Public Libraries and Digital Service Development: Bridging the Gaps in Company Collaborations

Nils Ehrenberg *, Camila Hergatacorzian, and Turkka Keinonen

Aalto University, Espoo, Finland

Public libraries act as service providers for citizens, offering a wide range of services that are often procured or developed together with private and third-sector actors. This article presents a series of scenarios exploring how libraries can act together with private actors to develop new digital services. The scenarios are based on a series of interviews and workshops with libraries and private service providers in the Nordic region and show how different actors perceive the challenges of developing and maintaining digital projects in a library context. We then utilize these scenarios to discuss how to better support libraries in developing new digital services when collaborating with companies by presenting four different strategies: Strengthening the Middle-Out Position of Public Libraries, Increasing Procurement Expertise, Re-assessing Collaboration Infrastructures, and Negotiating Boundaries with Private Service Providers.

Keywords – Codesign, Collaboration, Digitalization, Libraries, Public-private Collaboration.

Relevance to Design Practice – In this article, we discuss how design practices can be used to better understand and develop new digital services in public-private collaborations in public libraries. We present strategies for improving the position of public libraries in these collaborations through a series of scenarios.

Citation: Ehrenberg, N., Hergatacorzian, C., & Keinonen, T. (2024). Public libraries and digital service development: Bridging the gaps in company collaborations. International Journal of Design, 18(3), 61-72. https://doi.org/10.57698/v18i3.05

Received March 5, 2024; Accepted November 7, 2024; Published December 31, 2024.

Copyright: © 2024 Ehrenberg, Hergatacorzian, & Keinonen. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: nils.ehrenberg@aalto.fi

Nils Ehrenberg is a postdoctoral researcher at the Aalto University Department of Design. Ehrenberg has worked in design research for 10 years in Sweden, Portugal, and Finland. Ehrenberg’s research has explored civic participation, smart home technologies, housing, and learning analytics and tools. In his research, Ehrenberg reflects on how design and technology reshape both our social relationships and our relationship to the world around us.

Camila Hergatacorzian is a doctoral student in Design with experience in interdisciplinary research projects focused on developing technologies for healthcare and education. Her current research investigates digital transformations, civic participation, and multi-stakeholder engagement in projects and services that enhance digital support for citizens.

Turkka Keinonen (Doctor of Arts 1998) has been a professor of industrial design since 2001, and is vice dean of research and innovation as well as head of doctoral education at Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture. Keinonen has worked as an industrial designer for Finnish technology industries, including shipbuilding, paper machinery, and medical equipment industries, and has been a principal research scientist at the Nokia Research Center and a visiting associate professor at the National University of Singapore. Keinonen’s publications include Mobile Usability (2003), Product Concept Design (2006), Designers, Users and Justice (2017), The Ethics of Design for User Needs (2024), and about 100 texts on user-centered design, concept design, design strategy, and ethics of user-centered design.

Introduction

In this article, we explore how public libraries build collaborations with the private sector in the context of the ongoing digitalization process of public services in Nordic countries. Nordic countries include Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland, which are culturally and socio-economically comparable regions known for their advanced welfare policies and covering public services. Nordic public services include the education and culture sector, in which the network of public libraries plays a prominent role. The Nordic region has been at the forefront of digitalization for the past decade, with high levels of digital access and a push towards further digitalization in the public sector (Eurostat, 2022). Meanwhile, this push has left many citizens on the wrong side of a so-called ‘digital divide,’ with limited or insufficient digital skills to participate in the ‘digital society.’ Public libraries, as a part of the public service offering, are no exception to this ongoing digitalization, and have long participated in facilitating this process by offering digital support and engaging in projects aimed at supporting the digital literacy of citizens (Ylipulli & Luusua, 2019). In a digital society, public libraries do not only function as knowledge repositories or support (e.g. (Christensen et al., 2022), but actively engage and develop projects and services that are aimed at improving citizen participation in a digital society (e.g. (Ylipulli et al., 2023).

As public libraries deal with the challenges brought up by society’s digital transformation, they often face the need to manage innovation or participate in more extensive networks to bring innovative solutions to these challenges. In this landscape, it is argued that facing the challenges of the digital economy can only be achieved through cross-actor, cross-sector, and cross-disciplinary interactions (Mazzucato & Ryan-Collins, 2022). Nordic public libraries are, in many ways, uniquely positioned for this work as they enjoy a certain level of independence while still part of the public infrastructure. This kind of position aligns with what is described as a ‘middle-out’ position (Cazacu et al., 2021), which gives libraries the mandate to independently engage in projects they perceive as part of their mission. As an initial exploratory study, we investigated how public libraries engage with innovation practices. In that study, we observed a gap in how private service developers and library workers perceive collaboration, with both groups expressing frustration. We also noted a lack of reports of successful projects where libraries had engaged with private service developers. This could suppose that both parties had conflicting aims, with libraries pushing toward public value creation and engaging in literacy activities for citizens, while companies leaned towards creating market value, putting business interests at the front. However, the distinction between public and market value is misguided, as public value goals can only be achieved by collaborating with the public and private sectors (Mazzucato & Ryan-Collins, 2022). We believe balanced efforts and collaboration transparency can help expose alternatives to what initially appear as conflictive. In order to further explore this issue, we initiated a series of workshops to explore how public libraries and private service developers see collaboration, how it can be imagined in the future, and what can be done to support digital literacy.

The research objective of the study presented here is to explore how libraries engage with private enterprise actors in projects related to digitalization. Therefore, we formulated our research questions as: How can we imagine future library collaborations with private enterprises to develop new digital services, and what actions are needed to support libraries in this endeavor?

The paper is structured in the following way: we introduce related work regarding public libraries and digitalization, along with the future role of libraries in a digital society, public procurement of digital services, as well as presenting a middle-out approach to public projects. We then introduce our empirical study, grounded in data collected through interviews and workshops with library workers and private industry employees as part of a broader research project. The research project aimed to explore how libraries function as platforms for civic engagement and participation in governance. Based on the empirical material, we present five scenarios based on workshops and interviews with library and private enterprise workers on how they perceive the challenges and opportunities of developing projects together. The narratives presented below are intended as potential future scenarios for how to face challenges related to digital literacy, service development, and engagement. We then combine the implications of the results with the discussion to consider how these scenarios can be used to identify four ways of strengthening the middle-out position of public libraries.

Related Work

In this paper, we contribute to the ongoing research in HCI and Design of public services on how collaborations with the private sector are developed, particularly in public libraries. We consider the current and emerging role of public libraries, draw on notions of digital and social innovation, as well as middle-out approaches (Cazacu et al., 2021; Dow et al., 2018, 2019), extending this to public management, which has been considered as a position for HCI research. Our study further includes how library practices can be seen as infrastructure civic engagement by focusing on what relations libraries enable between citizens and other sectors of society, and away from things they might provide (Kozubaev & DiSalvo, 2021).

Public Libraries in a Digital Society

For many years, public libraries have been a popular space for service designers (e.g. (Harviainen, 2014; Kozubaev & DiSalvo, 2021; Ylipulli & Luusua, 2019) to create public spaces and public service providers. Despite being perceived as offering a valuable public service, they are also often operating with limited resources that, combined with the digitalization of many of their traditional services such as books and magazines, have resulted in a perception of reduced relevance (Harviainen, 2014; Ylipulli & Luusua, 2019). Finnish public libraries have been involved in public education around technology for decades, with the promotion of digital literacy written into the Public Libraries Act that came into effect in 2017 (Public Libraries Act 2016/1492, 2017). Finns are also among the most avid library visitors in Europe while enjoying eminently high scores in their own national surveys on customer satisfaction (Quick et al., 2013; Ylipulli & Luusua, 2019). Ylipulli and Luusua (2019) argue that Public libraries play an important role in reducing digital inequality, yet the lack of long-term engagement and experience in developing projects represents an important challenge for public libraries in fully taking on this. Despite this they argue that libraries are under-utilized for engaging citizens in public innovation.

Ongoing research shows that libraries engage in developing their own services as well as with working with non-commercial interests such as volunteer-driven IT help desks (Christensen et al., 2022), partnering with universities to develop tools to facilitate citizen access to emerging technologies (Ylipulli et al., 2023), or engaging with research and design for developing co-produced events at libraries (Yoo et al., 2020). However, as observed by Ylipulli et al. (2023) engaging in this kind of development is not without challenges, as libraries may lack the resources to develop and maintain digital products. The issue of who and how digital services are provided and how they affect relational power structures in public services is also a concern in the field of digital civics, which aims to enable citizens ownership through democratic action (Vlachokyriakos et al., 2016). As the role of libraries develop, and new digital services are involved, Vlachokyriakos et al. (2016) argued for the need to connect data to place in a way that enable citizens to understand and explore, while also considering how some platforms that enable participation may limit access either through ownership (such as the sharing economy) or by requiring significant technical skill to participate.

Continuing and Enhancing the Relevance of Public Libraries

The role of public libraries has shifted with digitalization. There have been a number of moves to ensure that libraries continue to offer relevant services—such as engaging in smaller projects that connect with current concerns, digital literacy, while continuing to provide traditional library services. The shifting role of public libraries has attracted the attention of researchers engaged in digital civics and HCI, arguing that libraries represent a valuable public space beyond their role as knowledge repositories (Kozubaev & DiSalvo, 2021; Ylipulli & Luusua, 2019). While public libraries have responded to digitalization by providing digital alternatives to their traditional services in the form of remote loaning, e-books, audio books, etc., there is a concern that the library and the work of librarians have become less visible, threatening the library’s role as a public space (Chowdhury et al., 2006; Harviainen, 2014; Kozubaev & DiSalvo, 2021). This has resulted in calls for re-inventing the library beyond its role as a knowledge repository (Chowdhury et al., 2006), and for taking on a more active role in supporting digitalization and technical literacy (Serholt et al., 2018), as well as calls for making the invisible work of the library more visible (Harviainen, 2014). Kozubaev and DiSalvo (Kozubaev & DiSalvo, 2021) argued that one of the ways to work with this concern is through relational agency, i.e., work to make the digital interactions meaningful and connect them to existing interactions and relations. While libraries do engage in these practices, the available tools are often either not designed for library purposes or come with commercial interests that may not align with the aims of the library (Yoo et al., 2020).

Procuring Conceptual Design for Public Services

In Finland, procurement is determined by the Act on Public Procurement (Act on Public Procurement and Concession Contracts, 2018), which implements European Parliament directives for public procurement. The Act on Public Procurement is intended to enhance the effectiveness in use of public funds, as well as ensuring expedient procurement processes that enable small and medium-sized enterprises to have equal access to participate in tenders. The notion of the private sector as a public sector provider emerges from the idea that private sector services are more successful because of their cost-effectiveness, faster performance, and higher quality (McCue et al., 2015). Procurement systems are expected to remain transparent, ensure good management of public funds, prevent risks of integrity in the process, and maintain accountability and control (OECD, 2009). However, governments face multiple grand challenges, such as digital transformation, climate change, and aging populations that often require them to value other criteria on top of those mentioned above. In such cases, some argue in favor of Public Procurement for Innovation instead of buying off-the-shelf products (Edquist & Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, 2012).

Uyarra et al. (2014) identified a range of challenges to public service innovation in a study based on a survey supplied to public service organizations in the United Kingdom. The challenges included risk management, management of intellectual property rights, poor capability of procurers, the scale and scope of contracts, lack of interaction with procuring organizations, too prescriptive specifications, and lack of demand for innovation. In particular, Uyarra et al. (2014) noted that small companies perceive themselves as disadvantaged in part because of the size of contracts, but also due to lack of feedback in the procurement process. Akin to this, Park-Lee (2020) noticed how lack of communication during the procuring process of service design in Finland prevented design consultancies from understanding the goal and scope of the tender. Design is progressively making its way into government activities with the aim of facilitating innovation, with design consultancies playing a significant role. Limited design proficiency in the public sector can contribute to situations where the design expertise is under-utilized, and where the correspondence between the value and scope of the tender and the workload required is lacking (Park-Lee & Person, 2018).

Government purchasing professionals are therefore faced with the challenge of being able to lean towards more flexible (and cost-effective) criteria while maintaining the integrity of the process (McCue et al., 2015; Mikalsen & Farshchian, 2020). In recent years there have been attempts at resolving some of the challenges in public innovation through restructuring the procurement process, such as better engaging with end-users (Torvinen & Ulkuniemi, 2016) or utilizing hackathons, which may allow for better mutual learning between government actors and companies, if they have the right participants (Pihlajamaa & Merisalo, 2021).

Challenges on how to drive innovation in collaborative networks are found beyond financial mechanisms of procurement. One of the main challenges to collaborative networks concerns how to balance the role of different stakeholders. Issues regarding the level of stakeholder participation has long been a part of participatory design discourse, with calls for more bottom-up approaches as well as concerns that these approaches are difficult to scale. Public libraries in the Nordics are uniquely positioned as operating with relative independence, while also part of the larger regional governance, we therefore turn towards a middle-out approach and in-between infrastructures as a way for public libraries to engage in public innovation.

A Middle-Out Approach to Public Projects

There has been a growing interest among researchers to engage with design for civics or digital civics, and DiSalvo et al. (2014), building on the work of Latour (2005), suggested that design can be used to articulate matters of concern, that is engaging with complicated issues by considering the networks of actors and relationships that design acts upon. Botero and Saad-Sulonen (2010) found that tools that facilitate conversation between citizens and public officials require engagement, commitment, and support from all involved stakeholders. As HCI has further engaged with digital civics, there have been calls to step away from what is perceived as an either top-down or bottoms-up approach to technology, and instead facilitating engagements between different stakeholders in what has been called a middle-out approach (Cazacu et al., 2021). Dow et al. (2018, 2019) argued that in their work on Local Offer, a platform for services for people with special needs and disabilities, a major challenge was negotiating between grass-roots proposals and policy-driven bureaucrats. Dow et al. (2018, 2019) perceived that in the Local Offer project, most of the work was being done in the middle-out, as it allowed for drawing on the collective knowledge of all the participants in the project.

The process of drawing on collective knowledge requires a continuous alignment of conflicting views (Cazacu et al., 2021). Design has been borrowing from Star’s conceptualization of infrastructures, established as a set of technical, social, and organizational arrangements that lead to specific and ongoing negotiated order of things, this could include technologies, standards, policies and more (Karasti et al., 2010; Star, 1999; Star & Ruhleder, 1996). Drawing from this, infrastructuring suggests taking a relational approach, rather than looking at things, which focuses on what these things enable. The use of infrastructure in its verb form “infrastructuring” is therefore continuously ongoing, and acts in opposition to working in projects which have a limited timeframe (Björgvinsson et al., 2012; Karasti et al., 2010). With a focus on considering long-term and continuous engagement, infrastructuring has been adopted as a way to engage in collaborations in participatory design practices (Karasti, 2014; Karasti et al., 2010). The notion of infrastructuring has attracted some interest among researchers studying public spaces as well as libraries (Kozubaev & DiSalvo, 2021). Public libraries take on the role of social infrastructures as they function as meeting points for civic engagement, social inclusion, as well as empower citizens through technology and digital literacy (Hodgetts et al., 2008; Klinenberg, 2018). The role of libraries as social infrastructures has also led to the critique of how libraries function as infrastructures that reinforce existing power structures (Drabinski, 2019), making it important to consider how these infrastructures are developed. Ylipulli et al. (2023) noticed how libraries emphasize bottom-up innovation and experimentation, while there is little attention to how innovation is managed and how it can be infrastructured.

The role of public libraries has been challenged with digitalization and new ways to access information, and concerns that online or digital services may limit the role public libraries play as a public space. However, there have been calls among researchers for libraries to instead take on a more active role in supporting citizens in digitalization, and public libraries in the Nordics have responded to this by offering support, such as IT Help desks, for citizens struggling with the digital transition. We have also observed that there are tensions when public institutions such as libraries collaborate with private companies, indicating that the structure of public procurement, especially when working with design which involves more exploratory processes, makes it difficult to drive innovation projects that involve both public and private stakeholders. As Nordic libraries are often able to act with a certain independence, while remaining a part of public infrastructures, we have presented research arguing for a middle-out approach to innovation in public libraries. Our research objective is therefore to explore the challenges of public libraries when engaging in innovation processes with private companies, and how to strengthen the position of public libraries in these projects.

Methods

This research was conducted as part of a larger project which investigated how to increase user involvement in the development of public e-services. The project studied how user involvement can be integrated into existing library facilities. During an exploratory interview study in the early stages of the project, the participants brought up issues in the collaboration between libraries and private sector tech and e-service providers. To follow up on these issues, we decided to initiate a dialogue between both parties, explore how they experienced previous collaborations and how they imagined they could be in the near future. As discussed in the related work section, design has been utilized in the public sector activities for accompanying joint processes or facilitating multi-stakeholder discussions, in many occasions, by building strategic scenarios (Hyysalo et al., 2023). We embraced this typology of design in the public sector and invited librarians, managers, and designers in private companies to engage with us in a dialogue about future ways of collaborating.

This study utilized two sets of data, the first set was composed by the interviews that brought up the issue in a previous stage, and the second set of data includes results of workshops generated with the aim of discussing library-company collaborations. From these datasets, we developed a series of scenarios to unify our interview and workshop participants, i.e., the librarians’, managers’, and designers’ views on desirable collaborations. While scenarios can be used for anticipating design choices when the “time horizon of the project is shifted significantly forward” (Celi, 2010), they can also be used for understanding and catalyzing how different stakeholders can collaborate (Abou Amsha et al., 2023) and reframe present situations (Wilkinson, 2017).

Data Collection

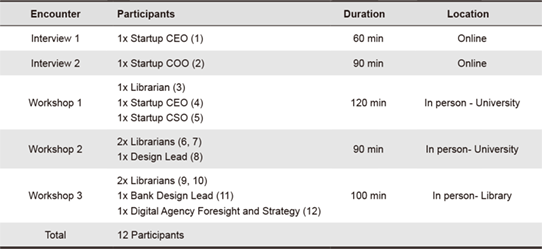

The study was conducted over a period of 6 months in Finland’s capital region. We started the recruitment process by listing potential participants from the private sector who had prior experience working with libraries, and libraries that we knew had carried out collaborative projects with the private sector, universities, or worked with digital support. According to the services libraries provide, we identified some categories of companies as potential collaborators which included extended reality, design consulting, and private e-service providers. Thus, in addition to having prior experience with libraries, companies had to be part of one of the three categories. We reached out to a series of local companies and libraries, contacting one or two employees from each. We recruited a total of twelve participants; Table 1 provides details about their roles and the data collected in the process, as well as the specifications for each encounter.

Table 1. Methods and Participants

We conducted a qualitative study using two methods for data collection: workshops and semi-structured interviews. The workshops were our main source of data gathered from the participants, while the interviews served as rich complementary material. In the interviews we explored participants’ previous experiences and their perception of what had made those experiences positive or negative. During the interviews, participants often presented barriers to collaboration as well misconceptions about how the other party would participate in these projects. The interviews were run first as part of an earlier stage of the project; they were conducted online using a semi-structured guide of questions.

Regarding the workshops, we organized one per company resulting in a total of three workshops together with: an IT company, a design consultancy, and a bank. With the workshops, our aim was to allow the participants to reflect on previous experiences and build narratives that would inform scenarios for near future collaborations. During the workshops, the dialogue format served to unveil opportunities and commonalities where participants representing public and private interests shared similar aims and goals for delivering useful services. Each workshop followed a similar dynamic, whereby in the first half, we used some questions to prompt each participant to briefly tell how they engage with users, and then the commonalities and differences on their strategies were later discussed. In this initial discussion, we also touched on their past collaborative experiences. During the second half, the participants first individually characterized possible scenarios for collaborating and running projects together using post-it; and later shared their notes in a round table discussion. This collaborative process led to negotiating both parties’ values. In a final workshop we decided to include participants from the public sector National Digital and Population Agency as they orchestrate government digital strategy between private, public, and third sector actors. The workshops and interviews were carried out in English. They were video/audio recorded for later transcription. The data was collected and handled in accordance with the national guidelines for ethical principles in research (Tutkimuseettinen Neuvottelukunta (TENK), n.d.).

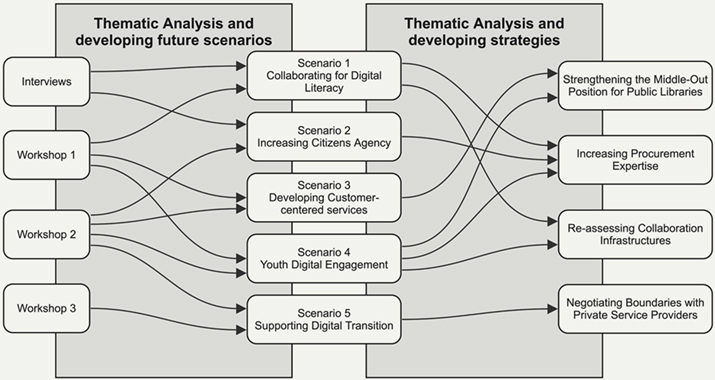

Analysis: Coding and scenarios

Data from the interviews and workshops was qualitatively analyzed through two rounds of thematic coding and analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). After collecting the data, we transcribed all the interviews and the workshops and coded the transcripts using Atlas.ti. While refining the codes, the research team discussed the findings. First, we defined three groups that would help to organize the codes and future themes into three consecutive phases of how projects are carried out in libraries (initiative, control and ownership).

Organizing the codes in chronological order helped us to situate the content of the interviews in a scenario narrative as well as the role each stakeholder took. The scenarios offer descriptions of stakeholders’ roles in each of the phases. Scenarios have been used in design to “describe the use of a future system” (Rosson & Carroll, 2002). They portray an understanding of what could result in the successful accomplishment of shared goals (Nielsen, 2004). In our case, we chose to use a neutral tone of voice that would reflect the positive aspects of collaborating as well as the struggles. The scenarios are based on real experiences that the participants narrated that were anonymized and synthetized, putting emphasis on the challenges they faced because of the cross-sector collaboration. We wrote the narratives and used illustrations and diagrams to support sharing the results of the workshops with participants. By using visualization and materiality to support sharing and communication among different stakeholders (Hines & Zindato, 2016; Selin et al., 2015), we reinforce what has been discussed as one of the prominent design typologies in the public sector (Hyysalo et al., 2023). In the end, we shared the scenarios with the participants who gave positive feedback and requested minor changes as further anonymization of one of the cases. However, we did not collect data on how the scenarios circulated within the organizations. Finally, by looking further at the codes and scenarios, we arrived at the themes that will be presented in the discussion.

Figure 1. How the data informed scenarios and final strategies.

Results

The shared elements within our participants’ experiences in managing collaborative projects between public libraries and private companies revealed an elemental framework. Furthermore, collaboration between libraries and companies could be split into three groups that represent the phases of collaborative projects: Initiative, Control, and Ownership. In the following, we present a series of scenarios that catalyze the themes of our findings in these three stages of how collaborative projects with the private sector can be run in public libraries.

Scenarios

We constructed a series of 5 scenarios, drawing from both the past narratives recalled by workshop and interview participants, and future narratives developed by workshop participants. These scenarios portray desirable collaborations in which problems and common goals become evident. The assumptions we used for defining each scenario were categorized in shared motivations and initiative (for the group Initiative), control (for the group Control) and ownership and maintenance (for the group Ownership).

Scenario (S1): Collaborating for Digital Literacy

Figure 2. Illustration of scenario “Collaborating for Digital Literacy”. Designed by one of the authors.

Finnish libraries host various events, including Finnish language cafés, organized by librarians. One library has been using new ICTs for the cafés and is considering including them further. They receive a small budget from the city to run their own project. This is an opportunity to collaborate with local small or medium Enterprises specialized in creating new ICT solutions.

One company offers different types of software they have already developed and provides training for librarians on their use. Librarians who initially doubted incorporating new technology into the language cafés agreed to participate in the training sessions. They received training and, in collaboration with the company, developed an educational guide for introducing the new software into the language cafés.

The project has been running successfully, and other libraries want to implement it. They contacted the same company to replicate the training process in other libraries. This initiative allowed librarians to explore new dimensions of literacy, blending language with technology. The company strengthened its relationship with a public client and executed a project in line with its vision of creating socially relevant software.

Scenario (S2): Increasing Citizen Agency

Figure 3. Illustration of scenario “Increasing Citizen Agency”. Designed by one of the authors with elements form Green at The Forebury by Thomas Nugent, Green at The Forebury - geograph.org.uk - 1962495, CC BY-SA 2.0.

The City of Espoo partnered with an urban planning studio to explore opportunities for redesigning public spaces within the municipality. As the city aims to involve citizens more directly in the decision-making processes, they began planning how to strengthen the project.

They came up with the idea of organizing workshops at schools and libraries for people to participate in the process of designing the city. They utilized several technologies that facilitate citizens’ abilities to model the city. In schools, they were supported by teachers, and in libraries, by librarians. This means that, before launching the new project, they needed to conduct a few training sessions with them on how to use the technology.

After the workshop ended, the results were showcased in the local art museum and reported to the city authorities. Company X and the City of Espoo gained valuable input and ideas, and librarians increased their ability to use new technologies that they can incorporate into their practices.

Scenario (S3): Developing Customer-centered Services

Figure 4. Illustration of scenario “Developing Customer-centered Services”.

Designed by one of the authors with elements from @upklyak on Freepik.

The Helsinki Library Network is managed by the City of Helsinki Municipality. The municipality decided that the library’s computers could use a unified facade for their operating system. They opened a public call for IT consultancies to propose their strategies and budgets for addressing this issue. After a few months, they hired a well-known company with experience working with libraries.

The company began its research by visiting many libraries across Helsinki to shadow customers and interview librarians. The company started by developing a low-fi prototype and conducted a small pilot in one of the libraries, with the purpose of gradually scaling up the system. As they built the system in modules, with every new iteration, they could add or remove features depending on each library’s needs.

The project concluded, and the consultancy delivered the customizable software solution, along with a report containing recommendations for further improvement. The OS facade was unified, and both librarians and citizens reported a sense of ownership of the system.

Scenario (S4): Youth Digital Engagement

Figure 5. Illustration of scenario “Youth Digital Engagement”.

Designed by one of the authors with elements form upklyak on Freepik.

The City of Helsinki has allocated a new budget for libraries, giving them the freedom to use it as they wish. Young librarians from a small library are currently engaged in improving their approach to handling younger users who occasionally misbehave. They came up with the idea of purchasing new technology and reached out to a small company. The company has prior experience as they work with programmable robots at local public schools, so they signed a contract with them.

The deal includes the technology itself, its maintenance, and training sessions for librarians and library users. Once they started using the robots, everyone became very excited about them. Some of the older teenagers, who used to be disruptive, adopted leadership roles after participating in the training sessions and are now eager to teach newcomers how to use the robots.

In an attempt to scale up the project within the entire library network, librarians from larger libraries commented that implementing such a project would be impossible due to the higher daily influx of children, making it unmanageable. Despite the project being hard to scale in larger libraries, it has become a flagship initiative for smaller libraries on how to run innovative projects.

Scenario (S5): Supporting Digital Transition

Figure 6. Illustration of scenario “Supporting Digital Transition”. Designed by one of the authors.

Both private and public e-service providers are increasingly transitioning to digital platforms and closing their physical branches. As a result, citizens are turning to libraries for help. It is the library’s duty to help citizens in enhancing their digital skills, however librarians don’t have formal training on how to offer support for using public and private e-services. Furthermore, it is against library policy for the librarians to handle the personal data of citizens.

In an attempt to solve this issue, municipal authorities established a special working group involving all essential e-service providers to address this concern. The group is co-organized by the DVV (National Digital and Population Agency) digital support team and a volunteer-based NGO. They initiate a co-design process in which they engage e-service providers, libraries, and citizens, particularly those affected by digital transformation, such as seniors.

The group comes up with a series of experiments to try out in order to support a more equitable digitalization transition. The experiments enact different settings on how both private and public service providers’ presence in libraries could be enhanced. They need to figure out how it could be done in a non-disruptive manner so libraries can continue to serve as free public spaces. The aim is for librarians to be able to dedicate more time to other responsibilities, and citizens have guaranteed access to secure digital support.

Discussion

In the scenarios we have presented five ways in which public libraries can work to support digital literacy and civic engagement, as part of the digital transition. In some of the scenarios, library workers act as clients contracting work from the private sector, while in others it is a matter of shared agendas. It is in the interest of many companies (such as banks) that the digital literacy of the public improves as they will be more reliable customers that way. This shared agenda, despite the end-goals being different, can be considered an enabler for collaboration. We also note that in these projects, control over the process and ownership of the end product is something that needs to be paid close attention to. As noted by e.g. (Serholt et al., 2018), digitalization opens up opportunities for public libraries to engage in digital civics, yet, as also observed by Ylipulli et al. (2023) this can be challenging. We therefore consider how the scenarios developed as part of this research can be used to identify four strategies for libraries to continue to act as spaces for innovating and supporting digitalization in public services.

While the workshops explored how the participants engaged in design practice, the participants in the study, both from companies and public libraries, did not express a need for design organizations, such as universities or design agencies, to provide continuous facilitation in the scenario process, as these organizations already possess sufficient or even advanced design competencies and were confident that these would be adequate for managing collaborations. Furthermore, the way these collaborations were discussed indicated that they would utilize co-design methods and practices in potential collaborations. However, as researchers we did perceive that the participants appreciated the workshops as they initiated conversations and helped them find common interests, indicating that design institutions could take a role of initiating follow-up actions and initiating new projects with the participants.

Strengthening the Middle-Out Position for Public Libraries

While some form of middle-out position can be seen as inherent to the positioning of public libraries in the Nordic region, it is dependent on their independence. One aspect that came out of the workshops and the scenarios (S3, S4), is that public libraries in the Nordic countries are used to a certain degree of independence. The library workers perceive that this independence is important as it allows them to engage with the citizens when developing new services, and one of them expressed “we still have that independence in the grassroots like what we do daily. We can decide ourselves and have new ideas ourselves and incorporate them so yes, that’s a great thing” (participant 3). However, this independence is being encroached upon with the development of larger ICT infrastructures that make it easier to connect and manage multiple sites through centralized procurement. While this centralizing process has benefits in terms of ensuring same or similar service and potentially reduced costs, it also conflicts with the libraries tradition of independence. One library worker expressed that “for now I think [the city] is moving in a more centralized and closed system where we don’t necessarily get any input or any info on anything that’s happening or any new stuff that’s coming. Until it drops on us and then we just have to figure it out” (participant 7). Dow et al. (2018) argued that larger agendas in the city to increase grassroots innovation coexist with top-down centralized initiatives to drive cost-efficiency. Librarians occupy a similar position, where they are sometimes able to act outside of the rigorous processes of the local and regional governments, allowing them to innovate new services for the public, often through the use of design-related practices. Thus, to strengthen the libraries position in middle-out processes and supporting their ability to innovate, a certain degree of independence is needed. It might not be the most efficient solution short-term, but it may be necessary if libraries are to be able to innovate and prototype new public services.

Increasing Procurement Expertise

Many larger organizations have specialized procurement expertise, while in public libraries this task appears to only have two paths: it is either left to the various library workers who have to engage with external clients without having the support or training for public procurement; or it is handled in a centralized manner by the city administration. These alternatives are portrayed in several of the scenarios (S1, S2, S4), where it became clear that procurement is one of the challenges for libraries when managing innovation. While the libraries have the mandate to innovate, actual procurement is perceived as complicated with both private service developers and library workers expressing uncertainty or frustration. One service developer perceived the libraries as lacking the expertise for public procurement, expressing that “They say the procurement law forbids us from doing X, Y, and Z. It doesn’t, they don’t just understand the law.” Another service developer (participant 2) expressed that “So, to address specific needs that libraries have, they need to set up innovative public procurement systems (...)” “Maybe that’s another way, this innovative public procurement which I mentioned, in this hackathon context, maybe.” Hence, it became clear that from the companies’ perspective, librarians’ lack of expertise in procurement works against leaning towards more flexible processes that allow innovation, as they feel pressured by maintaining the integrity of the process (McCue et al., 2015; Mikalsen & Farshchian, 2020). Engaging in more innovative procurement practices might be a way forward as one library worker (participant 6) expressed, “...I think is the challenges of actually telling what we want, what we need, to an outside developer or firm”, suggesting that there is a need for libraries to improve their procurement expertise but also that in digital projects they are often uncertain at exactly what they need when they initiate a project. The lack of professional knowledge on the field being procured is a concern in design literature as it can lead to miss-assessing the expertise of the companies (Park-Lee & Person, 2018). For libraries to operate as service innovators they therefore need resources to improve their ability to negotiate and engage with private service developers. As in the scenarios S1 and S4, allocating a small budget for libraries to independently initiate projects can strengthen the middle-out role and allow them to take small risks and train their procurement expertise.

Reassessing Collaboration Infrastructures

While libraries need to improve their expertise in engaging with companies, in several of the discussions it also became clear that it is sometimes difficult for companies to engage with the public sector. Many of the projects are enabled by applied development funding. For smaller companies engaging with application processes can be expensive as there is no way of knowing whether the application is successful (Uyarra et al., 2014). One participant (participant 5) from a small design agency added, “it sometimes takes a lot of money for us, time for us to commit and help with the application.” There is therefore not only a need for better procurement expertise in libraries, but also to develop practices and infrastructures that allow libraries to contract and set up collaborations with appropriate companies without requiring companies to engage in long procurement processes without knowing if they will be able to secure the contract. In both the scenarios S4 and S1 the discussion was partially centered on a desire to work with smaller companies with an existing engagement in the topic, without clearly knowing what the end result was going to be. However, it is not only a matter of simpler procurement practices, but also maintenance and ownership of the outcome. When the project ends, the maintenance often falls on the library which lacks the resources and expertise. One company contends that if they were to share ownership and be able to use the material in other contexts, they would be interested in engaging with maintenance. However, such a solution would also shift the boundaries of public and private in digital services.

Negotiating Boundaries with Private Service Providers

While we have discussed the need for a strengthened middle-out position, with improved procurement expertise and better innovation infrastructure for libraries—there is also a need to more clearly negotiate boundaries (S5). Libraries are accountable for supporting and developing digital skills among citizens, not offering support for commercial services. While this might appear self-evident, it is also difficult to reject visitors who need help. The boundaries can also be opaque, as some technologies are difficult to separate from general support, and a customer looking for support with a service might end up at the library first as one library worker (participant 10) said, “they might say that we only have computers, but there is an implication that we also help because we are sort of first contact point for digital guidance. ”To both libraries and companies this kind of support is also a security concern, and another library worker (participant 10) stated that “technically speaking we do not have the legal protections to go to someone’s personal like information. There are situations where we have to ask for their consent (...) we often work in legal gray spaces (...) especially when it comes to banking, social services, etc. etc.” While offering support for public services is perceived as somewhat acceptable as they are all funded by tax money, there is a growing resentment that they are being exploited by companies not wanting to offer support, with one library worker (participant 6) stating that “And I think it’s funny that they are a very like is there anything more commercial or capitalist than a bank and they are using a free space in a library now and then to give their customers help how to use their services and mostly they are letting us do it basically for free.” In between taxpayers demands and the lack of accountability of private service providers, librarians are in the middle of blurry boundaries between a profit-driven private sector and public spaces (Kozubaev & DiSalvo, 2021). Therefore, without having more clearly negotiated boundaries with private service developers it is difficult to build better relations for innovation with private companies.

Conclusions

In this article we have explored how to strengthen the middle-out position of public libraries in collaborations with the private sector in the context of the Nordic region. While it may be tempting to generalize our results to other regions, we believe one should do so carefully, as the strong position of public libraries combined with a broad belief in collaborative design is a part of the unique cultural context in which this research is positioned. However, we believe that many of the challenges we have identified are likely to occur in other contexts and our results can therefore be used to formulate research questions or develop hypothesis in other public-private collaboration studies and initiatives. We have presented a series of scenarios, based on which we have made four calls to action that are needed in order for libraries to develop stronger and more successful collaborations with the private sector, while maintaining library independence to strengthen their middle-out position and release some of the tension that librarians deal with being stuck in the middle of citizens and municipal agendas. Improving the expertise in public procurement and engaging with innovative procurement processes increases librarians’ capabilities to better utilize the resources that companies can provide. We call for reassessing the collaboration infrastructures, ensuring that both libraries and private service developers have a better understanding of how to engage with each other for initiating common projects and share ownership to improve integration and maintenance. And finally, the need for more clearly negotiated boundaries in terms of what kind of services libraries offer and how the private sector could take accountability for shifting the burden of support of these services to the public.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge our partners in the CAPE project. This research was funded by Nordforsk Grant Number: 98907. We would also like to thank the Oodi Library for supporting and assisting us in conducting our research.

References

- Abou Amsha, K., Grönvall, E., & Saad-Sulonen, J. (2023). Emergent collaborations outside of organizational frameworks: Exploring relevant concepts. In Proceedings of the 11th international conference on communities and technologies (pp. 163-173). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3593743.3593778

- Act on Public Procurement and Concession Contracts, 1397/2016 (2018). https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/2016/en20161397.pdf

- Björgvinsson, E., Ehn, P., & Hillgren, P.-A. (2012). Agonistic participatory design: Working with marginalised social movements. International Journal of Cocreation in Design and the Arts, 8(2-3), 127-144. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2012.672577

- Botero, A., & Saad-Sulonen, J. (2010). Enhancing citizenship: The role of in-between infrastructures. In Proceedings of the 11th biennial participatory design conference (pp. 81-90). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1900441.1900453

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cazacu, S., Hansen, N. B., & Schouten, B. (2021). Empowerment approaches in digital civics. In Proceedings of the 32nd Australian conference on human-computer interaction (pp. 692-699). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3441000.3441069

- Celi, M. (2010). Part I: Introduction, theorical aspects, interpretative keys. In Advanced design cultures: Long-term perspective and continuous innovation. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08602-6

- Chowdhury, G., Poulter, A., & McMenemy, D. (2006). Public library 2.0: Towards a new mission for public libraries as a “network of community knowledge.” Online Information Review, 30(4), 454-460. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684520610686328

- Christensen, C., Ehrenberg, N., Christiansson, J., Grönvall, E., Saad-Sulonen, J., & Keinonen, T. (2022). Volunteer-based IT helpdesks as ambiguous quasi-public services—A case study from two Nordic countries. In Proceedings of the Nordic human-computer interaction conference (Article 44). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3546155.3546660

- DiSalvo, C., Lukens, J., Lodato, T., Jenkins, T., & Kim, T. (2014). Making public things: How HCI design can express matters of concern. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 2397-2406). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557359

- Dow, A., Comber, R., & Vines, J. (2018). Between grassroots and the hierarchy: Lessons learned from the design of a public services directory. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (Article 442). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3174016

- Dow, A., Comber, R., & Vines, J. (2019). Communities to the left of me, bureaucrats to the right…here I am, stuck in the middle. Interactions, 26(5), 26-33. https://doi.org/10.1145/3351735

- Drabinski, E. (2019). What is critical about critical librarianship? Art Libraries Journal, 44(2), 49-57. https://doi.org/10.1017/alj.2019.3

- Edquist, C., & Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J. M. (2012). Public procurement for innovation as mission-oriented innovation policy. Research Policy, 41(10), 1757-1769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.04.022

- Eurostat. (2022, March 30). How many citizens had basic digital skills in 2021? https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20220330-1

- Harviainen, J. T. (2014). Service multipliers, service visibility. Design Management Review, 25(2), 28-33. https://doi.org/10.1111/drev.10279

- Hines, A., & Zindato, D. (2016). Designing foresight and foresighting design: Opportunities for learning and collaboration via scenarios. World Futures Review, 8(4), 180-192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1946756716672477

- Hodgetts, D., Stolte, O., Chamberlain, K., Radley, A., Nikora, L., Nabalarua, E., & Groot, S. (2008). A trip to the library: Homelessness and social inclusion. Social & Cultural Geography, 9(8), 933-953. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360802441432

- Hyysalo, S., Savolainen, K., Pirinen, A., Mattelmäki, T., Hietanen, P., & Virta, M. (2023). Design types in diversified city administration: The case City of Helsinki. The Design Journal, 26(3), 380-398. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2023.2181886

- Karasti, H. (2014). Infrastructuring in participatory design. In Proceedings of the 13th participatory design conference (pp. 141-150). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2661435.2661450

- Karasti, H., Baker, K. S., & Millerand, F. (2010). Infrastructure time: Long-term matters in collaborative development. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 19(3-4), 377-415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-010-9113-z

- Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the people: How social infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civic life (1st ed.). Crown.

- Kozubaev, S., & DiSalvo, C. (2021). Cracking public space open: Design for public librarians. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (Article 627). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445730

- Latour, B. (2005). From realpolitik to dingpolitik. In P. Weibel & B. Latour (Eds.), Making things public: Atmospheres of democracy (pp. 14-44). MIT Press.

- Mazzucato, M., & Ryan-Collins, J. (2022). Putting value creation back into “public value”: From market-fixing to market-shaping. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 25(4), 345-360. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2022.2053537

- McCue, C. P., Prier, E., & Swanson, D. (2015). Five dilemmas in public procurement. Journal of Public Procurement, 15(2), 177-207. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-15-02-2015-B003

- Mikalsen, M., & Farshchian, B. (2020, June 15). Can the public sector and vendors digitally transform? A case from innovative public procurement. In Proceedings of the 28th European conference on information systems (Article 62). https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2020_rip/62

- Nielsen, L. (2004). Engaging personas and narrative scenarios. Copenhagen Business School.

- OECD. (2009). OECD principles for integrity in public procurement. https://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/48994520.pdf

- Park-Lee, S. (2020). Contexts of briefing for service design procurements in the Finnish public sector. Design Studies, 69, Article 100945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2020.05.002

- Park-Lee, S., & Person, O. (2018). Perspective: The gist of public tender for service design. In Proceedings of the DRS biennial conference series (pp. 25-28). DRS. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2018.367

- Pihlajamaa, M., & Merisalo, M. (2021). Organizing innovation contests for public procurement of innovation – A case study of smart city hackathons in Tampere, Finland. European Planning Studies, 29(10), 1906-1924. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1894097

- Public Libraries Act 2016/1492, 1492 (2017). https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/2016/en20161492.pdf

- Quick, S., Prior, G., Toombs, B., Taylor, L., & Currenti, R. (2013). Cross-European survey to measure users’ perceptions of the benefits of ICT in public libraries. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

- Rosson, M. B., & Carroll, J. M. (2002). Scenario-based design. In Human computer interaction handbook (pp. 1032-1050). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/b11963-ch-48/scenario-based-design-mary-beth-rosson-john-carroll

- Selin, C., Kimbell, L., Ramirez, R., & Yasser, B. (2015). Scenarios and design: Scoping the dialogue space. Futures, 74, 4-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2015.06.002

- Serholt, S., Eriksson, E., Dalsgaard, P., Bats, R., & Ducros, A. (2018). Opportunities and challenges for technology development and adoption in public libraries. In Proceedings of the 10th Nordic conference on human-computer interaction (pp. 311-322). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3240167.3240198

- Star, S. L. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist, 43(3), 377-391. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955326

- Star, S. L., & Ruhleder, K. (1996). Steps toward an ecology of infrastructure: Design and access for large information spaces. Information Systems Research, 7(1), 111-134. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.7.1.111

- Torvinen, H., & Ulkuniemi, P. (2016). End-user engagement within innovative public procurement practices: A case study on public–private partnership procurement. Industrial Marketing Management, 58, 58-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.05.015

- Tutkimuseettinen Neuvottelukunta (TENK). (n.d.). Ethical review in human sciences. Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK. Retrieved 17 November 2023, from https://tenk.fi/en/ethical-review/ethical-review-human-sciences

- Uyarra, E., Edler, J., Garcia-Estevez, J., Georghiou, L., & Yeow, J. (2014). Barriers to innovation through public procurement: A supplier perspective. Technovation, 34(10), 631-645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2014.04.003

- Vlachokyriakos, V., Crivellaro, C., Le Dantec, C. A., Gordon, E., Wright, P., & Olivier, P. (2016). Digital civics: Citizen empowerment with and through technology. In Extended abstracts of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1096-1099). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2851581.2886436

- Wilkinson, A. (2017). Strategic foresight primer. European Political Strategy Center.

- Ylipulli, J., & Luusua, A. (2019). Without libraries what have we? Public libraries as nodes for technological empowerment in the era of smart cities, AI and big data. In Proceedings of the 9th international conference on communities & technologies (pp. 92-101). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3328320.3328387

- Ylipulli, J., Pouke, M., Ehrenberg, N., & Keinonen, T. (2023). Public libraries as a partner in digital innovation project: Designing a virtual reality experience to support digital literacy. Future Generation Computer Systems, 149, 594-605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2023.08.001

- Yoo, D., Tabard, A., Ducros, A., Dalsgaard, P., Klokmose, C. N., Eriksson, E., & Serholt, S. (2020). Computational alternatives vignettes for place- and activity-centered digital services in public libraries. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1-12). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376597