Emotions by Design: A Consumer Perspective

Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, USA

What is the relationship between attribute tradeoff decisions at the time of purchase and emotional content of the consumption experience? This article offers a comprehensive overview and an enhanced model of the possible forms of this relationship. It sets forth new insights into negative post-consumption emotions in an integrated manner with prior work on attribute tradeoffs and positive emotions. The primary insights this research provides are as follows: (1) a negative experience with the choice of a product with superior utilitarian and inferior hedonic benefits (e.g., a highly functional cell phone with poor attractiveness) over a product with superior hedonic and inferior utilitarian benefits evokes feelings of sadness, disappointment, and anger, (2) a negative experience with the choice of a product with superior hedonic and inferior utilitarian benefits (e.g., a highly attractive cell phone with poor functionality) over a product with superior utilitarian and inferior hedonic benefits evokes feelings of guilt and anxiety. Further, an enhanced model is presented that integrates the results for four new negative post-consumption emotions with the results from replication of prior work on positive emotions and consumer behavior. Finally, the research shows that positive and negative emotions impact customer loyalty. The article discusses the theoretical contribution and strategic insights the research provides for product designers and marketers.

Keywords – Hedonic Design, Utilitarian Design, Prevention Emotions, Promotion Emotions, Customer Loyalty.

Relevance to Design Practice – The paper clearly demonstrates that different design benefits lead to different types and intensities of both positive and negative consumption experiences. It makes a case for strategic approach to designing products that evoke desirable positive emotions and minimize negative emotions to enhance customer loyalty.

Citation: Chitturi, R. (2009). Emotions by design: A consumer perspective. International Journal of Design, 3(2), 7-17.

Received March 16, 2009; Accepted July 13, 2009; Published August 31, 2009

Copyright: © 2009 Chitturi. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

Corresponding Author: rac2@lehigh.edu.

“Chicago Diners weren’t really choosing between lousy food and good food but between good food in an

appealing environment and better food in an unappealing environment.”

— Virginia Postrel, Source: The Substance of Style.

Introduction

The ultimate measure of an effective design is the overall consumption experience it provides for the consumers by offering different types of benefits. An effective design generates desirable consumption experience and favorably influences subsequent consumer behavior (Chitturi, Raghunathan, & Mahajan, 2007; Desmet & Hekkert, 2007). This article adopts a two dimensional (hedonic and utilitarian) product benefits framework prevalent in marketing literature to explore the relationship between product design, consumption experience, negative emotions, and customer loyalty1. (Batra & Ahtola, 1990; Chitturi et al., 2007). The overall consumption experience is a function of a mix of different types of positive and negative emotions. Therefore, it is important for the designers to understand the relationship between the benefits they design into a product and the nature of the consumption experience as determined by its emotional content (Chitturi et al., 2008). After all, one of the main objectives of designers is to offer a unique experience to consumers to motivate them to indulge in positive word-of-mouth and improve the likelihood of repurchasing the product.

In a society that offers abundant choices among products, the ability of the consumer to make the right tradeoffs is critical to accomplishing the short-term objectives of satisfactory task performance. The ability to make the right tradeoffs is also critical to the long-term goals of fulfilling overall consumption experience. Here, satisfaction with the completed task depends on the tradeoff that maximizes the probability of fulfilling your task related objective. Further, fulfilling emotional experience depends on the overall emotional content of the consumption experience. However, it has been shown that the emotional content of the consumption experience is determined not only by the consumption of the product but also by the knowledge about the forgone product alternative (Chitturi et al., 2007, 2008; Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000). This is especially the case when consumption of the chosen product does not fulfill customers’ goals resulting in a set of negative post-consumption emotions—a key component of this paper.

In this paper, we demonstrate that consumption of hedonic and utilitarian design benefits evokes different types and intensities of negative and positive emotions. Specifically, we theorize and validate the presence of four new negative post-consumption emotions to enhance the model proposed by Chitturi et al. (2008 p. 49). This article builds on the idea that attributes that offer hedonic benefits and fail to fulfill expected consumption experience evoke a variety of negative emotions when compared with attributes that offer utilitarian benefits and have the same consumption experience. The prior work has focused primarily on post-consumption positive emotions whereas this paper explores negative post-consumption emotions in more detail.

This article progresses through a discussion of the conceptual framework with a review of the relevant literature to derive our main predictions about the negative emotions. The article then provides empirical tests of these predictions, and replicates prior work on positive emotions with the help of a second study.

An Enhanced Model of Tradeoffs,

Design Benefits and Consumption Emotions

This article improves the model proposed by Chitturi et al. (2008) by testing and integrating the four new negative emotions of guilt, anxiety, sadness, and disappointment with their model. The enhanced model offers a more complete picture of tradeoffs involving hedonic and utilitarian design benefits, and both negative and positive post-consumption emotions.

What are Utilitarian and Hedonic Benefits?

Here, the definitions of hedonic and utilitarian benefits used are consistent with prior work by Chitturi et al. (2007), Dhar and Wertenbroch (2000), and Okada (2005)2. In the literature, hedonic benefits are defined as those pertaining to aesthetic and experiential benefits that are often labeled as luxuries. Utilitarian benefits are defined as those pertaining to instrumental and functional benefits that are closer to necessities than luxuries (Batra & Ahtola, 1990; Chitturi et al. 2007; Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000; Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998). In the context of cell phones, for example, the phone’s battery life and network coverage are utilitarian benefits, whereas aesthetic appeal from its shape and color are hedonic benefits.

Understanding the tradeoffs involving these two benefit dimensions has been an area of active research in recent years (e.g., Chitturi et al. 2007, 2008; Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000; Kivetz & Simonson, 2002b; Okada, 2005; Voss, Spangenberg, & Grohmann 2003). Prior research has focused primarily on assessing the relative weight that consumers attach to these two dimensions in purchase decisions. For example, Chitturi et al. (2007) document that consumers attach greater importance to the hedonic (versus utilitarian) dimension, but only after a “necessary” level of functionality is satisfied. Similarly, Kivetz, and Simonson (2002a) document that consumers attach greater weight to the utilitarian (versus hedonic) dimension, unless they believe that they have “earned the right to indulge.” In contrast, this research focuses on the tradeoffs between these two design benefit dimensions within a chosen product, as well as between the chosen and the foregone product alternatives. Further, it studies the influence of tradeoff decisions on post-consumption negative and positive emotional and behavioral consequences.

What are Prevention and Promotion Goals?

The regulatory focus theory describes promotion goals to include aspirations of pleasurable consumption experience (Higgins, 1997, 2001). For example, “looking cool” or “being sophisticated” are promotion goals. Conversely, prevention goals are those that ought to be met such as “behaving in a safe and secure manner” and “being responsible” to avoid a painful consumption experience. What is the relative importance of hedonic and utilitarian design benefits for a consumer? Chitturi et al. (2007) shows there are two principles that determine the relative consumer preference involving tradeoffs between hedonic and utilitarian design benefits. They are, (1) the principle of precedence, and (2) the principle of hedonic dominance. The principle of precedence motivates consumers to assign greater importance to utilitarian benefits over hedonic benefits until a minimum threshold of functionality for fulfillment of prevention goals. However, beyond this minimum threshold of functionality, the principle of hedonic dominance motivates customers to assign greater weight to hedonic benefits over utilitarian benefits for fulfillment of promotion goals.

Tradeoffs, Consumption Experience, and Consumer Behavior

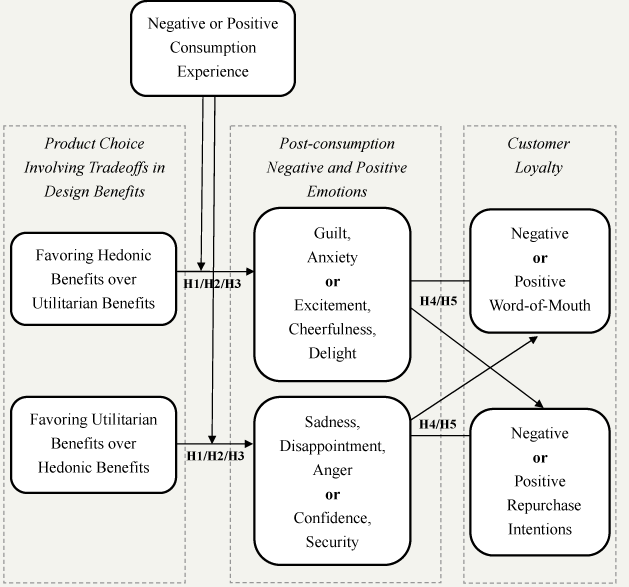

This paper adapts the conceptual framework developed by Chitturi et al. (2008) to include four new negative emotions of guilt, anxiety, sadness, and disappointment. The model is based on the expectancy-disconfirmation theory (Oliver, 1997), regulatory-focus theory (Higgins, 1997, 2001), and appraisal theory of emotions (Lazarus, 1991; Roseman, 1991). The improved conceptual model is shown in Figure 1. The main hypotheses developed later in this paper are shown in the diagram to capture the relationships among design, emotions, word-of-mouth, and repurchase intentions. This hedonic-utilitarian benefits consumption framework helps us understand the differences in hedonic and utilitarian benefits in evoking various types of negative and positive post-consumption emotions. Chitturi et al. (2008) define positive emotions experienced by the consumers when their promotion goals are fulfilled during product consumption as positive promotion emotions. Positive emotions experienced by consumers when their prevention goals are fulfilled during product consumption are defined as positive prevention emotions.

Figure 1. The conceptual framework of choice involving tradeoffs between hedonic and utilitarian design benefits and

post-consumption negative and positive emotions.

Consistent with the conceptual framework for positive promotion and prevention emotions developed by Chitturi et al. (2008), this paper enhances it to define the role of negative promotion and prevention emotions as well. Therefore, we ask the following question: What is the emotional content of the negative consumption experience in the context of the tradeoffs made by the consumer between hedonic and utilitarian design benefits? The conceptual framework posits that the negative consumption experience with a product choice that offers superior utilitarian and inferior hedonic benefits compared to the foregone alternative evokes emotions of sadness, disappointment, and anger; whereas, the negative consumption experience with a product choice that offers superior hedonic and inferior utilitarian benefits compared to the foregone alternative evokes emotions of guilt and anxiety. Further, these post-consumption negative and positive emotions determine the customer loyalty behavior as measured by word of mouth and repurchase intentions (Jacoby & Chestnut 1978). This research empirically validates the proposed relationships in the model shown in Figure 1.

Expectancy Disconfirmation and Emotions

The type and intensity of post-consumption negative emotions are a function of the degree of expectancy disconfirmation and the source (i.e., hedonic versus utilitarian design benefits) of expectancy disconfirmation (Oliver, 1997). The model proposed and tested by Chitturi et al. (2008) comprehensively studies the mixed set of positive emotions that result from such expectancy confirmation along the hedonic and utilitarian benefit dimensions. However, it is relatively silent on the negative set of mixed emotions resulting from such expectancy disconfirmation. This paper develops theoretical bases for a set of four new negative emotions resulting from expectancy disconfirmation with hedonic and utilitarian design benefits. As shown in Figure 1, the enhanced model’s new set of negative emotions are guilt, anxiety, sadness, and disappointment.

Prevention Goals, Promotion Goals, and Negative Emotions

It is known that consumers experience negative emotions when products fail to meet expectations (Mano & Oliver, 1993; Westbrook, 1987). This research adds the following qualification to this general rule: The failure to meet a utilitarian expectation leads to negative prevention emotions of anxiety and anger, whereas the failure to meet a hedonic expectation merely leads to negative promotion emotions of sadness and disappointment. Prior work has shown that prevention goals are considered more important than promotion goals (Chitturi et al., 2007; see also Kivetz & Simonson, 2002b). As such, when a product fails to fulfill a relatively more important prevention goal from utilitarian design features such as anti-lock brakes or safety airbags in a car, consumers are likely to experience intense negative emotions that are high in arousal (Lazarus, 1991; Roseman, 1991). It is expected that this emotion would be related to anger and anxiety for two reasons. First, according to the principle of precedence, consumers expect to fulfill their prevention goals based on the promises of superior utilitarian benefits by the manufacturer (Chitturi et al., 2007). Any failure on the part of the product to meet prevention goals due to disconfirming experience with utilitarian benefits is more likely to be attributed to others (e.g., the manufacturer or retailer) than to the consumers themselves. The appraisal theory of emotions suggests that negative outcomes attributed to others are likely to lead to anger (Roseman, 1991). Second, if consumers choose a product that offers superior utilitarian benefits and inferior hedonic benefits over a foregone alternative with superior hedonics, there is a sense of sadness and disappointment due to an anticipated loss of pleasure as a result of this tradeoff (Chitturi et al., 2007). This discussion leads to the following hypothesis:

- H1: Choosing a product that offers superior utilitarian and inferior hedonic design benefits over a foregone product alternative with superior hedonic and inferior utilitarian benefits, and having a negative consumption experience with the chosen product evokes,

- negative promotion emotions of sadness and disappointment due to a feeling of loss of pleasure from forgone hedonics

- negative prevention emotion of anger due to non-fulfillment of prevention goals from disconfirmation of promised superior utilitarian benefits by the manufacturer

In contrast to the anger evoked by the failure to meet prevention goals from utilitarian design benefits, when consumers tradeoff utilitarian design benefits in favor of hedonic design benefits, does it evoke a different set of negative emotions? Choosing a product that offers superior hedonic and inferior utilitarian design benefits over the foregone alternative also evokes a combination of negative promotion and prevention emotions of guilt and anxiety respectively. Consumers have a sense of guilt when they compromise on utilitarian design benefits and choose a product with superior hedonic and inferior utilitarian design benefits (Kivetz & Simonson, 2002b). This feeling of guilt is magnified when consumption experience is disconfirming on the hedonic dimension and promotion goals are not fulfilled, and when consumption experience is disconfirming on the utilitarian dimension as well. Okada (2005) has shown that the ability to justify hedonic consumption reduces guilt associated with it. In this case, a confirming consumption experience with the utilitarian design benefits would have offered a justification for choosing a hedonically superior product. However, a disconfirming consumption experience on the utilitarian dimension eliminates this possibility—leading to greater intensity of guilt. Further, customers feel anxious about non-fulfillment of minimum prevention goals due to disconfirming consumption experience with utilitarian design benefits. This discussion leads to the following hypothesis:

- H2: Choosing a product that offers superior hedonic and inferior utilitarian design benefits over a foregone product alternative with superior utilitarian and inferior hedonic design benefits, and having a negative consumption experience with the chosen product evokes,

- negative promotion emotion of guilt due to a sense of “yielding to temptation” for superior hedonic benefits at the expense of utilitarian benefits

- negative prevention emotion of anxiety from inadequate utilitarian benefits

Utilitarian Design Benefits and Positive Prevention Emotions, and Hedonic Design Benefits and Positive Promotion Emotions

Thus far, the literature review has generated predictions about the types of negative emotions that are likely to be evoked by the non-fulfillment of prevention and promotion goals from utilitarian and hedonic benefits, respectively. A question that naturally follows is, what types of positive emotions are evoked in post-consumption contexts when the consumption experience meets or exceeds expectations? To offer a comprehensive overview of the enhanced model, this paper discusses hypotheses development and replicates the research study done by Chitturi et al. (2008) on the set of post-consumption positive emotions.

What are the positive emotions that result from the fulfillment of prevention and promotion goals? This research proposes that the type of positive emotion experienced depends on whether a utilitarian or a hedonic expectation of product performance is met. To understand why this is so, consider the differences in the basic characteristics of the goals associated with the utilitarian and hedonic dimensions of product design benefits that was reviewed earlier. The “must-meet” nature of prevention goals increases customers’ focus on the utilitarian benefits of a product because it has been shown that utilitarian benefits are perceived as being closer to necessities or needs that help fulfill prevention goals (Chernev, 2004; Higgins, 1997; Kivetz & Simonson, 2002b). However, when prevention goals are not fulfilled, customers experience increased pain in the form of negative feelings. For example, customer awareness that the absence of air bags and seat belts in a car could lead to severe injury in the event of a car accident is likely to evoke anxiety whenever the customer is in a fast-moving car. The presence of safety features, such as air bags, antilock brakes, and vehicle stability assist, reduces the pain of anxiety and increases feelings of security and confidence. Conversely, the “aspire-to-meet” nature of the promotion goals increases customers’ focus on the hedonic benefits of a product (Chernev, 2004). However, unlike the case of prevention goals, the non-fulfillment of promotion goals is perceived as a loss of pleasure rather than an increase in pain. It is because hedonic benefits are perceived as being closer to luxuries or wants that help fulfill promotion goals (Chernev, 2004; Chitturi et al., 2007; Higgins, 1997; Kivetz & Simonson, 2002b). A loss of pleasure is likely to evoke sadness and disappointment, but an increase in pain is likely to cause anger. For example, driving a convertible along the beautiful Hawaiian coast on a sunny day is likely to be cheerful, exciting, and delightful leading to enhanced pleasure. However, driving a car without a convertible top is unlikely to be painful, though it could be sad and disappointing leading to an overall dissatisfactory experience. Therefore, consistent with Chernev (2004), Chitturi et al. (2007), and Higgins (1997, 2001), the fulfillment of promotion goals by hedonic benefits is likely to evoke feelings of cheerfulness, excitement, and delight, and the fulfillment of prevention goals by utilitarian benefits is likely to evoke feelings of confidence and security.

- H3: A positive consumption experience with utilitarian design benefits evokes greater positive prevention emotions of confidence and security whereas a positive consumption experience with hedonic design benefits evokes greater positive promotion emotions of cheerfulness, excitement, and delight.

Emotional Content of Consumption Experience and Customer Loyalty

An analysis of the emotional consequences of the fulfillment and non-fulfillment of hedonic and utilitarian goals would be beneficial to theory development. It is also managerially relevant because it helps predict post-consumption customer loyalty. Because our primary goal is to understand how the promotion-focused and prevention-focused emotions influence customer loyalty, we will examine how they influence two variables associated with loyalty: word of mouth and repurchase intentions (Jacoby and Chestnut 1978).

Positive Promotion/prevention Emotions, Word of Mouth, and Repurchase Intentions

According to psycho-evolutionary theories of emotion (Frijda, 1987; Lazarus, 1991; Plutchik, 1980), different emotions are associated with different action tendencies (Frijda, 1987). For example, the action tendency associated with anger is one of “boiling inwardly” with a desire to act, whereas that associated with sadness is one of feeling “helpless” (Frijda, 1986). Building on previous research (e.g., Mehrabian & Russell, 1974), this paper argues that the likelihood that an action tendency will be translated into actual behavior depends on the level of arousal associated with the emotion in question. The promotion emotions of cheerfulness, excitement, and delight arising from the fulfillment of promotion goals by hedonic benefits are high-arousal feelings (Lazarus, 1991; Roseman, 1991). They are also the feelings that enhance pleasure accompanied by high arousal. Conversely, the fulfillment of prevention goals by utilitarian benefits leads to the low-arousal feelings of confidence and security (Higgins, 1997; Lazarus, 1991). They are also the feelings that result from reduction in pain that is accompanied by lower arousal.

- H4: Consumers are more likely to indulge in both positive word of mouth and repeat purchase behavior when they experience positive promotion emotions from consumption of hedonic design benefits compared to when they experience positive prevention emotions from consumption of utilitarian design benefits.

Negative Promotion/prevention Emotions, Repurchase Intentions, and Word of Mouth

Thus far, the article has argued that customers with positive promotion (versus prevention) emotions are more likely to express positive word of mouth and indicate intentions of repeat purchase. What happens when the consumption experience is negative?

Based on prior research in marketing, Chitturi et al. (2007) argue that there is a conceptual parallel between necessities–needs–utilitarian benefits and luxuries–wants–hedonic benefits (Chernev, 2004; Higgins, 1997; Kivetz & Simonson, 2002b). In addition, Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy of needs and the precedence principle both position necessities–needs–utilitarian benefits as greater in importance than luxuries–wants–hedonic benefits. Chitturi et al. (2007) show that consumers are focused more on the utilitarian benefits than on the hedonic benefits of a product until their minimum expectations of fulfilling prevention goals are met. Therefore, frustration of prevention goals by utilitarian design benefits evokes anxiety. Furthermore, a utilitarian benefit is a promise of a certain level of functionality by the manufacturer or the retailer. When this promise is not fulfilled, customers blame the retailer and/or the manufacturer. When negative feelings are attributable to an entity, customers feel angry (Lazarus, 1991; Roseman, 1991). Therefore, non-fulfillment of prevention goals due to inadequate utilitarian design benefits makes consumers feel greater anger that is accompanied with greater action tendencies. However, in the case of hedonic benefits such as style and visual appeal, “what you see is what you get.” The customer, not the manufacturer, determines at the time of purchase whether the product is stylish and attractive. Under such circumstances, customers are more likely to blame themselves than the manufacturer if their friends do not find the product to be as “cool” as expected. However, choosing a product with superior hedonic design over one with superior utilitarian design also generates feeling of guilt due to violation of precedence principle (Chitturi et al. 2007; Kivetz & Simonson, 2002b). Therefore, not meeting minimum utilitarian expectations from a functionally superior product choice generates much more intense negative feelings, such as anger, than a less intense feeling such as guilt that results from the choice and non-performance of a hedonically superior product. Because negative prevention emotion of anger is accompanied by higher levels of arousal than negative promotion emotions of guilt, it is expected that the failure of products to meet utilitarian (versus hedonic) expectations leads to greater negative word of mouth and lower repurchase intentions.

- H5: Consumers are (a) more likely to indulge in negative word of mouth and (b) less likely to engage in repeat purchase when the utilitarian design benefits do not fulfill prevention goals evoking negative prevention emotions compared to when the hedonic design benefits do not fulfill promotion goals evoking negative promotion emotions.

Overview of Studies and Results

Through two studies using the consumer products of cell phones and cars, this research shows that the hedonic and utilitarian benefits of a product differ in their ability to evoke positive and negative promotion and prevention emotions. The products were selected to ensure that participants would be familiar with their attributes and benefits, and could imagine the set of products in various usage scenarios. At the same time, it was important that the chosen products be both visible and useful to enhance the relevance of both the hedonic and the utilitarian benefits. The first study with imagined cell phone consumption scenarios involved student participants at a North American university for extra credit. The second study was conducted with student automobile owners to tap into real feelings based on real consumption experience.

Study 1

Design and Task

We used a 2 (product design benefits2: hedonic versus utilitarian) x 4 (consumption experience: confirm/confirm, confirm/disconfirm, disconfirm/confirm, disconfirm/disconfirm) between-subjects design. A total of 240 undergraduate students participated for extra credit. The participants were randomly assigned to each of the eight cell phones. Participants were given a booklet titled “Consumer Decision Making Questionnaire,” with the following starting instructions on the first page:

In this questionnaire, we are interested in finding how you feel about a product after its purchase and consumption. In the following pages, you will read about two scenarios that describe your needs, attributes of a chosen product, and subsequent consumption experience. Please read the two scenarios carefully and respond to the questions that follow.

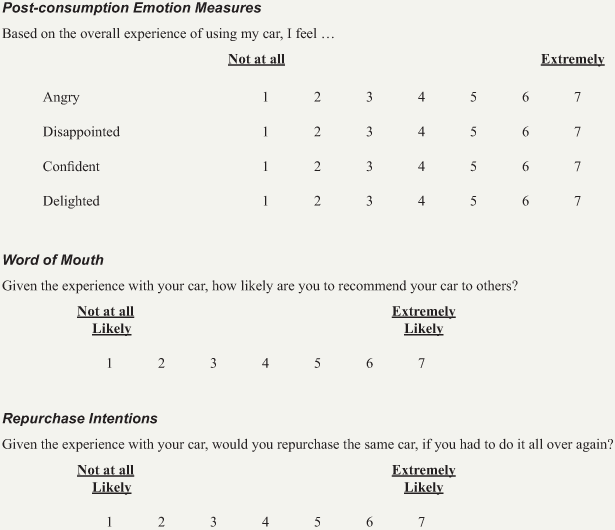

On the following page, participants read information about the two cell phone choices. Each cell phone was described as a combination of the three hedonic and three utilitarian attributes. One of the cell phones offered a “high” level of three hedonic attributes and a “medium” level of three utilitarian attributes. The other cell phone in the choice set offered a “medium” level of three hedonic attributes and a “high” level of three utilitarian attributes. These three hedonic and three utilitarian attributes were presented with a picture of the cell phone. Each of the six attributes and the cell phone picture had two levels and associated consumption benefits—high and medium. The group of attributes offering benefits—hedonic or utilitarian—labeled as “high” was given a Consumer Reports rating of 4.5 out of 5, and the group labeled as “medium” was given a Consumer Reports rating of 3.0 out of 5. After reviewing the information and the picture of each cell phone, participants were asked to read two product choice and consumption scenarios. The first scenario described the purchase and subsequent consumption experience with one of the cell phones, and the second scenario described the purchase and subsequent consumption experience with the other cell phone. The consumption experience within a group condition was the same across the two scenarios. Only the cell phone choice (hedonic versus utilitarian) changed between the two scenarios. The participants were then told to imagine themselves in the first scenario, and they answered questions about how they would feel in that situation. They reported their level of feelings on a total of 14 anchor measures of discrete positive and negative emotions. They rated 14 emotions (i.e., guilt, anxiety, sadness, dissatisfaction, regret, anger, disappointment, surprise, security, confidence, excitement, satisfaction, cheerfulness, and delight) with the following instructions: “Based on the overall experience of using my current product, I feel …” (seven-point scale anchored by 1 = “not at all” and 7 = “extremely”; for sample measures, see Appendix). This was followed by a four-item scale that measured arousal (Mehrabian and Russell 1974). The four-item scale included measures comprising stimulated/relaxed, excited/calm, aroused/unaroused, and jittery/dull. Participants then answered questions about positive word of mouth, negative word of mouth, and repurchase intentions (for sample measures, see Appendix). These measures of emotions, word of mouth, and repurchase intentions served as dependent variables across the treatment conditions. Finally, participants completed the section containing manipulation checks and demographic variables.

Stimuli Construction

The objective was to construct more realistic stimuli while retaining the level of control that is needed to test the hypotheses. To accomplish this objective, we conducted two pretests. For Pretest 1, a comprehensive list of attributes was developed based on real product manuals of some of the most popular cell phones in the market (e.g., Nokia, Samsung, and Motorola). This led to a list of more than 50 attributes. For practical reasons, the goal was to identify the top three most influential attributes that offer hedonic benefits and the top three most influential attributes that offer utilitarian benefits to construct the stimuli for the experiment. To accomplish this, more than 100 participants were asked to rate all the attributes in terms of importance and impact on purchase decision3. On the basis of the Pretest 1 responses, the top 15 most influential attributes on purchase decision were selected. To test our theory, product stimuli were constructed that had either a group of attributes that was primarily hedonic, or a group that was primarily utilitarian in terms of the benefits offered.

Stimuli Description

The utilitarian benefits dimension of each cell phone comprised the level of network coverage (98% versus 95%), battery capacity (three days versus two days), and sound clarity (high versus medium). The hedonic benefits dimension comprised the oyster flip phone feature (yes/no), the option to change phone colors (yes/no), and the ability to program new ring tones (yes/no). These attribute descriptions and levels were combined with pictures of the two cell phones. One picture showed a highly stylish and attractive oyster flip phone, and the other showed a medium-rated non-flip feature cell phone.

Manipulation Checks

On a seven-point scale, participants indicated the extent to which the consumption experience met their expectations on the hedonic dimension (1 = “better than expected,” and 7 = “worse than expected”). The same question was repeated for the utilitarian dimension. The measures were reverse coded for data analysis. The t-tests showed that the manipulation was successful. The means for the four experience conditions for the product with superior hedonic benefits were (1) confirm/confirm = 5.84/4.96, (2) disconfirm/disconfirm = 2.8/2.32, (3) confirm/disconfirm = 5.18/2.43, and (4) disconfirm/confirm = 3.1/4.61. Similarly, the means for the four experience conditions for the product with superior utilitarian benefits were (1) confirm/confirm = 5.27/5.56, (2) disconfirm/disconfirm = 2.73/2.51, (3) confirm/disconfirm = 4.98/2.77, and (4) disconfirm/confirm = 2.4/5.11.

Results and Discussion

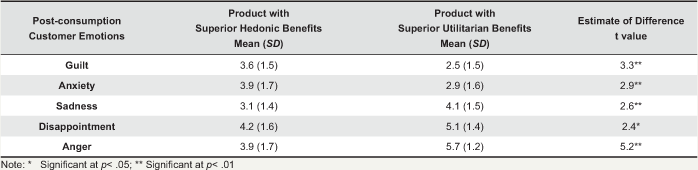

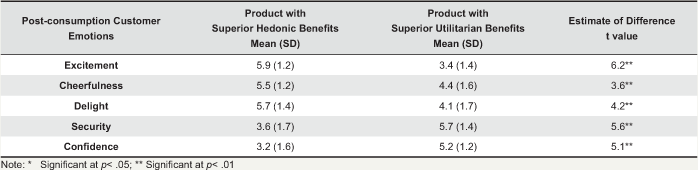

To test H1 and H2, we ran a MANOVA across two product types for the emotions of guilt, anxiety, sadness, disappointment, and anger. The results for the two product-type groups were significant (Wilks’ l = .903, F = 12.518, p < .01), and the univariate tests for guilt, anxiety, sadness, disappointment, and anger were also significant (tguilt = 3.3, p < .01; tanxiety = 2.9, p < .01; tsadness = 2.6, p < .01; tdisappointment = 2.4, p < .05; tanger = 5.2, p < .01). The cell means and standard deviations for all the negative emotions as a result of negative consumption experience with a cell phone with superior hedonic benefits versus superior utilitarian benefits appear in Table 1. To test H3, we ran a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) across four experience conditions and two product types (superior hedonic benefits versus superior utilitarian benefits) for prevention emotions of confidence and security and promotion emotions of excitement, cheerfulness, and delight. The results from the MANOVA were significant for product type (Wilks’ l = .605, F = 37.389, p < .01) and experience (Wilks’ l = .510, F = 14.69, p < .01), and the univariate tests for cheerfulness, excitement, delight, confidence, and security were significant as well (p < .05). The cell means and standard deviations for all the positive emotions as a result of positive consumption experience with a cell phone with superior hedonic benefits versus superior utilitarian benefits appear in Table 2. A two-sample t-test found that in the case of a positive consumption experience, consumers feel greater intensity of excitement, cheerfulness, and delight with a more hedonic cell phone than with a more utilitarian cell phone (texcitement = 6.2, p < .01; tcheerfulness = 3.6, p < .01; tdelight = 4.2, p < .01). Conversely, a positive experience with a utilitarian cell phone leads to greater security and confidence (tsecurity = 5.6, p < .01; tconfidence = 5.1, p < .01). The result with cell phones is consistent with our predictions in H3. The findings about customer emotions show that the results are significant and in the right direction; hedonic cell phones are better at fulfilling promotion-focused emotional goals, and utilitarian cell phones are better at fulfilling prevention-focused emotional goals (Chernev, 2004; Higgins, 2001).

Table 1. Post-consumption emotional responses for negative experience with hedonic versus utilitarian product benefits (cell phone study 1)

Table 2. Post-consumption emotional responses for positive experience with hedonic versus utilitarian product benefits (cell phone study 1)

Next, in terms of H4 and H5, we need to determine whether differences in hedonic versus utilitarian product benefits and the emotions elicited in the positive or negative consumption experience are also accompanied by significantly different levels of arousal, positive word of mouth, negative word of mouth, and repurchase intentions. The two-sample t-test shows that customers experience greater arousal with the hedonic cell phone than with the utilitarian cell phone (tarousal = 4.10, p < .01). The two-sample t-test shows that customers are more likely to indulge in positive word-of-mouth behavior and have greater repurchase intentions in the case of positive consumption experience with a hedonic cell phone than with a utilitarian cell phone (tWOM = 5.19, p < .01; tRPI = 4.73, p < .01). Conversely, consumers experience greater arousal with a utilitarian cell phone than with a hedonic one in the case of negative consumption experience (tarousal = 3.54, p < .01). Therefore, as we expected, consumers are more likely to indulge in negative word-of-mouth behavior and have less repurchase intentions with a utilitarian cell phone than with a hedonic cell phone (tNWOM = 4.90, p < .01; tLRPI = 3.70, p < .01). This demonstrates that the consumption of hedonic versus utilitarian benefits offered by a product indeed generates significantly different intensities of post-consumption emotions and is accompanied by higher levels of positive (or negative) word of mouth and repurchase intentions when the experience is positive (or negative).

Study 2

We conducted Study 1 and measured consumption emotions and loyalty based on imagined experience scenarios rather than real experiences. To address this issue and to improve the external validity, we conducted Study 2 with undergraduate students who are car owners with real experiences. We measured the same set of 14 dependent measures of post-consumption emotions and customer loyalty on the basis of their real experience with their car. The results are consistent with the findings in Study 1, and they provide additional insights into our research question.

Design and Task

We designed the questionnaire to collect information about student car owners’ feelings about their car based on their consumption experience. A total of 112 student car owners participated in the study. They rated 14 emotions (i.e., guilt, anxiety, sadness, dissatisfaction, regret, anger, disappointment, surprise, security, confidence, excitement, satisfaction, cheerfulness, and delight) in response to the statement, “Based on the overall experience of using my current car, I feel,…” on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 = “not at all” to 7 = “extremely” (for sample measures, see Appendix). After the emotion measures, the participants rated how likely they would be to recommend their car to others (as a measure of the positive word of mouth) and how likely they would be to repurchase this car if they were to do it all over again. We measured word of mouth and repurchase intentions on a seven point scale ranging from 1 = “not at all likely” to 7 = “extremely likely.” This was followed by participants’ overall impression of the product on the hedonic dimension of “style and attractiveness” and the utilitarian dimension of “functionality” on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 = “not at all impressive” to 7 = “extremely impressive,” as well as by a four-item measure of arousal (Mehrabian & Russell 1974). Participants then answered questions about whether the product met their expectations on the “style and attractiveness” and “functionality” dimensions. Finally, participants provided demographic information.

Results and Discussion

On the basis of the median split of participants’ responses on the overall rating of “style and attractiveness” and “functionality” of their cars, we created four groups (i.e., 1 = high/high, 2 = low/low, 3 = high/low, and 4 = low/high). The results for emotions from a MANOVA were significant for the four group conditions (Wilks’ l = .521, F = 2.11, p < .01), and the univariate tests for all emotions except guilt, anxiety, and surprise were significant as well (p < .05). Our primary focus in this study is to identify the differences in the antecedents of positive promotion and positive prevention emotions resulting from the respective consumption of products with superior hedonic benefits and superior utilitarian benefits. Adapting the approach taken by Higgins (1997, 2001) and Chitturi et al. (2008), we grouped the emotions of confidence and security by averaging them to form a measure of positive prevention emotions and by averaging the emotions of excitement, cheerfulness, and delight to form a measure of positive promotion emotions.

We replicated and tested a full model of positive promotion and prevention emotions that was proposed and tested by Chitturi et al. (2008). The model studies the relationship between hedonic and utilitarian benefits with loyalty, as measured by word of mouth and repurchase intentions. Although positive promotion and positive prevention emotions are positively correlated (a = .57), we also found evidence that there are significant differences between them. The discussion of the results of our analysis follows.

A full model tests the proposed relationships among promotion emotions and loyalty, as measured by word of mouth and repurchase intentions, using mediation analysis (Baron & Kenny, 1986). A full model also tests the proposed relationships among prevention emotions, word of mouth, and repurchase intentions. The results show that both promotion and prevention emotions directly influence word of mouth (βpromotion = .180, p < .05; βprevention = .492, p < .000; adjusted R2 = .276), and promotion emotions significantly improve word of mouth in addition to prevention emotions. Similarly, both promotion and prevention emotions directly influence repurchase intentions (βpromotion = .287, p < .029; βprevention = .632, p < .000; adjusted R2 = .364), and promotion emotions significantly improve repurchase intentions in addition to prevention emotions. The results demonstrate that promotion emotions improve customer loyalty by improving word of mouth and repurchase intentions. However, what about the role of hedonic versus utilitarian design benefits in evoking promotion versus prevention customer emotions? Further analysis of the relationship among design benefits, promotion emotions, and prevention emotions reveals that only hedonic benefits influence promotion emotions (βutilitarian = .054, n.s.; βhedonic = .372, p < .000; adjusted R2 = .189), whereas both hedonic and utilitarian benefits influence prevention emotions. As we predicted, utilitarian benefits have a greater influence on prevention emotions than hedonic benefits (βutilitarian = .422, p < .000; βhedonic = .201, p < .023; adjusted R2 = .231). As we discussed previously, the results show a stronger association of hedonic benefits with promotion emotions, and a stronger association of utilitarian benefits with prevention emotions.

General Discussion

Design is a planned organization of elements in a domain, interconnected with a specific purpose. The purpose of a design could be to create a right mix of positive and/or negative emotional experiences for the consumers. Further, based on our own experiences with physical products, we know that product designs can be emotional (Norman, 2004). However, designers would like to know if different designs elicit different types and intensities of emotions (Chitturi et al., 2007, 2008). On the other hand, customers purchase products to either minimize pain or maximize pleasure, or both. Between enhancing pleasure and reducing pain there are many different mixes of the types and intensities of positive and negative emotions that are a part of the consumption experience. Developing a marketing driven design benefits framework would improve our understanding of the consumption motivations of customers. This is critical to improving the effectiveness of a designed product. To this end, this article adapts the conceptual framework of hedonic/utilitarian design benefits and consumption experience proposed by Chitturi et al. (2008) to include the negative as well as positive emotional content of the consumption experience.

In this article, we studied and found evidence for the research model proposed by Chitturi et al. (2008) where the type and the intensity of the emotional experience arising from the consumption of hedonic benefits are qualitatively different from those of utilitarian benefits. This paper enhances the model by including results for the four new negative emotions of guilt, anxiety, sadness, and disappointment with the original model by Chitturi et al. (2008). The differences in the emotional content of the consumption experience result in different levels of negative promotion emotions, negative prevention emotions, negative word of mouth, and lower repurchase intentions. The article explored this question with studies involving cell phones and automobiles. Study 1 involved students in North America with imagined scenarios. Study 2 involved student automobile owners and tapped into their real consumption experiences. The results across the two studies are consistent and support the fundamental research proposition and the proposed enhanced model (see Figure 1).

Hedonic and Utilitarian Design Benefits and Emotions

Building on the work of Higgins (1997, 2001), Chernev (2004), and Chitturi et al. (2007), we proposed that the goals of a prevention focus served by utilitarian benefits are primarily to avoid pain, whereas the goals of a promotion focus served by hedonic benefits are primarily to seek pleasure. Consistent with the predictions, the results show that the type and the intensity of consumption emotions differ between hedonic and utilitarian benefits because they help fulfill different goals of seeking pleasure and avoiding pain. The result from the first study proves a correspondence that links utilitarian design benefits with the negative prevention emotions of anxiety and anger. Likewise, the results show correspondence that links hedonic design benefits with the negative promotion emotions of guilt, sadness and disappointment, leading to lower customer loyalty. Furthermore, in the case of a positive consumption experience, the results from the second study point to a correspondence that links hedonic design benefits with the positive promotion emotions of cheerfulness, excitement, and delight, and a correspondence that links utilitarian design benefits with the positive prevention emotions of confidence and security, both leading to greater word-of-mouth and repurchase intentions.

The research findings in this article could have significant implications for decision makers in product design and marketing organizations. Because of budget and time constraints, designers and managers are often compelled to choose among various attributes. If there is no budget or time constraints, perhaps the best solution is to maximize both hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of benefit. What are the economic constraints and customer preference patterns based on tradeoffs involving hedonic and utilitarian design benefits? Does it lead to significant differences in the diffusion of innovations? These are potential topics for further research. These unknowns make the tradeoff process between various attributes and benefits difficult and non-optimal (Chitturi et al., 2007). However, more often than not, product designers and managers are forced to tradeoff between selecting one attribute or another for various reasons. In such situations, we believe that the designers and marketing managers would be able to make better decisions if they considered both the negative and the positive emotional consequences of tradeoffs.

Design Strategy, Emotions, and Loyalty

How can designers, engineers, and marketers benefit from the enhanced model presented in this paper? The presence of a variety of post-consumption negative emotions resulting from a tradeoff decision and negative experience suggests the following. First, the effectiveness of a design strategy in influencing customer behavior is as much a function of the forgone product alternative as it is of the design of the product itself. Additionally, expectancy disconfirmation from hedonic and utilitarian benefits consumption evokes different types and intensities of negative emotions (i.e., guilt, anxiety, sadness, disappointment, and anger). Based on the enhanced model in the paper, the process of product development and testing can be made much more benefits–experience–emotion centric than purely attribute-centric by including the following steps: (1) Rate every attribute being considered for inclusion in the design specification on its ability and likelihood of fulfilling target customers’ promotion and prevention emotional wants and needs; (2) use conjoint analysis to identify the most desirable combination of the promotion and prevention emotions and their relative influence on customer loyalty; (3) calibrate and match the attributes on the basis of their contribution rating on promotion and prevention emotions from Step 1 with the ideal combination of promotion and prevention emotions for the target customer segment from Step 2; and (4) iteratively calibrate concept testing, product use testing, and market testing with the ideal profile of promotion and prevention emotions developed in Steps 1, 2, and 3 until an optimal product and marketing plan is achieved. It is more beneficial to base design decisions on consumer emotions because emotions are a better predictor of consumer behavior than attribute levels designed into the product. The same level of attributes can evoke different intensities of specific emotions, therefore bringing about error when mapping attribute levels directly to predict consumer behavior without incorporating the effect of emotional intensities on consumer behavior. The incorporation of these steps into the new product design and development process will improve the probability of success for a new product.

Conclusion

On the basis of the results from our studies, we recommend that designers and marketers understand the full breadth and depth of the positive and negative promotion and prevention emotions of consumers. Designers should also be aware that these emotions come from the consumption of hedonic and utilitarian design benefits offered by a product, as well as from the knowledge of the forgone product alternative. Application of the insights developed in this research could potentially help firms in formulating their design strategy to improve customer loyalty and consequent return on investment.

Endnotes

1 Voss, Spangenberg, and Grohmann (2003, p. 310, emphasis added) state, “Investigation of the hedonic and utilitarian components of attitude has been suggested in such diverse disciplines as sociology, psychology, and economics. This multidisciplinary recognition of the hedonic and utilitarian elements of consumption mirrors parallel theoretical development in marketing, mainly from a series of articles (e.g., Batra & Ahtola 1990; Chitturi et al. 2007; Dhar & Wertenbroch 2000; Okada 2005).”

2 The benefits offered by the attributes of a product can be broadly categorized along two dimensions: hedonic and utilitarian. These benefits can be high or low, depending on the product (Crowley, Spangenberg, and Hughes 1992). Consistent with the work of Dhar and Wertenbroch (2000) and Okada (2005), this research conceptualizes hedonic (or utilitarian) product alternatives as ones that offer relatively superior hedonic (or superior utilitarian) benefits compared to the foregone alternative(s) in the choice set.

3 Single-item discrete emotion measures are prevalent in emotion literature. For a more detailed discussion, see Larsen and Fredrickson (1999, pp. 40-60). For a more detailed discussion on the effectiveness of single-item versus multi-item measures, see Bergkvist and Rossiter (2007).

Reference

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173-1182.

- Batra, R., & Ahtola, O. T. (1990). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes. Marketing Letters, 2(2), 159-170.

- Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. (2007). The predictive validity of the multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(2), 175-184.

- Chernev, A. (2004). Goal-attribute compatibility in consumer choice. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(1-2), 141-150.

- Chitturi, R., Raghunathan, R., & Mahajan, V. (2007). Form versus function: How the intensities of specific emotions evoked in functional versus hedonic trade-offs mediate product preferences. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(4), 702-714.

- Chitturi, R., Raghunathan, R., & Mahajan, V. (2008). Delight by design: The role of hedonic versus utilitarian benefits. Journal of Marketing, 72(3), 48-63.

- Crowley, A. E., Spangenberg, E. R., & Hughes, K. R. (1992). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of attitudes toward product category. Marketing Letters, 3(3), 239-249.

- Desmet, P. M. A., & Hekkert, P. (2007). Framework of product experience. International Journal of Design, 1(1), 57-66.

- Dhar, R., & Wertenbroch, K. (2000). Consumer choice between hedonic and utilitarian goods. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(1), 60-71.

- Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Frijda, N. H. (1987). Emotion, cognitive structure, and action tendency. Cognition and Emotion, 1(2), 115-143.

- Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52(12), 1280-1300.

- Higgins, E. T. (2001). Promotion and prevention experiences: Relating emotions to nonemotional motivational states. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Handbook of affect and social cognition (pp. 186-211). London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Jacoby, J., & Chestnut, R. W. (1978). Brand loyalty: Measurement and management. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Kivetz, R., & Simonson, I. (2002a). Earning the right to indulge: Effort as a determinant of customer preferences toward frequency program rewards. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(2), 155-170.

- Kivetz, R., & Simonson, I. (2002b). Self-control for the righteous: Toward a theory of precommitment to indulgence. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(2), 199-217.

- Larsen, R, J., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1999). Measurement issues in emotion research. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundation of hedonic psychology (pp. 40-60). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mano, H., & Oliver, R. L. (1993). Assessing the dimensionality and structure of consumption experience: Evaluation, feeling, and satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(3), 451-466.

- Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper and Row.

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Norman, D. A. (2004). Emotional design: Why we love (or hate) everyday things. New York: Basic Books.

- Okada, E. M. (2005). Justification effects on consumer choice of hedonic and utilitarian goods. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(1), 43-53.

- Oliver, R. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Plutchik, R. (1980). Emotion: A psychoevolutionary synthesis. New York: Harper and Row.

- Postrel, V. (2003). The substance of style. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Roseman, I. J. (1991). Appraisal determinants of discrete emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 5(3), 161-200.

- Strahilevitz, M., & Myers, J. G. (1998). Donations to charity as purchase incentives: How well they work may depend on what you are trying to sell. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(4), 434-446.

- Voss, K. E., Spangenberg, E. R., & Grohman, B. (2003). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(3), 310-320.

- Westbrook, R. A. (1987). Product/consumption-based affective responses and postpurchase processes. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(3), 258-270.

Appendix —

Sample Items From Study Measures