. (Illustrations: Magnus Winther)

Promoting Co-Authorship of Scripts

“In such a system, when making changes that may benefit some but harm others, whose interests should take priority? Can we balance different needs and interests?”

These rhetorical questions from a student’s reflection note capture a realization that emerged throughout our research: the more we engaged with the child welfare system, the clearer it became that actors within such a system are deeply entangled. For example, how a young person relates to their foster parents is significantly influenced by how their biological family reacts to them living in a new family. A social worker’s relation with a family is influenced by the support they receive from their colleagues and leaders. A leader’s relation with their staff is influenced by the resources provided by policymakers. The relations a mother involved with child welfare has with her friends are influenced by how child welfare is portrayed by the media. These dynamics highlight the relational interdependencies within public service systems, whereby changes in one relation are always affecting and affected by other relations. As the student’s reflection note indicates, the realization of actors’ interdependence underscored the potential harm that could be inflicted if we, as designers, were to one-sidedly create or alter ways of relating among system actors without accounting for these interdependencies. There is a risk of producing unintended consequences by imposing changes in these relations that do not account for the effect on other actors. To avoid this, we rather sought to promote the capability of situated actors to collectively shape and navigate changes in their own relations together with entangled actors. This is reflected in the first design principle for how design can enable relational adaptation in public service systems:

Principle 1: Promote entangled actors’ engagement in co-authoring the scripts guiding their relations.

From a relational perspective, individuals are co-constituted by their relations (Gergen, 2009), highlighting how actors’ roles and actions in service systems always emerge in relation to interdependent others (Dépelteau, 2018; Emirbayer, 1997; Gergen, 2015). These roles and actions are shaped by the shared scripts within the system. Scripts give actors roles—such as that of a professional or a client—which set expectations for how they should interact. These scripts are grounded in the shared meanings within the system (Gergen, 2015). What it means to act professionally is negotiated through common understandings of language and cultural practices (Gergen, 2009). Thus, the scripts that guide actors’ relations are written collectively (McNamee, 2020). However, when certain actors are excluded from bringing forward their perspectives in this collective authorship, the scripts may not reflect what is considered meaningful and appropriate to them. Consequently, involving entangled actors as co-authors of the scripts guiding their relations increases the likelihood that the scripts will be meaningful and appropriate to those affected.

An example of designing to promote actors’ engagement in co-authoring scripts was explored through the “My book” experiment. We learned that children and young people’s participation in co-writing their scripts was both a significant challenge and of particular importance within the child welfare system. While both the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1989) and Norwegian law (Lov om Barnevern, 2023) give children and young people the right to participate in matters that affect them, system actors highlighted that this is not always achieved in real-life settings. Social workers expressed that children often struggled to express their needs, frequently responding with “I don’t know” to social worker’s questions about their opinions, needs, and desires. The ‘My book’ prototype, depicted in Figure 2, was co-designed with social workers and young people with lived experience. They aimed to explore how design could facilitate children’s active engagement in influencing their relations with social workers. The prototype consisted of a binder where children could express their feelings, hopes and concerns through drawing, coloring, and writing in developmentally appropriate ways. By bringing this book to meetings with social workers, the child’s expressions enabled social workers to better engage with the child’s lifeworld. Participants noted that this approach gave the child a greater influence in how they were met by their social worker. The child’s lifeworld became the starting point of the conversation, rather than the social workers’ often difficult-to-answer questions.

Figure 2. The “My book” prototype. (Design: Per Roppestad Christensen, Matilde Petlund & Sarah Erin Braathen)

Facilitating Ongoing Script Revision

“I believe this process has made me braver. That’s the small and huge change … It’s small because the only difference is that I now dare to ask slightly different questions than I did before. But it’s also huge because that openness has profoundly impacted how I meet others.”

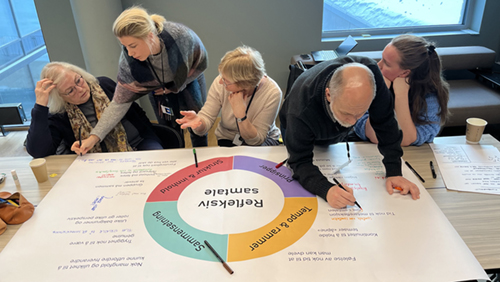

This quote, shared by a social worker, highlights an insight that emerged among the participants in the dialogue lab. The goal of this exploration was to create conditions for dialogue among social workers that enhanced their capability to shape their relations within the service system. Initially, the lab sought to design concrete measures and methods for achieving this goal. However, through the experimentation process, participants found that their ability to shape relations emerged from the joint, ongoing conversations they had with one another during the inquiry. Participants noted that the lab created a space where they could reflexively engage with core dilemmas in their practice and that this engagement challenged their taken-for-granted assumptions. In discussions like the one depicted in Figure 3, one participant’s perspective often disrupted others’ views, and vice versa. Their engagement not only changed their perspectives within the lab but also sparked new ways of relating with colleagues, clients, and others outside of it. These dynamics highlight the second design principle for how design can enable relational adaptation in public service systems:

Principle 2: Facilitate actors’ ongoing revision of the scripts that shape their becoming over time.

Relational perspectives emphasize that actors’ being in a service system is not static but continually evolves as actors become-in-relation with entangled others (Gergen, 2009). As shared meanings within the system are constantly negotiated among actors, their roles and interactions change accordingly (Burkitt, 2018). However, as actors become-in-relation with others over time, they do so not only in relation to others but also in relation to their reconstructed past and anticipated future (Burkitt, 2018). This situates actors in various unique “temporal-relational contexts” (Emirbayer & Mische, 1998, p. 969), where distinct perceptions of meaning are formed and constantly evolve. What actors find meaningful is, thus, always in flux as they become-in-relation (Sugarman & Martin, 2011). Their capability to shape the scripts guiding their interactions also emerges within these unique temporal-relational contexts in relation to others in the present, their personal biographies, and their future aspirations. Therefore, the capability to shape relations requires a continuous revision of scripts, based on actors’ evolving conceptions of meaning as they become together over time.

Among the participants in the dialogue lab, active engagement in script revision emerged through ongoing dialogues that included multiple perspectives. These dialogues helped participants alter their ways of relating outside of the lab. To embed this capability across the child welfare organization, these dialogues were mirrored through designing and establishing an ongoing dialogue forum structure. In total, eight ongoing forums were established. In each of these, 15 social workers met every second week for one-and-a-half hours, engaging in open, collective dialogues about the challenges and meanings in the scripts they performed in their day-to-day practice.

Figure 3. Participants in the dialogue lab engage in joint dialogue.

Supporting the Navigation of Tensions

Throughout our research project, young people, parents, foster parents, and social workers reported a variety of challenging experiences within the child welfare system. For example, young people struggled with balancing loyalty to their biological families while integrating into foster families; parents found it challenging to be vulnerable and ask for help while their network urged them to “fight” for their children; and social workers found it challenging to adapt their approach to each family’s needs while adhering to organizational protocols and guidelines. The diverging expectations within and between relations were experienced as tensions among the actors.

These tensions were explored through “The Stretch” prototype, depicted in Figure 4. The prototype used elastic rubber bands stretched between various expectations within the social worker’s role. The more contradictory the expectations, the greater the tension in the band. Materializing the experienced tensions allowed social workers to acknowledge and explore the underlying causes of these feelings and collectively navigate them.

Figure 4. “The Stretch” prototype. (Design: Maija Hauger & Hege Santi)

“The Stretch” exemplifies the third design principle for how design can enable relational adaptation among actors in public service systems:

Principle 3: Support actors to continuously navigate the tensions in-between their manifold relations.

From a relational perspective, service systems function as webs of manifold relations (Burkitt, 2016). Actors occupy different positions in these relational webs (Goffman, 1956). As they relate-in-difference, their positionality brings differing perceptions of meaningful ways of relating, thereby causing tensions between actors (Burkitt, 2018). Additionally, actors can experience tensions when trying to simultaneously perform the various scripts expected in the multiple relations they are embedded in (Burkitt, 2018). For instance, young people told us they found it difficult to respond when foster parents expressed love as if they were their own children, while their biological parents claimed that they would always be their actual parents, all in a culture where children typically have only one set of primary caregivers. However, these tensions can serve as a driver of script revision within the system. The experience of tensions in-between actors’ relations can prompt them to negotiate or resolve them. As these processes evolve, this continuous navigation among actors can be seen as an ongoing mechanism for emergent redesign within the service system.

Design can support this navigation by raising awareness among actors of the multiple tensions that exist in-between relations in the service system. In one experiment, we collaborated with over 100 system actors to create a two-hour play. In the play, theater actors portrayed how various relations within the child welfare system were experienced through fictional characters. An image collage from the play is depicted in Figure 5. The goal of this experiment was to expose the tensions actors experienced in-between their roles. To make the enactments authentic, we worked actively with what is often referred to in theater as subtext. Known from Stanislavski’s theater practice (Knebel, 2021; Moore, 1984), subtext represents the unspoken tensions and conflicts underlying characters’ spoken dialogue. Through embodied, often nonverbal enactments of the script, spectators can grasp the complexities and tensions in the relations among individual characters (Knebel, 2021). As one student reflected, focusing on these tensions allowed us to show:

… how a parent on the one hand can wish to take care of their child and on the other can need time and help to get back on their feet … [or how] a case worker has a large workload, needs to be a friend and guardian to children, and has to navigate their own emotions in a case, all this within a 9 to 5 work schedule.

After seeing the play, some participating social workers noted a shift in their conversations with their colleagues. They expressed a desire for more collective discussions on how to navigate the dilemmas and tensions they experienced in-between their relations in the system. We interpreted this as an inspiration to navigate these tensions more proactively, as participants sought ways of relating that could better accommodate the challenges they faced.

Figure 5. Images of related characters from the interactive theater event. (Photos: Kristiania/Jonatan Quintero)

Aiding Unwriting and Rewriting

For children, young people, and their families to be supported within child welfare, actors rely on scripts to coordinate their interactions. However, our experiments taught us that predefined scripts often did not fit actors’ situations, circumstances, or backgrounds. For instance, the scripts for therapy typically suggest setting goals based on areas in a young person’s life that need improvement, with a therapist providing expertise to help achieve these goals. However, a young person may not have clear answers about what needs to be improved, and their therapist may not know how to help them. In such instances, the scripts guiding these interactions need to be revised.

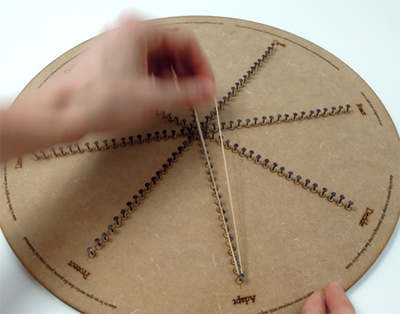

Our experiments explored how such revisions could be supported among actors. One example is the “Materials for Conversation” prototype, designed to help actors collectively revise their scripts. As depicted in Figure 6, the prototype consisted of three simple material components: First, a small whiteboard served as a blank canvas for the relational script, inviting families and the therapist to write the script together. Second, erasable markers allowed them to literally unwrite and rewrite what was meaningful in their relation. In Figure 6, these meanings include compassion, attentiveness, care, and honesty (depicted in Norwegian). Lastly, movable strings enabled actors to dynamically change the importance of these meanings throughout the therapy process. The prototype was co-designed with a family therapist, who explored ways to disrupt pre-scripted ways of engaging with clients. It instead invited them to collectively rewrite how she best could support them.

Figure 6. The “Materials for Conversation” prototype. (Design: Benjamin Romm & Caroline Alvestad)

The “Materials for Conversation” prototype illustrates the fourth design principle for how design can enable relational adaptation in public service systems:

Principle 4: Aiding processes among actors of unwriting and rewriting the scripts that affect them.

The benefit of scripts is that they provide shared expectations that support actors’ coordination to co-create certain forms of value. However, these scripts are not static; they are continuously revised based on what is considered to be of meaningful value within the system. This revision occurs through mutually dependent unwriting and rewriting (Gergen, 2015). In these processes, actors creatively unwrite current relational scripts that they do not find meaningful and rewrite them into more meaningful ones. However, since actors are always entangled and perform scripts in relation to others, individual actors cannot revise them alone (Gergen et al., 2001; McNamee, 2012). Effective revision thus requires joint unwriting and rewriting (McNamee, 2020). For example, a therapist unsure of how to help a family depends on the family’s willingness to revise the pre-scripted role of the therapist as an expert. The capability among actors to shape relations into meaningful forms thus hinges on their collective engagement in processes of unwriting and rewriting the scripts that influence them to become meaningful.

To explore how collective unwriting and rewriting of relational scripts could be aided through design, we drew on forum theater practices (Boal, 2008; van Amstel, 2023). In a series of workshops, theater actors performed scripted scenes while participating system actors suggested, co-directed, and discussed revisions. By exploring how everyday situations in the child welfare system could unfold with altered scripts, participants engaged in a form of relational prototyping. Some explored scripts mirrored participants’ real-life experiences, while others were more speculative. For instance, Figure 7 depicts an exploration where foster parents directed a scene of a young person shouting at them, claiming they only cared because they were paid to do so. By testing different responses, the foster parents explored how their role as “paid” caregivers could be redefined. After the workshops, participants reflected that engaging with scripts in this iterative way aided more generative negotiations of them.

Figure 7. Foster parents co-directing theater actors in a workshop setting.

Stewarding Negotiations of Meaning

Our experiments showed that system actors’ capability to shape their relations was situated in a broader network of indirect relations. This was illustrated by a barrier faced in an experiment to create more relationally attuned evaluation practices within child welfare. In co-design workshops, design students collaborated with social workers whose job was to gather feedback from families who had participated in a family therapy program. The feedback was obtained using a predefined form with questions like “Have you experienced the program as valuable?” that required yes or no answers. These dichotomous responses provided little insight into how the therapists could adapt their approach based on the families’ specific situations and experiences. As alternative approaches were explored, it became clear that the social workers had limited ability to shape their practice because the program and its evaluation were licensed as an evidence-based method by an international corporation. This corporation relied on standardized protocols to market the program as evidence-based, and altered evaluation procedures could risk the municipality losing access to the program. The social workers’ lack of agency in changing this script signifies the final principle for how design can enable relational adaptation in public service systems:

Principle 5: Steward actors in shaping scripts by making their underlying meaning negotiable across indirect relations.

Service systems involve both direct and indirect interdependent relations (Burkitt, 2018). For example, the direct relation between a social worker and a family is mediated by indirect, interdependent actors like politicians negotiating laws that shape the relation’s premises. The scripts that actors perform are embedded within broader value systems, shaped by what actors external to the relation—such as researchers, politicians, corporations, managers, the media, and the general public—consider meaningful (Donati, 2015b; Gergen et al., 2001). As the scripts are written based on these meanings, the capability among actors to shape them depends on the unseen power dynamics and values in their indirect relational network (Burkitt, 2018). To enable actors to shape their relations, the underlying meaning of the scripts for these relations needs to be negotiated across the indirect relations they are embedded within.

We suggest that design can steward such negotiations by making the meanings underlying service scripts explicit while engaging actors with diverse relational positions. In a series of experiments, we aimed to surface meanings attributed to concepts like expertise, family, children’s rights, responsibility, and care within child welfare through critical design and interactive theater. In these experiments, young people, parents, foster parents, social workers, bureaucrats, and politicians engaged in various interactive experiments. Figure 8 depicts one of these experiments, where participants visited a fictional political fair and interacted both with each other and with politicians from various parties who advocated different views on what constitutes a good family. At the fair, participants were exposed to a political debate, asked to vote for their favorite party, and discussed the election results together. Other experiments included an auction to determine the value of different forms of care and a hypothetical community meeting set in 2050, after the dissolution of the child welfare system, prompting participants to discuss who should bear the responsibility for children’s well-being. Surfacing these meanings in speculative and interactive ways amid broader collectives of actors, prompted actors to discuss how these meanings underpinned their own and others’ everyday practices and experiences within the system.

Figure 8. Participants negotiate meaning in a fictive political fair.

Enabling Relational Adaptation in Public Service Systems

Figure 9 summarizes the five design principles for enabling relational adaptation in public service systems. Our findings suggest that relational adaptation can be enabled by addressing these interdependent processes. The five proposed design principles—promoting the co-authoring of scripts, facilitating continuous script revision, supporting the navigation of tensions, aiding unwriting and rewriting, and stewarding the negotiation of meaning—combine to form an actionable design approach. This approach focuses on facilitating actors’ ongoing re-scripting of their relations in public service systems, rather than pre-scripting and standardizing them. Through joint re-scripting, affected actors are enabled to collectively shape public service systems in continuous bottom-up transformation based on what they find meaningful.

Figure 9. Ongoing transformation in public service systems through relational adaptation among actors. (Illustration: Magnus Winther)

Discussion

This research outlines design principles for enabling relational adaptation in public service systems. The principles advance service design practice within the public sector and contribute to the academic discourses of service design and public management. First, the principles help to reconceptualize service scripts from a relational perspective, enabling actors to intentionally adapt the service systems they inhabit through continuous re-scripting. Second, the design principles offer a novel approach to stewarding service system transformation by demonstrating how relational adaptation can become an ongoing bottom-up process, allowing for the purposeful evolution of these systems over time. Lastly, these principles advance a relational ontology for service design within public service systems and beyond that acknowledges the entangled constitution of actors in these systems. Below, we discuss each of these contributions, the implications for public service design practice and theory, and future research directions emerging from this exploratory work.

Reconceptualizing Service Scripts from a Relational Perspective

This research reconceptualizes the traditional understanding of service scripts as standardized, predefined roles and actions that employees perform during service interactions (Harris et al., 2003; Victorino et al., 2013). Drawing on relational theories from sociology (e.g., Burkitt, 2016) and social constructionism (e.g., McNamee, 2012), we propose service scripts not as fixed instructions for actors to follow but rather as situated, entangled, and processual structures continuously shaped by actors within service systems. While scripts remain crucial for actors’ coordination to co-create value within service systems, a relational perspective emphasizes that these scripts emerge from relational processes and shared meanings among actors within service systems. This perspective implies that actors can engage in ongoing re-scripting based on what they consider meaningful ways of relating, rather than following pre-scripted interactions imposed by others external to the situation. This reconceptualization shifts the assumptions regarding actorship within service scripts, from seeing actors as separate individuals performing specific roles to seeing actors as entangled, interdependent and co-constituted by relations.

By recognizing that actors co-constitute each other through their relations, we bring forward an understanding of re-scripting as a collaborative, ongoing process shaped by the evolving and manifold relations among actors. To support more dignified service experiences among diverse actors (Kim, 2021), this research suggests that service design can enable the continuous renegotiation of scripts among actors grounded in their situated needs and contexts. Furthermore, this view highlights that the capability of actors to intentionally adapt the service systems they inhabit is relational. The focus on how these capabilities are entangled and reside in the relations among actors deepens the current discussions on relational reflexivity as a means of fostering intentional transformation in service systems (Vink & Koskela-Huotari, 2022). This understanding of re-scripting relations also provides a humble antidote to the locked-in effect perpetuated by standardized service scripts, typical in outdated, legacy service systems in the public sector (Karpen et al., 2022).

This research raises further questions about re-scripting relations within and beyond public service systems. First, additional research is needed to understand and mitigate the risks of re-scripting, such as causing confusion leading to paralysis in urgent situations or creating role ambiguity, which may lead actors to abandon ethical protocols. To what extent should scripts become adaptable in various public service settings, or where might standardized scripts still have a role to play in mitigating such risks? Second, power is highlighted as a key issue in relationally focused design approaches (Light & Akama, 2014; Udoewa & Gress, 2023). The practice of re-scripting relations would benefit from research diving deeper into the power dynamics of re-scripting processes, particularly within hierarchical and highly regulated settings within public service systems. In addition, further work is needed to understand how best to include actors that might be hindered from participating in re-scripting, such as severely ill individuals or marginalized communities. Moreover, questions remain regarding how best to account for the indirect effects that situated processes of re-scripting might have on more peripheral actors, such as family members of service users.

Delineating a Novel Approach for Stewarding Service System Transformation

There are growing ambitions within public management discourse to transform relations among actors in public service systems, from being pre-scripted and transactional to becoming more adaptable and collaborative (Torfing & Ansell, 2021; Von Heimburg & Ness, 2021). The design principles from this research offer guidance on how design practitioners and service managers can steward transformative processes that are both intentional and emergent. While intentional adaptation aims at desired outcomes, such as ensuring dignity for all actors, these outcomes are achieved through actors iteratively refining their relations in a process of ongoing self-organization within the service system. Although design scholars have acknowledged processes of value co-creation (Wetter-Edman et al., 2014), design-in-use (Henderson & Kyng, 1995; Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011), design after design (Ehn, 2008), and ongoing designing (Akama & Prendiville, 2013; Sangiorgi & Prendiville, 2017; Vink et al., 2021), whereby actors continue to shape designs after the conventional design process, there is a scarcity of practical guidance on how to steward actors’ ongoing and collective design processes in service systems. The design principles outlined here aim to help designers and managers move from merely acknowledging these ongoing processes to actively mobilizing and amplifying them, supporting actors to purposefully and collectively shape service systems.

Enabling relational adaptation through design is not a top-down systemic shift from one system state to another but rather a bottom-up process in which small-scale relational shifts among actors contribute to the service system’s purposeful evolution over time. This differs from other discussions of transformation and systems changes focusing on realizing a singular desired future state within the collective (e.g., Curry & Hodgson, 2008). Instead, this process acknowledges and nurtures the relational capabilities of actors to continuously shape their service systems from within. In addition, the design principles for relational adaptation build a bridge between typically conceptual, theory-driven research on designing for service systems transformation and more practice-based, situated research on improving user experiences (Hay & Vink, 2023). This research, therefore, offers a situated, systemic approach to designing public service systems from within. The theoretical foundations of the principles contribute to building a more relational vocabulary for service design, extending the emerging perspective on service systems as evolving entanglements (Akama & Yee, 2023). This can inspire design practitioners and service managers to realize co-creative ambitions by activating actors in an interdependent, relational process of public service design.

While this research explored design approaches to stewarding system transformation through relational adaptation, questions remain about how such approaches can be effectively embedded and sustained within public service systems over time. To understand this better, we call for longitudinal research that can help to delineate the barriers and facilitators for maintaining appropriate, ongoing transformation in public service systems. This research could examine the organizational and systemic structures that enable or constrain bottom-up transformation through relational adaptation across various public service systems. In particular, there is a need to understand how managerial and evaluation structures can balance consistency and adaptability over time. Second, future research should critically explore how situated, actor-driven adaptation within public service systems can be balanced with broader public values. For example, do some adaptations conflict with collective public values, and if so, what approaches can help manage these tensions in just ways? These questions are crucial to ensure that emergent adaptation does not jeopardize essential roles of public systems, such as ensuring equity for minorities or considering the rights of future generations.

Advancing a Relational Ontology in Public Service Design

The strong influence of a market-based logic on public service design (Akama et al., 2023; Kimbell & Bailey, 2017; Osborne et al., 2013; Torfing et al., 2019) has advanced a transactional approach to service provision in the public sector, emphasizing individualism and efficiency. This logic is reflected and reinforced by popular service design tools, such as the service blueprint, which centers on the individual service user’s journey and delineates distinct roles and activities for service providers (Vink & Koskela-Huotari, 2022). As Escobar and colleagues (2024, p. 261) note, “most design has been performed nonrelationally. The very concepts of designer, user, object, project, and interface reveal the nonrelational structure of design.” However, there is an emerging discourse that aims to bring in more relational approaches to public service design under banners such as relational welfare (Cottam, 2011; Von Heimburg & Ness, 2021), relational service design (Cipolla & Manzini, 2009; Nielsen & Bjerck, 2022) and relational practices (Duan, 2023). This research strengthens these efforts by drawing directly on relational theory to recognize the entangled and interdependent nature of actors’ existence, supporting the necessary ontological shift for realizing relational approaches to public service design.

Moreover, this research demonstrates how adopting a relational ontology shifts the very nature of service design. While service design discourse has highlighted the importance of relations (see, e.g., Aguirre Ulloa & Paulsen, 2017), it has typically done so in ways that reinforce the separateness of actors, with systems portrayed as something existing externally to them, such as through the use of actor maps (Curedale, 2013). This research demonstrates how a relational ontology can aid designers and managers to work proactively with the ways we are already co-inventing ourselves and the world around us (Escobar et al., 2024) as we do things together with others (Duan, 2023). In increasingly fragmented and diverse societies, this research suggests that design approaches that attend to the interdependence of all that exists can offer alternative strategies for designing public service systems. These strategies may be better suited to the multiple interests in the public sector and the entangled global crises these systems are embedded in.

While this research advances a relational ontology in service design, it draws primarily on relational perspectives from social theories focusing on human relations. These perspectives do not adequately account for more-than-human actors—such as technology and other than human living beings—and their roles in shaping actors and service systems (see, e.g., Tsing, 2015). As a relational ontology for service design is advanced, there is a need to explore how more-than-human actors influence relations in service systems and what implications this has for service design. Additionally, if service design research is to adopt a relational ontology, it would benefit from learning in dialogue with relational ways of knowing and being beyond those originating in Euro-Western scholarship, such as Indigenous knowledge systems (Todd, 2016; Yunkaporta, 2019). Furthermore, there are inspiring models of conducting and sharing research that account for relationality, including by supporting the struggle to community self-determination (Tuhiwai Smith, 1999) and working with the co-existence of multiple knowledges (Goodchild, 2021). This means that not only are service designers’ practices transformed by recognizing relationality, but so too are the practices of scholars and the ways we co-create knowledge together.

Conclusion

Responding to the growing calls for actors to actively shape public service systems, our aim in this research has been to develop an actionable service design approach that enables actors within public service systems to adapt their relations themselves, instead of having these relations pre-scripted by others. We propose enabling relational adaptation––understood as actors’ joint and ongoing shaping of their relations by themselves––as a grounded and situated approach for continuous service system redesign. Informed by a relational ontology, this approach deepens efforts to move away from market-based assumptions in public service design and the object-oriented ontologies prominent in design more broadly. The proposed design principles demonstrate how design can enable ongoing re-scripting among actors, rather than pre-scripting interactions for them to follow. In doing so, the principles support transforming public service systems from static, legacy systems into adaptive systems that can respond to the evolving needs and diverse contexts of the actors involved. This research, thus, outlines an actionable and intentional role for design and designers to support ongoing, emergent transformation in public service, where these systems are continuously designed and adapted by the actors involved, based on what is relevant and meaningful to them.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly funded by The National Research Council of Norway and Bærum Municipality. We would like to thank all the contributing partners for their collaboration and joint learning throughout the research project. Special thanks to the students, researchers, and staff at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design and Kristiania University College for their enthusiasm and participation in the experiments. We are also grateful to our collaborating partners within the Norwegian child welfare system, including Bærum Municipality, Landsforeningen for barnevernsbarn, Foreldreinvolverings-prosjektet, Fosterhjemsforeningen, ADHD Norge, the County Governor of Oslo and Viken, the Norwegian Ombudsperson for Children, KS, and others. Lastly, we want to thank Dagfinn Mørkrid Thøgersen for giving valuable feedback in the development of this article.

References

- Aguirre Ulloa, M. (2020). Transforming public organizations into co-designing cultures [Doctoral dissertation, Oslo School of Architecture and Design]. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2654789

- Aguirre Ulloa, M., & Paulsen, A. (2017). Co-designing with relationships in mind. FormAkademisk, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.1608

- Akama, Y., Light, A., & Agid, S. (2023). Amplifying the politics in service design. Strategic Design Research Journal, 16(1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.4013/sdrj.2023.161.04

- Akama, Y., & Prendiville, A. (2013). Embodying, enacting and entangling design: A phenomenological view to co-designing services. Swedish Design Research Journal, 13(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.3384/svid.2000-964X.13129

- Akama, Y., & Yee, J. (2023). Introduction. In Y. Akama & J. Yee (Eds.), Entanglements of designing social innovation in the Asia-Pacific (1st ed., pp. 1–20). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003244684-1

- Alessi, E. J., & Kahn, S. (2022). Toward a trauma-informed qualitative research approach: Guidelines for ensuring the safety and promoting the resilience of research participants. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 20(1), 121–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2022.2107967

- Anderson, S., Nasr, L., & Rayburn, S. W. (2018). Transformative service research and service design: Synergistic effects in healthcare. The Service Industries Journal, 38(1–2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2017.1404579

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2007). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Bang, A. L., & Eriksen, M. A. (2014). Experiments all the way in programmatic design research. Artifact, 3(2), Article 4. https://intellectdiscover.com/content/journals/10.14434/artifact.v3i2.3976/art.3.2.4.1_1

- Bekaert, S., Paavilainen, E., Schecke, H., Baldacchino, A., Jouet, E., Zabłocka-Żytka, L., Bachi, B., Bartoli, F., Carrà, G., Cioni, R. M., Crocamo, C., & Appleton, J. V. (2021). Family members’ perspectives of child protection services, a metasynthesis of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review, 128, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106094

- Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Mohr, L. A. (1994). Critical service encounters: The employee’s viewpoint. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800408

- Boal, A. (2008). Theatre of the oppressed. Pluto Press.

- Brandt, E., & Binder, T. (2007). Experimental design research: Genealogy, intervention, argument. Paper presented at International Association of Societies of Design Research 2007: Emerging trends in design, Hong Kong, China. URL: https://www.sd.polyu.edu.hk/iasdr/proceeding/papers/Experimental%20design%20research_%20genealogy%20-%20intervention%20-%20argument.pdf.

- Brandt, E., Redström, J., Eriksen, M. A., & Binder, T. (2011). XLAB. The Danish Design School Press.

- Brodkin, E. Z. (2006). Bureaucracy redux: Management reformism and the welfare state. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 17(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muj019

- Burkitt, I. (2016). Relational agency: Relational sociology, agency and interaction. European Journal of Social Theory, 19(3), 322–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431015591426

- Burkitt, I. (2018). Relational agency. In F. Dépelteau (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of relational sociology (pp. 523–538). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66005-9_26

- Callahan, R. F., & Gilbert, G. R. (2005). End-user satisfaction and design features of public agencies. The American Review of Public Administration, 35(1), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074004272620

- Cipolla, C., & Manzini, E. (2009). Relational services. Knowledge, Technology & Policy, 22, 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12130-009-9066-z

- Cornish, F., Gillespie, A., Tania, Z., & Flick, U. (2013). Collaborative analysis of qualitative data. In U. Flick (Ed.) The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446282243

- Cottam, H. (2011). Relational welfare. Soundings, 48(11), 134–144. https://doi.org/10.3898/136266211797146855

- Cottam, H. (2019). Radical help: How we can remake the relationships between us and revolutionise the welfare state. Virago.

- Curedale, R. (2013). Service design: 250 essential methods (1st ed.). Design Community College.

- Curry, A., & Hodgson, A. (2008). Seeing in multiple horizons: Connecting futures to strategy. Journal of Futures Studies, 13(1), 1–20.

- Dépelteau, F. (2018). Relational thinking in sociology: Relevance, concurrence and dissonance. In F. Dépelteau (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of relational sociology (pp. 3–33). Springer.

- Diefenbach, T. (2009). New public management in public sector organizations: The dark sides of managerialistic “enlightenment.” Public Administration, 87(4), 892–909. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01766.x

- Dietkus, R. (2022). The call for trauma-informed design research and practice. Design Management Review, 33(2), 26–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/drev.12295

- Donati, P. (2015a). Beyond the traditional welfare state: “Relational inclusion” and the new welfare society. In G. Bertin & S. Campostrini (Eds.), Equiwelfare and social innovation (pp. 13–50). Franco Agneli. http://rgdoi.net/10.13140/RG.2.1.2737.7687