Institutioning as Action: Mediating Grassroots Labor and Government Work for Sustainable Transitions

Liesbeth Huybrechts 1,*, Dolores Van den Eynde 1, Gasper Kabendela 1,2,3, Elke Knapen 1,

Janepher Shedrack Kimaro 1,2,3, and Fredrick Magina 2

1 UHasselt, Hasselt, Belgium

2 Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

3 Institute of Rural Development Planning, Dodoma, Tanzania

Public governments charged with overseeing sustainable urban transitions face multiple challenges stemming from limited resources, means, and time. Addressing such challenges requires innovative approaches that are not typically part of the standard work practices of governmental institutions and often take the form of initiatives originating within grassroots communities. As a result, governments have increasingly recognized the value of engaging with such grassroots initiatives and frequently invite participatory designers to facilitate collaborative activities between public institutions and communities. Conversely, grassroots communities often seek the support of participatory designers to enhance dialogue and foster cooperation with public governments to strengthen their work on the ground. To further explore and better understand how participatory design (PD) methods can support these collaborative efforts—referred to as institutioning—this study combines a literature review with a comparative analysis of two case studies from Tanzania and Belgium. This research provides a framework for field analysis and mediating future institutioning cases in the context of sustainable urban transitions. It also highlights institutioning as a PD process driven by the collective learning that takes place between governments and communities. Furthermore, we present five socio-material mediating actions that encompass interactions across human and more-than-human actors.

Keywords – Grassroots Communities, Institutioning, Participatory Design, Policy Design, Public Institutions, Scarcity.

Relevance to Design Practice – The paper presents an exploratory theoretical analysis of the challenges faced by designers who act as intermediaries facilitating collaborative efforts between grassroots communities and public governments. Their actions offer a framework to support field analysis and inform future participatory engagements based on two active case studies.

Citation: Huybrechts, L., Van den Eynde, D., Kabendela, G., Knapen, E.,Kimaro, J. S., & Magina, F. (2024). Institutioning as action: Mediating grassroots labor and government work for sustainable transitions. International Journal of Design, 18(3), 89-104. https://doi.org/10.57698/v18i3.07

Received May 31, 2024; Accepted November 10, 2024; Published December 31, 2024.

Copyright: © 2024 Huybrechts, Van den Eynde, Kabendela, Knapen, Kimaro & Magina. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: liesbeth.huybrechts@uhasselt.be

Liesbeth Huybrechts is an associate professor with the ArcK research group at Hasselt University, Belgium. Her work focuses on participatory design, design anthropology, and environmental transformation processes, with research interests that include designing for/with participatory exchanges and capacity-building processes between humans and the material/natural environment, as well as examining the implicit “politics” of such relationships.

Dolores Van den Eynde researches political science, participatory design, and policy design at the ArcK research group at Hasselt University, Belgium. With an academic background in international politics and communication studies, her research focuses on understanding, facilitating, and designing processes that enhance public participation.

Gasper Kabendela is a PhD researcher and volunteer research assistant at Hasselt University, Belgium. He is also an assistant lecturer at Tanzania’s Institute of Rural Development Planning in Dodoma and a research fellow at Ardhi University. With a background in Urban and Regional Planning, he has over 10 years of experience working as a town planner with several local government authorities serving various communities. His research primarily focuses on participatory land use planning and conflict resolution techniques.

Elke Knapen is an associate professor and academic coordinator of the Building Beyond Borders program at Hasselt University, where participants engage in participatory design and seek to develop projects with positive social-ecological impacts. Her research focuses on regenerative design combining theoretical knowledge with hands-on experiments and real-world applications.

Janepher Shedrack Kimaro is currently pursuing a PhD in Urban Planning and Management at Ardhi University and Hasselt University in Belgium. She holds a joint Master’s of Regional Development Planning from the Technical University of Dortmund and the University of the Philippines, as well as a BSc in Housing and Infrastructure Planning from Ardhi University. She is an Assistant Lecturer at the School of Spatial Planning and Social Sciences at Ardhi University and a registered town planner with Tanzania’s Town Planners Registration Board. Her research topic is Participatory Planning and Land Use Conflict Management in Demarcated Conflict Areas in Dar es Salaam.

Fredrick Magina is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Spatial Planning and Social Sciences (SSPSS) and the Head of the Department of Urban and Regional Planning (URP). He holds PhD in Urban Planning from TU Dortmund University, Germany. Fredrick has experience in teaching and research particularly on access to land and resource use conflict management, urban housing, regional development planning, participatory land use planning, and regularization of informal settlements.

Introduction: Institutioning in Sustainable Urban Transitions

Public governments responsible for achieving sustainable urban transitions face persistent challenges due to limited resources, means, and time. Addressing these challenges requires innovative approaches, including strategies for responsible resource consumption, land use, livability, and mobility (Besha et al., 2024; Jagtap, 2022). However, novel approaches often depend on the initiatives of grassroots communities, as they do not typically originate in the context of public governments’ usual work practices. When individuals within communities become discontent with the status quo, feeling the direct impact of public policy on their lives (Kaufman, 1997), they are more likely to self-organize, comprising a bottom-up response to solve problems (Smith et al., 2014). Despite this, meaningful engagement with these kinds of grassroots initiatives by public governments is still lacking in the context of sustainable urban transitions (Apostolopoulou et al., 2022).

Nonetheless, public governments have increasingly acknowledged the benefits of engaging with grassroots initiatives, and participatory designers are often invited to facilitate engagement between public governments and grassroots communities (Jagtap, 2022). Conversely, grassroots communities seek the support of participatory designers to strengthen dialogue and collaboration between public institutions and their work on the ground (Huybrechts, Hendriks, et al., 2017). In this context, PD becomes integral to institutioning—practices that integrate the internal and external dynamics inherent in participatory processes by consolidating and challenging existing institutional frameworks, and when necessary, creating new ones (Huybrechts, Benesch, et al., 2017). While mediating between public governments and communities to address public concerns during the sustainable transition process, it is common for participatory designers to become directly involved in such initiatives, and over time, their role within communities has grown significantly (Robertson & Simonsen, 2012). Therefore, the implementation of research and design practices that help public institutions address public concerns has become more prominent (Huybrechts, Benesch, et al., 2017).

However, participatory designers in diverse national and cultural contexts continue to experience multiple challenges when carrying out institutioning actions as they navigate between communities’ grassroots initiatives and public institutions’ sustainable transition processes. These challenges, along with the effective organization of institutioning processes in relation to the dynamics between public governments and grassroots initiatives, remain under-researched. Therefore, this article aims to answer the question, “How can we better articulate and develop institutioning actions that tap into grassroots labor by communities to innovate the work practices of public governments dealing with sustainable transitions in contexts of scarcity?” Such contexts include scarcity both in terms of practical issues such as lack of time and means as well as limited resources on a larger, ecological scale.

To explore possible answers to the above question, we explore two case studies in which participatory designers assume a mediating role between grassroots communities and public governance care activities: (1) the self-organized construction of a road and (2) the building of community infrastructure with urban-harvested materials. These case studies demonstrate how communities actively engage in care work traditionally managed by public institutions. The authors of this article, with backgrounds spanning planning policy, sustainability, and design, are currently part of an international PD research group connecting Belgium and Tanzania to carry out a collaborative VLIR/UOS project (2022-2032) titled “Participatory Sustainable Urban Transitions.” With this background, the article contributes new insights into the role of participatory designers as they navigate public policy within the social and material worlds of communities. In doing so, this paper provides a foundation for understanding the institutioning actions that occur between public governments and communities, along with the challenges and opportunities these present for participatory designers in diverse national and cultural settings.

Unpacking Labor, Work, and Action in Institutioning

Throughout this article, we draw on terminology developed by Arendt (2013) in The Human Condition—particularly labor, work, and action—to articulate the concept of institutioning as it relates to interactions between public governments and grassroots communities. These concepts help to further elucidate three key roles or actors involved in institutioning processes: grassroots communities, public governments, and participatory designers.

Labor, Work, and Action

We focus on three central concepts previously explored in PD research (Huybrechts et al., 2018) and further expand them to better understand the collaborative efforts of public governments and grassroots communities in realizing sustainable urban transitions.

- Labor refers to cyclical activities people undertake to preserve the private lives of households and support the common interests of the community.

- Work refers to the creation of useful outcomes, such as the production of goods in professional settings. It is also based on a linear concept of time, with a clear beginning and end, and measurable effects.

- Action includes the role of active citizens in the public realm who reconnect the spheres of labor and work; that is, daily labor activities within a community support the preservation of life and the professional work domain of public governance.

Arendt’s (2013) terminology helps to clarify the domains in which institutioning processes take place, highlighting the complexity of these processes and identifying obstacles that limit engagement with institutioning practices. It also enables us to articulate political aspects of labor affecting these institutioning processes, which often exist beyond the bounds of the professional work activities undertaken by communities, public governments, and designers (Huybrechts et al., 2018). Although this labor is essential for innovating work practices, it is important to discuss the challenges and advantages of such labor-intensive engagements in the context of sustainable urban design. Establishing actions that connect labor and work is crucial to ensure the labor of communities, public governments, and designers in grassroots community projects is recognized, otherwise such efforts risk being dismissed as unimportant or perceived as too challenging to pursue. In the following literature review and case analysis, we explore actions designers can take to connect the labor of governments and communities and identify opportunities for more innovative work practices.

Three Actors: Grassroots Communities, Public Governments, and Designers

To further articulate institutioning work to address sustainable transitions in the context of scarce resources, we examine three important groups of actors: grassroots communities, public governments, and participatory designers.

Grassroots Communities: Bottom-up Initiatives

Community members dissatisfied with their government’s approach to urban transformation, particularly when it directly and adversely impacts their lives (Kaufman, 1997), may self-organize into a grassroots movement, forming a bottom-up response to address the issue more effectively (Smith et al., 2014). At the local level, community members share common interests and face similar challenges, enabling them to effectively identify shared and unused resources and articulate their needs with greater specificity. This mutual understanding leads to a consolidation of power at the grassroots level, which is often realized through spatial interventions that address problems such as political patronage, bureaucracy, and limited resources. This phenomenon is referred to as “radical grassroots social innovations” (Apostolopoulou et al., 2022), where formal or informal community-led organizations mobilize to address challenges that have otherwise been ignored, enhancing their ability to resolve them in innovative ways.

Public Governments’ Responses: Designing Public Participation

Public governments continue to exhibit a lack of meaningful engagement with grassroots initiatives in the context of sustainable urban transitions (Apostolopoulou et al., 2022). However, public participation within communities continues to grow due to increasing pressure on the model of representative democracy and the need for innovative approaches to deal with urban transitions in contexts of scarcity (Bobbio, 2019; Bussu et al., 2022; Jäntti et al., 2023). Research on public participation began in the 1990s (Kaufman, 1997; Uphoff, 1992), and interest in policy design, rooted in policy studies, has continued to expand (Mortati et al., 2022). This growing interest has led to the use of design as a tool to reorganize public participation, offering a procedural instrument for policymakers to involve new and diverse actors. such as civil society stakeholders (Bobbio, 2019).

However, a meaningful shift toward making public participation a common practice has yet to be achieved, and when design processes fail to integrate participatory activities into policymaking processes, people are likely to question their legitimacy and effectiveness, leading to disappointment (Bobbio, 2019; Jäntti et al., 2023). Similarly, participatory innovations are criticized for failing to connect political institutions and civil society (Bussu et al., 2022). This may result from the way problems are framed differently in policy and design contexts, impacting how they are handled and sometimes resulting in misunderstandings and distrust (van der Bijl-Brouwer, 2019). In addition, policymakers are often unwilling to adopt design approaches within public settings, where rationality and low-risk strategies are typically prioritized (Brinkman et al., 2023). At the same time, PD requires a more comprehensive understanding of contemporary policy mechanisms and the multidirectional nature of community participation (Bason, 2016; Washington, 2023a). This applies to both governments initiating participatory approaches to policymaking and communities seeking to influence public policy.

To deepen our understanding of these phenomena, we examined seven narratives designed to increase policy participation over time, combining our findings with insights drawn from De Smedt and Borch (2022) and Vaz et al. (2022). The most prevalent of these narratives is the evidence-based narrative, which is primarily based on reason, consensus, and knowledge-building to provide evidence-based decision making. Other narratives include the argumentative narrative (in which arguments bridge divides between opponents), the strategic narrative (various strategies provide insight into different interests), the participatory policy narrative (which assumes participants are competent to deliberate on key issues), the negotiation narrative (individuals with opposing views discuss controversial issues) and the co-creation narrative (views are structured as interactive exchanges in the context of work meetings). Finally, the grassroots narrative marks a significant departure from traditional policymaking approaches by offering grassroots actors the opportunity to both initiate and monitor community practices (Vaz et al., 2022). This narrative also most closely aligns with the approach adopted in the cases discussed in this paper. Since this approach to designing policy participation has not yet been widely adopted (Blomkamp, 2018; Vaz et al., 2022), the challenge for PD is to create scenarios in which the labor better aligns with and reflects policy objectives.

Participatory designers can achieve these objectives by understanding how policy capability infrastructures can be challenged and adapted to foster more effective engagement with grassroots initiatives. Specifically, designers need to examine how this infrastructure shapes leadership, policy quality systems, people’s capabilities, and the engagement of diverse publics (Washington, 2023a). To support a shift in this infrastructure, Washington (2023b) advocates for the integration of three capabilities to enhance policymaking systems: “hindsight,” which involves learning from the past to improve transitions, “foresight,” or proactively addressing potential future challenges, and “insight,” which entails a deeper understanding of how policy impacts the world, utilizing data and academic expertise to grasp complex dynamics and interactions.

Participatory Design And Institutioning

Participatory designers who engage deeply with innovative grassroots initiatives have an opportunity to provide valuable insights that can contribute to more sustainable policy decisions and help to identify additional resources supporting reflexive and pluralistic perspectives. Although such cases exist in diverse contexts and cannot always be easily replicated, they nonetheless challenge existing approaches to interacting with the world, forcing us to confront the past, present, and future. They also offer us a chance to assess and question the current practices and priorities of both grassroots communities and institutional organizations, particularly those within collaborative arrangements. For instance, we can better understand how such actors ensure local inclusion and manage decisions in the context of rapid technological innovation and their broader social structures (Smith et al., 2014). Furthermore, participatory designers must expand their focus beyond merely identifying power imbalances, engaging in critical investigations into other aspects of organizations, such as their ability to create meaningful participatory institutions that genuinely foster empowerment, the potential need for institutional adjustments, or the creation of new frameworks (Kaufman, 1997).

In addition to insights derived from specific cases, PD attempts to develop new approaches have also proved valuable. For example, Broadley & Dixon (2022) explore how participation requests (PR) allow organized communities to initiate an “outcome improvement process” dialogue with public authorities to address pre-identified local issues. Since such an approach risks excluding informally organized groups, Broadley and Dixon (2022) and McKercher (2020) highlight the importance of integrating the power-sharing principles of PD with capacity-building efforts to ensure more diverse participation. To facilitate such capacity building, participatory designers must encourage collective learning between community practitioners and public governments (van der Bijl-Brouwer, 2019). When participatory designers expand their focus beyond crafting participatory methods to include capacity building with grassroots actors, they can increase community engagement, strengthening the community’s role in influencing policy agenda-setting. PD also has the opportunity to raise community awareness about the potential challenges and complexities inherent in collaborations with government institutions, whose decisions are more often guided by policy targets and funding allocation (Vaz et al., 2022). Conversely, encouraging representatives within public government to engage with grassroots organizational methods is equally critical (Bason, 2016).

This concept of collective learning across diverse domains and the commitment to democratic ideals have both been central to the field of PD since the 1970s (Robertson & Simonsen, 2012), while Bødker et al. (2022) have identified other foundational elements of PD: fostering democracy in the workplace and beyond, empowering individuals through the design process, promoting emancipatory practices rooted in mutual learning, and recognizing human beings as skillful and resourceful in the development of future practices. Moreover, the politics inherent in design processes, as well as the responsibility to politicize design by engaging both local and global actors, are central aspects that define PD (Bødker et al., 2022).

To effectively assume political responsibility, Bason (2016) argues—through his articulation of the emerging field of policy design—that design and policy must become more closely integrated. To this end, rather than simply adding to the current set of policy tools, he emphasizes exploring the role of design to transform policymaking practices. The concept of institutioning, situated at the intersection of public institutions and communities, provides direction for PD to achieve such an integration. Specifically, institutioning refers to the relationships that participatory designers initiate with institutions as well as the connections they facilitate both between institutional entities and between institutions and communities, where complex relationships and interactions among these actors are directly impacted by PD processes.

Institutioning involves a practice of interweaving between—as well as producing—various insides and outsides in participatory processes, by consolidating and challenging existing institutional frames as well as by forming new ones. Institutioning stresses the promise of PD and Co-Design processes being substantial political practices in which researchers, designers and other actors can play a role in shaping not only our shared public spaces but our shared public institutions. Institutioning could contribute to a heightened understanding of the way PD and Co-Design processes continue to coevolve with historical, geographical and institutional factors. (Huybrechts, Benesch, et al., 2017, p. 158)

The question comes down to how participatory designers can effectively carry out institutioning work; that is, how they can position themselves within the policymaking process to enhance communication between public institutions and communities to achieve more favorable outcomes. They must develop capabilities that allow them to mediate in bottom-up policy change movements, navigate complex political contexts, and ensure that collective action, grassroots initiatives, and social movements adequately address public concerns while engaging with responsible institutions. At the same time, however, participatory designers need to engage with top-down policy-making approaches (Vaz et al., 2022). This complex “in-between” position illustrates how participatory designers operate at the meso-level, bridging the gap between institutions and society (Disalvo, 2022; Vaz et al., 2022). Further complicating matters, institutioning processes can take multiple forms: conducting design interventions within policymaking processes and communities to enhance collaboration; identifying and shaping spaces and places (physical and organizational) for capacity building among both designers and policy-makers to enhance dialogue and trust; and exploring design frameworks and methods that can drive innovative policymaking (Mortati et al., 2022).

Institutioning: Key Challenges

As previously discussed, significant challenges confront participatory designers attempting to mediate the labor of institutioning processes between grassroots communities and public governments for the purpose of integrating them into the latter’s work practices. First, while PD has the potential to shape institutioning processes, participatory designers should be careful not to oversimplify matters by making general claims about the effectiveness of design methods in addressing complex policy issues without adequately adapting their designs to the realities of public administration. Designers often lack the capabilities and experience necessary to navigate the scale, interdependence of public problems, and power dynamics within and around public sector institutions. These institutions are complex environments involving multiple stakeholders, diverse interests, and the potential for various conflicts (Bason, 2016; Mortati et al., 2022). Designers in such environments may struggle to identify the proper timing of an intervention or to clearly define their role. Second, the impact of PD activities on governmental practices as well as on political and democratic life has not yet been sufficiently investigated. Third, documented cases within the current literature are limited in terms of their geographic diversity, scale, breadth, and depth. Finally, the intermediary position of participatory designers demands constant negotiation—not only with people—but also with more-than-human actors, encompassing nature and other natural and technological systems. This necessitates design tools that can facilitate mediation as well as the ability to collect and store the vast amount of information associated with these entities (Marres, 2023; Mortati et al., 2022). As Marres (2023) states: “We will need to engage much more deeply with feminist understandings of politics, which affirm materiality, embodiment, and connectedness as unavoidable political realities” (p. 973). This perspective is particularly relevant to our documented cases, which deal with the materialities of houses, roads, and open spaces.

Addressing These Challenges

To identify solutions to the challenges discussed above, we first conducted a review of the current literature. We primarily searched for sources from design, social science, and policy-related journals and conference proceedings using keywords such as “Participatory Design,” “Policy Design,” “Grassroots Communities,” and “Institutioning.” From the 33 literature sources we selected as most relevant, we performed an analysis based on models of descriptive data extraction and synthesis (Heyvaert et al., 2016) to identify actions that enhanced collective learning between policymakers, communities, and material actors. Descriptive data was extracted from all sources, a process that was iterated when new insights emerged, with ongoing collaborative discussion among all authors throughout. The actions identified through this analysis require further research to fully understand their advantages, disadvantages, timing, and role in crafting strategies for lasting organizational change (Brinkman et al., 2023). The literature review also demonstrated how PD can impact institutioning processes, shaping actions between the labor of grassroots initiatives and governments; specifically, how informed interventions in grassroots labor can direct and enhance governmental work.

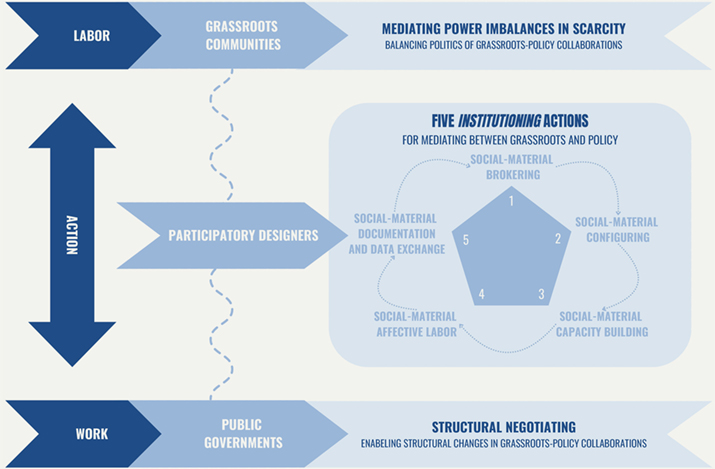

To better visualize the challenges facing institutioning processes, we outlined a series of institutioning actions that support collective learning through capacity building within policymaking processes (Figure 1). These actions encourage participatory engagement with grassroots communities (Bason, 2016), thereby increasing community involvement in policymaking decisions (Vaz et al., 2022). It builds on insights drawn from the literature review, with particular inspiration from recent research by Hernberg and Hyysalo (2024).

Figure 1. Unfolding institutioning. (Based on Arendt, 2013; Brinkman et al., 2023; Disalvo, 2022; Hernberg & Hyysalo, 2024; Huybrechts et al., 2017, 2018; Mortati et al., 2022; Sabie et al., 2022; Smedberg, 2022)

Based on Arendt’s (2013) terminology, the double arrow titled “Action” represents the tension within current institutioning processes between the realms of labor and work. The former is linked to grassroots initiatives, which can mediate power imbalances in contexts of scarcity through community participation and the collection of feedback about the needs of community members. In contrast, the more traditional work sphere, which is linked to public governments, requires structural negotiating (Hernberg & Hyysalo, 2024). This sphere relates to regulations and policymaking, opening up opportunities for new ways of social and technical organizing. However, effectiveness in this realm necessitates building greater confidence in design-based thinking within policy contexts by demonstrating its potential as well as providing guidance and training (Brinkman et al., 2023). Although participatory designers’ institutioning work in grassroots communities often occurs within the relatively smaller context of labor (i.e., among those directly and indirectly involved), negotiating to transform work practices requires engagement on a broader governmental scale, requiring changes in how participatory designers situate and perceive such work (Brinkman et al., 2023; Disalvo, 2022).

Therefore, the double arrow allows us to identify the nature of institutioning processes as it moves between the two levels, operating between distinct actors and spheres to reduce tensions and potential conflicts between them. This arrow also represents the role commonly performed by participatory designers, articulated in the literature through five key actions. By categorizing and defining these actions, institutioning processes become more structured and easier to comprehend and analyze. To conceptualize these actions, we build on insights from Hernberg and Hyysalo (2024) and Mortati et al. (2022), but we deliberately add the prefix “socio-material” to the actions that negotiate between labor and work. This addition highlights how such actions expand, define, and complicate the intermediary role of participatory designers, who must negotiate not only between human actors (the social component) but also mediate between more-than-human actors (the material component, which can include resources such as stones, work materials, natural elements, etc.) that play a role in sustainable transition processes in contexts of scarcity (Marres, 2023).

Action 1: Socio-material brokering. During our analysis, the need for participatory designers to establish feasible channels for participation via design approaches became increasingly clear. Such an approach should differentiate between various kinds of interactions among public governments, communities, and material actors as they relate to labor; for instance, by self-organizing the design of roads through the creation of shared and safe public work environments. Hernberg and Hyysalo (2024) describe this process of building connections among different actors and resources (which may include the introduction of new actors) in sustainability initiatives as “brokering,” which requires constant analysis, synthesis, and evaluation (Mortati et al., 2022). In this scenario, participatory designers do not assume a leadership role but rather collaborate with collectives to conduct experiments that engage communities, institutions, and more-than-human actors, facilitating meaningful exchanges (Disalvo, 2022). Such experiments, occurring in real time, must avoid treating the actors involved as monolithic entities and instead consider the subtle differences and subjective viewpoints of each participant involved. Each encounter is uniquely configured, and any time an outcome is reached, the steps that led to it should be documented for future reference. Although these experiments take place on a small scale, or as Disalvo refers to them, “in the small” (2022), they demonstrate the potential for design-based alliances both internally (building relationships, creating a group identity, promoting engagement) and externally (expanding beyond known boundaries by seeking alignment, e.g., via civil servants with strong networks, by bypassing existing structures, etc.) (Brinkman et al., 2023).

Action 2: Socio-material configuring. The literature also reveals potential for design techniques (e.g. prototyping) to enhance the materialization of policies and public decisions, which can reshape democratic discussions (Mortati et al., 2022). Configuring involves altering technologies, materials, or social configurations, contributing to the practical implementation of innovative and intermediating design practices (Hernberg & Hyysalo, 2024). Institutioning practices in design tend to approach situations through making, which refers to promoting engagement between policymakers and community members. However, “making” must be critically examined before alternative pathways for policy and civic action can be fully realized, leading to a shift from alternative labor practices to innovative policy work practices (Disalvo, 2022).

Action 3: Socio-material capacity building. Current research indicates that new capabilities for both the public sector and communities need to be explored to handle the complexity and uncertainty of contemporary public challenges related to labor. By applying principles and approaches from PD, such capabilities can be integrated into new work practices (Mortati et al., 2022). Here, the participatory designer role consists of facilitating and building the capacity to enable experimentation, encourage learning, and support the expression of diverse views and concerns (Hernberg & Hyysalo, 2024).

Action 4: Socio-material affective labor. The literature also highlights aspects of care involving more-than-human actors. Affective labor describes how the emotional component of an experience changes and accumulates during a co-creative process, affecting both human and more-than-human actors, revealing an aspect of unseen, emotional labor essential for sustaining collaborative efforts (Smedberg, 2022). On one hand, affective labor helps to explain why grassroots initiatives are undertaken and why grassroots communities, public governments, and participatory designers become engaged in institutioning processes that often lie beyond their work spheres. On the other hand, it introduces new complexities into processes involving more-than-human actors (e.g., emotional attachments and connectedness to houses, parking spaces, etc.).

Action 5: Socio-material documentation and data exchange. Participatory designers hoping to support grassroots labor to transform governmental work practices need to advance research in the areas of documentation and data exchange. Such research can inform the preparation and implementation of institutional policies while guiding the development of design techniques, creating a vast well of data that can be used by future researchers and designers. To support PD processes, it is essential that such data demonstrate progress, enhance visibility, and foster empathy (Brinkman et al., 2023), rather than merely supporting evidence-based models and big data analysis (Mortati et al., 2022). Agonistic data practices, which emphasize contestation and alternative perspectives, can promote new political arrangements and contribute to long-term collective action in more meaningful ways (Disalvo, 2022; Sabie et al., 2022).

Methodology: A Comparative Analysis of Two Case Studies

To answer the study’s research question, “How can we better articulate and develop institutioning actions that tap into grassroots labor by communities to innovate the work practices of public governments dealing with sustainable transitions in contexts of scarcity?”, this article conducts a comparative analysis of two case studies (Yazan, 2015; Yin, 2009).

A case study can be defined as a contemporary phenomenon examined within its real-world context. Often, the boundaries between a phenomenon and its context are not strictly defined, and researchers may have little control over either (Yin, 2009). Nonetheless, the study of real-world cases often provides a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena than controlled experiments and has the potential to bring us closer to answering the research question than experimental methods alone. For this paper, we apply a multiple embedded case study approach, which breaks down each case into subunits for more detailed analysis. Since each case occurs in a unique context involving distinct processes, the separation of various elements enables more nuanced comparison and analysis. Therefore, this research design offers the most promising approach to answering our research question.

We hypothesize that applying the model we developed based on our literature review (Figure 1) as an analytical lens will provide a deeper understanding of the challenges inherent in institutioning processes as well as strategies for addressing them. This model is used to analyze two cases presented below.

Two Cases Involving Labor, Work, And Action

The first case is set in Tanzania, where the third author of the article has been involved in public services since 2013. In his role as town planner at the Regional Administrative Secretariat and District Council, the author addressed issues surrounding land conflicts that often arise during sustainable transition processes and rapid urbanization (UN Habitat, 2020). This experience inspired him to redirect his efforts toward a PhD in PD, focusing on the labor of grassroots communities. Adopting a participatory approach, he paid particular attention to the action sphere, supporting both the government and local communities during a realignment of their roles to resolve land use conflicts in which private and public interests were at odds. This particular case deals with budget constraints that initially prevented road upgrades in the Mbezi Luis sub-ward of Ubungo Municipal Council.

The second case study is set in Belgium. The first, second, and fourth authors of this article, all of whom have academic backgrounds in PD, political science, and sustainable design, present this case to demonstrate how a public government, a local community, and a group of designers can collaborate and use negotiation to change the intended use of an old pastoral house in Houthalen-Helchteren, Belgium. Initially put up for sale by the government, the building was later repurposed as a community infrastructure in response to a lack of public resources in the area.

The institutioning process serves as a common thread running through both cases, which describe the integration of various internal and external factors through the participatory process, during which improved practices are consolidated and existing institutional frameworks are challenged or replaced by new ones (Huybrechts et al., 2018). This article also explores various challenges faced by participatory designers around the world as they carry out institutioning actions, navigating between communities’ grassroots initiatives and public organizations’ sustainable transition processes.

Returning to our research question, our comparative analysis draws insights from two case studies conducted in different parts of the world to provide in-depth information about institutioning processes. Table 1 outlines how data and evidence were collected. The subsequent data analysis will focus on labor (i.e., grassroots labor), work (public governmental work), and action (the intermediary role of the designer), as well as related challenges viewed through the lens of our model (Figure 1).

Table 1. Overview of the case studies’ evidentiary sources (based on Yin, 2009).

| Evidentiary sources based on Yin (2002) |

Case 1: Upgrading a road in Mbezi Luis sub-ward, Ubungo Municipal Council, Tanzania | Case 2: Urban harvesting in Houthalen-Helchteren, Belgium |

| Documentation | Literature review on institutioning and the roles government institutions are mandated to perform in the provision and maintenance of infrastructure services | Literature review on institutioning and the roles government institutions are mandated to perform in the provision and maintenance of infrastructure services |

| Governmental documentation | Student and governmental documentation of materials and methods for urban harvesting | |

| Archival records | Approved settlement regularization scheme | Archival material on the building, masterplans, and roads |

| In-depth interviews | Grassroots leaders (ward executive officers, MTAA executive officers) who work in neighborhoods as intermediaries between communities and municipalities | Neighborhood group leaders |

| Professionals from municipal offices in the Mbezi Luis sub-ward of Ubungo Municipal Council | Professionals from the municipal office in Houthalen-Helchteren | |

| Professionals from the national level of the Dar es Salaam Land Commissioner Office, focusing on land use conflict resolution and community involvement in decision-making processes | Professionals from the local level of the Flemish Commissioner Office, focusing on land use conflict resolution and community involvement in decision-making processes | |

| Direct observations | How designers, communities, and public administrators manage their daily activities (e.g., participation in meetings to gain insight into the decision-making processes of the community and public administration) | How designers, communities, and public administrators manage their daily activities (e.g. participation in meetings to gain insight into the decision-making processes of the community and public administration) |

| Participant observations | Management of the process | Involvement in an urban harvesting and circular building festival |

| Physical artefacts | Upgraded road | Community infrastructure/space |

Contextualization of the Cases

Table 2. Overview of the case studies’ contextualization.

| Contextualization | Case 1: Upgrading a road in Mbezi Luis sub-ward, Ubungo Municipal Council, Tanzania | Case 2: Urban harvesting in Houthalen-Helchteren, Belgium |

| Size of the neighborhood | 73,000 inhabitants | 30,869 inhabitants |

| Type of urban governments/relevant agencies | Tanzania Rural and Urban Road Agency (TARURA), municipality | Municipal, regional |

| Type of grassroots community involved | Neighbors near the road organized by the elected volunteering committee, ten cell leaders, and MTAA leaders | Local neighborhood initiative mixed with recreative associations |

| Timeframe of the case | February 2023 - present (ongoing) | 2022 - present (ongoing) |

| Key actors | Neighbors near the road, elected volunteering committee, ten cell leaders, MTAA leaders, ward executive officer, municipal experts (town planners, land surveyors, engineers), Tanzania Rural and Urban Road Agency (engineers), and district commissioner | Houthalen-Helchteren municipality (Spatial Planning and Social Department), adult education, 2 architectural offices, Flemish government, 4 urban design offices, Studio NZL |

| Role of Participatory Designer | Observing the initiative on-site by working with MTAA leaders at the MTAA office and interviewing all the key actors in the process with a focus on community-based PD strategies to minimize land conflicts within informal settlements | Working from within the University, with activities ranging from research, translation, mediation, and co-coordination of urban harvesting processes while offering expertise in sustainability and PD |

Case 1: Upgrading a Road in Tanzania

The administrative sub-ward of Mbezi Luis is one of the fastest growing areas within the Ubungo Municipal Council. Situated near a recently upgraded six-lane trunk road, the area benefits from its proximity to an intercity bus stop, a park, and a regional bus terminal capable of accommodating 700 buses and 80 cars, with approximately 3,000 daily departures. These recently built strategic government projects have significantly increased land values and accelerated the rate of urban and spatial development in and around the ward (Magina et al., 2024). With a population exceeding 73,000 inhabitants, Mbezi Luis’s rapid development has occurred somewhat informally, a result of the municipality’s limited resources that prevented it from preparing detailed city development plans or enacting appropriate development control measures. Ongoing land development and subdivision activities have pushed the existing infrastructure—in particular, the area’s roads—to the limit, creating a critical need for innovative solutions and improvements.

The three-kilometer stretch of road under discussion in this case connects two neighborhoods and was previously a footpath without specified standards or a designated width. As spatial development progressed in the area, the road became narrower due to new encroaching structures, with some sections reaching a maximum width of just four meters. Over time, more buildings were constructed, many of which came to be used as residential spaces that featured retail shops, increasing foot traffic and far exceeding the road’s capacity.

In 2017, efforts to regularize the unplanned area commenced, including plans to widen the road to twelve meters. Since the road connects two wards, responsibility for its routine maintenance was allocated to the Tanzania Rural and Urban Road Agency (TARURA) to ensure compliance with existing regulations. However, TARURA determined that the width of the road should, in fact, be fifteen meters, contradicting the previously approved regularization plan. Meanwhile, the road continued to deteriorate due to the increased number of users, the high rate of urban sprawl, and ongoing spatial and building development. During the rainy season, the road became completely impassable, forcing users to divert vehicles to adjacent undeveloped plots of land or walk.

Case 2: Urban Harvesting In Belgium

The North-South Limburg (N74/N715) is a road that sees heavy traffic as it connects the Belgian and Dutch cities of Hasselt and Eindhoven. As it passes through the center of the municipality of Houthalen-Helchteren (BE), it impacts the road safety, mobility, and quality of life of the region’s residents. As a result, the Flemish government initiated the “Complex Project North-South Limburg” to enhance livability in the region through sustainable mobility and environmental improvements. To manage the project, Studio NZL, an interdisciplinary consortium including research, design, communication, and management experts, was established. To create the additional space required to carry out the project, the Flemish government purchased buildings, houses, and plots of land, directly impacting residents in the municipality, some of whom lost homes or parts of their land or faced other disruptions and inconveniences during the construction process. For these reasons, communication about project processes and objectives as well as its execution required careful supervision and handling to address concerns within the community. The current phase of the project, running from 2022 to 2024, is focused on delineating acquisitions.

Moreover, it was crucial for the expropriation process to align with the project’s core value of sustainability. The planned demolition held significant potential for urban harvesting and the revaluation of materials that would otherwise become waste. This potential was underpinned by three key considerations: (1) ecological benefits, (2) symbolic and sentimental value, and (3) the rising costs of construction materials. These factors prompted critical questions about how to best enhance the livability of the municipality and meaningfully repurpose harvested materials. Given the sensitivity of using people’s personal property in a circular process, it was essential to first establish appropriate procedures that would ensure a meaningful and beneficial outcome. To this end, it was decided that all harvested materials would be used for a community project: the renovation and extension of a pastoral house called Living Lab, a long-term initiative fostering socio-material exchanges between human and material actors (Björgvinsson et al., 2010).

Innovative Approaches for Sustainable Transitions

Case 1: Upgrading a Road in Tanzania

Of their own accord, affected residents and other road users initiated road improvement discussions through WhatsApp groups, with the ultimate goal of ensuring that the road could be used during all times of year in any weather conditions, and that it would be wide enough to accommodate two-way traffic simultaneously. Some residents volunteered to find technicians to assess the road and provide budget estimates for the proposed improvements. This information was then shared within the community group to coordinate the collection of funds and materials. Since the road fell under the jurisdiction of the government’s urban and rural road agency (TARURA), community members reported their plans to the agency, seeking official recognition and approval by the government and greater community. Sub-ward leaders advised them to propose volunteer leaders to oversee fund collection and allocation during the project’s implementation, and at a later community meeting, the approval of these leaders was confirmed. Following their confirmation, these leaders cooperated with sub-ward officials to present the plan to the district commissioner’s office and the municipality for approval and additional support.

Sub-ward leaders continued to cooperate with community leaders and municipal experts to improve the plan to transform deteriorated sections of the road to achieve all-weather capabilities, with much of the work to be undertaken by community members. The district commissioner, along with sub-ward leaders, was invited to mobilize community involvement in the road improvement initiative. After assessing the condition of the road, the commissioner attended a public meeting to formally endorse the initiative and encourage participation from the community and other stakeholders.

Following inspections by road improvement experts, it was determined that some sections of road could not be expanded beyond a width of ten meters without encroaching on adjacent structures. In heavily built-up areas, however, the maximum width was a mere four meters, and expanding these sections required negotiations with nearby landowners. Since the landowners were asked to accept the expansion of the road without being compensated for potential loss of property, sub-ward officials and community leaders worked together to reach agreements with them. The negotiations were eventually successful, with landowners accepting the expansion plans after town planners and land surveyors placed survey pegs to demarcate the boundaries of the proposed road. TARURA also supported the project by donating construction materials (14 lorries of rubble), and the municipal director provided an excavator for four days. Meanwhile, project leaders collected over 11 million Tanzanian shillings (approximately $4,231) from community members and volunteering stakeholders to help fund the project.

Case 2: Urban Harvesting in Belgium

Urban harvesting has received increased attention, primarily in the context of large-scale buildings such as offices and schools. However, its application in small-scale, community-driven grassroots initiatives presents unique challenges, especially in the context of housing impacted by expropriation. Affected community members typically want to know whether (and which) materials from their homes will be reused in community projects, while others, dealing with the emotional impact of expropriation, prefer not to confront such details. To address these varying needs, urban harvesters in this case study documented all materials in a traceable manner, ensuring that former residents could access this information later if desired. Additionally, their neighbors were contacted regarding the harvesting activities, as people living nearby were inevitably curious about the process and often had personal connections with buildings or previous owners. Understandably, the experience of urban harvesters working in anonymous office buildings differs substantially from those handling expropriated homes, where personal remnants of people’s lives remain behind.

It should be noted that the harvesting of materials was not initially planned but gradually emerged after several houses and buildings had already been expropriated, and preparations for demolition were underway. At that time, students from UHasselt began to conduct an exploratory study to assess the potential of urban harvesting. Over the course of a six-month live project, they adopted a festival format to organize workshops, lectures, and urban harvesting walks, engaging with the neighborhood, municipality, architects involved in renovating the old pastoral house, and building professionals. By involving the municipality, a local school, and the neighborhood in their small-scale prototyping experiments, the students inspired the actors involved in the Complex Project North South Limburg. Interest in urban harvesting grew, and architects, residents, researchers, students, and municipal representatives self-organized to voluntarily harvest materials for the old pastoral house renovation, while a network of local actors was also established to support the urban harvesting process. This network included the center for adult education, which began exploring ways to upscale the harvesting process, such as by reclaiming larger quantities of materials and materials requiring greater technical expertise, activities that were later added to their training program. The technical school and local building professionals were also consulted for technical advice.

Figure 2. Building festival and materials in Houthalen-Helchteren.

(Source: fieldwork in April 2024; images by Olmo Peeters)

Challenges during the Institutioning Processes

Case 1: Upgrading a Road in Tanzania

Since the collected funds did not meet the proposed goal, volunteer leaders and residents contributed labor to the work of the municipality and TARURA engineers to optimize available resources. The plan was revised to accommodate a seven-meter-wide road and negotiated with local residents (Figure 3). During implementation, volunteer leaders were responsible for supervising on-site activities, managing the supply of materials, and providing feedback to the community, which was primarily achieved through the WhatsApp group. Municipal and TARURA experts inspected the work and provided guidance to the volunteer committee regarding specific tasks and standards. Overseeing the distribution of labor proved challenging and highlighted a need for more effective and transparent documentation to ensure that all stakeholders could monitor the project’s progress.

Figure 3. Improved sections along Mbezi Luis-Kwa Robert Road. (Source: fieldwork in July 2023; images by Gasper Kabendela)

Case 2: Urban Harvesting in Belgium

The involvement of numerous actors and the limited time available for harvesting necessitated the establishment of a single contact point within each organization who could be available to promptly address questions. There was also a need for prior agreements that could clearly define the conditions and purposes of the material harvesting. For instance, harvested materials could only be used for the renovation of the old pastoral house and could not be sold for personal profit. From a legal perspective, various issues arose regarding the ownership of harvested materials and the associated dismantling costs (e.g., electricity, saw blades, grinding wheels, insurance for volunteers, transportation). When harvesting began, the tender procedure for the renovation had not yet been settled, so harvested materials had to be excluded from this process. As the “client” of the old pastoral house project, the municipality was charged with finding a way to cover the harvesting costs prior to the project’s execution phase.

Prior to harvesting, the planning phase was essential to ensure that buildings were accessible, electricity and water were available, and participant details were documented for insurance purposes. Given the several months’ interval between the material harvesting and the renovation of the old pastoral house, it was necessary to make arrangements for the temporary storage and later transportation of the materials. Potential storage locations were screened in collaboration with the municipality. Apart from logistical considerations, storage and transportation also required clear agreements between various actors to define their responsibilities. Furthermore, the involvement of non-construction professionals in the harvesting activities inevitably led to technical questions, ranging from guidance on dismantling procedures and the appropriate use of tools to feedback on cleaning reclaimed materials to meet contractors’ usability standards. Designers in this case played a pivotal role in mediating between the labor of communities and students and the work of the municipality and subcontracted architectural office.

Findings: Institutioning in the Case Studies

The literature review explored the intermediary role of participatory designers in institutioning actions to bridge the gap between grassroots communities and public governments when addressing sustainable transitions, particularly when governments lack sufficient means and innovative approaches. In the two case studies presented here, we discussed grassroots initiatives aimed at reappropriating property in socially and materially sustainable ways: reclaiming a road and creating a communal space in contexts of limited public resources.

Although such self-organized initiatives tend to be more common in Tanzania than in Belgium, they represent a growing practice globally, driven by the challenges presented by achieving sustainable transitions. Our observations reveal that not only grassroots communities but also public governments and participatory designers are capable of engaging in labor practices beyond their professional contexts and conventional approaches to work. Such efforts are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and sometimes uncertain, motivating the search for effective labor approaches that can result in more organized work practices. It is neither possible nor desirable to formalize every aspect of these processes into structured work forms, as alternative methods will always naturally emerge through dialogue between grassroots communities and institutions. However, to prevent participants from lacking motivation due excessive uncertainty regarding project details, we specifically analyzed cases to develop institutioning strategies to make labor more manageable (Figure 1).

Mediating Power Imbalances in Contexts of Scarcity

While specific policy designs vary by case, most examples adopt top-down approaches that lead to implementation challenges, as the primary responsibilities usually fall on a limited group of stakeholders. In the cases discussed above, policies were partially designed at the ministerial level, with academic consultancy agencies occasionally contracted to develop and execute specific activities. Local government authorities also provided their expertise in managing public spaces on the local level. However, authorities are often uncertain about how to incorporate the expertise of grassroots community members into design processes (Morshedzadeh et al., 2022).

Both cases originated from tensions driven by scarcity that required institutional support; since the relevant public governments lacked the immediate means to provide assistance, the community took the initiative by advocating for an accessible road or community space, respectively, in a context where municipal funds were insufficient. The grassroots communities’ reappropriation of territories was motivated by a desire to improve the well-being of local community members; however, they encountered various challenges, including bureaucratic barriers (e.g., municipal council requirements) and power imbalances, as well as the influence of market developers who undermined the municipal authorities’ confidence in the proposed interventions. For example, the municipality was reluctant to remove the “For Sale” sign from the pastoral house after they had put it on the market because they lacked the means to redevelop the property themselves. In another instance, they were unwilling to widen sections of road near the homes of powerful people.

This is where participatory designers played a crucial role, analyzing and mediating between actors separated by power imbalances, all while addressing the scarcity of resources (Jagtap, 2022). In the first case, community members started by organizing themselves into a community group. Since the road upgrades required adherence to official standards and procedures, the participatory designer engaged with MTAA leaders on a local level (i.e., mediating between grassroots and government entities). This resulted in MTAA leaders becoming actively involved in co-organizing initiatives, facilitating public community meetings, selecting a temporary committee for oversight, and providing feedback. This collaboration enabled the committee to connect with other non-governmental institutions and obtain expert and material support in the process. WhatsApp groups served as a key communication medium during the planning, execution, and fundraising phases and also made it possible to easily share updates and promote daily engagement.

Action 1: Socio-material Brokering

The community members in Mbezi Luis subward, brought together by shared concerns, relied on self-organized community actions to overcome a lack of open space (scarcity) that affected their daily mobility to reclaim and upgrade a quickly deteriorating road. Decisions were made materially and collectively, ensuring that the voices of diverse community members were represented and heard (Hou & Rios, 2003). Although socio-material brokering practices are discussed extensively in PD and institutioning literature, discussions on materiality are often limited to mediating information technologies, with recent research just beginning to explicitly address more-than-human actors (e.g., nature, stones) (Giaccardi et al., 2024).

The cases explored in this paper involve a diverse array of material actors, including the materials for sustainable redesign that are harvested from unused infrastructures, using appropriate tools. Moreover, it is crucial that harvesting activities are carried out while engaging responsibly with the surrounding natural environment. The participatory designers acted as mediators in ongoing brokering processes, which were often unfamiliar due to technical and regulatory challenges. In addition to the affective and social dimensions, the material labor also required extensive effort, involving actions such as negotiating access to electricity in abandoned buildings to retrieve materials in Houthalen-Helchteren. This socio-material brokering involved significant micro-work and a lack of precedents to guide them. The participatory designers faced new questions, such as: How can an urban harvesting process be successfully organized when the availability of materials, the support of partners, and the application of rules are all uncertain? Meanwhile, participants in this case had to reimagine their relationships as they adapted to changing socio-material conditions on-site, leading to several unexpected scenarios (Have we raised enough money? What material resources and human actors are available in the community?). These processes were not always cheaper or easier to execute and thus diverge from neoliberal strategies that delegate labor activities to communities (Kaethler et al., 2017). Ultimately, the actors involved were united by a shared ambition to live and work in more inclusive and sustainable ways.

Action 2: Socio-material Configuring

Substantial effort was required to reimagine and configure grassroots-policy socio-material relations within design artefacts. The cases contributed to more distributed road and building designs, respectively, that were not based on traditional design processes, but rather utilized reused or surplus materials. Participatory designers must either continuously reinvent the configuration of these processes or establish a more effective information infrastructure to allow for the documentation and sharing of example methods, tools, and artefacts that both governments and communities can apply. Such efforts can support the identification of available resources, bring people and materials together, aid in the design of artefacts, and sustain ongoing collaboration. At present, WhatsApp and email provide ideal infrastructures for collaboration and communication, but they do not support the necessary documentation practices.

Action 3: Socio-material Capacity Building

Another key challenge facing PD practitioners is the preconceptions that communities, designers, and policymakers hold about each other. For instance, policymakers often assume community members are not interested in sustainability issues, because their concerns are usually expressed using non-professional language. However, in the Belgian case, residents’ efforts to realize a community space were clearly rooted in a common desire to ensure a sustainable transition, indicating a commitment to sustainability. The challenge lies in moving beyond these preconceptions through collaboratively building socio-material capabilities in the field.

On one hand, the grassroots communities required support to develop capabilities in several areas: facilitating interactions with various governmental contacts, navigating rules and regulations (e.g., what could be built, limitations, and necessary permissions), accessing materials and technical tools (sourcing and transportation), and engaging with design processes (designing road and building modifications). Conversely, the governmental institutions involved needed to build the capacity to work with large groups of volunteers whose actions and communications required extensive oversight. This was easier to achieve in Dar es Salaam, where an intermediary assisted with policy on the local level, facilitating cooperation between the communities and policymakers and enabling the acquisition of social and material infrastructure to support institutioning activities. Regardless of the presence of such intermediaries, the participatory designers often stepped into this role, embedding themselves deeply in two worlds to understand both communities’ and institutions’ capabilities and to offer help with any challenges that might arise. In both cases, participatory designers brought years of experience in institutional settings, allowing them to incorporate policy expertise in addition to their design skills.

Action 4: Socio-material Affective Labor

The traditional view that only governments should be responsible for infrastructure is based on the notion that residents prioritize their own interests over the sustainability of the collective environment, which is challenged by the case studies described in this paper. In our examples, the communities increasingly assumed ownership of these sites, displaying a strong desire to improve their environment. Community involvement in sustainability initiatives took on multiple forms that were shaped by distinct local contexts and needs.

In both cases, the participatory designers observed that when working in contexts of scarcity, it was crucial to pay attention to public attitudes toward grassroots practices and investigate people’s motivations for engaging in laborious design processes. Municipalities were motivated by goals such as supporting social cohesion (via the development of community infrastructure) and conflict prevention, while communities sought tangible neighborhood improvements. Participatory designers, meanwhile, were driven by the opportunity to explore innovative design processes. Notably, saving time or money was not cited as a primary motivation by any of the actors involved. These dynamics suggest that participatory designers need to cultivate a sensitivity to socio-material affective labor. In the context of the Belgian case, this means they need to address emotional attachments to expropriated and demolished houses and acknowledge the often unseen emotional labor involved in sustaining collaborative processes (Smedberg, 2022).

Action 5: Socio-material Documentation and Data Exchange

The participatory designers identified a critical need for socio-material documentation and data exchange to support the emerging practices of brokering, configuring, capacity building, and affective labor between human and more-than-human actors. Improved documentation methods could make such practices less labor intensive than they are today while offering guidance to public governments seeking to undertake new projects. Documentation became particularly important during and after the design process, when participatory designers brought together many different actors (residents, administrative departments/levels, mediating organizations) over the course of numerous meetings. The complexity of such activities made it difficult to maintain a comprehensive overview of the attendees, interactions, and details of the artefacts gathered and created. Access to such documentation from previous projects would have also served as an invaluable reference point during the planning stages.

Structural Negotiating

The participatory designers faced significant challenges while attempting to understand how design tasks are commissioned by public governments. Sustainable upgrade methods, along with the reuse, cleaning, and storing of materials typically increased costs and construction timelines, making it even more difficult to integrate these innovative labor approaches into the government’s work practices.

The cases revealed additional uncertainties regarding roles and responsibilities. Even determining who was the actual commissioning authority was not always clear: was it the national government, the local government, the universities whose PD researchers were experimenting with new collaborative approaches, or the communities? This lack of clarity regarding project ownership raised further questions: Who is liable in the event of an accident? Who’s responsible for paying electricity fees? Who has control of the harvested materials? And so on. Regulatory frameworks to guide such processes were notably absent, further complicating these efforts. Ethical considerations were similarly vague. Who ensures ethical conduct during data collection? Who is responsible for obtaining the informed consent of the various actors involved? Despite these uncertainties, social-material brokering, reconfiguring, affective labor, and capacity building helped to cultivate trust among all actors involved, highlighting the benefits of overcoming risks through collaborative actions.

Conclusion: Institutioning as Action

This article contributes to the ongoing discourse regarding the impact of PD on institutioning processes by examining the complex yet potentially productive relationships between grassroots communities and public institutions. Specifically, our research focused on participatory designers’ institutioning actions to enhance the labor of grassroots communities, thereby inspiring innovative work practices within public governments—particularly those attempting to realize sustainable transitions in contexts where resources are limited. To this end, we structured institutioning processes along two primary dimensions within collective learning (Bason, 2016); one from the perspective of grassroots communities (labor) and another from the perspective of public governments (work). Furthermore, we determined that these processes are mediated by five key actions (Figure 1), all of which are socio-material in nature and encompass both human and more-than-human actors. We deliberately added the prefix “socio-material” to each action to emphasize how they negotiate between labor and work practices as they expand, define, and complicate the intermediary role of participatory designers.

Connecting Grassroots Communities and Institutions

Participatory engagements with grassroots communities’ labor are often characterized by the involvement of community members, public officials, and designers operating outside of their usual work contexts and approaches. To facilitate a partial integration of this labor into the work practices of public governments, participatory designers undertake various institutioning actions, which are detailed below.

Action 1: Socio-material Brokering

Brokering between actors involves the creation of socio-material relationships that often entail several material actors, extending beyond traditional informational structures (Disalvo, 2022) to include material elements from the surrounding environment. In common design settings, these materials come from certified producers, while here they are part of the environment and are brought together organically, much as PD tends to do with human actors.

Action 2: Socio-material Configuring

Configurations of socio-material relations in artefacts occur in unexpected places, taking the form of roads, buildings, and open spaces, making them difficult to replicate in other settings and creating barriers to collective learning at the artefact design level. However, it is possible to document, share, and repeat the methods participatory designers use to facilitate grassroots-policy collaborations between human and more-than-human actors and apply them in other contexts.

Action 3: Socio-material Capacity Building

In contexts of scarcity, institutioning requires capacity building on social, affective, and material levels. Material challenges emerge throughout the institutioning process, including shortages of resources, materials, and infrastructure needed to achieve the objectives of a given project. Therefore, it is essential that participatory designers seek to continually build and strengthen both social and material capacities.

Action 4: Socio-material Affective Labor

This article reveals an academic gap in institutioning practices within contexts of scarcity, where power imbalances emerge in other ways than typically discussed. When public governments face resource shortages that affect their ability to fulfill public duties, they must engage with communities to prioritize policy objectives. This entails conscious articulations and rearrangements of power dynamics that prevent institutioning processes from becoming neoliberal strategies in which work is delegated to communities. Instead, public officials should seek to enhance the collective learning between grassroots communities and public governments, focusing on each actor’s respective capabilities and interests (Kaethler et al., 2017).

In the cases explored above, communities, public governments, and designers expressed their concerns regarding livability, social cohesion, and sustainable innovation even though the collaboration did not necessarily lead to more time- or budget-efficient processes, common goals of public government-based initiatives (Brinkman et al., 2023). Instead, participatory designers deeply engaged in socio-material affective labor, identifying and integrating diverse ways of caring for both humans and more-than-human actors in the process.

Action 5: Socio-material Documentation and Data Exchange

Documentation and data exchange within and across case studies are essential for connecting grassroots labor to professional work. Since existing institutioning and policy design cases have predominantly occurred in Western contexts, one of the most important outcomes of this process was a new awareness of cross-cultural learning perspectives, highlighting a substantial research gap (Mortati et al., 2022). Therefore, we consolidated knowledge across geographies to obtain additional insights. For example, scarcity driven by climate change is acutely felt in Tanzania, where governments tend to be more embedded in their local communities, leading to more in-depth socio-material collaborations between community members and policymakers. Conversely, the Living Lab in Belgium revealed the need for preliminary documentation of collective learning practices, particularly in the context of socio-material harvesting and configuring, as a foundation for future long-term collaborations in specific and localized contexts.

Connecting to Work: Structural Negotiating

Enabling structural negotiation with governments, we observed that designers were well-supported by intermediary governmental infrastructures (e.g., the MTAA office) and grassroots community infrastructures (e.g., the Living Lab), effectively creating a collective learning space. This arrangement facilitated learning from past experiences and eliminated the need to start over each time new social or material actors were brought into the process. It also provided the additional benefit of creating a lively context on which future sustainable transitions can be based.