Agonistic Arrangements: Design for Dissensus in Environmental Governance

Akshita Sivakumar

University of California, Davis. Davis, United States of America

In response to a desire for justice-based outcomes in environmental governance, there is a rise in various forms of collective governance. The dominant models include participatory and consensus-based, deliberative governance, where aspects of the environment are managed and debated between state agencies, the market, and civil society. However, these models have limitations in negotiating power between various social groups to result in transformative organization. In response, building on the political theory of agonism, design and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) have recently acknowledged the role of difference and dissensus in public sector participatory processes. The methods and effectiveness of how design can assist social movement actors in spurring and maintaining these differences to ensure just outcomes when participating in state-led governance practices remain to be studied. This article draws on over three years of fieldwork with environmental justice activists participating in California’s decarbonization program. I argue design can help with dissensus by creating space for, articulating the content of, and giving form to ways to draw out tensions that are often suspended in participatory and deliberative processes. I propose a conceptual and methodological framework called Agonistic Arrangements to draw out these tensions. These findings have implications for those involved in participatory governance in the public section across domains.

Keywords – Critical Environmental Justice, Environmental Governance, Participatory Design.

Relevance to Design Practice – This article is of critical relevance to designers interested in working with social movements for just outcomes in governance. It presents a methodology through which design practice can help resist the appropriation and de-politicization of social movements by the state and the market.

Citation: Sivakumar, A. (2024). Agonistic arrangements: Design for dissensus in environmental governance. International Journal of Design, 18(3), 105-117. https://doi.org/10.57698/v18i3.08

Received June 1, 2024; Accepted November 15, 2024; Published December 31, 2024.

Copyright: © 2024 Sivakumar. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

Corresponding Author: asivakumar@ucdavis.edu

Akshita Sivakumar is a designer, architect, and technoscience studies scholar. She is an assistant professor of Design at the University of California, Davis, where she also directs the Collective for Socio-Spatial and Environmental Praxis (CoSEP). Her work lies at the confluence of governance, social movements, participatory design, technology, and spatiality. Her current research project examines how technologies of participation impact the relationship between environmental governance and solidarities within and across the environmental justice movement in California’s efforts toward air pollution mitigation and decarbonization.

Introduction

On a hot summer afternoon in 2024, tensions ran high during a meeting at the California Air Resources Board (CARB) in downtown Sacramento, California. The gathering brought together a special advisory committee of environmental justice activists and state officials. Members of the committee, the Environmental Justice Advisory Committee (EJAC), were seated around a makeshift “roundtable” in the shape of a U at the Cal-EPA headquarters. Around the two arms of the U were seated members of the EJAC; in the connector piece sat CARB officers. “What are we even doing here? “We are stuck! We have been stuck in this place where the solutions CARB is coming up with are fundamentally not aligned with what EJ communities need,” exclaimed Martha-Dina, the co-chair of the EJAC. A calibrated and vociferous, middle-aged Latina physician and EJ leader, Martha Dina’s voice was steady, yet flustered; filled with hope, but laced with wariness—a seasoned amalgamation I had noticed amongst many environmental justice leaders over the many years of my fieldwork. Fellow EJAC members nodded in approval; some propped up their tent cards with their names and affiliations vertically on the table to signify their intention to add comments to bolster the co-chair’s frustration. The tensions echoed years-long exasperation with the limitations of the methods by which the state agency had solicited the EJAC’s expertise—through the terms of a suite of computer models. This set of computer models projected the future states of the economy, energy, air quality, and health. Martha-Dina’s dissatisfaction was not met with a response from CARB staff. Eventually, she said, “Ok, I just needed to say that. We can move on… I know we have a long agenda to get through.” Left in its wake was a sense of incomplete business, a tense wake that was another theme I became familiar with during my fieldwork.

The frustrations that Martha-Dina voiced weren’t new. Repeated in tens of other such meetings in the past, the tensions were a result of differences in worldview. On the one hand, market-based solutions assumed that justice-based outcomes would result as a by-product of the free market. On the other hand, an approach that the EJAC members wanted to see was to prioritize justice-based outcomes that moved away from the extractive nature of the free market. However, the market-based ideology was baked into the computer modeling suite that CARB used as the basis for the discussions with the EJAC. EJAC members were acutely aware of these differences. Martha-Dina also stated, “I have little faith in the pace at which the projects are being deployed without regulation; not that I have faith in how regulation works…because this is how we got here.” Yet, what Martha-Dina was doing, both tactically and unwittingly, by periodically voicing such dissonances in the meetings, was creating space for dissatisfaction in a configuration of state-led EJ work.

This vignette is just one of many telling examples of how EJ activists navigate the dominant forms of collective governance, which are procedural ways of boosting participation and deliberation that proclaim just outcomes. Processes typical of participatory and deliberative democracy claim to support inclusion and coordinated work through purposeful, liberal rationalist debate between various state and non-state actors. They typically focus on expanding the range of social actors seated at the table. They aim for and rely on cooperative and consensus-based action. As a result, tensions, such as the one described above, are often left suspended, with the discomfort quickly displaced by a procedural requirement to move on with the meeting and stick to the agenda. It is in this trope of suspended tensions, although frustrating, that a question emerged that inspired this article: How can design, rooted in commitments to justice-oriented outcomes, support opportunities and spaces for “real political possibility” (Huybrechts et al., 2017) based on agonism and difference for the re-engagement of the politics of participatory governance in the public sector? This article focuses on the role of design in extending these differences based on productive conflict to expand opportunities for just outcomes.

This article hinges on a high-stakes dilemma: On the one hand, social movement actors are wary of participating through deliberative methods to ensure just outcomes (Pulido et al., 2016). On the other hand, they fear the opportunity cost of refusing participation in favor of direct action, such as the cost of visibility and access to state resources. Given this double bind’s persistent and growing prevalence, ensuring that their participation with the state is not for naught is even more necessary. One way to do that is to prioritize dissensus rather than consensus. In conversation with and building on a growing interest in design research that examines the potential of interactive systems in social movement actions without relying on consensus (Crooks & Currie, 2021; DiSalvo, 2012, 2022; Meng et al., 2019), this article’s aim is twofold. First, to articulate the kinds of differences that design tools mediate in environmental governance. Second, advancing theories of agonism (Mouffe, 1999, 2013), contention (Tilly & Tarrow, 2015), and dissent (Rancière, 2004) in design, I propose a conceptual and methodological framework of agonistic arrangements to maintain productive conflict via design interventions in otherwise deliberative and participatory settings to better reach just outcomes. I demonstrate the capabilities of agonistic arrangements through the case of a special advisory committee’s involvement in California’s efforts to decarbonize and mitigate air pollution while explicitly committing to environmental justice and a just transition. After describing this framework’s features, I argue that careful work with groups straddling state spaces and marginalized communities, such as special advisory committees comprised of social movement actors, offers designers unique opportunities to articulate and facilitate differences that can promote significant political possibilities. I demonstrate how consensus and coordination-based participation can be made more agonistic in ways that are not currently explained nor analyzed in the literature, in turn, inviting critical designers to develop interventions that maintain pressure on more radical change.

Background and Related Work

I position the contributions of this article within a broader call for design interventions in articulating differences. I first exposit political theories of difference in participatory governance and then yoke that together with design responses to these theories of difference. The field of design has seen a recent uptick in the role of emphasizing difference to expand democracy through participatory, deliberative, and agonistic mechanisms through agonism and contention. For the purposes of this article, governance refers to the intermediate arrangements beyond those of the state and market that develop rules for behaviors and of power in democratic decision-making while seeking accountability (Bakker & Ritts, 2018; Bennett & Satterfield, 2018; Bua & Bussu, 2023; Jasanoff & Martello, 2004; Rhodes, 1996; Swyngedouw, 2005). These entities include both private actors and those from civil society. As state agencies make overt commitments to environmental justice, climate justice, and a just transition, social movements are playing a pivotal role in environmental governance. Social movement studies show a rise in the desire and need to reclaim participatory governance amidst the dilemma of participating in state efforts in fear of de-politicization of social movement action (Swyngedouw, 2005). However, participation is conceptualized differently between social movement actors and state governance agencies. While the social movement groups see it as an opportunity to have one’s community represented, the latter sees it as a fulfillment of a justice-oriented rhetoric. Political theorists Bua and Bussu call this “democracy-driven governance” (DDG). Democracy-driven governance refers to the ways that social movements are rethinking and reclaiming spaces of participatory governance in line with civic desires and demands (Bua & Bussu, 2021).

In environmental governance, like many other forms of governance, technologies such as computer models and their associated data practices are increasingly playing a central role in these deliberative processes with aims for just outcomes. Their uses are wide-ranging: from collecting input from a wider public to making projections of future states of the environment and economy, as in the technologies that I discuss later. These technologies coordinate the values of the state, market, and civil society to anticipate futures and implement programs and policies. They mediate the work of social movement and governance in DDG processes. With growing commitments to EJ at the federal and state levels, such situations are not uncommon and are only poised to rise. They are increasingly becoming the centerpiece of collective governance in the public sector, promoting consensus or coordination. How, in this technocratic landscape, can designers contribute to articulating and maintaining differences in meaningful ways?

Political Theories of Difference in Collective Governance and Design Interventions

In this section, I set up the role of design interventions in collective governance. I use the term design interventions to encompass both discursive artifacts and practices. The dominant procedural justice paradigm in the US involves democratic decision-making that relies on increasing participation and practices of deliberation. In such processes, differences between various social groups matter because they lead to varied forms of mobilization. Thus, it is worth identifying multiple political theories of difference to understand the potential for design interventions to have a political impact on collective governance, including participatory, deliberative, and agonistic. Making a case for agonistic approaches, I position them as a foil to more mainstream participatory and deliberative approaches to democratic governance.

Participatory approaches to governance prioritize increasing contributions of opinion (Lafont, 2019). It aims to democratize political institutions by increasing the diversity of representation by “giving voice” to those underserved. An underlying assumption of this approach is that communities are empowered by the mere nature of being included in democratic processes as a result of creating a more active and empowered civil society (Barnes et al., 2007; Fung & Wright, 2003). Deliberative democratic approaches, made popular by the political theorist Jürgen Habermas (2015), rely on public discourse through rational, communicative means (Mouffe, 1999) such as inter-agency consensus. Deliberative governance theorists prioritize a systems-level approach to ensure deliberation considers the variety of democratic functions across different parts and spaces of a system of governance (Berg & Lidskog, 2018; Elstub et al., 2016). In a rational and iterative process, the aim is to reach a consensus after rationally considering various points of view. In deliberative processes, a governance system is legitimized so long as civic actors are given the opportunity and the forum to express their political roles through deliberation (Lafont, 2019).

Agonistic democracy draws on the work of Chantal Mouffe and Ernesto Laclau (2001) to argue that although democratic action may require consensus in some form, consensus must not be without dissent. This dissent involves not merely rational thought but also “passions and affects” (Mouffe, 2000, p. 95) that can mobilize new solidarities. Drawing on the Gramscian proposition of hegemony, or the domination of any one social group, agonism aims to develop a counter-hegemony (Gramsci et al., 1971/1989; Mouffe, 1999). This is done by gathering power to subvert dominant ideologies institutions hold and influence business-as-usual values and norms. To Mouffe, there is no unencumbered pluralism within a democracy, whereby differences in social groups automatically create opportunities to challenge dominant ideologies (Mouffe, 2013). Further, she argues that the process of challenging dominant realities does not lie under the purview of any one kind of social struggle. Instead, counter-hegemonic practices require rearranging power due to overlapping social struggles. The philosopher Jacques Ranciére (2004) has framed dissensus slightly differently, arguing that dissensus is the prerequisite to political subjectivity. Rather than merely dissent in discourse, it fundamentally challenges what is common about the common ground with which the public sector concerns itself. “[P]olitical dissensus is not simply a conflict of interests, opinion, or values. It is a conflict over the common itself” (p.6). In environmental governance and justice domains, this conflict over the common is all the more vital. It brings into relief the need to move away from merely distributing harms or the recognition of group differences to instead consider seriously the role of culture, affect, and worldings necessary for radical inclusion and change.

Theorists of agonism critique more mainstream participatory and deliberative approaches in terms of power. For instance, participatory approaches that focus on increasing representation frequently fall prey to the reproduction of inequities through tokenism, where some marginalized members may have a seat at the table with no power (Young, 2011). Further, it can easily lead to the co-optation of labor and knowledge of the very communities participatory governance claims to boost (Fischer, 2012). In deliberative processes, social movement actors often encounter dissonances in how they conceptualize their power versus how dominant institutions do (Mansbridge, 2020). Distinctions are usually papered over, favoring consensus (Bächtiger et al., 2018; Dryzek, 2002). Deliberative processes aim to mobilize new groups (Lezaun & Soneryd, 2007), but there are seldom opportunities to disrupt business as usual. Although they account for more than increasing representation by advocating for increasing oversight of public services, such oversight can fall into the trap of more coordination-based collaboration (Dean, 2018). In their argument for agonism, Mouffe opposes this idealizing of consensus and the downplaying of conflict; Ranciére resists the traditional distribution of the political order that renders significant swathes of civil society powerless.

To position the potential for design to contribute to counter-hegemonic practices in collective governance, I exposit here how design has dealt with differences in the public sector for democratic participation. There is a growing interest in offering a wide range of civic-centered participation opportunities (Pirinen et al., 2022) and participatory governance. Those working with ‘citizen science’ have aimed to deepen encounters and increase a wider range of participants in sensing and monitoring projects to aid in validation (Gabrys, 2019; Irwin, 2002, 2018; Kinchy, 2017). These sense-making projects help with attunements but stop short of exploring foundational differences between social groups involved in governance. Designers have also explored the narrative capacity of design and its ability to provoke debates (Mazé & Redström, 2008). Keshavarz and Mazé (2013) have further explored the designer’s role as a translator in practices of ‘staging’ and ‘framing’ participatory design. They argue for conceding the designer’s power through ‘indisciplinarity,’ amounting to the defamiliarization of any dominant group’s knowledge to intervene within prevailing sensible orders.

Similarly, Lury and Wakeford (2012) propose open-ended encounters as a form of political participation. However, mere participation does not ensure equity in knowledge production because it puts data demands on marginalized groups (Crooks & Currie 2021). Further, the data that is collected via increased participation needs to be validated (Ottinger, 2010; Sivakumar, 2023), and often, validation is conceptualized in technical terms rather than sociotechnical ones. When the intention is to shift power to marginalized communities, such that neither the state nor the market is the primary center of decision-making (Black, 2008; Swyngedouw, 2005), it is vital to understand how and who makes governance work legitimate and who sets the terms for accountability. Design can articulate these processes of legitimation and accountability.

Agonistic approaches to design sit in contrast with other forms of design for collective governance. Binder et al. (2015) have formulated the concept of “democratic design experiments” that connect political institutions with experimental laboratory models. They argue that experimental forms of governance should be better integrated with existing political institutions to have an impact. While the Scandinavian model of participatory design (PD) has long favored dissensus in the workplace (Bjerknes & Bratteteig, 1995; Ehn, 1989), there is an increasing interest in prioritizing differences in data-driven and design-mediated governance mechanisms. Design studies and critical data studies scholars have begun to analyze how difference plays out in public participation, with a common goal of redistributing power. More recently, scholars have invited data practitioners to think in terms of agonism to confront the conflicting role of data in politicized projects whereby minoritized communities are caught up in the process of generating data to participate (Crooks & Currie, 2021, p. 205). Rather than merely considering data in terms of management and measurements, they instead highlight the affective and narrative potential of ‘agonistic data practices’ whereby minoritized communities can use data for contention (p. 202). Thinking of agonism spatially, scholars have considered the handing over of power between users of temporary spaces such as vacant urban plots as points of contention (Hernberg & Mazé, 2018), or gatherings within which groups can debate alternative civic configurations (DiSalvo, 2012, 2022). Design can serve a purpose beyond mere information representation. Scholars have identified the role of designed objects and democracy in terms of the ‘material participation’ of technological tools. In terms of the forms of designed agonism via material interaction for purposes beyond mere information delivery, scholars have examined the entanglement between democracy and designed objects. Science and Technology Studies scholar Noortje Marres (2012) conceptualized ‘material participation’ to explore how people engage in political processes through material, designed objects. These design objects also include protest signs that can aid engagement while promoting agonism (DiSalvo, 2012).

However, much work remains to be done to analyze the approaches to and implications for critical outcomes via agonistic design interventions in collective governance. Specifically, these questions remain to be explored: What would the features of design interventions be that create agonistic practices in governance? How can design resist the co-optation of social movement interests within the dominant collective governance models that maintain inequitable social structures by hastening consensus? Below, I explore these questions through the case of environmental justice action toward decarbonization in California, followed by the defining features of design interventions that I call agonistic arrangements.

Research Site and Positionality

To exposit the role of design in agonistic governance, I work through a case of California’s decarbonization efforts through Assembly Bill 32 (AB 32), the Global Warming Solutions Act, enacted in 2006 to achieve carbon neutrality. AB 32 mandates a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels by 2030, utilizing a mix of command-and-control regulations and market measures like cap-and-trade. The 2022 Scoping Plan aimed for carbon neutrality, building on earlier plans that focused on fossil energy and industrial emissions. I conducted ethnographic research over 18 months as part of a three-year study on the role of computing and technology in environmental governance and justice. My role was both that of social scientist and designer. I explored how various social groups within the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and the Environmental Justice Advisory Committee (EJAC) utilized mediation tools and technologies by engaging in participant observation and conducting interviews.

For the 2021-2022 Scoping Plan, CARB introduced new computer models and tasked the EJAC with developing input variables to project California’s carbon future while addressing community needs. These models, central to negotiations, were the basis of creating timelines and strategies for carbon neutrality under AB 32. CARB and the EJAC routinely invited modeling experts to explain these tools to other participants. However, as with the vignette with which this article began, there were missed opportunities to maximize the agonistic role of EJ activists within these committees. The following section explores how design can improve this engagement through an analytical and methodological framework of agonistic arrangements.

Agonistic Arrangements: Design Approach and Methodology

The many tabled tensions within EJAC meetings inspired the design intervention of agonistic arrangements, parsing out the role of design to articulate and deepen appeals to difference by EJAC members. Typical participatory methods may ask, “Who else might we invite to the table?” or deliberative methods might ask, “What variables should we add to our computing models?” However, these forms of questions take the business-as-usual political structures and sensible orders for granted. In such scenarios, designed artifacts or tools ranging from slide decks to computer models are taken for granted. The state’s records, in the form of meeting summaries and video recordings, present decision-making as successful outcomes and matters of fact rather than contestations. Christopher Kelty (2020) calls out the limitations of studying participation solely in terms of contributions to decision-making as if it were an autonomous process. To him, this process obscures the tensions within participation while prioritizing shared outcomes as a success. Similarly, as we see in the case of the EJAC, the state’s attempt to produce a participatory command-and-control solution to a more trenchant political-economic problem is informed by various contradictions of incommensurable knowledge, cultural recognition, and recognition of labor. Thus, I argue for agonistic methods to create spaces and techniques to interrupt these matters of fact presented by the state.

Agonistic arrangements are design interventions that are simultaneously opportunities, spaces, content, and forms that can articulate contentions. They can inform collective governance in ways that merely participatory or deliberative approaches fail to. They rely on the positionality of the designer creating these agonistic arrangements. As opportunities and spaces, agonistic arrangements slow down the rush to consensus resulting from time crunches, compromised values, and inadequate data endemic to mainstream forms of procedural governance. In my work, these opportunities and spaces were either meetings and workshops to which I was either invited or those I convened. As content, agonistic arrangements are designed interventions informed by coded analyses of field observations in the form of memos. Typically, in ethnographic methods that adhere to Grounded Theory, the analytical memo is written as a form of personal rumination. Facilitating discovery, they connect data, field notes, and reflective memos, leading to emergent theories from the grounded experiences of social groups (Lempert, 2007). As designed interventions, they offer this discovery back to marginalized communities and their representatives. They re-introduce dissensus through an analysis of categories and lingering questions for these groups to explicate. As form, agonistic arrangements turn analytical memos into designed artifacts to serve as a medium for collective discovery, reflection, and praxis, and a site for extending good relations across the divide of community experts and academics. I designed and printed these artifacts using risograph printing, a low-tech, low-cost, high-volume printing process popular in social movement communication design. Together, Agonistic Arrangements as opportunities, spaces, content, and form, can align with shifting the power of aligned with shifting the power of theory-building to EJ activists.

In these agonistic arrangements, my role was first of articulator, developing the design artifacts based on analytical memos, which were generated through reflexive analysis, and then of coordinator and facilitator of spaces to test out new political possibilities. In a typical agonistic arrangement, the artifacts were either projected on the screen if the meeting was on Zoom or handed to participants as physical copies if in person. I first explained the context of the artifacts by grounding them in field observations and analytical memos. What ensued was a discussion based on the content of the artifacts and emergent themes.

Agonistic Arrangements: Two instances

Below, I analyze two instances of agonistic arrangements. The first focused on the scale of the decarbonization Scoping Plan more broadly and aimed to examine the differences between the worlding implied in the computer models and that of EJ members. The second workshop focused on a specific instance of decarbonization implementation strategies through the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS).

First instance

By July 2022, the EJAC was feeling the fire of having to give their input on a complex set of computer models. They were asked to provide their feedback on which variables they would change. CARB commissioned various consultants to develop the suite of models to make projections about California’s decarbonization. These models use a risk assessment paradigm to identify vulnerability and develop more rigorous regulations. The direction of their work was predetermined by the computer modeling suite. Kevin J, an EJAC member, remarked about the complexity of the computer models and the demands on their input under a very compressed amount of time: “It’s compound in the extreme...so it’s just...really hard to answer...we need more time...(laughs nervously)....or maybe another year extension.” Despite these complexities, members of the EJAC had built their intuition toward the decarbonization models while simultaneously figuring out the models’ utility to the respective communities to whom they had a responsibility. After extensive efforts to catch up with the technical knowledge, the EJAC made recommendations. CARB claimed they were not economically viable. This outcome left a lot of desires suspended at the table and was a source of frustration for the EJAC.

Around this time, amidst deliberations about how to proceed, EJAC members had invited other specialists to help strategize how to respond to the computer modeling suite. I was invited by an EJAC member, acting in the capacity of a social scientist and designer. The meeting was attended by all EJAC members, and other allies with technical or lay expertise. While I had not convened this group, I tested out this site’s potential for hosting an agonistic arrangement. In preparation for the agonistic arrangement instance, I drew on the following analytical memo from earlier that year (i.e., July 22nd, 2022):

The question doesn’t seem to be whether models or no models; this would be a false dichotomy and an unhelpful one given the environmental governance apparatus in the US. Maps onto the non-utility of avoidance theories. What I’m noticing is that the discussion of models is thinly veiling other themes, such as EJAC’s desire for a care economy. However, whenever they bring this up at CARB meetings, these points are just met with silence and inaction <INCOMPATIBILITY>. The discussion inevitably goes back to some of the technical features of the models. EJAC members are very well aware of the limitations of centering their discussions on the modeling suite, and the technical trap of becoming overnight experts in these complex models <TECHNICAL FRUSTRATION>. Instead, could it be useful to reconnect the discussions and desires the EJAC must shed at the table with the specificities of the models? Perhaps a more capacious understanding of economic viability that focused on a care-based economy <ECONOMIC VIABILITY>. From a production-based economy to a regenerative economy. This would produce more jobs in areas that we are not currently accounting for.

CODED THEMES: Incompatibility, technical frustration, economic viability.

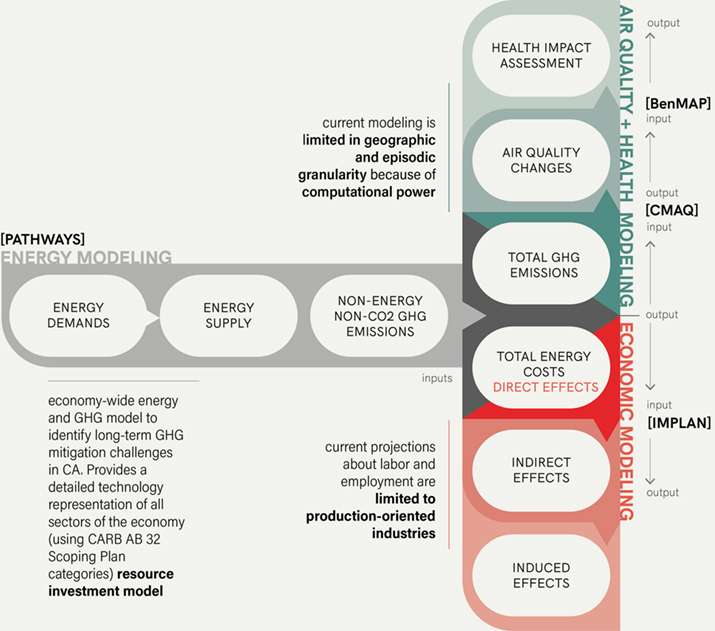

The theme from this memo—whether an approach towards decarbonization was economically viable—emerged after various iterations of conceptualization. In translating the memo into an agonistic artifact, seen in Figure 1, I focused on the differences in how the EJAC and CARB each conceptualized the economy and the relationships between the economy and air quality.

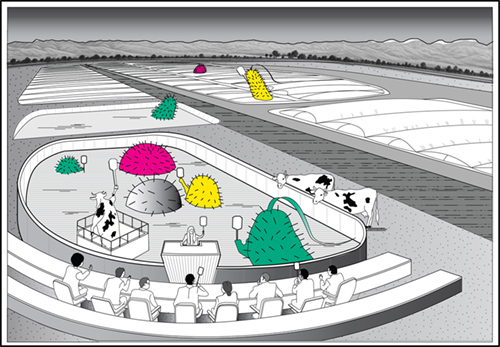

Figure 1. Examples of Designed Artifacts for Agonistic Arrangements (a) Artifact from instance #1.

The artifact synthesized content from a memo on incompatibilities, technical frustrations, and economic viability. The series of diagrams clearly laid out the sources of incompatibilities in how the EJAC and CARB conceptualized economic viability.

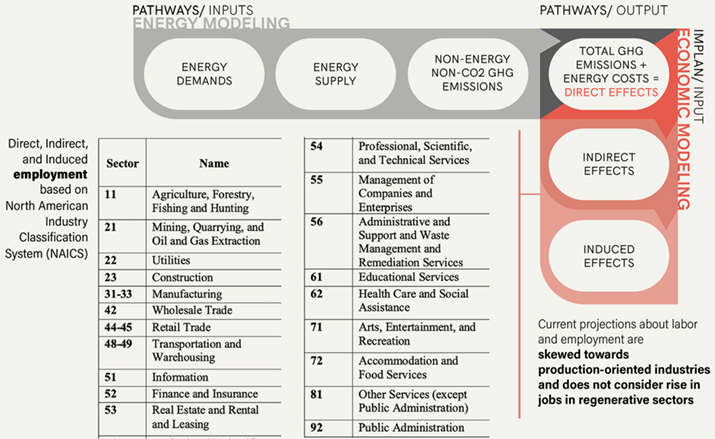

Before my presentation at this meeting, the prevailing advice of EJAC’s invited experts was to stay out of the realm of economics. One invited lawyer noted: “Remember that AB 32 is not about the economic plan for a just transition. There are other forums where we are already working on economic plans.” This advice implied that EJAC should focus on air pollution mitigation and the effects on EJ communities. However, I highlighted the need not to ignore this difference using an agonistic arrangement. I noted, instead, that while AB 32 was not an economic plan for a just transition, it was a way for CARB to justify the computer modeling scenario that would impact EJ since, by CARB’s mandate, all environmental regulations must be “economically feasible.” If the EJAC intended to make meaningful and actionable suggestions, then it would need to amplify this difference. I showed how the source of CARB’s data for economic modeling relied on labor projections of industry employment, which came from Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data. Instead, we discussed how feasibility projections should not merely account for increasing green jobs but also the community-led jobs that would be vital to successfully implement any programs that emerged from the Scoping Plan, including community oversight, education, community health engagement, and maintenance of community-led infrastructure. Through diagrams, I teased out the incompatibilities between the datasets used by CARB with the futures that the EJAC wanted to imagine. An analysis of the model suite is shown in Figure 2 to parse out these incompatibilities. I brought this discussion to the workshop to spur a more extensive understanding of what constitutes economic viability.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of how the models communicate with each other through inputs and outputs. This author-made diagram is a representation of the various models influencing CARB’s decarbonization scoping plan. It offered the EJAC an opportunity to draw connections between the economy and environment, instead of accepting the dominant approach to conceptualize these categories separately. It also allowed them to pinpoint concrete conflicts in terms of data sources without conceding to projections of the modeling done by CARB.

Figure 3. Schematic diagram of the limitations of economic modeling based on production-oriented industries rather than regenerative sectors. This author-made diagram offered an opportunity for EJAC members to dig deeper into the differences in how CARB and EJAC conceptualized the economy.

The agonistic arrangement was met with enthusiasm. The discussion revealed that the EJAC wanted to think beyond a production-based economy. The same attorney from the California NGO agreed and ensured this point of view was noted and that it would be included in the EJAC’s next presentation to the Board. A few days later, diagrams from this agonistic arrangement were used by the EJAC in its formal presentation to CARB, pointing out the limitations of the state’s modeling while calling for an option to model a regenerative economy. By revealing the fundamental differences between CARB’s and EJAC’s conceptualization of the economy within the existing model, the EJAC was able to make a case for why their recommendations for a plan for decarbonization could be viable if we were to expand economic modeling to include other forms of economy based on care and mutual support. It mapped onto their later actions to demand that CARB develop a care-based model option.

Second instance

The second instance of agonistic arrangements I detail here occurred during a workshop two years later. By this time, the EJAC had gained a solid understanding of the technical aspects of AB 32 but felt they were losing momentum and direction. They had shifted their focus from the abstract models they initially engaged with to a specific issue: the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS), an emissions trading rule. EJAC tackled the LCFS not by choice but because of how the California Air Resources Board (CARB) structured AB 32. The LCFS program encourages the use of alternative fuels through a credits-based system. It stems from a vision of a carbon-neutral future, treating various materials—like cow manure, sorghum, corn, sugarcane, etc.—as potential sources of fuel or energy feedstock. While these options might seem viable within energy discussions, they did not align with the goals of the environmental justice activists. Despite being promoted as a solution for California’s decarbonization efforts, the LCFS worsened environmental justice and public health issues related to methane emissions, negatively impacting soil conditions and contributing to unpleasant odors in already marginalized communities. Notably, it incentivized industries, particularly large dairy farms, to generate more waste for biofuel production. A debate soon emerged between EJAC and CARB over whether the state should subsidize biomethane. Originally intended as a temporary measure for industries difficult to electrify and for heavy-duty vehicles, the LCFS had become mainstream. Familiar with the issues surrounding large-scale dairy digesters, EJAC members called for phasing out biomethane credits, further complicating their role in this context.

Notably, despite regularly having to take a reactive stance, responding to CARB’s actions post-facto, the EJAC had made some significant strides over the past two years. They had convinced CARB to make them a permanent committee. However, with this win came the lingering question—what could the EJAC do, realistically, to bring about the changes that are needed? In other words, would their participation result in empty virtue signaling, inclusion without power, or deliberation with no bite? One afternoon, Dr. Catherine the other co-chair of the EJAC, and I were at lunch, sitting under a large oak tree in Sacramento. We discussed how, now that the EJAC was a year into being made permanent, it felt the need to recalibrate and shake things up to set the agenda for EJAC’s future. We saw an opportunity for me to host an agonistic arrangement with members of the EJAC. The following memo from this time (i.e., August 10th, 2023) influenced the agonistic arrangement I hosted a few weeks later.

There is a dissonance in worlds. CARB’s models see the land, animal waste, etc. in terms of extraction as “feedstock.” This extractive model is in conflict with that of many EJ activists. The EJAC is now compelled to discuss the downsides of these “renewable” energy practices on EJ communities. LCFS has the EJAC caught up in literal lagoons of effluvia. It is exemplary of the broader double bind of EJ activists who both feel the need to engage in the terms of the government agency’s science while also disengaging from it because of incompatibilities <FUNDAMENTAL DISSONANCES>.

CARB justifies LCFS and biomethane as a legitimate source of “renewable energy” because of two practices it takes for granted, that are incompatible with how EJAC conceptualizes the world:

1. Carbon auctions—an emissions management model that allows industries to pay to pollute. For instance, CARB often feels beholden to statutes. As a CARB official said “Our job is to balance the requirements and statutes”. The EJAC wants to change statues.

2. The use of data proxies as stand-ins for missing/immeasurable data in CARB’s models <SOURCES AND LOGICS OF DATA>. For instances, EJAC is contending with how CARB is modeling public health effects of communities’ exposure to methane leaks using data proxies that don’t accurately represent the full scope of the ill-effects of methane leaks in neighboring EJ communities.

To engage both CARB and EJAC, while staying with the dissonances, perhaps there’s a way to take these tropes—auctions and proxies, and revisit them through agonism to eke out the differences between the ethos of the state agency and the activists. What differences in configurations of power might we be able to articulate by imagining these terms otherwise? As the EJAC struggles to figure out its role amidst an urgent desire to drive accountability, revisiting these terms by shifting power can lead to rethinking what it means to audit differently. What might they look like; who conducts them, and to what effect?

Coded themes: fundamental dissonances, sources and logics of data.

I translated this memo into a design artifact that highlighted a potential route to assess whether there was an opportunity for the EJAC to interact with CARB beyond mere coordination and collaboration (Figure 4). The themes of auctions, proxies, and audits served as inroads to pick up suspended tensions during meetings with CARB. We discussed their premise, highlighting the inconsistencies between the worldview and relationships that the EJAC championed versus those that CARB did. For instance, CARB officials took carbon auctions as a lodestone of AB 32. Instead, we discussed what would happen if, instead of auctions for carbon credits that favored the highest bidding industries, auctions were based on other values such as bovine and soil health. Further, the gastrointestinal motility of both cows and humans could reshape how the LCFS defines leaching, broadening the proxy relationship to include a broader range of human and non-human networks. This conversation opened up an opportunity to invite groups who were interested in soil health in the state to strengthen the case of EJAC’s pushback. What made this instance agonistic was the ability to re-introduce differences in worlding to emphasize the limitations in dominant institutional narratives. It gave EJAC members concrete points of discussion to gauge whether they should continue to participate in the state’s process. This discussion mapped onto a later meeting with CARB, where Martha-Dina challenged CARB’s model of feedstock, which incentivizes waste production and flagged it as a potential site for EJAC to push for a change in CARB’s practices.

Figure 4. Examples of Designed Artifacts for Agonistic Arrangements: Artifact from instance #2. The artifact synthesized content from a memo on sources and logics of data. It inspired a discussion about relations with various human and non-human social groups and the land in ways conflictual with the state's managerial tools and logics.

Figure 5. Image from the designed artifact on proxies, auctions, and audits.

Image aided a discussion about what happens if we decenter proxies, auctions, and audits from an extractive mindset.

Agonistic Arrangements: Features

Based on the outcomes of these two workshops, I parse out three features of Agonistic Arrangements. Agonistic arrangements 1. Host suspended tensions, 2. Articulate pluralistic worldings, and 3. Extend networks of accountability.

Agonistic Arrangements Host Suspended Tensions

Agonistic arrangements hold tension in addition to holding space. Holding tension involves deconstructing the taken-for-granted aspects of procedural collective governance, such as public comments or advice by special committees, to re-politicize them, despite their proximity to hegemonic institutions. Through my fieldwork, it became clear that although the formation of a permanent EJAC was a win for California’s EJ movement, there was also an urgent need for additional space, different from those convened by the state agency, that could host the tensions that had to be suspended during EJAC meetings with CARB. These suspended tensions resulted from the rush to meet deadlines and move on from stalemates, and from the incommensurability between the state’s expert tools, such as computing models and their embedded worldviews, and those of the EJ activists. Agonistic arrangements don’t merely create space for conveying disagreement. After all, disagreements were commonplace in spaces convened by CARB. However, disagreements in those venues were often put aside, with little opportunity to either conceptualize shifts in power or reimagine worlds. Further, while hosting these tensions, agonistic arrangements turn technocratic tools into modes of political praxis and bring forth/activate other sensible orders tactically. They create an opportunity to represent the desires of EJ groups and facilitate participation that can be validated by EJ communities rather than technocrats and their technological tools.

Agonistic Arrangements Articulate Pluralistic Worldings

Agonistic Arrangements articulate new worldings. I use ‘worlding’ to refer to the material-discursive and material-semiotic ways of fostering relations (Cadena & Blaser, 2018; Spivak, 1985) both within social movements and across other governance constituents. While Currie and Crooks (2021) argue that agonistic data practices can amplify the narrative of marginalized communities (210), agonistic arrangements demonstrate another opportunity. They create settings for anticipating worlds that emerge from a departure from existing ones of both EJ communities and state agencies rather than being beholden to pre-existing relations. Agonistic arrangements offer analyses of differences to activate other worlds without conceding to the incommensurability of stories and narratives of community members vs. the measurements and projections of models. In the above case, they traced power relations within modeling practices and connected for the EJAC the computer models and the hegemonic forces within which model-based participatory governance exists.

These articulations eke out the political nature of relations and their impact of conflictual pluralisms on the social order of various groups. The EJAC had to contend with differences that resulted from how various the state and EJAC members conceptualized space, time, and scale differently and the need and desire of EJ activists to move from a paradigm of measurement for detection to one of accountability and enforcement. Chantal Mouffe and Ernesto Laclau’s (1985) conceptualization of ‘articulation’ is the process by which disparate groups can cohere under certain conditions and legitimate themselves through these coherences to form a vital component of counter-hegemonic action. Agonistic arrangements show that it takes articulation of other kinds of work that are invisible to or non-existent within dominant social orders. For instance, some members of the EJAC showed an interest in thinking about a regenerative economy rather than the current extractive economy. Combining safe, sustainable communities and an economy that works for working-class people and people of color was beyond the scope of the modeling tools. The agonistic arrangement eked out this tension between a ‘regenerative economy’ and an ‘extractive economy’ to point out the limitations of CARB’s worlding, which did not consider the rise of jobs in the regenerative sectors, including care work, education, community capacity-building, etc. towards a just transition. Similarly, many of the relationships that EJAC wanted to envision with the land and with non-humans were invisibilized by and incommensurable with the dominant paradigm of carbon markets and the cap-and-trade paradigm of CARB.

Agonistic Arrangements Activate and Extend Networks of Accountability

Agonistic arrangements lay bare the ‘perplexities of participation’ (Kelty, 2020) by amplifying social relations and political identities. They activate and reveal how marginalized groups within the EJ movement form ‘reflective solidarities’ (Dean, 1995) to resist a unified front that is easily subsumed within dominant forms of participating and deliberating with the state. Instead, they make legible the differences within the EJ movement. Deliberative mechanisms, favoring consensus, often undermine the less powerful voices. EJAC, too, faced this threat. Not all EJ communities had the same monetary, technical, and legal capacities to be equal participants when the terms of participation were set in technological terms. Agonistic arrangements offer under-the-hood connections between technological tools and social movements to build networks of accountability instead. It maintained connections between various EJ groups, wove together methods of direct action, such as protests with those of agonistic participation, and forged new networks of accountability.

In articulating differences, there is potential for new institutional possibilities. This difference is not only across “stakeholders” but also differences within social movement groups. Networks of accountability result from articulating the social relations and political identities that can grow in-situ during agonistic processes. While participatory governance prioritizes shared outcomes as a success, agonistic arrangements slow down consensus, redirect values, and inspire new solidarities. In the case of the agonistic arrangements above, the following networks of accountability were forged. I made connections between LCFS and soil health, which foreshadowed relationships with groups interested in soil storage, who were also interested in moving away from the dominant paradigm of the LCFS. Second, the author’s lab and the EJ coalition built a solidaristic relationship. Often, academic partnerships aim to offer technical capacity. Instead, we co-wrote a grant to change the conditions within which computer models are the centerpiece of EJ action with the state. We are now developing new protocols for accountability to cycle back into the state’s EJ office and in policy briefs. Agonistic arrangements are thus ways to escape the alienating nature of participatory governance as a purely technical exercise and instead maintain the potential for accountability within this process. Equally emphatically, it insists on altering configurations of power, encouraging different sources and logics of data collection and transparency, and, more importantly, building community capacity such that communities can weigh in on the utility of offering their labor to state-led EJ programs and envision new forms of accountability while altering governance structures.

Conclusion

As collective governance takes on commitments to justice-oriented outcomes, it is vital that there are shifts in power within dominant configurations between the state, market, and civil society for the efforts of participation to not merely maintain the status quo. Taking the case of environmental governance in California, this article has built on the recent rise in design work that aims for agonistic interaction and brings it to design interventions in collective governance. Mere collaboration or consensus-based participation can lead to undesirable outcomes where the state gets to claim to do the work of environmental justice while splintering the EJ movement. The article has proposed agonistic arrangements as design interventions that facilitate emergent relations between social movements and state institutions for transformative participatory governance. Agonistic arrangements are simultaneously configurations of spaces, content, and discursive objects that prioritize dissensus rather than consensus, aiming to reconfigure power in state and social movement interaction. They pluralize worldings and resist representation without power. This article has shown that social groups aiming for more just, collective governance can convert deliberative governance spaces into agonistic ones through agonistic arrangements. In doing so, social movements can splint rather than splinter. At stake for design is the ability to articulate vital differences on which just outcomes of governance rely.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for the numerous EJ activists who have built trust with me and shared their knowledge, worldings, and commitments. This work was partially supported by the National Science Foundation.

Endnotes

- In the interest of a sharper focus on the use of designed systems and ICTs, I don’t include a discussion of work aimed at improving the operations of individual groups (Vlachokyriakos et al., 2014) or those used to engage and mobilize constituents in civic action (Gordon et al., 2017).

References

- Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J. S., Mansbridge, J. J., & Warren, M. (Eds.) (2018). The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Bakker, K., & Ritts, M. (2018). Smart Earth: A meta-review and implications for environmental governance. Global Environmental Change, 52, 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.07.011

- Barnes, M., Newman, J., & Sullivan, H. (2007). Power, participation and political renewal: Case studies in public participation (1st ed.). Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qgrqs

- Bennett, N. J., & Satterfield, T. (2018). Environmental governance: A practical framework to guide design, evaluation, and analysis. Conservation Letters, 11(6), Article e12600. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12600

- Berg, M., & Lidskog, R. (2018). Deliberative democracy meets democratised science: A deliberative systems approach to global environmental governance. Environmental Politics, 27(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2017.1371919

- Binder, T., Brandt, E., Ehn, P., & Halse, J. (2015). Democratic design experiments: Between parliament and laboratory. CoDesign, 11(3–4), 152–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2015.1081248

- Bjerknes, G., & Bratteteig, T. (1995). User participation and democracy: A discussion of Scandinavian research on system development. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 7(1), Article 1. http://aisel.aisnet.org/sjis/vol7/iss1/1

- Black, J. (2008). Constructing and contesting legitimacy and accountability in polycentric regulatory regimes. Regulation & Governance, 2(2), 137–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2008.00034.x

- Bua, A., & Bussu, S. (2021). Between governance-driven democratisation and democracy-driven governance: Explaining changes in participatory governance in the case of Barcelona. European Journal of Political Research, 60(3), 716–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12421

- Bua, A., & Bussu, S. (2023). Reclaiming participatory governance: Social movements and the reinvention of democratic innovation. Taylor & Francis.

- Cadena, M. de la, & Blaser, M. (Eds.). (2018). A world of many worlds. Duke University Press.

- Crooks, R., & Currie, M. (2021). Numbers will not save us: Agonistic data practices. The Information Society, 37(4), 201–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2021.1920081

- Dean, J. (1995). Reflective solidarity. Constellations, 2(1), 114–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8675.1995.tb00023.x

- Dean, R. J. (2018). Counter-governance: Citizen participation beyond collaboration. Politics and Governance, 6(1), 180–188.

- DiSalvo, C. (2012). Adversarial design. MIT Press.

- DiSalvo, C. (2022). Design as democratic inquiry: Putting experimental civics into practice. MIT Press.

- Dryzek, J. S. (2002). Deliberative democracy and beyond: Liberals, critics, contestations. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/019925043X.001.0001

- Ehn, P. (1989). Work-oriented design of computer artifacts. Arbetslivscentrum.

- Elstub, S., Ercan, S., & Mendonça, R. F. (2016). Editorial introduction: The fourth generation of deliberative democracy. Critical Policy Studies, 10(2), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2016.1175956

- Fischer, F. (2012). Participatory governance: From theory to practice. In D. Levi-Faur (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of governance (pp. 457-471). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199560530.013.0032

- Fung, A., & Wright, E. O. (2003). Deepening democracy: Institutional innovations in empowered participatory governance. Verso.

- Gabrys, J. (2019). Sensors and sensing practices: Reworking experience across entities, environments, and technologies. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 44(5), 723-736. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243919860211

- Gordon, E., D’Ignazio, C., Mugar, G., & Mihailidis, P. (2017). Civic media art and practice: Toward a pedagogy for civic design. Interactions, 24(2), 66–69. https://doi.org/10.1145/3041764

- Gramsci, A., Hoare, Q., & Smith, G. N. (1989). Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. International Publishers. (Original work published 1971)

- Habermas, J. (2015). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. John Wiley & Sons.

- Hernberg, H., & Mazé, R. (2018). Agonistic temporary space—Reflections on “agonistic space” across participatory design and urban temporary use. In Proceedings of the 15th conference on participatory design (Vol. 2, Article no. 17). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3210604.3210639

- Huybrechts, L., Benesch, H., & Geib, J. (2017). Institutioning: Participatory design, co-design and the public realm. CoDesign, 13(3), 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1355006

- Irwin, A. (2002). Citizen science: A study of people, expertise and sustainable development. Routledge.

- Irwin, A. (2018, October 23). No PhDs needed: How citizen science is transforming research. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07106-5

- Jasanoff, S., & Martello, M. (Eds.). (2004). Earthly politics: Local and global in environmental governance. The MIT Press.

- Kelty, C. M. (2020). The participant: A century of participation in four stories. University of Chicago Press.

- Keshavarz, M., & Maze, R. (2013). Design and dissensus: Framing and staging participation in design research. Design Philosophy Papers, 11(1), 7–29.

- Kinchy, A. (2017). Citizen science and democracy: Participatory water monitoring in the marcellus shale fracking boom. Science as Culture, 26(1), 88–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2016.1223113

- Laclau, E., & Mouffe, C. (2001). Hegemony and socialist strategy: Towards a radical democratic politics. Verso.

- Lafont, C. (2019). Democracy without shortcuts: A participatory conception of deliberative democracy. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198848189.001.0001

- Lempert, L. B. (2007). Asking questions of the data: Memo writing in the grounded theory tradition. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of grounded theory (pp. 245-264). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607941.n12

- Lezaun, J., & Soneryd, L. (2007). Consulting citizens: Technologies of elicitation and the mobility of publics. Public Understanding of Science, 16(3), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662507079371

- Lury, C., & Wakeford, N. (Eds.). (2012). Inventive methods: The happening of the social. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203854921

- Mansbridge, J. (2020). A citizen-centered theory. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 16(2), 15-24. https://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.411

- Marres, N. (2012). Material participation: Technology, the environment and everyday publics. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mazé, R., & Redström, J. (2008). Switch! Energy ecologies in everyday life. International Journal of Design, 2(3), 55–70.

- Meng, A., DiSalvo, C., Tsui, L., & Best, M. (2019). The social impact of open government data in Hong Kong: Umbrella movement protests and adversarial politics. Information Society, 35(4), 216–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2019.1613464

- Mouffe, C. (1999). Deliberative democracy or agonistic pluralism? Social Research, 66(3), 745–758.

- Mouffe, C. (2000). The democratic paradox. Verso.

- Mouffe, C. (2013). Agonistics: Thinking the world politically. Verso.

- Ottinger, G. (2010). Buckets of resistance: Standards and the effectiveness of citizen science. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 35(2), 244–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243909337121

- Pirinen, A., Savolainen, K., Hyysalo, S., & Mattelmäki, T. (2022). Design enters the city: Requisites and points of friction in deepening public sector design. International Journal of Design, 16(3). https://doi.org/10.57698/v16i3.01

- Pulido, L., Kohl, E., & Cotton, N.-M. (2016). State regulation and environmental justice: The need for strategy reassessment. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 27(2), 12–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2016.1146782

- Rancière, J. (2004). Introducing disagreement. Angelaki, 9(3), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725042000307583

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (1996). The new governance: Governing without government. Political Studies, 44(4), 652–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb01747.x

- Sivakumar, A. (2023). Data surrogates as hosts: Politics of environmental governance. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 9(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.28968/cftt.v9i1.38144

- Spivak, G. C. (1985). The Rani of Sirmur: An essay in reading the archives. History and Theory, 24(3), 247-272. https://doi.org/10.2307/2505169

- Swyngedouw, E. (2005). Governance innovation and the citizen: The Janus face of governance-beyond-the-state. Urban Studies, 42(11), 1991–2006. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500279869

- Tilly, C., & Tarrow, S. (2015). Contentious politics (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Vlachokyriakos, V., Comber, R., Ladha, K., Taylor, N., Dunphy, P., McCorry, P., & Olivier, P. (2014). PosterVote: Expanding the action repertoire for local political activism. In Proceedings of the conference on designing interactive systems (pp. 795–804). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2598510.2598523

- Young, I. M. (2011). Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton University Press.