Stabilizing Design Practices in Local Government

Ahmee Kim 1,*, Mieke van der Bijl-Brouwer 2, Ingrid Mulder 3, and Peter Lloyd 3

1 Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, South Korea

2 Independent Researcher, Delft, The Netherlands

3 Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands

Design practices are being increasingly adopted by governments worldwide. Yet, barriers to design practices have been noted. Among the various barriers identified, a recurring theme is the gap between design practices and the established work practices of governments, suggesting that changes are needed on both sides—government organizations and design practices. In this paper, we present a study about how design practices become stabilized in the long term within local government organizations, drawing on organizational theory. The findings reveal that different types of legitimacy for design practices—pragmatic, moral, and cognitive—were shaped over time in different organizations, closely tied to each organization’s context and needs. Moreover, how design practices were interpreted and legitimized within an organization influenced what organizational processes and structures were developed to support them. This study demonstrates that the stabilization of design practices within government organizations is an adaptative process between the organization and design practices. We argue that this process is facilitated by the continuous efforts of design stakeholders in the organization.

Keywords – Design for Policy, Embedding Design, Legitimacy, Stabilization, Design Maturity.

Relevance to Design Practice – This paper provides insights for designers and organizational leaders to leverage legitimacy along with organizational processes and structures to diffuse design practices within government organizations.

Citation: Kim, A., van der Bijl-Brouwer, M., Mulder, I., & Lloyd, P. (2024). Stabilizing design practices in local government. International Journal of Design, 18(3), 45-59. https://doi.org/10.57698/v18i3.04

Received May 29, 2024; Accepted November 6, 2024; Published December 31, 2024.

Copyright: © 2024 Kim, van der Bijl-Brouwer, Mulder, & Lloyd. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: ahmeekim@skku.edu

Ahmee Kim earned her Ph. D. with a focus on design for policy from the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering at TU Delft. She previously worked as a postdoctoral researcher at Seoul National University and is continuing her postdoctoral research at Sungkyunkwan University. Dedicated to exploring systemic design approaches for public sector innovation, her research interests have recently expanded to include design for sustainability transitions.

Mieke van der Bijl-Brouwer is an independent researcher, teacher, and speaker. Her expertise and interests include design theory and practices for complex societal challenges, systemic design, and transdisciplinary practices and education. Mieke has worked in various research, design, and education roles across the Netherlands and Australia. Mieke is an adjunct fellow at the Transdisciplinary School at the University of Technology Sydney. She holds a Master of Science in Industrial Design Engineering from Delft University of Technology and a Ph. D. in User-Centered Design from the University of Twente, the Netherlands.

Ingrid Mulder is an associate professor at Delft University of Technology’s Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering. Her background in policy and organization sciences (MA, University of Tilburg) and behavior science (Ph.D., University of Twente), together with an early-stage research career in collaboratively making futures impacting society within the national top technology institute, has reinforced her pioneering transdisciplinary research addressing complex societal challenges. She has been (co-)principal investigator in a dozen national and European projects, pushing the envelope of the design discipline towards the public realm. As a director of the Delft Design Lab Participatory City Making, she further builds the conditions for society’s capacity to change.

Peter Lloyd (he/his) is professor of Design Methodology at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering at TU Delft, where he is also a co-founder of the Designing Intelligence Lab and co-director of the Center for Law, Design, and AI. He is Chair of the Design Research Society, President of IASDR, and former Editor-in-Chief of Design Studies. His research focuses on how language is used during broadly defined design processes.

Introduction

Design practices in the public sector are no longer a new trend. Governments worldwide have increasingly adopted design approaches to address problems of public service and policy, a practice that we refer to in the current work as design for policy (Van Buuren et al., 2020). There are over 100 Public Sector Innovation (PSI) labs that are known to be engaged in design for policy practices worldwide (Apolitical, n.d.). This reflects a growing recognition of the value of design for policy practices for innovative solutions to public challenges.

The value of design for policy practices has been highlighted by scholars from both design and policy fields. One claim is that design helps address complex challenges. Mintrom and Luetjens (2016) described a design way of reasoning, which co-evolves problem and solution spaces in problem situations, as “an approach to navigating and making sense of complexity” in public policy processes traditionally “characterized as an intendedly rational process” (p. 393). Another claim involves co-design practices with civil society stakeholders, which, as McGann et al. (2018) described, allows governments to incorporate “a more diverse range of voices and inputs into the policy process” (p. 4). The UK Design Council (2013) also stated that the user-centered design approach enhances the quality of public services. Finally, Kimbell and Bailey (2017) argued that prototyping—an iterative process in which designers test through the prototypes, learn, and refine their design ideas (Villa Alvarez et al., 2020)—can help close the gap between policy intent and implementation at different phases of the policy process.

However, despite the value of design, several barriers to design for policy practices have been noted. For instance, designers engaged in projects for the underprivileged were criticized for receiving high remuneration but lacking long-term commitment to the impact of their work (Mulgan, 2014); Epistemological and aesthetic differences between policymakers and designers were identified (Bailey & Lloyd, 2016); Some politicians perceived design practices as a threat as they are resistant to changing their traditional political approach (Apolitical, 2019); and McGann et al. (2018) also noted that while design practices can be effective for addressing minor community problems, they may “start to crumble when they are extended to system-wide challenges” (p. 16).

In these discussions, one recurring theme is the gap between design practices and established work practices within government organizations. About this gap, Deserti and Rizzo (2014) stated, “the more design practices are new to the organizations, the more the change should be relevant” (p. 86). In other words, embedding design practices in government may require changes in the government organization to narrow the gap. Meanwhile, Dorst (2015) argued that for design to be successfully implemented in a new context, such as government, design practices must adapt to that context. This implies that changes may be needed both in design practices and government organizations.

In the current work, we examine how these changes unfold as design practices evolve within government over time. While empirical studies on the evolution of design practices in government exist, most have focused on the initial stages of the evolution (e.g., Kang & Prendiville, 2018; Kimbell, 2015; Malmberg, 2017). To address this knowledge gap, we explored how design practices evolve over the long term in the local government context. Local governments offer an ideal setting for exploring the value that design practices bring to citizens’ lives, given their proximity to everyday citizen experiences. Drawing upon organizational studies, we particularly focused on how design practices become stabilized within local government organizations through gaining legitimacy and implementing new organizational processes and structures.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The next section reviews existing literature on the evolution of design practices within government from two perspectives: design studies and organizational studies. Organizational studies reveal aspects of the evolution of design practices that design studies have overlooked, namely the importance of stability. The method section outlines our case study approach across multiple local governments using publicly available documents, followed by the results section, which reports patterns in the stabilization of design practices and their implications.

The Evolution of Design Practices within Government

We will first review design studies on the evolution of design practices in government and then explore how organizational studies complement this knowledge.

Evolving Design Practices in Government Organizations: A Design Studies Perspective

Design studies primarily exhibit a value-oriented perspective on the evolution of design practices within organizations, emphasizing the creation of diverse or increased value through design practices. The public sector design ladder is a frequently mentioned model regarding the evolution of design practices within government organizations (Design Council, 2013). It applies a model of design evolution from private organizations to the context of public organizations, structured into three steps. In the first step, Design for discrete problems, the model claims that public agencies apply a design approach on a one-time basis to specific projects. In the next step, Design as capability, public officials collaborate with designers and independently use design approaches. The final step, design for policy, involves policymakers overcoming structural issues in traditional policymaking using design approaches (Design Council, 2013). This model suggests that design evolves from being used sporadically to becoming an embedded capability within the organization, creating greater value. This aligns with the typical value-oriented understanding of design maturity in design studies, as seen in the original design ladder (Ramlau & Melander, 2004), design staircase (Kootstra, 2009), and four places of design in organizations (Junginger, 2009). Although Junginger (2009) plays down the idea that a better positioning of design practices within organizations leads to greater value creation, she claimed that design approaches could transform the organization when they are linked to organization-wide problems, “changing fundamental assumptions, beliefs, norms, and values” (p. 7). The limitation of these models is that they tend to oversimplify the complexity of the evolution of design practices within organizations.

In contrast, several recent studies have revealed that design approaches are utilized in various ways within government organizations, with diverse levels of design needs and maturity across different departments. A study by Hyysalo et al. (2023) of design practices within the Helsinki City government identified 23 types of them grouped into 6 clusters, ranging from using design approaches for creating public service solutions to addressing organizational development needs. Pirinen et al. (2022), within the same organization, found that the potential and motivation to utilize design approaches varied across departments due to differing tasks. Consequently, the design maturity within these departments differed. These studies suggest that the three steps of the public sector design ladder model may coexist within a single organization and that there can be a wide range of design practices even in the highest Design for policy stage.

Elsewhere, scholars have focused on the legitimacy of design within organizations regarding the evolution of design practices. Legitimacy is defined as “the generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate” (Suchman, 1995, p. 574), and it is considered as a critical factor to the success or failure of an organization’s activities. Rauth et al.’s (2014) research on multiple corporate organizations implementing design practices over several years found that the legitimacy of design practices was established through challenging existing organizational norms. In-house designers demonstrated the utility of design practices, formed networks of design practice proponents, and created dedicated spaces or objects to legitimize design practices. The authors argued that while creating success stories of design is important, continuously aligning design with the organization’s context, expressing design in new organizational terms, and enhancing cultural and perceptual legitimacy of design are crucial.

A study by Lykketoft (2016) investigated the legitimacy of design practices within a government organization through a case study of MindLab. She emphasized the need to persuade organizational members to embrace design without dismissing their traditional ways of doing things. She identified factors contributing to MindLab’s legitimacy: receiving support from top management, adapting and behaving flexibly in organizational learning, forming a skilled team for achieving results, and having an experimental and safe physical space. However, despite these factors, she noted that MindLab’s legitimacy was continuously threatened, particularly due to the challenge of quantifying the value of design, even though its benefits were recognized. Additionally, questions were raised about whether the legitimacy of design, seemingly associated with user-centred innovation, should be universalised within government organizations or not.

Similarly, Mori and Iwasaki’s (2023) study investigated how multiple PSI labs in Finland formed legitimacy within their respective government organizations. These labs also faced difficulties in gaining understanding among organization members due to the novel thinking and doing of design approaches. They employed various strategies, which the authors categorized as promotion, collaboration, and networking. Promotion involved spreading information about design within the organization and simultaneously creating tangible outcomes. Collaboration aimed to involve diverse internal and external stakeholders in the design process to make the lab’s value recognized. Networking emphasized building relationships both within the organization among in-house designers and non-designer colleagues, and informally with top executives.

In conclusion, while research in the field of design demonstrates that the evolution of design practices within government is often linked to increased value creation, it also emphasizes the importance of acknowledging the complexity of organizational dynamics. This includes the challenges of establishing and maintaining the legitimacy of design practices within government organizations.

Evolving Practices in Organizations: An Organizational Studies Perspective

In contrast to design studies, organizational studies describe the evolution of new practices, such as design, in organizations from a value-neutral perspective, introducing the concept of stability of new practices within organizations.

Recent organizational studies understand organizational changes, such as the evolution of new practices within organizations, as complex and uncertain phenomena (e.g., Dooley & Van de Ven, 1999; Shaw, 2002; Stacey, 2018). Organizations are complex systems where the future is “determined by the interplay of all the choices, intentions, and strategies of all the groups and individuals both in an organization and in all other organizations” (Stacey, 2018, p. 152). This complex perspective reveals that organizational change emerges in the local interactions of many people in organizations, leading to the uncertainty of organizational change. Despite this uncertainty, human behavior often exhibits repetitive patterns, allowing us to “recognize with hindsight what has happened” (p. 153). While these patterns do not guarantee specific outcomes in organizational change processes, understanding them can help identify and reflect on what has happened and is happening. To explore such patterns regarding the evolution of new practices in organizations, we looked at the studies of Nicolini (2010), May and Finch (2009), and Roehrig et al. (2018). Although they describe their theories in different terms, they all view organizations as complex systems and offer complementary perspectives on how a new practice within organizations evolves and becomes stabilized within organizations.

These scholars agree on the fact that the introduction of a new practice within an organization is often led by a group of people who are interested in this new practice. The proponents experiment with the new practice through small-scale pilot projects (Roehrig et al., 2018). Nicolini (2010) argued that “the circulation of innovation [i.e., a new practice] requires work and energy that can only be provided by the interests of those involved” (p. 1013). May and Finch (2009) also described, “The production and reproduction of a material practice requires continuous investment by agents in ensembles of action that carry forward in time and space” (p. 540).

Once the value of a new practice is validated by the early supporters, it can spread to more members. Roehrig et al. (2018) noted that after testing on a small scale, a new practice begins to gain traction in the organization. Nicolini (2010) referred to this as the emergence of a bandwagon, explaining that this momentum can result from luck, intentional effort, or a combination of both. Roehrig et al. (2018) also suggested creating a learning loop, “whereby people are encouraged to observe changes in the desired direction and share this feedback with others” (p. 337). May and Finch (2009) emphasized the importance of legitimization, stating that “the work of interpreting and ‘buying in’ to that practice in relation to institutionally shared beliefs about the propriety and value of knowledge and other existing practices” (p. 543) is crucial.

Regarding legitimacy, several scholars have highlighted its importance for the diffusion of new practices. Palazzo and Scherer (2006) considered legitimacy “a precondition for the continuous flow of resources and the sustained support” (p. 71). Deephouse and Suchman (2008) suggested that legitimacy enhances the survival of organizational activities. In addition, scholars of legitimacy theory generally distinguish between different types of legitimacy. Suchman (1995) categorized them as pragmatic, moral, and cognitive. Pragmatic legitimacy concerns “self-interested calculations of an organization’s most immediate audiences” (p. 578) about the usefulness of the new practice. For example, consumers will legitimize any new practice of a company if it offers them benefits such as cost savings (Palazzo & Scherer, 2006). Moral legitimacy implies a new practice to align with “the audience’s socially constructed value system” (Suchman, 1995, p. 579). For example, corporate social responsibility activities are based on the societal consensus that businesses have a responsibility to do good in society (Palazzo & Scherer, 2006). Lastly, cognitive legitimacy means if a new practice is perceived as “necessary or inevitable based on some taken-for-granted cultural account” (Suchman, 1995, p. 582). The use of smartphones serves as a good example: in today’s society, smartphones are taken for granted, and most people consider them essential. All these types of legitimacy are both socially constructed and strategically managed. Johnson et al. (2006) described the establishment of legitimacy as “a contested process that unfolds across time” (p. 59). Suchman (1995) described that while pragmatic and moral legitimacies can be constructed through vigorously engaging organizational actors in public discussion, cognitive legitimacy largely depends on the autonomous behaviors in organizations. Legitimacy management thus involves both “passive compliance and active manipulation” (Palazzo & Scherer, 2006, p. 74).

Once a new practice gains legitimacy and spreads within the organization, it can become a new routine for that organization. May and Finch (2009) described this as institutionalization, normalization, or stabilization, “the point where [a new practice] has become generally habituali[s]ed” (p. 537) by being “embedded in the matrices of already existing, socially patterned, knowledge and practices” (p. 540). Roehrig et al. (2018) noted that organizational leaders can set up new structures and processes to institutionalize the new practice. They defined the organizational structures and processes as below.

Structures include anything to do with how work is divided up and coordinated. They are all the variables about how tasks and roles are designed, how work is coordinated, how people are grouped, and how authority is allocated. Processes are both formal and informal aspects of the organization that guide or channel behavior, including policies, procedures, rules and regulations, reward systems, norms, values, beliefs, culture, and “what your boss pays attention to” (p. 340).

In the presented study, we use the term stabilization instead of institutionalization or normalization. Given that organizations are complex systems in which simultaneous change and stability flow (Roehrig et al., 2018, p. 330), stabilization seems more appropriate.

To synthesize the two perspectives of design studies and organizational studies, recent studies generally recognize that the evolution of design practices within organizations is a complex process. Organizational studies highlight the stabilization of design practices within organizations, a dimension not fully addressed in design studies. In light of this, the current study aims to address the question of how design practices become stabilized within local government organizations.

Method

To investigate the stabilization of design practices within local government, we examined multiple local governments using a case study approach, well-suited for investigating multiple cases within a defined research unit. In our study, the research unit is what organizational members have said and done in the evolution of design practices within organizations. Based on the organizational studies discussed earlier, we focused on two key aspects of the stabilization process: the establishment of legitimacy and the development of organizational processes and structures to support design practices. Our research questions were:

- What legitimacy has been established for design practices, and how has it evolved over time?

- What new processes and structures have been developed for design practices, and how have they evolved over time?

This study was planned as a qualitative study to gain an in-depth understanding of the research questions. Since we were interested in the long-term evolution of design practices across multiple organizations, we chose a document-analysis approach that provides both a longitudinal and broad perspective on the evolution of design practices. This approach is suitable for similar historical research (Bowen, 2009). Data was collected by harvesting publicly available documents produced through routine reporting by local governments. These documents included organizational websites, council meeting minutes, blogs of public sector innovation labs within the organization, organizational news, project documents, organizational strategy documents, and so forth.

Case Selection

We searched for suitable cases from the global PSI lab directory, literature, and our academic networks. A list of candidates was made with the following criteria considered: 1) governments of English-speaking countries, 2) organizations that had been cultivating internal design capabilities for more than three years (because governments new to design may not have many activities to analyze), and 3) availability of publicly accessible online documents related to design practices. Cases were chosen based on varying years of building design capability within the organization. The underlying assumption was that by comparing organizations with different levels of experience of design practices, the evolution of design over time could be more clearly demonstrated. This study presents three out of five cases from the first author’s doctoral thesis (Kim, 2023) to showcase the aspect of stabilization (see Table 1). The selected cases were all from Western countries, which limits the generalizability of the results. This will be discussed further in the discussion section.

Table 1. Description of selected cases.

| Case | New York City | Auckland City | Kent County |

| Country | USA | New Zealand | UK |

| Local Population | 8m | 1.66m | 1.5m |

| Number of Employee | N/A | 10,100 | 9,800 |

| Year of PSI Lab Launch | 2017 | 2015 | 2007 |

| Name of PSI Lab | Service Design Studio | Co-Design Lab/ TSI | SILK |

| Size of PSI Lab | Less than 5 staff | 10-15/40+ staff | Less than 5 staff |

Data Collection

The data collection consisted of (1) selecting documents related to design practices in the local government’s online database and (2) examining the selected documents to find the data that addressed the research questions.

During document selection, online databases were searched using keywords from the literature, such as service design, co-design, co-production, participatory design, and co-creation. As the search progressed, it became clear that each organization used its own terms for design practices. For instance, service design was a term used by the NYC government, while the Kent County government used human-centered design. These new terms were incorporated in further searches, allowing us to complement the initially limited selection of keywords. All documents examined in this study are presented in Appendix 1.

Once 20 to 30 documents were selected per organization, the next step was identifying data to explore the research questions. To answer research question 1, we examined why each organization established a PSI lab and how the organization’s documents have described or evaluated the lab over time. To answer research question 2, we looked for the development of formal and informal roles, positions, teams, organizations, and processes related to design practices over time. This data collection was executed in 2020.

Data Analysis and Reporting

Several strategies were employed for data analysis. First, coding and thematic generation were guided by the research questions and organizational studies mentioned earlier, involving an iterative process of coding and theme development (see Table 2). Second, the document analysis revealed meta-data such as the author (whether by in-house designers or non-designer employees) and the document’s date. These meta-data helped us understand the chronological order of what was said and done regarding design practices, and who discussed design practices within the organization. Repeated similar descriptions by both designers and non-designer employees became grounds for identifying the legitimacy of design practices. Third, data were organized chronologically to track the evolution of design practices. We visually displayed coded data on Miro for cross-case analysis to identify repeated patterns.1 Fourth, document analysis required caution in interpretation, as it did not provide sufficient background information. We supplemented findings with additional internet searches or by cross-referencing multiple sources. For example, although not presented in the current paper, the first author’s thesis (Kim, 2023) investigated whether the changes in legitimacy and organizational processes and structures aligned with the actual implementation of design practices in the organization. The data related to this is included in Appendix 2. Throughout the analysis, three researchers (co-authors) besides the first author participated, providing “both confirmation of findings and different perspectives” (Carter et al., 2014, p. 545).

Table 2. Example of coding and thematising process.

| Theme | Code/ Sub theme | Sub-Code | Example Quote | Doc |

| In the Auckland City government, the legitimacy of design is established as a morally good practice that embraces and empowers ethnically diverse citizens. | Co-design is promoted as a community- empowering approach | Mayor promoting empowered community approach | Under the Long Term Plan 2015-2025, the Mayor’s proposal challenged Auckland Council to develop and apply a more empowered communities approach to its work. | doc.06-2015 |

| Co-design as an empowered community approach | Work with local boards to deliver Local Board Plans using a more empowered communities approach for initiatives such as co-design and delivery, community placemaking, asset transfer, and social enterprise… | doc.06-2015 | ||

| Co-design continues to be described as a community-empowering, inclusive, and good approach | Whānau centric co-design | Participants from community organisations, local and central government gathered in Manukau for a three day co-design experience hosted by the Auckland Co-design Lab (the Lab) and The Southern Initiative (TSI).… Whānau centric co-design…Whānau have the autonomy to decide how and when they will participate…co-decide as well as co-design. | doc.11-2017 | |

| Co-design shifts power dynamics | For some whānau and frontline workers, the co-design process represented a profound shift in power dynamics, creating an opportunity to be heard, exercise expertise and work more closely and on even footing with other stakeholders, policy makers and contract managers. | doc.15-2019 | ||

| Co-design as a good inclusive practice | This means putting a diversity and inclusion lens on our community engagement and participation actions…. We have several pockets of good and developing practice across these areas. These includes … co-design/co-creation work with communities led by the Community Empowerment unit and the Southern Initiative… | doc.13-2019 | ||

| Auckland, ethnically super diverse city | Auckland is a super-diverse city and is home to people from more than 200 different ethnicities. The scale of the city’s ethnic diversity is significant, nationally and internationally… | doc.13-2019 | ||

The findings were reported as individual case analyzes and a comparative analysis. In individual cases, we descriptively conveyed events related to stabilizing design practices by directly quoting what organizational members have said and done. In contrast, the comparative analysis took a more analytical approach, identifying patterns in stabilization processes (i.e., legitimacy, organizational processes and structures) through cross-case comparisons.

Limitation of Research Method

The limitation of this study stems from its reliance on document analysis. As part of a doctoral research project that explored the evolution of design practices within five local government organizations (Kim, 2023), the current study was unable to include additional data collection methods, such as interviews, due to the large volume of documents collected. We also acknowledged that document analysis is recognized as a valid standalone research method for tracking complex phenomena like organizational change (Bowen, 2009). That said, the validity of the findings could have been enhanced if a process of verifying the results with organizational members had been included. In addition, open data practices vary between governments (Kierkegaard, 2009), and time delays in document availability are possible. This means our study may not include the most up-to-date or complete data on design practices within the organizations.

Findings

Case 1 Description: New York City Government

The NYC government had an innovation unit called NYC Opportunity under the Mayor’s Office. Since 2014, NYC Opportunity had worked with external designers on a project basis to “explor[e] how service design can advance financial inclusion” (doc.02-2017) for low-income residents. It engaged in four projects in this period: ACCESS NYC, Growing Up NYC, Queensbridge Connected, and HOME-STAT. The first two projects were about designing digital platforms for citizens to easily access certain public services. The third project concerned “bring[ing] free broadband service to five New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) housing developments” (doc.10-2020). The last project, HOME-STAT, addressed the issue of homelessness in the city. It was stated that these projects “demonstrated the value of using human-centered design methodology to inform service” (doc.02-2017).

In 2017, NYC Opportunity established a design unit called the Service Design Studio to “institutionalize a replicable approach, which directly harnesses the unique insights and experiences of public services users to design and deliver … public services.” (ibid.). The Studio’s mission was described as “helping the City further engage with residents and those who deliver services so that their insights can shape new and existing programs” (doc.01-2017). In particular, it was stated that “44.2% of New Yorkers live at or near poverty”, and design approaches will help “mak[e] public services for low-income New Yorkers as effective and accessible as possible.” (ibid.). These data indicate that the usefulness of design approaches in creating user-centered public services for low-income citizens was validated through four projects, leading to the internal establishment of a new unit to institutionalize design approaches. As Suchman (1995) noted, pragmatic legitimacy is shaped by “self-interested calculations of an organization’s most immediate audiences” (p. 578). Applying this concept to the NYC case, we identified the establishment of pragmatic legitimacy for design practices as they proved useful in designing effective and accessible public services.

As to the new processes and structures for design practices, in the same year of the Service Design Studio’s launch, the Mayor’s Office created “a new procurement tool for hiring and working with outside design firms” for their employees “to more easily create and deliver effective, efficient, and equitable public services” (doc. 04-2017). In 2020, a department (Administration for Children’s Service, ACS) that had previously collaborated with the Service Design Studio issued a request for proposals worth $3 billion, “incorporating an end-user focus and components of service design, hiring a design consultancy for a future service design project” (doc.10-2020). It was stated that this request for proposal would “ensure that the service design is incorporated into not just ACS, but also the providers with which they work” (ibid.). ACS also established “a design learning community to spread service design learning among agency staff” (ibid.). These organizational processes and structures were developed within the first three years after the launch of Service Design Studio. These changes aimed to gain traction for design practices within the organization during the initial years. We see these efforts as different from later attempts to integrate design into the organizational system after several years of practice, as demonstrated in the following two cases.

Case 2 Description: Auckland City Government

The Auckland City government had two units that appear to be engaged in building design capability within the organization: The Southern Initiative (TSI) and Co-Design Lab. TSI was established in 2012, but no clear information was identified relating to when and why they started to engage in design practices. TSI was established as an initiative for the development of South Auckland with a social focus: “stable homes and families, skills development, job growth and housing and environmental enhancement” (doc.03-2012). South Auckland was described as an area known for “disparities in key indicators, including income, education, employment, child and youth wellbeing and outcomes for Māori and Pacific communities” (doc.22-2018). The Co-Design Lab was established in 2015 with the central government’s support “to explore solutions to some of New Zealand’s most complex and persistent challenges” (doc.04-2015). The Lab stated their aims as “to use co-design principles and practice to work with, better understand and empower the people closest to the issues” and “to create a space for multi-agency teams to collaborate, work alongside citizens” (doc.01-n.d.). The Lab was placed with TSI in South Auckland. The lab had the first 27 months of the Proof of Concept period, in which the Lab “support[ed] five project challenges, a number of which [would] focus on South Auckland” (doc.04-2015).

While there were no records of how the proof-of-concept projects were evaluated, evidence for the pragmatic legitimacy of design was found in the document describing the ‘I Am Auckland’ program. This program was “a strategic action plan for Auckland’s children and young people,” under which multiple goals such as “belonging, health & wellbeing … [career] opportunity” had been pursued (doc.10-2017). Since this plan was adopted in 2013, “the council and council-controlled organizations (CCOs) [had] delivered more than 200 discrete actions, policies or programs” (ibid.). Its 2017 program report stated that a critical success factor of many initiatives over the past years was “intentional co-design or robust engagement with young people, a range of internal and external stakeholders, businesses, iwi2 schools and community groups” (ibid.). The recognition that co-design practices were a critical success factor in various programs for children and young people suggests the acknowledgment of the usefulness of design practices. In other words, it indicates that the pragmatic legitimacy of design had been established among the program’s stakeholders.

We also identified indicators of the emergence of the moral legitimacy of design practices in this organization. A document from the year the Co-Design Lab was founded (doc.06-2015) proposed that the organization should embrace “a council-wide approach to empowered communities.” The “empowered communities approach” was explained as one that enables “communities [to] have the power and ability to influence decisions, take action and make change happen in their lives and communities.” In this document, co-design was promoted as one of such approaches: “Work with local boards to deliver Local Board Plans using a more empowered communities approach for initiatives such as co-design and delivery.” Since co-design was described as the empowered communities approach in 2015, design has been referred in multiple documents of different years (written by designer or non-designer employees) as a community-empowering and inclusive practice. In design training, the Co-Design Lab taught Whānau-centric co-design principles that emphasize the indigenous community’s decision-making power and autonomy in design processes (doc.11-2017). Co-design was described as a good practice for “putting a diversity and inclusion lens on … how we design and deliver services” in the city of Auckland, “home to people from more than 200 different ethnicities” (doc.13-2019). In addition, a couple of project reports (doc.14-2019, doc.15-2019) described stories of indigenous people experiencing subverted power relations with the city government through co-design practices, as seen below.

For some Whānau and frontline workers the co-design process represented a profound shift in power dynamics creating an opportunity to be heard, exercise expertise and work more closely and on even footing with other stakeholders, policymakers and contract managers (doc.15-2019).

The moral legitimacy of organizational activities pertains to whether they align with the socially constructed value system (Suchman, 1995). The above multiple pieces of evidence illustrate a city with diverse ethnic groups, community-empowering and inclusive practices are highly valued, and co-design has been recognized and practiced as one such practice. This suggests the potential for design practices to establish moral legitimacy as a community-empowering and inclusive practice within the Auckland City government.

Regarding what new processes and structures developed to support design practices, two types of change were identified. One concerned commissioning, which can be a process to support local government’s co-design practices with civil society stakeholders.3 Since 2019, the Co-Design Lab and TSI have raised questions such as: “How might we set up contracting and commissioning processes for experimentation and learning” (doc.15-2019) and “How might we develop and test commissioning models that increase capacity and strengthen local infrastructure” (doc-16-2020). However, there was no data that these discussions have taken shape yet. Another structural change identified was the expansion of TSI to another area of Auckland City. TSI was described as a “place-based innovation hub” (doc.20-2020), as it was established and funded by the Auckland City government but placed in South Auckland. It was described that their work is grounded in the place, and their mission is “tightly connected to the current and future wellbeing” of the place (ibid). According to the 2020 TSI evaluation report, TSI had grown “from a relatively small team of a dozen or so people, to over 40 staff” (ibid.). Additionally, the city government extended the place-based innovation model to West Auckland. Authors of the evaluation report claimed that the relation of TSI to the city government could be a new structure of “networked organization to undertake complex systemic work” as a dual operating system: TSI as “the networked structure can effectively focus on rapid and transformational change agendas, while [the city government as] the traditional hierarchy … can manage the day-to-day structured activities with efficiency, predictability and effectiveness” (ibid.). These changes in process and structure appeared 4-5 years after the organization’s launch of the Co-Design Lab. The consideration of commissioning that supports experimentation and learning, along with the expansion of the TSI model to another area, appears to be efforts to further solidify these practices based on several years of co-design with the communities.

Case 3 Description: Kent County Government

Kent County was the first local government in the UK to establish a PSI lab, the Social Innovation Lab Kent (SILK). An interview article with the founder of SILK explained that the adoption of design practice was somewhat exploratory at the time. In the excerpt below, she explained that the organizational leaders were interested in disrupting things in the organization.

“I think they were interested in doing policy differently, of disrupting things a bit. He (Assistant Director of the Council) had been aware of the work I’d been doing at Demos around co-production and service design and wanted to see how this could be applied in their context” (doc.11-2015).

When SILK was set up in 2007, its aims were expressed as twofold. First, to tackle “some of [their] most intractable social problems, using a ‘person-centered’ approach,” and second, to “build the whole organization’s capacity to start with people, rather than existing services” (doc.04-2009). In the early years, SILK had two demonstration projects “to understand how to make a person-centred approach work specifically in the context of local government” (doc.04-2009). One of the demonstration projects was the Parkwood project. This was a series of mini-projects—Just Coping in 2007, Bulk Buy in 2009, and Time Banking in 2010—with families in Parkwood estate in Kent to “look at low-income families and day-to-day life from their perspective” (doc.06A-2011). SILK worked with community organizations and residents in these projects. The project outcome of Bulk Buy was an open community space, in which the Parkwood residents could have “easier access to bulky products at a cheaper price” (ibid.). Its report stated, “This project [was] about exploring co-production in practice” (ibid.). Explicit data regarding the evaluation of this project was not found, but the activities of SILK continued within the organization after this exploratory period. In this respect, we consider that pragmatic legitimacy had been established among design stakeholders in this organization.

Furthermore, we found indicators of the emergence of cognitive legitimacy of design practices in this organization. Suchman (1995) described that the cognitive legitimacy of a new practice concerns whether the new practice is perceived as inevitable or necessary based on broadly shared taken-for-granted assumptions in organizations. The data suggest that cognitive legitimacy for design could be established as a necessary practice for public service transformation within this organization. In 2010, a document suggested that the Kent County government needs a “radical change in regard to how services are delivered,” faced with an “aging population, increased personalization, and rising customer expectations … [as well as] financial crisis” (doc.05-2010). It stated that the “future will be focussed around the co-design of local services by individual users” (ibid.). In 2013, another document, “Facing the Challenge: Whole-Council Transformation” (doc.07-2013), proposed a new service delivery model. This new model was about the organization “working with partners across the public, private and voluntary sector to improve the economic, social, health and environmental quality of life of Kent residents” as well as “[having] a greater customer focus with services organized around the needs of service users and residents” (ibid.). It was also stated that “KCC (Kent County Council) will be a commissioning authority,” meaning that services would be commissioned to “the range of providers, either in-house or external, across the public, private and voluntary sector that have the capability to deliver these [service] outcomes” (ibid.). Again, in 2014, it was stated that KCC “seeks to create integrated services that are co-designed with service users” (doc.08-2014). These data show that, when faced with multiple challenges, transforming the public service model was critical for the organization, and co-design was highlighted as a key practice in the new model. In other words, design was seen as useful and a necessary practice for addressing organizational challenges.

Regarding what new processes and structures developed to support design practices, several were identified. In 2015, a new division was created in the organization by bringing together multiple functions in one team—health and safety, business partners, engagement and counseling, organizational development, communication, human resources, etc. This integration of functions was explained “to ensure a clear and seamless alignment to support the principle of customer-centric services.... [and] to facilitate better collaborative working” (doc.13-2016). In 2016, the Design and Learning Centre for Clinical and Social Innovation was established. The Centre’s goal was described as “promot[ing] new ways of working through co-design” and “work[ing] with voluntary and private services to achieve an integrated system that crosses the boundaries between primary, community, hospital, and social work” (doc.17-n.d.). In 2017, a new Strategic Commissioning division was launched within the Strategic and Corporate Services Directorate. The directorate’s goal for 2018-19 was stated as “embedding cultural change and co-design principles into our new delivery models, including the Strategic Commissioning operating model” (doc.14-2018). These changes in processes and structures developed after many years of implementing design practices within the organization. We identified these changes in organizational processes and structures as efforts to routinise and to make design practices habitual in the organization after many years of practices.

Cross-Case Analysis

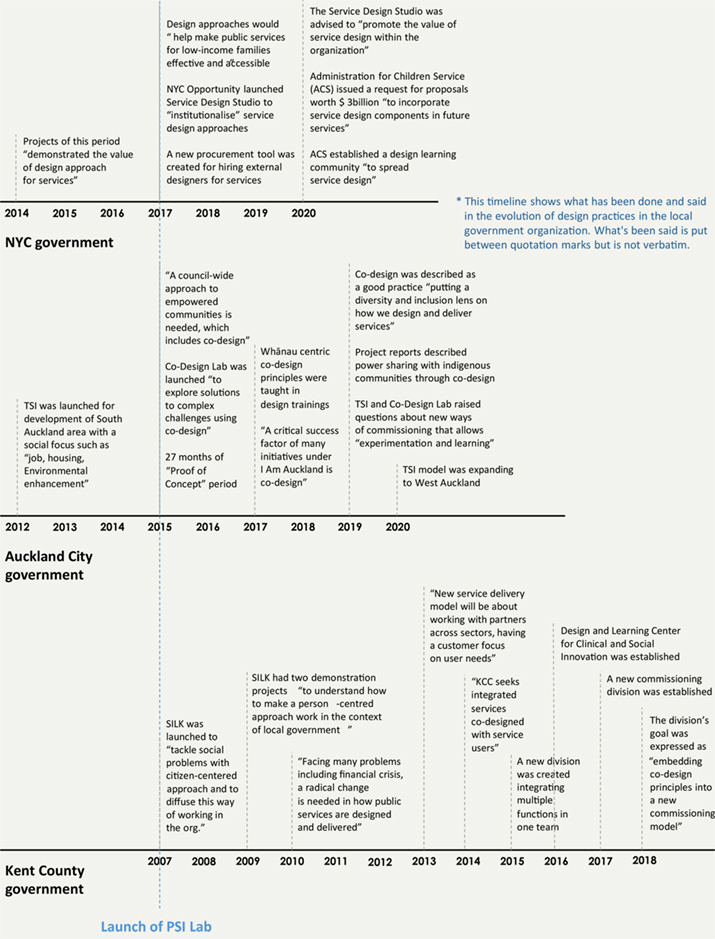

In the comparative analysis, we identified similarities and differences in the establishment of legitimacy and the development of new processes and structures for design practices over time in the three local governments. This was analyzed following the timeline, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Timeline of events in the stabilization of design practices in three local governments.

(Click on the image for larger version.)

The Evolution of Legitimacy

Regarding the legitimacy of design practice, we found that design stakeholders in all three local government organizations typically underwent an experimental period during the early years of design practices to validate the usefulness of design practices. In the NYC government, the four projects before the launch of the Service Design Studio exemplify this. In the Auckland City government, a 27-month proof-of-concept period was assigned when the Co-Design Lab was launched. In the Kent County government, SILK had two demonstration projects. In all cases, design practices continued after this experimental period, indicating that the usefulness of design had been proven to design stakeholders within the organizations. In other words, this suggests the establishment of pragmatic legitimacy.

In comparison, moral and cognitive legitimacies gradually developed as design practices became connected to the organization’s context and needs. In the Auckland City government, embracing the value of inclusivity towards indigenous and diverse ethnic groups was crucial, and co-design was recognized as a means to implement this value. In Kent County government, service transformation was deemed critically important due to the organization’s financial issue, and in this transformation, co-design was described as a necessary component. In our study, it was not possible to discern whether the moral and cognitive legitimacies of design had been fully established or were still in the process of being shaped within these organizations. However, the data demonstrate that moral and cognitive legitimacies can be constructed over time within local government organizations, respectively, as an inclusive and community-empowering practice, and as a necessary part of service transformation. The implications of these varying types of legitimacy for design practices are discussed later.

The Evolution of Organizational Processes and Structures

In terms of new organizational processes and structures that support design practices, we identified several types of processes and structures that developed over time across the three local government organizations. As seen in Figure 1, in the NYC government, the same year the Service Design Studio was established, a procurement tool was created to hire external service design resources. Three years later, a department introduced a request for proposal to include service design elements in service delivery, and an internal community for learning about service design was established. In the Auckland City government, after the Co-Design Lab was established, discussions about commissioning to support experimentation and learning with the community began in the fourth year, and in the fifth year, the government expanded TSI, a place-based innovation hub model for collaboration with local stakeholders, to another area of the city. In the Kent County government, from the eighth year onwards, new teams and an organization were created to support customer-centric services and co-design with the community.

These data demonstrate that the integration of design practices into an organization’s system through new processes and structures does not happen all at once after design practices have fully matured. Instead, it occurs through the accumulation of continuous efforts over time. In other words, in the early stage of design practices, processes and structures were developed to spread design practices within the organization, while in the later stage, they were developed to routinise the design practices, which had been validated over the years within the organization. We identified the processes and structures observed in NYC as representing the early stage, those in Auckland City as the intermediate stage, and those in Kent County as the later stage.

Contextualising for Stabilization

As we examined above findings, we found that the stabilization of design practices in local government organizations is closely linked to the context and needs of each organization. In the NYC government, where around 40 percents of the population lives under or near poverty, design was interpreted as a practice supporting services for low-income citizens. In the Auckland City government, where 200 different ethnic groups reside, design was viewed as a practice empowering local communities, including indigenous populations. In the Kent County government, where a financial issue made the transformation to new public service models critical, design was understood as a practice supporting this transformation. Furthermore, these interpretations influenced the development of processes and structures for design practices. In the NYC government, processes and structures emerged to support service design. In the Auckland City government, a place-based innovation model was developed in the area with major indigenous populations. In the Kent County government, new teams were created within the organization to support the new public service model. This demonstrates how design practices are interpreted and legitimized within an organization is closely linked to the organizational processes and structures developed to support them.

Discussion

In the current study, we examined what types of legitimacy have been established for design practices, the organizational processes and structures developed to support them, and how both have evolved across three local government organizations.

The results showed that the legitimacy of design practices is shaped differently in each organization, and various types of legitimacy can develop over time. Furthermore, how design practices are interpreted and legitimized within an organization influenced what organizational processes and structures were developed to support them. These findings suggest that the evolution of design practices in government organizations involves mutual adaptation between the organization and the design practices. For example, in the Auckland City government, design was interpreted as a practice connected to the organization’s need to embrace community-empowering practices in the context of a multi-ethnic city. This interpretation, though not shown in the current study but seen in the first author’s thesis (Kim, 2023), led to co-design practices with community stakeholders as partners. Subsequently, these design practices contributed to the growth and expansion of the place-based innovation hub model.

Moreover, our study has shown that this adaptation takes many years and requires continuous efforts from design stakeholders within the organization. Regarding legitimacy, we found that merely demonstrating the usefulness of design practices within government organizations may not be enough. While pragmatic legitimacy, as emphasized in previous studies (Lykketoft, 2016; Mori & Iwasaki, 2023), was established relatively early in the evolution of design practices, moral and cognitive legitimacies took longer to develop. These latter types of legitimacy may be more important than pragmatic legitimacy, as they appeal to the organization’s value system and the subconscious level of its members, thereby increasing the likelihood that design practices will be sustained within the organization (Suchman, 1995; Palazzo & Scherer, 2006). This ongoing effort also applies to creating new processes and structures to support design practices. Different types of organizational processes and structures should be considered depending on the maturity of design practices within the organization, for example. In summary, design stakeholders could continuously shape discourse that aligns organizational needs with design practices while making efforts to integrate them into the organizational system as they evolve.

Given the study’s limitations regarding the number of cases and its focus on Western countries, we acknowledge that the manifestations of pragmatic, moral, and cognitive legitimacies of design practices, as well as the organizational processes and structures supporting them, identified in this study are not exhaustive. Further research is needed on this topic across different cultural and political systems. Additionally, due to the reliance on document analysis, this study provided a bird’s eye view of the stabilization of design practices. To better understand the complex dynamics involved in the stabilization of design practices within government organizations, further research using more in-depth data collection methods, including interviews, will be required.

Conclusion

The current study explored the stabilization of design practices within governments. Drawing on organizational studies, we investigated what legitimacy and organizational processes and structures for design practices emerged, and how they evolved over time in multiple local government organizations. The findings revealed that stabilizing design practices in local government is a process of mutual adaptation between the organization and design practices. This study offers insights for designers and organizational leaders to leverage legitimacy along with organizational processes and structures to diffuse design practices within government organizations. Future research is needed on how the legitimacy of design is interpreted and established in different cultural and political contexts, and what supporting organizational processes and structures emerge as a result.

Endnotes

- 1. The process of this research method was published as a separate paper. Please refer to it for further details (Kim et al., 2021).

- 2. Meaning extended kinship group, tribe, or nation in the Māori language (Te Aka, n.d.).

- 3. Commissioning is a typical way for government organizations to work with external actors such as “private sector firms … other public sector organizations, third sector organizations or cross-sector partnerships” (Loeffler & Bovaird, 2019, p. 243). Commissioning does not always include design practices. However, according to Mintrom and Thomas (2018), commissioning together with design practices can improve understanding of users and local contexts and narrow the gap between policy and its expected outcome.

References

- Apolitical. (n.d.). Government innovation labs–A global directory. Retrieved from https://apolitical.co/pages/government-innovation-lab-directory

- Apolitical. (2019). Public innovation labs around the world are closing–Here’s why. Retrieved from https://apolitical.co/solution-articles/en/public-innovation-labs-around-the-world-are-closing-heres-why

- Bailey, J., & Lloyd, P. (2016). The introduction of design to policymaking: Policy lab and the UK government. In Proceedings of DRS international conference on future focused thinking (pp. 3619-3633). DRS. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2016.314

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27-40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., Dicenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545-547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

- Deephouse, D. L., & Suchman, M. (2008). Legitimacy in organizational institutionalism. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 49-77). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849200387.n2

- Deserti, A., & Rizzo, F. (2014). Design and organizational change in the public sector. Design Management Journal, 9(1), 85-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmj.12013

- Design Council. (2013). Design for public good. Retrieved from https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/fileadmin/uploads/dc/Documents/Design%2520for%2520Public%2520Good.pdf

- Dooley, K. J., & van de Ven, A. H. (1999). Explaining complex organizational dynamics. Organization Science, 10(3), 215-376. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.3.358

- Dorst, K. (2015). Frame creation and design in the expanded field. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 1(1), 22-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2015.07.003

- Hyysalo, S., Savolainen, K., Pirinen, A., Mattelmäki, T., Hietanen, P., & Virta, M. (2023). Design types in diversified city administration: The case city of Helsinki. The Design Journal, 26(3), 380-398. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2023.2181886

- Johnson, C., Dowd, T. J., & Ridgeway, C. L. (2006). Legitimacy as a social process. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 53-78. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.32.061604.123101

- Junginger, S. (2009). Design in the organization: Parts and wholes. Research Design Journal, 23-29. http://www.svid.se/sv/English/Design-research/Design-Research-Journal/

- Kang, I., & Prendiville, A. (2018). Different journeys towards embedding design in local government in England. In Proceedings of the conference on service design (pp. 598-611). Linköping University Electronic Press. https://ep.liu.se/ecp/150/049/ecp18150049.pdf

- Kierkegaard, S. (2009). Open access to public documents–More secrecy, less transparency! Computer Law and Security Review, 25(1), 3-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2008.12.001

- Kim, A. (2023). Embedding design practices in local government: A case study analysis [Doctoral dissertation, Delft University of Technology]. TU Delft Research Repository. https://doi.org/10.4233/uuid:0be72865-8064-4120-8103-c57b1321a3f0

- Kim, A., van der Bijl Brouwer, M., Mulder, I., & Lloyd, P. (2021). A document-based method to study the evolution of design practices in public organizations. In G. Bruyns & H. Wei. (Eds.), [ ] With design: Reinventing design modes (pp. 3010-3031). Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4472-7_195

- Kimbell, L. (2015). Applying design approaches to policy making: Discovering policy lab. Retrieved from http://www.nesta.org.uk/event/labworks-2015-global-lab-gathering-london

- Kimbell, L., & Bailey, J. (2017). Prototyping and the new spirit of policymaking. CoDesign, 13(3), 214-226. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1355003

- Kootstra, G. L. (2009). The incorporation of design management in today’s business practices. Inholland University of Applied Sciences.

- Loeffler, E., & Bovaird, T. (2019). Co-commissioning of public services and outcomes in the UK: Bringing co-production into the strategic commissioning cycle. Public Money and Management, 39(4), 241-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2019.1592905

- Lykketoft, K. (2016). Designing legitimacy: The case of a government innovation lab. In C. Bason (Ed.), Design for policy (pp. 133-146). Routledge.

- Malmberg, L. (2017). Building design capability in the public sector: Expanding the horizons of development (Doctoral dissertation). Linkoping University, Linkoping, Sweden.

- May, C., & Finch, T. (2009). Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: An outline of normalization process theory. Sociology, 43(3), 535-554. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038509103208

- McGann, M., Blomkamp, E., & Lewis, J. M. (2018). The rise of public sector innovation labs: Experiments in design thinking for policy. Policy Sciences, 51, 249-267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-018-9315-7

- Mintrom, M., & Luetjens, J. (2016). Design thinking in policymaking processes: Opportunities and challenges. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 75(3), 391-402. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12211

- Mintrom, M., & Thomas, M. (2018). Improving commissioning through design thinking. Policy Design and Practice, 1(4), 310-322. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2018.1551756

- Mori, K., & Iwasaki, H. (2023). How do PSI Labs establish legitimacy?: Dynamics, approaches, and knowledge creation. In Proceedings of the IASDR conference (pp. 1-15). International Association of Societies of Design Research. https://doi.org/10.21606/iasdr.2023.160

- Mulgan, G. (2014). Design in public and social innovation: What works and what could work better. Retrieved from https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/design_in_public_and_social_innovation.pdf

- Nicolini, D. (2010). Medical innovation as a process of translation: A case from the field of telemedicine. British Journal of Management, 21(4), 1011-1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00627.x

- Palazzo, G., & Scherer, A. G. (2006). Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 66, 71-88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9044-2

- Pirinen, A., Savolainen, K., Hyysalo, S., & Mattelmäki, T. (2022). Design enters the city: Requisites and points of friction in deepening public sector design. International Journal of Design, 16(3), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.57698/v16i3.01

- Ramlau, U. H., & Melander, C. (2004). In Denmark, design tops the agenda. Design Management Review, 15(4), 48-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7169.2004.tb00182.x

- Rauth, I., Carlgren, L., & Elmquist, M. (2014). Making it happen: Legitimizing design thinking in large organizations. Design Management Journal, 9(1), 47-60. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmj.12015

- Roehrig, M. J., Schwendenwein, J., & Bushe, G. R. (2018). Amplifying change. In G. R. Bushe & R. J. Marshak (Eds.), Dialogic organization development (pp. 325-348). Berrett-Koehler.

- Shaw, P. (2002). Changing conversations in organizations: A complexity approach to change. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203402719

- Stacey, R. (2018). Understanding organizations as complex responsive processes of relating. In G. R. Bushe & R. J. Marshak (Eds.), Dialogic organization development (pp. 151-176). Berrett-Koehler.

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571-610. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9508080331

- Villa Alvarez, D. P., Auricchio, V., & Mortati, M. (2020). Design prototyping for policymaking. In Proceedings of the DRS international conference (pp. 667-685). DRS. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2020.271

- Te Aka (n.d.). Te Aka Maori dictionary. Retrieved from https://maoridictionary.co.nz/

- Van Buuren, A., Lewis, J. M., Peters, B. G., & Voorberg, W. (2020). Improving public policy and administration: Exploring the potential of design. Policy and Politics, 48(1), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557319X15579230420063

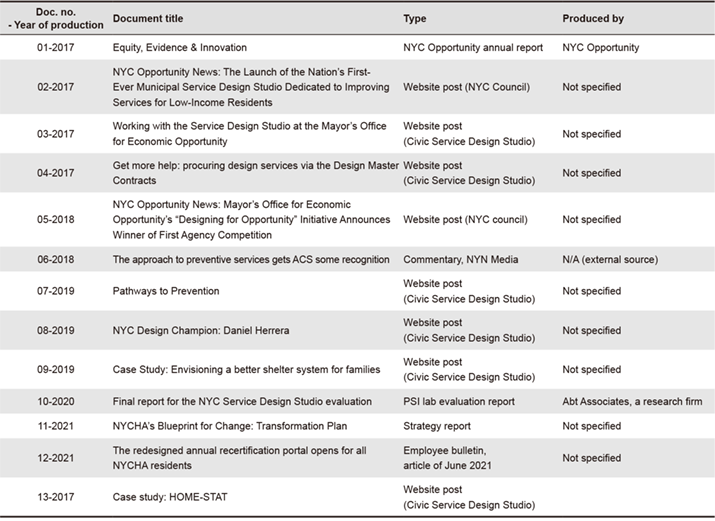

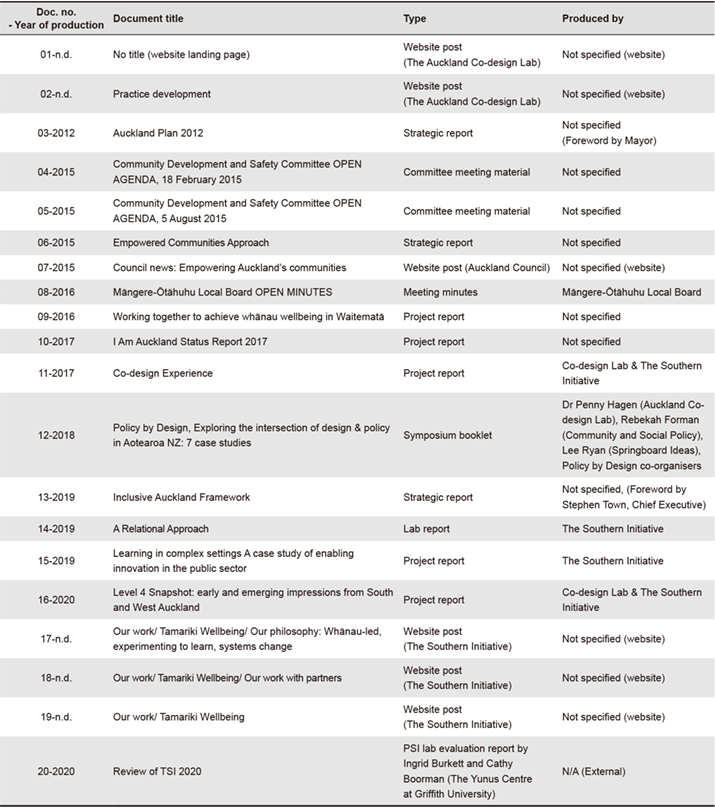

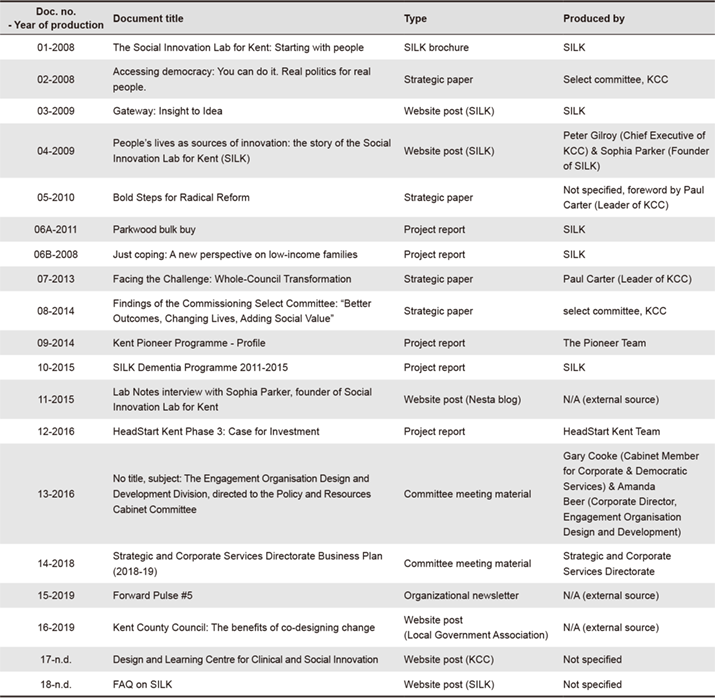

Appendix 1: List of Documents Analyzed in Each Case

Case 1: New York City government.

Case 2: Auckland City government.

Case 3: Kent County government.

Appendix 2: Codes and Themes List in Cross-Case Analysis

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1dv7seWP7TIJjbu7Xx-S3gf0wTZx0Oh-r/view?usp=sharing

*Data not relevant to the cases presented in this paper were obscured.