The Empathic Co-Design Canvas: A Tool for Supporting Multi-Stakeholder Co-Design Processes

Wina Smeenk

Inholland University of Applied Sciences, Diemen, The Netherlands

Wiens ontwerperschap, Broek in Waterland, The Netherlands

The numerous grand challenges around us demand new approaches to build alternative sustainable futures collectively. Whereas these so-called co-design processes are becoming more mainstream, many multi-stakeholder coalitions lack practical guidance in these dynamic and systemic challenges based on entangled relationships, interactions, and experiences between stakeholders and their environments. Although scholars and practitioners convey a lot of co-design theories and methods, there does not seem to be a practical instrument beyond methods that supports new coalitions with an overview of a co-design process to come and in making shared and fundamental co-design decisions. Therefore, this paper proposes the empathic Co-Design Canvas as a new intermediate-level knowledge product existing of eight co-design decision cards, which together make up the Canvas as a whole. The Canvas is based on an existing theoretical framework defined by Lee et al. (2018), an empirical case study, and a diversity of experiences in education and practice. It aims at supporting multi-stakeholder coalitions to flexibly plan, conduct, and evaluate a co-design process. Moreover, the Canvas encourages coalitions to not only discuss the problematic context, a common purpose, envisioned impact, concrete results, and each other’s interests and knowledge, but also power, which can create trust, a more equal level playing field and empathy, and help manage expectations, which is greatly needed to overcome today’s grand challenges.

Keywords – Systemic Co-design, Empathic Design, Intermediate-level Knowledge, Multi-stakeholder Coalitions, Power, Societal Impact.

Relevance to Design Practice – The paper contributes an easy-to-use instrument beyond methods to the landscape of co-design which can support multi-stakeholder coalitions and/or its facilitators to plan, conduct, and evaluate a co-design initiative. The Canvas explicitly encourages discussing critical co-design decisions, including stakeholders’ (lack of) power, which is not often done in design.

Citation: Smeenk, W. (2023). The empathic Co-Design Canvas: A tool for supporting multi-stakeholder co-design processes. International Journal of Design, 17(2), 81-98. https://doi.org/10.57698/v17i2.05

Received September 11, 2021; Accepted April 5, 2023; Published August 31, 2023.

Copyright: © 2023 Smeenk. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: wina.smeenk@inholland.nl

Wina Smeenk has been appointed as Professor in Societal Impact Design at the Inholland University of Applied Sciences in Diemen since 2021. Moreover, she is the founder and chair of the Expertisenetwork Systemic Co-design (ESC, a network of four applied universities in the Netherlands) and a part-time self-employed empathic co-designer at Wiens ontwerperschap. Wina graduated from Delft University of Technology and spent more than ten years as a strategist and designer for various international businesses in various product sectors. Next, she helped to develop innovative design-oriented educational programs for universities of applied sciences, such as Inholland, the HAN, and the HvA, as well as THNK, the Amsterdam School of Creative Leadership, and the Faculty of Industrial Design at Eindhoven University of Technology. In 2019, she defended her Ph.D. thesis, Navigating Empathy, empathic formation in co-design processes.

Introduction

Our world has reached a tipping point. Societal challenges have become increasingly pressing. They affect us all as citizens, designers, researchers, professionals, volunteers, and voters (Smeenk, 2021, 2022). Consider our current crises, such as the climate, energy, nitrogen, inequality, COVID-19, etc. Truly understanding and tackling these challenges is difficult because no single stakeholder nor organization is responsible for them, and everything is connected, interwoven, and in a current state of change. There is mutual interaction and entanglements between people, non-humans, and technology. Next, such systemic challenges based on the relationships, interactions, and experiences between stakeholders and their environments are dynamic, which makes challenges multi-layered and evolve. Subsequently, it is hard to see the playing field, obtain a joint overview, and move forward together. This leads to stakeholders being unable or unwilling to make all kinds of important (shared) decisions and making urgent societal challenges stranded and orphaned between people, spheres of life, disciplines, and domains.

The numerous grand challenges around us demand new approaches to build alternative sustainable futures collectively. We must address them in a more integrated fashion and change our way of working together by forming so-called multi-stakeholder coalitions, in which each stakeholder from his/hers/its different spheres of life (personal, private, public, political) can play their part and responsibilities, results and credits are shared (e.g., Smeenk, 2021). Nowadays, design (and more specifically co-design), empathic design, and systemic design are increasingly seen as drivers for guiding people, teams, organizations, and coalitions toward change and transformation (e.g., Design Council, 2021; Hummels et al., 2019; Irwin, 2015; Manzini, 2015; Papanek, 1971; Sangiorgi, 2011; Stappers, 2021).

The power of design lies in its focus on people and the ability to influence and bridge gaps between different spheres of life, disciplines, and domains with creativity. Design can deal with uncertainty and is optimistic and inquisitive in nature. It envisions and depicts the unknown and is especially suited to imagining alternative futures. Moreover, an empathic co-design approach allows one to identify, share and come to grips with the different individual stakeholders’ worldviews, values, experiences, and knowledge, as well as with their shared perspectives and ambitions. This enables stakeholders to create new bonds in potential value networks or so-called coalitions and to co-imagine alternative futures together. Even more, supported by abduction logic based on values of people and mechanisms (Dorst, 2010), design can discover leverage points, develop surprising (re)frames and make creative leaps which can lead to radical fundamental societal change. Design can imagine what does not yet exist and can visualize the unknown. Moreover, as a result, design is particularly well-suited as a facilitator in fundamental change. This, however, is depending on the designer (role) as we cannot assume that all have the ability to adopt a co-design process without a naive convenor, provocateur, advocate, listener and responder.

To make this vital and empathic co-design potential work in complex systems as our grand challenges are, design itself needs to shift right along with our transforming world (e.g., Gardien et al., 2014; Sevaldson & Jones, 2019; Smeenk, 2021). Design needs to adopt new flexible strategies that support and facilitate stakeholders as non-designers in adaptively and empathically responding to dynamic and systemic contexts and value network collaborations (Brand & Rocchi, 2011).

While complex challenges point to the existence of several agendas and visions, outcomes and outputs are ambiguous and unforeseeable (e.g., Chen et al., 2016; Manzini, 2015), co-design processes are multi-layered and therefore not easy to oversee, particularly for non-designers (stakeholders from other domains) and design novices (design students). Due to the complexity of a systemic co-design challenge, multi-stakeholder coalitions often face difficulties when carrying it out. Among others, initiating stakeholders or facilitators often do not know where and how to start their journey together, which role to take or which facilitation and (reciprocal) encounters to organize, whom to involve and how to prevent marginalized stakeholders are overlooked, how to create a learning environment which fosters peoples’ collective wisdom and creativity, and realizing profound social innovation (e.g., Design Council, 2021; Irwin, 2015; Lee et al., 2018; Mattelmäki et al., 2014). Without a shared way of working, culture, structure, and a common vocabulary, coalitions may face difficulties in working on change together (e.g., Design Council, 2021; Lee et al., 2018; Rotmans & Loorbach, 2009).

In this paper’s case study, executed in a European Horizon 2020 (EU H2020) research project, we also encountered a situation where multi-stakeholders needed more knowledge and guidance in addressing societal challenges. Active local residents, self-organized in a cooperative coalition, were in need of better collaboration with the municipality, whilst the willing municipality was not (yet) organized to do so. The situation demanded a validated and practical co-design process instrument to guide them toward an energetic and new way of effectively working together.

Despite the many models, frameworks, principles, methods, and tools for collaboration to be found in co-design research (e.g., Hummels et al., 2019; Irwin, 2015; Sanders & Stappers, 2012), there also seems to be a gap in translating these research models to practice, especially if it concerns complex, systemic and dynamic societal challenges (e.g., Gaver & Bowers, 2012; Norman, 2010). The knowledge production on both sides of this so-called research-practice gap is increasingly appreciated, as well as the interactions between both (e.g., Colusso et al., 2019). Although the theory for co-design is useful for understanding the phenomena as an academic, it is often not made ready for practice situations where multiple stakeholders need to collaborate towards a common goal. Albeit, the contribution of design research into design practice is put forward as one of its quality issues (Cash et al., 2022).

To bridge this gap, co-design decisions can be seen as a concept to be shared (Cockton, 2013; Lee et al., 2018) and as a key facilitator for multiple stakeholders working together. Co-design decisions can cut across vocabularies, spheres, disciplines and domains. Decisions are less abstract than design principles and more generic than activities or methods. As such, they can be a way for stakeholders to find common ground and supply an outline for an empathic co-design process. A good example is the Design Choices Framework for Co-Creation by Lee et al. (2018). Although this framework is based on 13 co-creation projects in practice, it is not yet validated in practice. It is in fact a case in point where the academic theory needs to be translated to be useful in practice. Although Lee’s framework greatly inspires as it distinguishes clear and practical co-design decisions for stakeholder coalitions, its visual representation is rather abstract. To consider this framework as a practical co-design instrument with a specific focus on tackling societal challenges in multi-stakeholder collaborations, it requires to be evaluated and probably adjusted and/or complemented to make it more appropriate for practice.

In this paper, I present a case study where we translate the theoretical framework of Lee et al (2018) for a real-world EU H2020 co-design project. Moreover, we reveal that the ‘real-world’ stakeholders are co-translators of this framework in a so-called intermediate-level knowledge product (Höök & Löwgren, 2012; Löwgren, 2013) that represents co-design theory in a for practice and design education appropriate way and medium (Gaver & Bowers, 2012). We will co-develop and test prototypes with citizens and policymakers. Moreover, citizens as co-researchers will evaluate the prototype with a broader group of citizen participants.

This paper is organized into five sections. In the first section, co-design, empathic design, and systemic design are discussed as the theoretical background for the case study leading to the proposal of using the framework defined by Lee et al. (2018) as a base for the development of a new intermediate-level knowledge product. In the second section, the case study is introduced, and the research process is explained, followed by an analysis of the development of the empathic Co-Design Canvas. The final empathic Co-Design Canvas existing of eight co-design decision cards, which together make up the Canvas as a whole (A1 Landscape Size) is described in the third section, leading to a novel co-design framework. Based on post-case study experiences, the strengths and limitations of the Canvas in education and practice will be considered in the fourth section. In the last section, future work is discussed.

The Landscape of Co-Design

This section describes three coherent design approaches: co-design, empathic design, and systemic design. Then, co-design tools & methods are discussed. This section is ended by introducing the Design Choices Framework for Co-Creation projects of Lee et al. (2018) as a starting point for the development of an intermediate-level knowledge product (Höök & Löwgren, 2012; Löwgren, 2013) to be used by multi-stakeholder coalitions in dynamic and systemic societal challenges.

Co-Design, Empathic Design, and Systemic Design

Co-design is a democratic concept whereby people affected by design decisions are involved in or part of the shared design decision-making process (Sanoff, 1990). Moreover, it is defined as using the collective creativity throughout the entire collaborative process (Sanders & Stappers, 2008). It is a process in which actors from various disciplines share their knowledge of both the design process and the design content (Kleinsmann & Valkenburg, 2008).

Empathic design specifically addresses emotional, social, and complex design challenges for, with, and in between people (Leonard & Rayport, 1997). It suggests design approaches that consciously combine and balance objective and subjective mindsets and enables designers and stakeholders to include relevant personal experiences and feelings (Mattelmäki & Battarbee, 2002). Empathy is people’s intuitive ability to identify with others’ lived experiences, such as thoughts, feelings, motivations, emotional and mental models, values, priorities, preferences, and inner conflicts (Fulton Suri, 2003). It concerns alternating between affective experiences and cognitive processes and orientation on self and other(s) (e.g., Hess & Fila, 2016; Smeenk et al., 2019). Empathic design aims at understanding what is meaningful for people and why, and use that understanding in (shared) decision making and designing (e.g., Fulton Suri, 2003; Koskinen et al., 2003; Kouprie & Sleeswijk Visser, 2009; Smeenk, 2019).

Empathic co-design is thus a complex and multifaceted phenomenon. Especially, when conducted in multi-stakeholder settings, and aimed at multi-value creation and societal impact. Here, empathy is built among various stakeholders including the facilitator(s), designer(s) and/or researcher(s) (Holmlid et al., 2015; Mattelmäki et al., 2014). Since societal challenges affect us all, individual people (such as citizens, entrepreneurs, volunteers, and policymakers) and collectives (such as families, teams, organizations, neighborhoods, networks, and society as a whole), they require shifts in different layers and spheres. Subsequently, this empathic co-design process also demands a systemic orientation (e.g., Smeenk, 2021).

Systems thinking and systemic design has (re-)gained interest the last decade as designers are confronted with new large-scale challenges with multi-stakeholders (e.g., Design Council, 2021). Subsequently, the term systemic co-design is also emerging (Smeenk, 2021, 2022). It is important to realize that one cannot say something is a system, one can only decide to look at it as a system. In doing so, a system can be defined as a set of elements and relations which operate together towards an overarching purpose (Stappers, 2021). Systems thinking is a comprehensive approach that considers not only individual and collective elements involved, but also how the elements interrelate, how the system changes over time, and how it relates to a wider context. This approach is cross-cutting and system thinkers identify multiple (f)actors that play a role in a societal challenge. They understand that systems are uncontrollable so any intervention will set off another train of interaction which could positively reinforce a system (Design Council, 2021).

Ideally, a new co-design instrument will facilitate and promote coalitions to be flexible and adaptive in their approach of a dynamic problematic situation, clear about their common purpose, its systems’ elements and their interrelations. Herewith, the instrument facilitates and determines how coalitions can (re)frame their system. Systems thinking can provide multi-stakeholders a language to unite inputs of different disciplines to collaborate, describe and visualize, and maybe understand, predict, and improve how things are intertwined and entangled (Stappers, 2021). This way of looking gives stakeholders a possible shared (over)view to work on and with. In a practical map, Stappers (2021) explains three dimensions that are key in systemic co-design processes. First, a common holistic understanding of the system structure: how it hangs together. Second, its system dynamics: how it moves along. And third, the (facilitated) interaction within the change process: how you may (not) be able to direct it.

In systemic co-design for societal change, we thus search for places in complex systems where a small shift may lead to a fundamental change in the system as a whole (Abson et al., 2017). These so-called leverage points (Meadows, 1999) can be seen as the mechanisms in the creative abduction act for change (Dorst, 2010). Intervening and experimenting in the problematic situation is most effective at these leverage points where key relations meet. However, it is the people (individuals and collectives) that need to make that shift. Thus, their perspectives, worldviews, experiences, values, interests, relations and behaviors among others are important to understand and might need to shift along to make profound change possible (Smeenk et al., 2016; Smeenk, 2021).

Co-Design Tools and Methods

There are many Research through Design scholars describing and discussing that boundary objects (e.g., Star, 1989) or convivial tools (Sanders & Stappers, 2012) or so-called intermediate-level knowledge products (Höök & Löwgren, 2012; Löwgren, 2013) can be of help as co-design methods in change and transformation processes with multi-stakeholders from different domains, disciplines and spheres of life (e.g., Chen et al., 2016; Hummels et al., 2019; Irwin, 2015; Manzini, 2015; Smeenk, 2021). These design means can be uniquely developed for the specific situation or adapted from other research or practice fields. Think, for instance, of employing prototypes, design probes, design games, scenarios, among others. The discussion and joint elaborations of stakeholders around these practical, visual and boundary tools ideally support stakeholders in making sense of complexity, articulating personal values, knowledge, experiences and feelings, leveraging deep engagement, facilitating collaboration, unlocking empathy, creating shared understanding of values and mechanisms and generating beneficial opportunities and frames for change in shared problematic situations (e.g., Carlile, 2002; Hakio & Mattelmäki, 2019; Holmlid et al., 2015). These opportunities, leverage points, and frames encourage and include new organizational systemic co-design structures, accompanying approaches, a coherent culture, and subsequent social innovations (Rotmans & Loorbach, 2009).

Design Choices Framework for Co-Creation

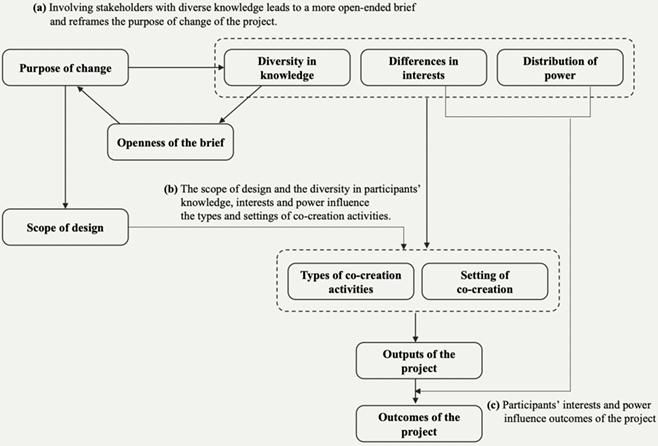

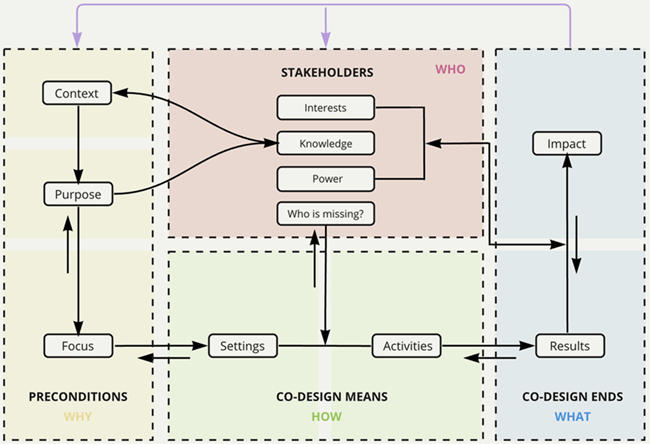

As mentioned before, the framework of Lee et al. (2018) provides the design research community and practice with an insightful structure and vocabulary that can help to explain what kind of key dimensions systemic co-design challenges are built on, what influences the formulation of these processes and informs the selection and development of working approaches and co-design activities. Based on a cross-case analysis of 13 co-creation projects in 3 domains (design research, process innovation, and service innovation), they identified, conceptualized, and proposed 10 underlining key design choices grouped into four categories in the Design Choices Framework for Co-Creation projects, see Figure 1. They define co-creation as creative activities and a co-creation of knowledge of various stakeholders in a design or innovation project (Lee et al., 2018). The four categories they distinguish are design choices related to: project preconditions, participants, co-creation events, and project results. Below they are discussed in more detail.

Figure 1. The relations of the Design Choices Framework for Co-Creation Projects (Lee et al., 2018, p. 28).

Preconditions

First, design choices related to the category project preconditions set the ground for the project to start and for framing the overall scope, purpose, and mode of the project. These preconditions involve the following three explicit design choices. Beginning, the openness of the brief describes the choice between, for example, a more problem-solving or exploratory mode of inquiry with which the project approaches co-creation goals. Next, the purpose of change can vary from customer experiences (people level) to organizational practices and culture (organizational level) or an entire service system and collaboration network (cross-organizational/system level). It is a visionary long-term decision and agenda setting, and links with later discussion on the decision impact. Further, the scope of design concerns what is to be designed during co-creation activities. Moreover, Lee et al. (2018) argue that the openness of the brief informs the purpose of change and the purpose of change the scope of design.

Participants

Second, the category participants concern three design choices: who has relevant knowledge, what types of interests are involved, and what power dynamics. Beginning, the diversity in knowledge involves both holistic understanding (participants together must possess all the requisite knowledge of what they develop) and the hologram structure of a co-creative group (all practice-based knowledge of participants involved in order to be successful in implementation). Next, considering the differences in interests of participants makes them aware of the variety and complexity. Last, the distribution of power considers participants’ power dynamics. Moreover, Lee et al. (2018) argue that participants’ differences in interests, diversity in knowledge, and distribution of power within the project informs the purpose of design and the design scope.

Co-Creation Events

Third, design choices related to co-creation events consider what types of co-creation activities are chosen and developed according to the project preconditions and participants, and what the settings should be like to achieve desired outcomes. The type of design activities aims at eliciting participant knowledge and generating design opportunities with or without generative design means. Choosing a specific physical or material design setting has an influence on the activities.

Project Results

This is the fourth and last category that distinguishes from immediate results and deliverables as outputs of the project to further implementation and impacts as outcomes of the project. Project outputs can range from ideas to reports, artifacts, scenarios, etc., established by participants, designers, and/or researchers. The project outcomes go beyond outputs, they can involve new mindsets, culture, processes, etc., and directly affect participants.

An Intermediate-Level Knowledge Product

Lee et al.’s (2018) framework can provide stakeholders working on grand challenges an overview and help them to plan and assess a co-design process by giving a more systematic understanding of key attributes, dimensions, and co-design decisions in processes surrounded by social contingencies. Moreover, the framework demonstrates influential relations among the different decisions, which points to an iterative and complex process.

Although Lee’s framework greatly inspires as it distinguishes clear and practical co-design decisions for stakeholder coalitions, its visual representation is rather abstract. Understanding this framework might be challenging for those new to co-design, whether design students or non-designer stakeholders from other domains. Visual reproduction as a flowchart might not be the appropriate way to disseminate and communicate this intermediate-level knowledge to practice (Höök & Löwgren, 2012; Löwgren, 2013). We need a better, more understandable, useful, and attractive representation in an appropriate communication medium for practice and education (Gaver & Bowers, 2012). Moreover, some of Lee’s vocabulary and terminology (e.g., project, participants, customers, target group, etc.) does not do justice to the transformative, more pro-active context where multi-stakeholder coalitions (including designers and researchers) take ownership of the process and intrinsically work together to reach societal impact. Therefore, the concept could be adjusted and complemented to make it into a more appealing, playful, and a practical intermediate-level knowledge tool (Höök & Löwgren, 2012; Löwgren, 2013) for practice and education with a specific focus on tackling societal challenges in multi-stakeholder collaborations. In the next section, I will illustrate how we arrived at the Co-Design Canvas based on the lessons of above theory and the following empirical case study.

Case Study

This paper’s empirical case study unfolds in the context of a of a EU H2020 research project research project. This research project aimed to experiment with new co-design methodologies, to co-discover opportunities for local challenges, and to stimulate bottom-up initiatives in ten pilots across Europe. We conducted our study from March 2020—just before the COVID-19 pandemic struck—until February 2021.

Our pilot project was focused on addressing questions of quality of life in a small, aging, and shrinking Dutch village (for more details, see www.siscodeproject.eu). It aimed to discover how participatory policymaking can stimulate bottom-up initiatives and vice versa by developing tools for participatory policymaking that increase citizen engagement, a future-proof community, and more confidence in multi-stakeholder collaborations. Citizens, policymakers, and a strategist formed a multi-stakeholder coalition for this project.

In this research context, the existing collaboration between citizens and policymakers was not effective and led to tensions. Both citizens and policymakers indicated missing guidance and an instrument to facilitate their collaboration on equal and transparent terms, in partnership and with trust to let citizen-initiatives grow and flourish and realize change. The coalition needed more focus and shared priorities, as well as a good alignment of the different interests and responsibilities, taking into account the municipality’s organizational (in)possibilities, structure, and decision-making processes.

During the research, we developed a co-design instrument that we named the empathic Co-Design Canvas based on Lee et al.’s (2018) framework. We tested the first prototype of the instrument within the project context. We as researchers then analysed the empirical data to discover how the instrument might be improved to create a second prototype. Subsequently, this second prototype was evaluated in the project context before the final version of the instrument was realized.

In the research activity sessions described below, we observed how the instrument emerged and was used. During the research, we asked open questions about the instrument’s usability, guidance, elements and effect on collaborations and insights. To evaluate these reflections objectively two researchers scanned the verbatim transcriptions independently to find quotes providing evidence. These findings were discussed until agreement was found. Moreover, observations were taken along. It must be noted that based on the empirical work with the stakeholders (citizens, municipality) in real-life settings and the theoretical exploration, we made some instrument design decisions ourselves in the development of the prototypes which had influence on and changed some of the starting points from the framework of Lee et al. (2018).

Participants

The above research process involved 25 stakeholders attending: 21 citizens, three policymakers, and one strategist. They represented diversity along several key dimensions. First, all citizens were engaged residents committed to actively contributing to their community. We established contact with the core four citizens as they represent subcommunities connected to different bottom-up and cooperative initiatives. Second, all policymakers, including one alderman and two government officials, focus on citizen participation and citizen engagement at the Municipality Department of Social Development. Third, the strategist is a representant of the EU H2020 project. Together, they also represent a diverse group of people regarding age, gender, position, and affiliation.

Approach

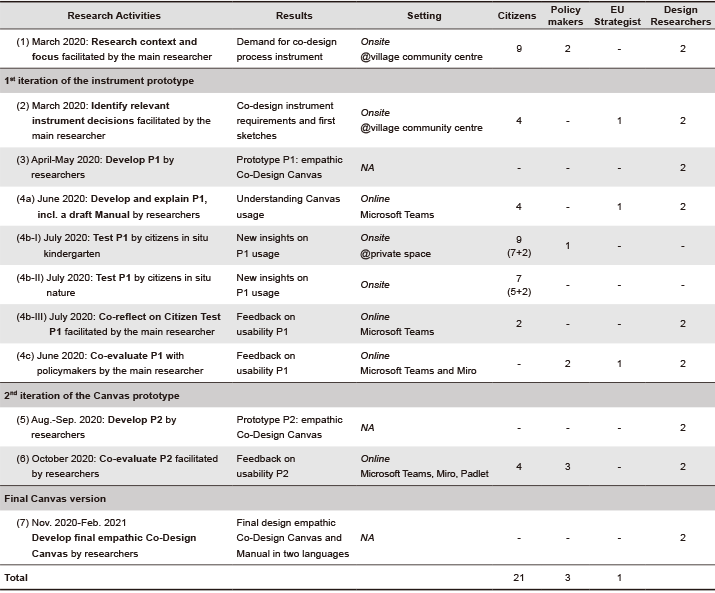

The research approach consisted of seven main activities, as depicted in Table 1. I will discuss these activities in detail below.

Table 1. Summary of the research activities.

The first physical co-design session was supported by creative method cards (Smeenk & Willenborg, 2017, 2022) and conducted with nine citizens and two policymakers. Here, the research project context and focus were identified and developed.

In a second co-design session onsite with four core citizens only (due to COVID-19 outbreak), I introduced the co-design decisions defined by Lee et al. (2018) as labels only. By presenting these decisions separately on cards as possible co-design ingredients, the citizens were inspired to discuss if these decisions felt relevant in their process and to sketch their relations. The activities and settings decisions were postponed to discuss in research activity 5 due to time constraints.

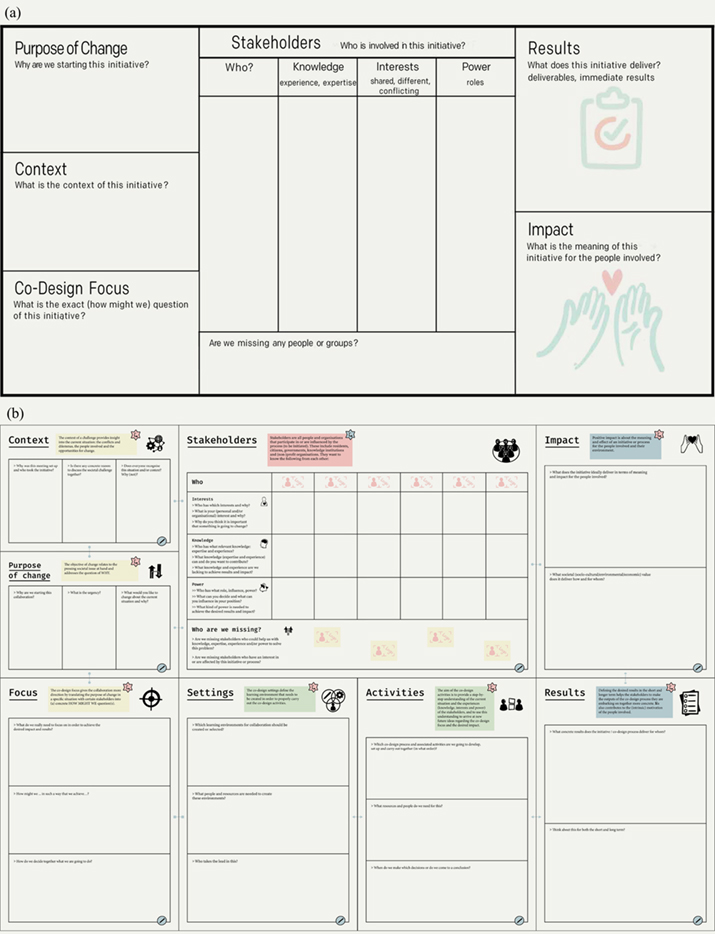

In the third activity, we analyzed and synthesized the preliminary empirical data of aforementioned two sessions including the session set up, tools used, pictures and videos made, co-created artefacts, stakeholders’ first instrument sketches and accompanying requirements. We translated the empirical insights and theoretical insights from literature into a first instrument prototype P1, see Figure 2a.

The next activities were split up in 5 sub-activities, see Table 1. The first prototype P1 was tested three times on usability. Once with the municipality facilitated by the researchers (research activity 4c) and twice facilitated by the citizens (research activity see table 4b-I & 4b-II), who as two co-research teams, tested the Canvas in two real-life contexts involving a broader group of residents. In order to conduct this test properly and with confidence, we beforehand provided the four citizen co-researchers with an online explanation of prototype P1 and its draft manual (research activity 4a). The test was subjected to a semi-structured interview list supported by a set of guidelines that questioned whether the design decisions identified, their terminology, order, position, and interrelationships were applicable and valuable in practice and, if so, in what way. The four citizen co-researchers each organized a test (research activity 4b-I & II), relating to one of two pressing challenges: the future of the local kindergarten and a climate landscape challenge. Per team, one citizen researcher facilitated the session and the other took notes. Afterwards, we organized an online co-reflection session (research see Table 4b-III). In this way, citizen researchers could share their experience with the prototype P1 as a co-design instrument and discuss their role as facilitators. Subsequently, a test was conducted with the policymakers online (research activity 4c) aiming to test the same prototype P1 by using the EU project as subject of discussion and supported by the same guidelines as in the citizen test. We used the online tool Miro to display prototype P1 and to collect and record questions, and discussion points.

In the fifth activity, we analyzed and synthesized the rich empirical data of the earlier activities and incorporated the test findings in a refined second prototype P2, see Figure 2b.

In the sixth activity, the four citizen co-researchers, the alderman, two government officials, and the EU-project representative were invited (as they had been the core of the research process) to evaluate the usability of prototype P2. First, this prototype was plenary presented. Then, two parallel interactive sessions in heterogeneous teams were conducted. In preparation for this session, we already filled in the co-design decisions context, purpose, and focus based on the content discussions in earlier sessions with the coalition. Each team was then facilitated by one researcher. We guided the stakeholders through all prototype cards on Miro alternating between the participants providing individual input and co-reflecting on each other’s input. The session was concluded plenary using the online software Padlet to collect the pros and cons of prototype P2, as well as opportunities for future implementation.

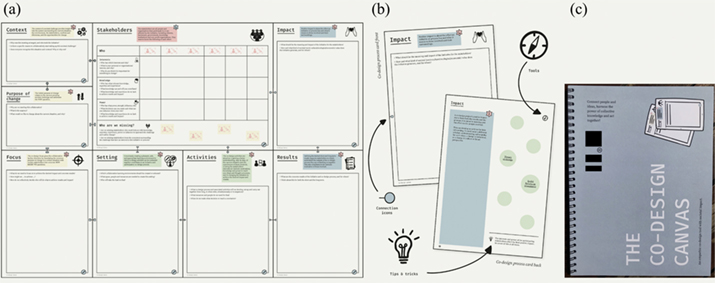

Last, the above co-evaluations enabled us to draw up the final empathic Co-Design Canvas with accompanying Manual as depicted in Figure 3.

Analysis

In the following part, I discuss the generic decisions made regarding the Canvas representation, vocabulary, and guidance.

Canvas Representation, Vocabulary, and Guidance

In co-developing and evaluating the co-design instrument prototypes P1 and P2 with citizens and policymakers on their usability, we gained new insights that led to the final structure and representation of the so-called Co-Design Canvas.

To start with, in their first co-design process instrument sketch, citizens clearly expressed it was important to put effort in making the instrument attractive and practically usable. They were inspired by the visual form of the Business Model Canvas (BMC) of Osterwalder & Pigneur (2010). This BMC is a well-known visual tool for exploring and designing new business models. It includes separate building blocks that together give an overview of the ingredients of business modelling and the process involved. Likewise, citizens stated a co-design instrument should connect all design decisions/elements that define and affect a co-design process.

Next, from both the theory (e.g., Design Council, 2021) and empirical research with stakeholders, we as researchers learned to use a vocabulary and terminology that is clearly understood across domains, disciplines, spheres of life and people, and fits the co-design process for societal challenges and impact. Therefore, it was decided that the initial title of Lee et al. (2018) required adaptation. The title Design Choices Framework for Co-creation was changed into the empathic Co-Design Canvas. Citizens stated that—compared to the framework—the term Canvas is a more familiar, accessible, and practical term for novices in design and research.

Figure 2. The empathic Co-Design Canvas: (a) prototype P1 and (b) prototype P2.

Moreover, the term empathy was added to the title based on the theoretical and empirical explorations. We observed stakeholders working with the Canvas to consciously exchange personal interests, experiences, feelings, knowledge, perceived (lack of) power, and desired results and impact. Herewith, stakeholders continuously distinguish between orientation on self and other, and between affective experiences and cognitive processes, which is known as empathic formation (e.g., Hess & Fila, 2016; Smeenk et al., 2019). In addition, while Lee et al. (2018) mention a project team, societal challenges require a coalition of stakeholders that want to take initiative together. They work in sub-teams toward a joint purpose. This concerns more people than one project team can hold and more activities than co-creation alone. It includes a project-portfolio and a co-design process beyond co-creation.

At the last evaluation, both citizens and policymakers pointed to the crucial role of (professional) facilitation. They found that a facilitator is required. Yet, this can be someone from inside the coalition with experience and expertise in facilitation. Besides, they stated that facilitators need preparation via a Manual to flexibly guide the multi-stakeholder coalition through the co-design decision cards. One of the policymakers also suggested organizing training-session within the municipality to learn how to work with the empathic Co-Design Canvas and, thus, how to implement new, co-creative, and participatory ways of working. Besides, we learned that the Canvas was missing guidance, like short descriptions to explain the aim of each co-design decision. Therefore, we added these descriptions in colored blocks next to the title of each card.

Moreover, we explicated the existing short questions from prototype P1 on the request of citizens and expanded them in prototype P2. Yet, this also led to a problem; stakeholders stated that “the layout of each separate card suggests that each single guiding question should be answered.” The stakeholders were afraid that this could lead to ticking boxes instead of having a constructive dialogue/conversation and taking the questions as inspiration only. Therefore, in the final empathic Co-Design Canvas, the guiding questions are positioned beneath each card title to guide stakeholders in their discussions with each other. Moving the questions to the top of the front side of the cards provided another advantage: more blank space to write, draw, or add sticky notes. Besides, we used the backside of the cards to provide more in detail explanations of the specific co-design decisions, to suggest tools, as well as to add tips and tricks. See Figure 3b. Moreover, we added detailed visual elements for guidance. Lee’s (2018) four framework categories are represented by four subtle colours, for example. Next, symbols are created for each co-design decision card and signs are added that connect the cards like a puzzle and show its interrelations.

Figure 3. The final empathic Co-Design Canvas: (a) the empathic Co-Design Canvas existing of 8 cards, (b) details of the front and back side of the cards, and (c) the accompanying Manual. The cards can be printed on any standard A3/A4-printer and are provided under a Creative Commons license and to be found on the project’s website.

The Final empathic Co-Design Canvas

Compared to Lee et al. (2018), the empathic Co-Design Canvas now exists in four categories: co-design preconditions (why), co-design stakeholders (who), co-design ends (what), and co-design means (how). Moreover, eight co-design decision cards together make up the Canvas as a whole (A1 Landscape Size). It is important to note that the relations between the cards are more important than the separate card elements, and iterating through the Canvas and its cards is the advice. The eight cards have different sizes: the co-design context (A5 Size Landscape), purpose (A5 Landscape Size), focus (A4 Portrait Size), stakeholders (A3 Landscape Size), activities (A4 Portrait Size), settings (A4 Size Portrait), results (A4 Size Portrait), and impact (A4 Portrait Size).

The final Canvas comes with an illustrated Manual that provides background information and guiding tips and tricks on facilitation and tools (see Figure 3c). We created a digital PDF and a limited edition printed book version of the Canvas Manual in two languages. The Co-Design Canvas is freely accessible and easy to use. Below, I will discuss the cards per category in more detail.

Co-Design Preconditions (Why)

As mentioned in our theoretical background section, the co-design decisions related to Lee’s (2018) initial category preconditions set the ground for the co-design process to start: WHY to start a co-design initiative? After our empirical work, the category preconditions still involves three explicit design decisions, yet terms changed. The empathic Co-Design Canvas preconditions exist of three yellow cards positioned on the left side of the Canvas: co-design context, purpose, and focus. They will be discussed in detail below.

The Co-Design Context

The first initial design decision of Lee et al. (2018) openness of the brief (i.e., the choice between a more problem solving or exploratory mode of inquiry) was already changed in prototype 1 after a discussion with the citizens in research activity 2 (Table 1). In societal challenges, there is no specific design brief. Co-design processes involve an open-ended character and many stakeholders (Dorst, 2010; Lee et al., 2018). This initial term is, therefore, not very suitable. Even so, in our case study, we found that no explicit brief nor project description was set up. However, the EU H2020 project did provide a complicated context in which policymakers and citizens together identified specific challenging situations around participation that required a joined change process. We therefore decided to change the term of this co-design decision card into the term context. This card is positioned on the top left of the Canvas as the problematic context of a societal challenge forms a natural starting point for a co-design process. Subsequently, the complicated situation asks for an aspired common purpose.

The Co-Design Purpose

Another initial design decision of Lee et al. (2018) purpose of change (i.e., what and where in the system we aspire to change, why are we starting this initiative) led to confusion and discussion among the citizen participants joining the two Canvas’ prototype 2 sessions with our co-researcher citizens. We observed that the term was interpreted differently by them than mend by Lee et al., making them rebellious and resistant to change instead of opening up to discuss what can be done (searching for a new purpose) about the complicated context. The citizen participants did not want the local school to close, and farmers did not want to adapt to new climate regulations. “I want to preserve what I have.” All citizen co-researcher facilitators of the sessions observed that the citizen participants needed an example of a purpose for change accompanied by inspiring stories/narratives to be motivated by their role in this “necessity of transformation.” Due to the confusion, we decided to delete the term change and renamed this co-design decision into purpose only. This stand-alone term is better understood, much stronger, and underlines the necessity of transformation. It concerns agenda setting, vision, and long-term decisions. It also links closely with the impact card discussed later. The co-design purpose card is positioned in the middle left of the Canvas.

The Co-Design Focus

The initial decision scope of design (i.e., what is to be designed during co-creation activities) was like purpose of change already changed in prototype P1 after a discussion with the citizens in research activity 2 (Table 1). According to the citizens, the term scope was -apart from being a less common term in our native language- seen as too specific already. Our citizens stated to prefer the term focus “as focus sets the direction of the co-design process, but does not yet provide requirements.” They appreciated focus more since they stated to “still need explorations to find out what exactly to design.” We discussed that a co-design focus is plural: it exists of several sub-design questions formulated in: how can we… in order to deliver… It is these sub-questions and a portfolio of subprojects that can lead to multi-value creation and impact wished for by combining several concrete results. The co-design focus sub-questions are in turn the starting point for various design activities to employ in specific sub-teams and accompanying settings. In fact, the co-design focus is about framing and reframing. It might be seen as the synthesis card of the top part of the Canvas. The co-design focus card is positioned on the left bottom of the Canvas.

The Co-Design Stakeholders (Who)

The initial co-design category about participants (i.e., WHO has relevant knowledge, interest, and power) is very relevant to societal challenges. However, in these complex challenges, we all have a stake: stakeholders, students, designers, and researchers. Therefore, we directly changed this term in prototype P1 in stakeholders after a discussion with the citizens in research activity 2 (Table 1). Citizens explicitly stated to prefer using the term stakeholder instead of participant as they did not feel like participating, but taking ownership of the transformation they jointly wanted to make. Their being co-researchers brings evidence for that. The term participant is then not active enough and refers to being invited to participate in a session instead of partnering up and taking co-initiative and co-responsibility (Arnstein, 1969). In an empathic co-design process, stakeholders have an intrinsic motivation and want to be (the) change (Hummels et al., 2019). The red co-design stakeholder card is positioned on the top of the Canvas and forms the heart of the Canvas. Within the card, three sub-decisions are distinguished: stakeholders’ interest, knowledge, and power. In prototype P2, we adapted this order as prototype P1 tests learned that people almost always start with explaining their personal or organisational interest in a specific problematic situation before expressing their knowledge, experiences and power. Moreover, we observed in these tests that each sub-design decision element can be discussed from an individual point of view and a collective one. For the latter, think, for example, of the layers of teams-organizations-coalition or streets-neighborhoods-cities-countries. Therefore, we incorporated these elements in the second prototype by setting up a table in the Canvas. The rows consist of the stakeholder sub-decisions and the columns consist of both the individual person (picture) and the collective(s) (logo) they represent. Including individual and collective perspectives makes the Canvas more systemic (e.g., Design Council, 2021; Smeenk, 2021). Besides, in prototype P1 a co-design decision was added: who is missing at the table, both individuals and groups. Common theory on participatory processes and missing out on the policymakers in research activity 2 due to the COVID-19 outbreak made the researchers decide to incorporate this extra decision compared to Lee et al. (2018).

Stakeholder Interest

The initial sub-decision about stakeholder interest (i.e., awareness of differences in motivations and consequent complexity) was recognized by the citizens and policymakers and did not change. In the tests, we observed that in societal challenges stakeholders can have shared, different, conflicting and/or no interest at all. In a test, a stakeholder stated that “understanding each other expands by exchanging different interests and engaging with one another.”

Stakeholder Knowledge

The initial sub-decision about stakeholder knowledge (i.e., aware of who provides what relevant knowledge) was recognized by the citizens and policymakers and did not change. In research activity 2, citizens however mentioned that the terms holistic knowledge and hologram knowledge were quite hard to understand. Based on this discussion, we translated this knowledge in experiential knowledge and expertise knowledge in prototype P1. The first provides for real-life experiences in problematic situations. The latter can contain process, organizational, or thematic expertise and capacity, among others.

Stakeholder Power

The initial sub-decision about stakeholder power (i.e., distribution of power and power dynamics) was also recognized by the citizens and policymakers. Yet, power was also a major point of discussion among the citizen participants in the tests as well as among the citizen co-researchers and the policymakers. This might be a cultural issue, as in our country, power often has negative connotations. Some female citizens even described it as a nasty word at first. They therefore discussed alternatives, such as strength, influence, or capacity, which could have more positive connotations. However, interestingly enough, citizens and policymakers ultimately agreed that although “talking about power makes people feel uncomfortable, this does not mean that we should ignore it.”

On the contrary, theory learns that one of the main reasons coalitions are ineffective is because unequal power relations play a role but are not openly addressed as such (e.g., Chen et al., 2016). Moreover, citizen participants stated they “do not feel to have power because the municipality is in control.” Yet, our citizen co-researchers noted that power could have a broader meaning than financial, decision-making, or legal power. In one test with citizen participants, one participant stated to feel powerless in the challenge at stake. Yet, throughout the prototype P2 test discussions, this participant was observed to get a new insight into the different factors involved in power, such as expertise, ownership, willingness, network, and support. It was observed that this provided her with a new perspective: “I can have power and agency!”

In the last test with citizens and policymakers, we observed that taking your power or not taking your power can affect the co-design activities and its settings and subsequently affects results and impact. If stakeholders do not take the responsibility that comes with their role (power) they might frustrate and hinder progress. An alderman not taking a decision on budget or permits is a good example. Moreover, it was appreciated that omnipresent power is explicitly discussed at an early stage of the process and made visible in the Canvas. In line with the experience of the citizens, all policymakers agreed that openly and explicitly addressing knowledge, power, and interests, and aligning expectations from the start, is important. In that sense, the Canvas prototype P2 helped them become more aware of their own power and role in the process, and how power imbalances can lead to misunderstandings and insensitive decisions.

Who Is Missing?

The new sub-decision who is missing (i.e., which individuals, groups, teams or organizations are not at the table) was introduced by the citizens when the policymakers were missing due to Covid-19.

Co-Design Ends (What)

As mentioned in our theoretical background section, the co-design decisions related to the initial category project results express WHAT the process leads to. It concerns intangible more long-term results (such as societal and environmental impact, behavioral and system change, symbiotic relationships, etc.) and tangible more concrete short-term results (such as new participatory policymaking working processes, increased successful initiatives, etc.). Although not visible in the Canvas itself, we changed the category term to co-design ends due to insights that the project result is not the end we work towards in societal challenges. After our empirical work, the co-design ends category still involves two explicit design decisions that changed into concrete results and impact. These cards have a blue color and are positioned above each other on the right side of the Canvas. They will be discussed in detail below.

Co-Design Results

The initial co-design decision about outputs (i.e., the immediate results and deliverables to further implement) was already changed in prototype P1 after a discussion with the citizens in research activity 2 (Table 1). According to the citizens, concrete results were a better term here than outputs regarding the context of societal challenges and our native language. Concrete results concern short-term decisions and range from ideas to reports, artifacts, scenarios, etc., established by stakeholders, designers, and researchers together. The co-design results card is positioned on the bottom right of the Canvas as it relates more to the co-design focus positioned at the bottom as well.

Co-Design Impact

The initial co-design decision about outcomes (i.e., impacts of the process) was already changed in prototype P1 after a discussion with the citizens in research activity 2 (Table 1). According to the citizens, impact was a better term here regarding the context of societal challenges and our native language. Transformation and impact require time, stamina, and vision (e.g., Irwin, 2015). They go beyond concrete results. It ranges from new mindsets to culture, processes, etc., and has a direct effect on stakeholders. The blue co-design impact card is positioned on the top right of the Canvas as impact relates more to context and purpose, which both are positioned on the Canvas top as well.

Co-Design Means (How)

As mentioned in our theoretical background section, the co-design decisions related to the initial category co-creation events express what the process’ activities and its settings constitutes of: HOW to co-design. Although not visible in the Canvas, we changed the category term to co-design means matching the renamed design ends category and explicating how to co-design. After our empirical work, the co-design means category still involves two explicit design decisions which terms did not change. The cards have a green color and are positioned next to each other in the middle on the Canvas bottom.

Co-Design Activities

The initial co-design decision about activities (i.e., what activity types to choose or develop with regard to preconditions and stakeholders) was recognized by the citizens and policymakers. The co-design activities are mend to relate to and are specifically set up to answer each sub-question raised in the co-design focus card. Each activity involves a specific learning setting and a (sub)group of stakeholders matching the quest. The co-design activities card is positioned next to the co-design settings card, and the co-design results card is in the middle of the Canvas bottom as it relates to both. The type of design activities aim at eliciting stakeholders’ knowledge and power, and generating design opportunities with or without generative design means.

Co-Design Settings

The initial co-design decision about settings (i.e., what kind of hybrid learning environment is required to achieve desired ends) was also recognized by the citizens and policymakers. Co-design activities require an accompanying online, physical, or material design setting for co-learning. The co-design settings card is positioned between the co-design focus and the co-design activities cards in the middle of the Canvas bottom as it relates to both.

Co-Design Framework

Finally, we compared the final empathic Co-Design Canvas structure to the initial framework structure of Lee et al. (2018), see Figure 1. It was observed that most of the relationships given by Lee et al. (2018) are covered in the Canvas by how the cards link together. The only influential relationships the Canvas could not show as clearly as the framework of Lee et al. (2018) did are the stakeholder sub-decisions’ interest and power with impact. However, in Figure 4, we could make them visible. Moreover, we closed the loop by clarifying that impact influences the context and stakeholders involved (purple line).

Figure 4. The theory behind the empathic Co-Design Canvas: The framework based on the Canvas.

Case Study Findings

The study demonstrated that the empathic Co-Design Canvas can be used by multiple stakeholders when planning, conducting, and evaluating a co-design process in a variety of contexts. The Canvas exists of eight co-design decision cards. They together provide an overview of and structure by a set of relevant co-design decisions in which individual and collective stakeholders can be equally recognized, heard, and empowered. In the research activities, we observed that the coalition appreciated working with this co-design instrument and the overview it provides.

The coalition described the final Co-Design Canvas as a “concrete, clear, visually attractive, but also playful tool that can be used for different types of challenges.” According to this coalition, the value of the Canvas lies primarily in the shared vocabulary, shared decision-making, an overview of the process, and the consequently open and transparent dialogue about each other’s aspirations, interests, and knowledge.

Moreover, the citizen co-researchers experienced their sessions with citizens as “fun, inspiring, and energetic” and stated that “the conversations kept on going.” Besides, they observed the Canvas to “result in new insights, and provided for a shared language and mutual understanding of the challenge at stake.” In one case, they observed that the Canvas brought new stakeholders to the table who were previously unaware of each other’s role in the challenge at stake. In addition, all citizen co-researchers reported that the Canvas helped citizen participants keep track of the co-design process: “we know what to expect.”

The policymakers expressed that “addressing these fundamental elements (i.e., design decisions) in any collaboration helps with defining a clear starting point and a common vision. Yet, this does not imply that the purpose should be identical for every stakeholder from the start. But it is possible to find common ground by sharing and openly discussing the different perspectives at the beginning. The Canvas can then help one see and understand the bigger picture.”

As such, this case study contributes intermediate-level knowledge (Höök & Löwgren, 2013) in three ways. First, as a research instrument, the empathic Co-Design Canvas elicits knowledge about its stakeholders’ perspectives and personal and professional life. Second, as a participation instrument, the empathic Co-Design Canvas provides stakeholders to have an influence on their life: it can emancipate and democratize stakeholders. Third, as an educative instrument, the empathic Co-Design Canvas builds empathic co-design capacity with stakeholders.

Moreover, the coalition of policymakers and citizens stated that they were pleasantly surprised to co-deliver a Canvas that serves as a valuable empathic and maybe even systemic co-design process instrument. Not only for their own local community that it was designed for but more generic. They felt their participation in this research project delivered meaningful results.

As the key aim of the EU H2020 project was to support municipality policymakers and citizens with an instrument that accelerates participation and democratizes through transparent discussions and accessible working processes, we might have succeeded together. However, it is still unclear to what extent the Canvas will be implemented in the municipality’s future strategies. Yet, we observed that the Canvas is being embraced by all stakeholders as a clear instrument for a new way of working which fits the local context.

Case Study Discussion

Due to COVID-19 and accompanying meeting restrictions, it was difficult to really assess the effectiveness and impact of the empathic Co-Design Canvas, especially in its in-situ use and with a broader range of stakeholders (scale-up). Moreover, it is too soon to evaluate whether this journey actually led to social innovation and transformation in the municipality, and if citizens’ initiatives will achieve the desired impact in the long run due to a better collaboration.

It was, however, a tremendous learning experience for the whole coalition (including researchers) and stakeholder engagement was definitely strengthened. New collaborations have been formed and more people are involved in the bottom-up citizen initiatives. According to Mulder et al. (2022), these changes in practice and stakeholder self-reported improvements might already hint to impact.

Moreover, the research process seems to have increased awareness at several levels. First, during the project we saw open mindsets and postures grow within stakeholders. Second, the coalition discussed difficult issues such as equal involvement, shared responsibilities, and empathy from which I conclude that there is greater understanding and trust between municipality and citizens. Third, stakeholder capacity grew in terms of collaboration and design process knowledge and skills. And finally, this EU H2020 project created awareness about the value, opportunities, and challenges of co-design in policymaking.

There are also points for attention. Multi-stakeholders need more than the Canvas to change together. Societal change requires time, stamina, and a long horizon (Irwin, 2015). It is important that stakeholders have a drive for change but also realize the long process they are embarking on with each other. Working with the Canvas throughout the entire co-design process is essential, making it a sustainable and co-evolving process by iterating. Another consideration is the commitment of all individual and collective stakeholders. This relates to be change (Hummels et al., 2019): being responsible, ethical, trustworthy, respectful, and curious, and practicing this by listening, acting, reflecting, embodying, and being courageous and taking risks. Subsequently, it is essential to agree to disagree, dare to fail, iterate, and reframe again (Irwin, 2015). Furthermore, it is vital to be aware of (perceived) power asymmetries between stakeholders since these influence collaborations. Some stakeholders might be afraid of or hostile towards power and hierarchy; others may love it, while some are willing to share their power (Arnstein,1969; Chen et al., 2016). This all requires (external) guidance, experience, and/or training. In the collaboration, this needs attention, and it is questionable whether a Manual is enough to create such awareness, commitment and taking ownership. Therefore, facilitation is key. Last, the involvement of the citizens and policy makers in making decisions about the Canvas in our case study might also helped them see the value of it and take ownership.

Post Case-Study Canvas Experiences in Practice

Since the case study was concluded the final Canvas could be shared broadly. It was disseminated via the website of the EU H2020 project, my affiliation, and the project consortium. I also presented it at various conferences. Many researchers and tutors have utilized the Canvas in quite a few online and offline settings as a planning, analyzing, and evaluation instrument of co-design projects. It is applied in a variety of real-life challenges with several multi-stakeholder coalitions concerning a diversity of systemic societal themes, such as a healthy start for babies of pregnant teenagers and exclusion due to overtourism, among others. On the other hand, the Canvas is also used on more abstract topics within our organization, such as making living labs useful for both education, research and practice, and setting up subsidy research project collaborations with practice and multi-universities. Moreover, in educational trainings and workshops, the Canvas is used for making creative student teams and tutors understand what empathic co-design constitutes of and for building empathic co-design capacity. Evenso, a book will be published at BIS publishers in the autumn of 2023.

The duration in which we used the Canvas ranges from a year process to 1.5 hour single workshops. Settings differ from online webinars, streamed and live conferences to being used in Miro & Mural and offline in sessions, workshops and trainings. Moreover, the Canvas was applied with or without our facilitation. As far as I know, the Canvas and its Manual is currently being used in at least two other applied universities without our facilitation.

What we learn from this is that this boundary object (Star, 1989) resonates incredibly well in practice within different domains, disciplines, spheres of life, people and with a diversity of creative and non-creative professionals working together in coalitions towards change. The rich mediation of the Canvas as a boundary object might have more impact in practice than this article might have, which connects to the ongoing discussion of the role of design practice in academic research (Gaver & Bowers, 2012; Löwgren, 2013; Stolterman, 2008). We have received many positive reactions and responses from academics, policymakers, citizens, business, the creative industry, educators and students, demonstrating the significance and high demand for an instrument like the empathic Co-Design Canvas. This success also has its downside. We started to interview first users of the Canvas but were not able to continue to follow up in a rigorous way due to our greatly increased performance and limited resources.

However, we did use and evaluate the Canvas in an experimental research project about safety at a chemical industry plot financed by ClickNL. It is beyond the scope of this article to go into more detail because it is a project in itself. Yet, I can share that the collaborating partners from the chemical industry and other applied universities involved in this project stated that they observed coalitions working “more diagonal through the layers of the system” which implies a change in approach and structure, “with more trust in each other” pointing at a change in culture, and “leading to new insights on common and opposite values and possible leverage points” directing towards a co-design approach in line with transforming the culture, approach, and structure (Rotmans & Loorbach, 2009). This resonates with other feedback we collected. I will discuss the strengths and recommendations for the Canvas below.

Co-Design Canvas Strengths and Recommendations

The above experiences brought lessons for practice, which can lead to new research questions or insights for the Canvas on topics such as Canvas introduction, structure, overview, ownership, level playing field, on- and offline usage, text versus visualizations, commoning, iterations, design phases, and playfulness.

Strengths

First, we learned that it is important to give a proper introduction of the Canvas as a means to an end, and to then introduce the problematic context shortly. Moreover, most of the times, stakeholders do not know each other well at a first Canvas session and we observed that it works really well to use the red stakeholder card as a means for introduction. By exchanging your personal interest, knowledge and power stakeholders can demonstrate who they are and how they personally relate to the challenge at stake and how the organization or group they represent does. During such an introduction, a capable facilitating listener can already hear aspirations for impact and concrete result elements coming up by giving rise to a more explicit common purpose. In other words, the Canvas cards are already dynamically filled.

Second, the value of the Canvas is seen in the overview, structure and continuity it provides stakeholders who join the sessions. However, some state “one needs to experience the Canvas to really see its value. Learning while doing”. A stakeholder stated, “as an instrument the Canvas creates trust in the process.” Another stakeholder pointed out that “the Canvas provides structure and concrete actions, so it is not completely without any obligation.” Yet, success depends on who takes responsibility.

An interesting apprehension concerned the ownership of the Co-Design Canvas. While the Canvas itself is not owned by anyone—as it is meant to be used by different coalitions in multiple contexts—the ownership remark is noteworthy as the underlying question seems to be about who has control over the process. An external independent facilitator might be advisable.

When the Canvas is new for all stakeholders it can create a level playing field. We found the stakeholder card is highly appreciated in this. Stakeholders value the openness and learning to look beyond one’s own borders. They may have assumptions about each other, but the Canvas leads to awareness among all stakeholders about each other’s roles and belonging, interests, and (non)power. Ultimately, it helps them to understand each other better.

Furthermore, we observed stakeholders making combinations of online and offline usage of the Canvas. For instance, some people organized offline conversations and discussions, and also applied the Canvas on online tools such as Miro to document findings, make summaries and share or exchange these with one another after offline usages.

Recommendations

Moreover, we learned that stakeholders appreciate the Canvas stimulating to embed visualizations more, because otherwise the Canvas can become relatively textual. In the context card, it might be productive to ask for examples and narratives of problematic situations, how they are encountered, and to what dilemmas they lead. Next, the impact can be visualized in a metaphor, for example.

In the stakeholder card, the coalition as a collective is not yet explicitly considered. In our safety project, a column was added which aims to discuss common interests, shared knowledge, and typical power (this relates to the purpose card) in order to be clear who’s interest, knowledge, and power is missing in the commoning.

In the activity card, the iterative aspect of design (series of diverging and converging) could be added and the accompanying design phases and synthesis such as explore-reframe-create-envision-evaluate-conclude (Smeenk & Willenborg, 2017, 2022).

The guiding questions on each Canvas card are optional and depend on the context and people, spheres of life, disciplines and domains involved. In our safety project, we tweaked them towards the specific domain and its accompanying vocabulary. We found for example that experimenting as a term does not have a positive connotation in safety processes while an experimental project is accepted as term.

Since we can work in-situ again, we have been using the Canvas in different sizes then the A1 format developed before. We for example printed a 3 by 4 meters carpet of the Canvas which really adds to the playfulness, see Figure 5. Stakeholders can stick real sticky notes on the Canvas, draw and build on it and navigate through it while literally standing on the topics or elements that need to be considered.

Figure 5. The empathic Co-Design Canvas as a carpet in the wild.

All above suggestions still need more experimentation, testing and evaluation. Some recommendations might also make the Canvas too complicated. Less can be more. Therefore, we will continue using the Canvas and searching for balance in all the ideas given above. The main question that pops up often seems to be how to make stakeholders use the Canvas for a longer period of time as a dynamic growing document. And when do we discard the Canvas? Last but not least, a stakeholder advises us not to use the Canvas if an urgent challenge needs action today.

Conclusion and Future Work

This paper provides a novel, evaluated, practical, and playful instrument and model for empathic co-design processes in dynamic, multi-stakeholder, and systemic contexts: the empathic Co-Design Canvas (Figure 3) and framework (Figure 4). The Canvas’ theoretical underpinning (Lee et al., 2018), evaluation in and initial development with practice (Smeenk et al., 2021) has certain rigor. Moreover, this so-called intermediate-level knowledge product (Höök & Löwgren, 2012) demonstrated that people are willing to start with this new way of working. This -by now ongoing- project commutes from theory to practice and back again. The adjusted framework in Figure 4 shows that. Herewith, I also contribute to the ongoing discussion of the role of design practice in academic research (Gaver & Bowers, 2012; Löwgren, 2013; Stolterman, 2008).

The Canvas is well grounded due to the work of Lee et al. (2018) and more appealing to designers and practice due to the empirical work. This intermediate-level knowledge product represents the knowledge of Lee et al. (2018) in an appropriate familiar medium to practice and now accommodates the nature of co-design practice without undue scientistic reduction (Höök & Löwgren, 2012; Löwgren 2013). Besides, the Canvas transcends specific design methods (Woolrych et al., 2011) as a boundary object or convivial tool (Star, 1989; Sanders & Stappers, 2012). Herewith it delivers goal-oriented knowledge (Van Turnhout et al., 2019). Moreover, the overview the Canvas brings can show practice how systems’ structures hang together, how they might move along, and how stakeholders may or may not be able to direct the system (Stappers, 2021). Herewith it will facilitate and promote coalitions to be flexible and adaptive in their approach of a dynamic problematic situation, clear about their common purpose, its systems’ elements and their interrelations.

The Canvas expands on the original framework of Lee et al. (2018) in three ways. First, it can be used beyond co-creation projects. We observed that the Canvas qualifies in systemic societal challenge settings where multi-stakeholders collaborate in value networks towards multi-value creation (Brand & Rocchi, 2011; Smeenk, 2021, 2022). Second, the Canvas is not merely accessible to researchers. It is a user-friendly intermediate-level knowledge product for all stakeholders involved (Höök & Löwgren, 2012). Through its accessible form, vocabulary (Gaver & Bowers, 2012), and the accompanying Manual, the Canvas is easy to use in practice by stakeholders (including non-designers) in flexibly planning, commonly conducting, and deliberately reflecting in and on a co-design process. Third, it can provide for new research questions and theoretical knowledge.

In future work, I want to explore whether, and if so, how the Canvas can inform and inspire the Mixed Perspectives methodology (Smeenk et al., 2016) and vice versa, and our Empathic Formation compass thinking (Smeenk et al., 2019), for example, by explicating how the Canvas can include stakeholders’ first, second and third-person perspectives. Both frameworks are initially developed for individual designers but might be suitable for individual and collective use by multi-stakeholder teams including non-designers. I also think of integrating these ways of thinking and working in something we call Systemic Co-Design, www.systemischcodesign.nl/en.

Finally, I do not see the Canvas as a static tool. Importantly, just as Lee et al. (2018) argue that the current co-design decision set might not cover all possible co-design decisions, the Canvas’ topics or elements might not be exhaustive as well. I, therefore, expect them to evolve and expand as our or others’ experiences with the set and the Canvas evolve and develop (that is also why post-case study experiences with the Canvas are included in this article). It might be due to changes over time, as our dynamic research community might identify other design principles, decisions, and activities important to societal challenges. This might inspire or require a revision of the framework and Canvas. Design decision cards can then be added, or existing ones can be expanded with subcategories, etc. Others are explicitly invited to join us in this powerful journey.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program under grant agreement No. 788217. We would like to thank all the citizens, policy makers and the Cube design museum project manager and researcher Anja Köppchen, and strategist Gene Bertrand for their trust in the process and sharing their experiences and giving honest reflections on the processes to support the development of the empathic Co-Design Canvas.

References

- Abson, D. J., Fischer, J., Leventon, J., Newig, J., Schomerus, T., Vilsmaier, U., & Lang, D. J. (2017). Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio, 46(1), 30-39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216-224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Brand, R., & Rocchi, S. (2011). Rethinking value in a changing landscape. Philips. http://www.rickdevisser.com/assets/economic-paradigms-paper.pdf

- Cash, P., Daalhuizen, J., & Hay, L. (2022). Editorial: Design research quality. Design Studies, 78, 101079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2021.101079

- Carlile, P. R. (2002). A pragmatic view of knowledge and boundaries: Boundary objects in new product development. Organization Science, 13(4), 442-455. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.4.442.2953

- Chen, D. S., Cheng, L. L., Hummels, C., & Koskinen, I. (2016). Social design: An introduction. International Journal of Design, 10(1), 1-5.

- Cockton, G. (2013). Design isn’t a shape and it hasn’t got a centre: Thinking big about post-centric interaction design. In Proceedings of the international conference on multimedia, interaction, design and innovation (Article No. 2). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2500342.2500344

- Colusso, L., Jones, R., Munson, S. A., & Hsieh, G. (2019). A translational science model for HCI. In Proceedings of the conference on human factors in computing systems (Paper No. 1). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300231

- Design Council. (2021). Beyond net zero: A systemic design approach. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/fileadmin/uploads/dc/Documents/Beyond%2520Net%2520Zero%2520-%2520A%2520Systemic%2520Design%2520Approach.pdf

- Dorst, K. (2010). The nature of design thinking. In Proceedings of design thinking research symposium (pp. 131-1391). DAB Documents.

- Fulton Suri, J. (2003). Empathic design: Informed and inspired by other people’s experience. In I. Koskinen, T. Mattelmäki, K. Battarbee (Eds.), Empathic design: User experience in product design (pp. 51-58). IT Press.

- Gardien, P., Djajadiningrat, T., Hummels, C., & Brombacher, A. (2014). Changing your hammer: The implications of paradigmatic innovation for design practice. International Journal of Design, 8(2), 119-139.

- Gaver, B., & Bowers, J. (2012). Annotated portfolios.

Interactions, 19(4), 40-49. https://doi.org/10.1145/