A Study of Dignity as a Principle of Service Design

Miso Kim

Department of Art+Design, College of Arts Media and Design, Northeastern University, Boston, USA

This paper upholds the premise that dignity is a fundamental principle of human-centered design. I argue that consideration of dignity is particularly important in service design, as service concerns the collective participation of people with diverse backgrounds and needs. Service often starts with situations in which strangers meet for the first time and must collaborate to co-produce a service, which can sometimes lead to conflicts. This paper explores four perspectives of dignity that are grounded in utilitarian, humanistic, individual, and collective bases: dignity as merit, autonomy, universal rights, and interpersonal care. Key philosophical interpretations, social backgrounds, and historical shifts related to the concept of dignity are introduced, with design examples that reflect each of its dimensions. I then present research questions based on each concept of dignity and propose a research agenda to utilize the pluralistic framework of dignity in service design.

Keywords – Service Design, Dignity, Design Principle, Design Ethics, Design Philosophy.

Relevance to Design Practice – This paper studies the concept of dignity as a principle of service design. This pluralistic framework of dignity can elicit productive discussions regarding the nature of service design and its role in societies, conflict resolution, the development of methods and tools, and the exploration of principles and ethics.

Citation: Kim, M. (2021). A study of dignity as a principle of service design. International Journal of Design, 15(3), 87-100.

Received Nov. 1, 2020; Accepted Oct. 30, 2021; Published Dec. 31, 2021.

Copyright: © 2021 Kim. Copyright for this article is retained by the author, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: m.kim@northeastern.edu

Miso Kim is an assistant professor and the program head of Experience Design MFA/MS/certificate in the Department of Art+Design at Northeastern University. She is also the design director of the NuLawLab, the interdisciplinary innovation laboratory at Northeastern University School of Law. She received a PhD in Design, an MDes in Interaction Design, and an MDes in Communication Planning and Information Design from the School of Design at Carnegie Mellon University. Prior to joining Northeastern, she worked as a Senior User Experience Designer at Cisco Systems in Silicon Valley. Her research explores the humanist framework of service design, with a focus on dignity, autonomy, and participation. She has published in key journals and conferences including Design Issues, the Design Journal, the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), Design Research Society International Conference (DRS), and the International Association of Societies of Design Research World Conference (IASDR).

Introduction

The United Airlines Flight 3411 incident in 2017 revealed that even highly sophisticated services, such as modern air travel, still lack consideration of fundamental principles such as dignity. When Dr. David Dao refused to give up his seat on the overbooked flight, he was forcibly dragged off through the plane’s corridor like a piece of luggage. Shocked passengers uploaded videos of the scene to social media, which caused outrage among the wider public. United Airline’s CEO provided multiple excuses, but the company’s stock price still dropped by $255 million, and a congressional hearing was held (Bendix, 2017; Kottasova, 2017). Dr. Dao described this incident as more horrifying than his experiences during the Fall of Saigon (White, 2017). When asked what his injuries were, he responded, “Everything” (Grinberg & Yan, 2017). Around this time, United had been going through a procedural redesign to enhance their services. Their app, webpage, lounge space, in-flight food packaging, and even napkins had been updated with a more contemporary aesthetic. However, I propose that this incident demonstrated that service design is more than an array of products; a service is a human system that supports the collaboration of multiple stakeholders, including customers, workers, and the wider community of people who are directly and indirectly involved (Kim, 2018a; 2018b).

The number of reports about service controversies that have been discussed in relation to dignity have increased exponentially over the last 10 years. Continuing with flight services, examples include teen girls being prevented from boarding flights because they wore leggings (Lazo, 2017), overweight customers not being able to request extra extensions for their seatbelts (Wray, 2020), and a mother with babies in her arms being yelled at while looking for a space to put a collapsible stroller (Steinbuch, 2017). On the other hand, airlines are also understaffed, and the flight attendants are under stress to perform the dual role of care and safety (Kelleher & McGilloway, 2005), making high-pressure decisions that are classified as intense emotional labor (Hochschild, 1983). Sometimes flight attendants are even required to follow regulations regarding appearance and behavior reflecting stereotypical gendered attributes (McDowell, 2011). At the same time, there are increasing cases of verbal or physical attacks by passengers (McCurry, 2016; Gibson, 2021). These incidents show that dignity is equally relevant from both customers’ and workers’ perspectives.

Meanwhile, the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic has revealed how much we rely on services to connect us with others. From services as basic as having toilet paper delivered to more complex ones like taking a COVID-19 vaccine, many people’s day-to-day lives are interwoven with services. Simultaneously, the pandemic has highlighted that a service can be a battleground of principles. For example, the tension surrounding the requirement to wear masks has escalated into insults and violence in public transportation, theme parks, airports, restaurants, and grocery stores (Anglesey, 2021; Goldbaum, 2020; Kim, 2021; Porterfield, 2020). Customers who refuse to wear masks have argued that the regulations compromise their dignity. From a service provider’s perspective, mandating masks protects the dignity of other customers. Simultaneously, service workers have been placed in a position where their dignity is directly threatened by being exposed to assaults. With social distancing guidelines in place, service co-productions are almost the only occasion in modern life that requires strangers to collaborate, which can sometimes lead to conflicts.

These examples suggest there is a need to study moral principles when designing services. Aristotle (n.d./1998) defined a principle, which he called archē, as “the first basis from which a thing is known,” or the originating source for actions (p. 114). A moral principle is a foundation of conduct that involves human decisions about rightness and serves as a basis for ethical applications (Hare, 1991). Specifically, morality involves “supreme end or good, and a number of rules which can be said either to express the nature of this end, or to provide or suggest the means of its realization.” (Allan, 1953, p. 120). This resonates with Ylirisku and Arvola’s (2018) argument that the different design approaches are grounded in different appreciations of goodness and that more precise understanding of such values can improve design processes and critiques. Discussing the principles behind decisions can help people to discover commonalities and differences, thereby assisting in solving a shared problem. McKeon (1990) suggested that principles can sublimate opposition by orienting the parties toward understanding the reasons for controversies, thereby serving as the basis for agreements and pluralistic applications of policies.

In this paper, I explore the concept of dignity as a foundational moral principle. Dignity is an abstract concept with many definitions, but scholars commonly indicate that dignity can be roughly framed as the fundamental value of a human. For example, in Dignity: A History, philosophy scholar Remy Debes (2017) observes that dignity is defined today as “fundamental moral worth or status supposedly belong[ing] to all persons equally” (p. 1). Bioethics scholar Rosemarie Rizzo Parse (2010) defined dignity as “a state, inherent respect, worthy of honor, high regard” (p. 257), while international conflict expert Donna Hicks (2011) described dignity as a notion that “human beings are imbued with value and worth” (p. 2). Resting upon the principal assumption that humans have end value by themselves (Kant, 1785/1998), dignity serves as the first basis for important moral principles of human societies. For example, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948) starts with a statement that construes dignity as a foundational principle: “(T)he inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world…” (p. 1). The study of dignity and related philosophy regarding the fundamental value of human beings is especially relevant to service design. As Carlsson (2013) proposes, service design deals with social norms at multiple levels, placing designers in a position to engage with conflicting values while serving as advocates of the stakeholders. The perspective of dignity promotes the understanding to view humans as agents who actively govern their own lives and utilize services to enhance them, rather than as cogs in a labor force, components of a market segment, or consumers who passively use up the value at the end of the supply chain.

Although scholars have explored the significance of dignity as a principle of design (Buchanan, 2001; Kim, 2018b), there is a general lack of study in the field about the concept of dignity in and of itself. Dignity is a paradoxical concept that reveals the tensions between contradictory, coexisting values (De Wit & Meyer, 2009) that have emerged throughout human history. Dignity is inborn yet acquired (Mckeon, 1990), universal yet comparative (Debes, 2017), personal yet social (Shell, 2008), and rational yet emotional (Hicks, 2011). In the present paper, I study the meanings of dignity through multiple perspectives to provide a common language and a framework for designers, collaborators, and stakeholders. In the following sections, I first examine principles related to design and service design to distill the four points of the axis for theorizing a design principle: utilitarian, humanistic, individual, and collective bases. With these bases, I propose a framework with four concepts of dignity: merit, autonomy, universal rights, and interpersonal care. Key philosophical discussions regarding each aspect of dignity will be introduced with design examples, followed by research questions and strategies to nurture service design with dignity.

Background

Principles in Design: Utilitarian and Humanistic Bases

The term principle has been appropriated in different contexts within the field of design. First, it often relates to how strategies are operationalized in methods or practices. For example, Dieter Rams (2009)’ ten principles for good design or Don Norman (2013)’s seven fundamental design principles indicate practical rules that are directly applicable to the composition of a product. Designers frame patterns of solutions to respond to a complex design problem using their experience, applying them as a working principle (Dorst & Dijkhuis, 1995).

Principle also indicates what are the fundamental truths underlying these practical rules. Often driven from the existing nature of things, these principles can be empirical laws for scientists, like Newton’s laws of motion. In such cases, principles provide the foundations upon which hypotheses rest. In design, maxims like form follows function (Sullivan, 1896) embody the principle of functionalism, which was considered a fundamental truth in the Modernist era. Design histories present principles through exploration of the nature of design. For example, Pevsner (1936) proposed design as the art of an epoch that expresses the principle of beauty and, thus, the ideology of the era. Heskett (1980) approached design as the development of new materials and technologies to achieve the principle of efficiency. Forty (1995) argued that design embodies myth in the form of products that influence the desires and lives of customers, operating according to the principle of rhetorical persuasion.

While the previous two interpretations of principles emphasize the utilitarian value of design, there is another view that emphasizes the humanistic value of design: principle implies moral values regarding why people should behave or be treated in certain ways. For example, Plato referred to value-laden virtues as the ideas (ἰδέα) that encapsulate the essential principles of the world. Furthermore, Dewey (1891) proposed that a principle is a grounding assumption based on which people make moral decisions when interacting with problematic situations. From a design perspective, principles serve as hypotheses with positive moral values that provide a framework for designers and those who use products and services. These moral principles influence the plurality of arguments that are embedded in the design outcome (Jafarinaimi, 2011). Buchanan (2019) also suggested that principles are the beginning and end of inquiry, helping designers to define problems, guiding the design process, and providing moral criteria for evaluation.

Additionally, Buchanan (2001) proposed dignity as the first principle of design on which our work is ultimately grounded and justified. According to Buchanan, design is grounded in dignity, as design conceptualization places humanity at the center. Simultaneously, design is an essential instrument for embodying dignity in our everyday lives. Design is a practical discipline of responsible action that brings dignity into concrete reality, inculcating the abstract concept of dignity into tools that enable people to enhance their lives. Indeed, human-centered design is “an ongoing search for what can be done to support and strengthen the dignity of human beings” (Buchanan, 2001, p. 37). This foundational paper highlighted the significance of dignity in design, but there is a further need to investigate the meaning of dignity and thereby to make a connection to practice, as there is a lack of design scholarship that explores the concept of dignity in depth. In this paper, I study the multiplicity of meanings that have been associated with the term dignity and how this principle can advance service design; Dignity is especially important in this area where the focus of design shifts from the materiality of products to human decisions, actions, and the collective experiences of people who use and co-create services.

Principles in Service Design: Individual and Collective Bases

As in the general field of design, the principles discussed in service design include utilitarian and humanistic value. The term principle is most frequently used in service design to refer to practical methods and strategies; for example, five behavioral principles and principles of human behavior and interaction are considered ways to increase productivity in service delivery (Chase & Dasu, 2001; Karwan & Markland, 2006). Many practical principles aim for operational efficiency and effectiveness, which can be traced back to the management and marketing foundations of the field. For example, Levitt (1972), one of the first scholars who argued for the need to design services, emphasized a mass-production approach to save costs. In this tradition, service design is often seen as a means of control that channels the behavior and choices of workers and customers to maximize production.

In contrast, Karpen et al. (2017) proposed six principles of service design based on research on the nature of design: human- and meaning-centered, co-creative and inclusive, transformative and betterment-oriented, emergent and experimental, explicative and experientially explicit, and holistic and contextual. These principles reveal that the essential characteristic of service design is a humanistic approach, which differentiates the contribution of design in the development of service from the traditional utilitarian focus.

First, humanizing services has been considered a core competency of designers. Service design emphasizes customer-centric experiences (Holmlid & Evenson, 2008; Stickdorn & Schneider, 2011), which aligns with the larger shift in service research from transactional value to value-in-use and context (Vargo & Lusch, 2008). The concept of meaning plays a key role in human-centered design, especially in the shift of design’s focus from function to human agency (Krippendorff, 2008). Meaning-making by the stakeholders is crucial in value co-creation and resource integration (Korper et al., 2021). Services gain meaning when they are situated in customers’ everyday experiences and as a totality instead of a series of individual service offerings (Goldstein et al., 2002). A multilevel approach is needed to develop a holistic system that supports various human needs (Patrício et al., 2011). Therefore, the principle of human- and meaning-centeredness is closely tied to the principle of wholeness and contextuality proposed by Karpen et al, emphasizing designers’ ability to orchestrate a comprehensive service system.

Second, service design is existentially participatory. Participation is crucial in service not only as a method in the process, but also as a performance in the outcome. A service is co-produced on the spot through the collaboration of stakeholders. These active participants bring their resources and skills into the service encounter (Sangiorgi & Clark, 2004). Therefore, service design seeks to systematically support co-production and optimal conditions for value co-creation with customers (Kimbell, 2011; Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011). In this process, designers serve as interpreters who bridge the gap between the designed system and the stakeholders (Wetter-Edman, 2014). The explicative and explicit nature of service design is utilized to ensure customers’ participation by providing them with tangible touchpoints. For example, designers provide a concrete and controllable (Miettinen & Koivisto, 2009) action platform (Manzini, 2011) that enables multiple interactions for the participants.

Last, service design is transformative. The explicative and experiential nature of service design supports design’s inherently transformative nature. As drivers of organizational change and innovation, designers collaborate to create services that can achieve lasting change and benefit organizations in the long run (Junginger & Sangiorgi, 2009). Moving beyond the organization, the transition design movement aims to expand service design to accommodate a “design-led societal transition toward more sustainable futures” (Irwin, 2015, p. 229). These approaches align with recent transformative service research that seeks societal well-being in addition to economic value (Anderson et al., 2013). Service design and research for the common good are rapidly growing and emphasize equal access to resources, belonging, self-esteem, fairness, and sustainability as key aspects of services in communities (Cook et al., 2002; Junginger & Sangiorgi, 2009).

The principles above all emphasize service design’s focus on the collective. Broadly construed, design principles often focus on an individual user’s interaction with a product or a designer’s decision-making. Service design, however, creates a system that supports the collective action of multiple stakeholders. Just as design processes require guiding principles, the services co-produced by stakeholders through touchpoints need foundational frameworks. In service design, therefore, principles influence not only design activity but also the stakeholders’ value co-creation and, in the long term, service maintenance and redesign. Therefore, service design needs to consider social norms and moral principles that will guide the interactions among multiple players in addition to the principles of economic and engineering efficiency.

This paper studies dignity to further highlight this humanistic and holistic nature of service design. Dignity can serve as a guiding principle that supports moral judgements in the process of design and co-production as well as provide the groundwork for the what and how of service design. Additionally, the philosophical understanding of the fundamental value of human beings will lay a foundation for other moral principles, such as equity and freedom.

Dignity in Design and Service Design

In design literature, the word dignity can be found in the context of designing for vulnerable populations. It is broadly described as attention to basic or sensitive needs and is often coupled with keywords such as empowerment, security, comfort, privacy, justice, intimacy, trust, empowerment, and compassion. Projects in which dignity is considered include public spaces for older adults (Sarre, 2007), furniture for bariatric patients (Williams, 2008), technology for homeless populations (Le Dantec & Edwards, 2008), hospital architecture (Clarke, 2009), and empathy tools for medical devices (Hosking et al., 2015).

Moreover, in the situations described in the current scholarship, dignity is frequently associated with people who are excluded from mass-produced designs. In this sense, dignity is indirectly related to design approaches that respect human diversity, such as accessible design, value-sensitive design, and inclusive design (Clarkson et al., 2013; Friedman, 1996; Lebovich, 1993). Additionally, the user’s sense of dignity is mentioned as one of the key themes of compassionate design (Seshadri et al., 2019). However, there is a general lack of research investigating the meanings, history, and conceptual framework of dignity as a principle of design. Basic descriptions of dignity are offered as means of characterizing problems, but the philosophical nature of dignity has been undertheorized.

In service design, dignity is often mentioned in medical services, such as child obesity programs (Foley, 2018) and experiences in sensory modulation rooms (Barbic et al., 2019). It is also considered in public services, such as in the experience of justice in a courthouse (Rowden & Jones, 2018), shelter-based healthcare facilities for the homeless (McNeil & Guirguis-Younger, 2014), and humanizing technology in healthcare (Hosking et al., 2015). Transformative service research seeks to promote dignity as a public good (Alkire et al., 2019), and protecting and promoting human dignity is one of the key desired outcomes of social innovation in service (Kabadayi et al., 2019). In service innovation, the dignity of participants is an ethical consideration that serves as an important guideline in the evaluation stage (Sudbury-Riley et al., 2020).

Even the term dignity is not directly mentioned, in the cases that designers have increasingly pursued social innovation and designed for those who have been excluded from traditional service systems. For example, service inclusion has been identified as necessary for “an egalitarian system that provides customers with fair access to a service, fair treatment during a service and fair opportunity to exit a service” (Fisk et al., 2018, p. 835). In addition, transformative social marketing argues that design can play an important role in honoring people and values such as dignity (Lefebvre, 2012). The present paper seeks to support and enrich these efforts by providing a systematic and theoretical framework of dignity.

Toward a Conceptual Framework of Dignity Based on Four Perspectives

Dignity is a complex and multi-faceted concept, encompassing one’s image of the self in relation to one’s treatment by others. According to Waldron and Dan-Cohen (2012), honor and worth are the two universally understood components of dignity as fundamental human value. Honor is an extrinsic value with a social origin, shifting depending upon one’s function, status, and rank in a society. In contrast, worth indicates an intrinsic and absolute value with which all humans are born. Another word that is often used in defining dignity is respectful treatment (Fuller & Gerloff, 2008; Margalit, 1998; Macklin, 2003; Parse, 2010). Being respected means that a person is not only widely-known for their accomplishments but also excels in a way that befits the virtue of their society. In other words, dignity is a value that is dependent on the agreement of the societies to which the individual belongs, assuming a harmonious relationship between an individual and others who appreciate the value of the individual and provide a respectful treatment.

The focus of these social relationships has shifted throughout history. Most scholars have traced the modern concept of intrinsic universal human value back to 1945 with the Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations (Debes, 2017; Rosen, 2012; Waldron & Dan-Cohen, 2012). However, dignity antedates this by thousands of years, originating in the Roman concept of dignitas, or the honor-based status of an individual within a hierarchical society. There are different hypotheses about the relationship between dignitas and universal rights. Some scholars have implied that dignitas evolved into autonomy and then into human rights (Debes, 2017). Others have proposed that universal rights already existed within the complicated and multifaceted concept of dignitas and were only later discovered (Griffin, 2017). It has also been theorized that dignity was universalized as human rights during the century of revolution, unrelated to dignitas (LaVaque-Manty, 2017). Another influential perspective is the expanding circle view, which suggests that we are still living with a merit-based concept of dignity, but the boundary of the social elite has been expanded to include everyone (Waldron & Dan-Cohen, 2012). I propose that pluralistic interpretations of dignity have always coexisted throughout history and in today’s society.

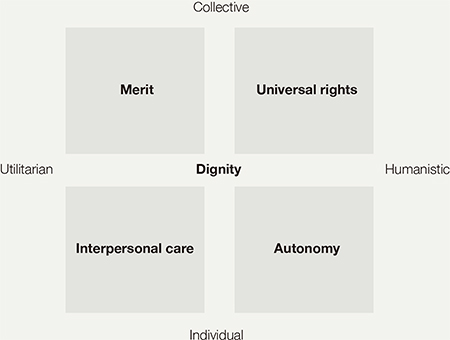

In the Background section, I suggested that design principles generally emphasize the utilitarian and the humanistic perspective, while service design principles highlight the individual and the collective. I use these four bases to propose a pluralistic framework that organizes the four key concepts of dignity that have emerged through history (see Figure 1). I argue that the utilitarian base emphasizes valuing people for their ability to achieve certain goals for a group. In contrast, I define the humanistic base as appreciation and pursuit of human fulfillment as a value itself. The individual base assumes that human value originates from each person’s decisions, actions, emotions, or their relationships with other individuals. The collective base, in comparison, is a perspective that stresses the role of the social system in bestowing and securing the human values of its members. First, I suggest that dignity is synonymous with merit, a concept grounded in the utilitarian and collective bases. Second, I present dignity as autonomy, a humanistic and individual value. Third, I analyze dignity as universal rights with humanistic and collective foci. Finally, I conceptualize utilitarian and individual dignity from the perspective of interpersonal care. In the following section, I present how the existing philosophical discussions of dignity can be organized based on this framework.

Figure 1. Four perspectives on dignity.

Merit

One of the oldest and most conventional understandings of dignity is the utilitarian value of an individual based on their usefulness in society. Everyone within a group has a designated position according to their qualifications, and dignity is based on a person’s market value (Hobbes, 1651/1904). This view, understanding humans as the functional components of a group, can be typically found in ancient hierarchal societies.

The Latin word dignitas, which is the root of dignity, referred to a comparative, earned value. Dignitas was a highly public concept related to the notion of honored status. People had more dignitas if they were better suited for a higher rank, either by possessing more power or fulfilling more societal duties (Gordis, 1905). Therefore, it was closely related to public service, an individual’s role and rank, and a manner that befitted such positions. Dignitas could be threatened or lost as a result of public condemnation. Roman stoics like Cicero and Seneca implied that, although all humans have innate value and deserve to be helped, their social value differs based on their inclusion in communities and meritocratic value. They argued that fairness comprises benefits being first given to those who served their community with more dignitas (Griffin, 2017).

This utilitarian and collective understanding of dignity prevailed into the Middle Ages, when the world was seen as a hierarchical chain of being progressing downward from God to angels and then to princes, nobles, commoners, animals, plants, and minerals. The myths of the creation, fall, and redemption proposed that dignity was given by God but had been lost due to the original sin, and to regain it, people had to contribute to the Church (Kent, 2017). This comparative conceptualization of dignity based on rank and merit has continued throughout history (Darwell, 2017; Rosen, 2012) and remains one of the key components of dignity today.

In design, a meritocratic understanding of dignity is a main strategy for designing luxury-brand goods or services. For example, higher cost and classism play as a proxy for the brand and the customer’s worth. Therefore, differentiation and exclusivity have often been intentionally designed in services to make the customer feel more special than others. For example, in the Victorian era, chairs for servants, which were placed next to the main entrance to greet guests, were elegantly decorated but had no cushion and a stiff back (Forty, 1995). This was intended to degrade the servant while remaining attractive; thus, the furniture functioned as a prop to highlight the comparative dignity of the houseowner. Today, supermarket cashiers are often prohibited from sitting on chairs while they work at the checkout counter to express respect for the customers. Furthermore, the principle of differentiation is often implemented on airplanes, where the services provided to customers are strictly based on how much a customer pays for their ticket. For example, Japan Airlines’ flight attendants provide kneeling service when attending to customers in first class (MinNews, n.d.). The 2008 Korean Air advertisement features the kneeling image of a flight attendant with the phrase “From departure to arrival, only dignified services for our dignified guests” (Lapinski, 2008).

Autonomy

A contrasting understanding of dignity arises from the humanistic and individual bases. Modern philosophers have argued that human dignity is an intrinsic value originating from our nature, rather than an extrinsic value bestowed by a collective authority, such as the state or the church. For example, Pico Della Mirandola (1486/1996) identified the basis of dignity in our freedom of choice and becoming. As one of the most representative humanist philosophers in the Italian Renaissance, he proposed that humans have the simultaneous potential to become angels and animals. He argued that the dignity of a human is less about the outcome but the choice–that the individual has the potential and freedom to choose what they want to become.

Other scholars have theorized that individuals’ dignity is founded on reason and free will (Rosen, 2012). For example, Kant (1785/1998) argued that humans have end value because we have the capacity to set up moral rules and act in accordance with our inner will instead of serving external causes. Moral rules have an end value that cannot be compared or exchanged. Therefore, humans with pure reason, from which these moral rules originate, have end value, or dignity. This view is sharply contrasted with merit, according to which rules are created by the community and imposed on members. However, autonomy assumes that the moral rules created by individuals should align with universal ethics, and the individual should treat themself and other human beings equally. Therefore, autonomy connects self and others by relating esteem and respect, or in Nietzsche’s words, sublimating freedom (self-love) and law (self-respect) into self-responsibility (Shell, 2008, Gemes and May, 2009).

Kant’s concept of autonomy is considered one of the most profound philosophies about dignity, providing the foundation on which dignity has been related to human rights since the Age of Enlightenment. Scholars have argued that human rights are conditions for exercising normative agency (Griffin, 2008). Today, dignity as autonomy serves as a key principle in many arenas where attention to dignity is especially needed, such as the field of medical ethics, which strives to ensure patients are protected and can make informed decisions about their own bodies. One of the most cited definitions of dignity in medical ethics is “dignity means no more than respect for persons or their autonomy” (Macklin, 2003, p. 1419). This emphasis on dignity as autonomy led to the establishment of the Institutional Review Board for Protection of Human Subjects in Research (IRB), which provides guidelines to protect subjects’ autonomy through voluntary consent. The IRB protocol is one example of how the principle of dignity can be applied to design research.

Another design example incorporating the principle of dignity as autonomy is IKEA’s ThisAbles campaign in 2019, developed in collaboration with two non-profit organizations: Access Israel and MILBAT. ThisAbles is a system that allows the user to personalize the company’s furniture so that it is accessible to those with special needs. The introductory video starts with the story of Eldar, who has cerebral palsy. Eldar describes that with the help of the couch lift feature, he no longer fears not being able to get up from a regular sofa. Although the feature is just a simple plastic component placed under the couch legs to lift it up higher, it provides options to increase accessibility and support the autonomy of users. ThisAbles has turned IKEA products into a service by respecting the autonomy of customers, from its Hackathon event in which disabled customers were invited to participate in the co-design of ThisAbles to the versatile nature of its products, some of which can even be manufactured at home via a 3D printer (see ThisAbles website, https://thisables.com).

Universal Rights

Broadly construed, dignity is commonly interpreted as universal rights in today’s democratic societies. For example, Article 1 of the 1949 German Constitution states, “Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority” (Constituteproject.org, 1949/2014, p. 8). Here, dignity emerges as an intrinsic and inalienable right of everyone based on a peaceful community and just society (Rosen, 2012). It focuses on humanity overall, without a hierarchy, and humans are seen as ends in themselves (Rao, 2011; Spiegelberg, 1971). In comparison to autonomy as an individual capacity, universal rights focus on creating a system that equally distributes resources for all humans and protects them from threats to the basic conditions, such as safety and privacy.

Notably, universal rights are a political construct. An inchoate notion of shared dignity for members of the same culture or faith was proposed by ancient philosophies (Griffin, 2017) and medieval theologies (Kent, 2017). However, it was not until the Enlightenment, during which citizens’ natural rights were discussed, that the notion of universal and equal rights emerged. This conception evolved throughout the revolutions and labor movements of the nineteenth century, the World Wars, and the civil rights movement of the twentieth century (LaVaque-Manty, 2017). Legal systems followed these civil movements, as it was perceived that people needed protection by the state from violations of their dignity (Gewirth, 1984; McCrudden, 2008).

Dignity as a universal right has been discussed, agreed upon, and re-defined by people, and its boundaries are continuously expanding. Reviewing the discussions of the committee that prepared the declaration of human rights, McKeon (1990) proposed that the concept of dignity evolved from civil and political rights to economic and social rights and then to cultural rights. The 17th- and 18th-century debates were focused on personal rights, such as freedom of belief and assembly against monarchies. After legal systems were created to protect these rights, the debates expanded to include ownership, labor, and the use of public resources, such as education and healthcare services. McKeon argued that the next phase included cultural rights of inquiry, expression, and communication.

An example of how design reflects an increasingly inclusive understanding of universal dignity is the segregated seating within the US public transit systems during the mid-20th century. Although all seats were ergonomically the same, the service design limited their usage, reflecting the socially accepted sense of dignity at that time. In 1955, bus drivers in Montgomery, Alabama were required to provide separate seating assignments for black and white passengers. This was enforced by a sign placed in the middle of the bus, which regulated black passengers to sit in the back of the bus. As the bus continued to fill with white passengers, the bus driver moved the sign back one row and asked the four black passengers sitting in that row to give up their seats. Among these passengers was Rosa Parks, who refused to relinquish her seat, so the driver called the police to arrest her. This incident led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which compelled the Supreme Court to convene and eventually declare that segregation on public transit is unconstitutional (see https://www.biography.com/activist/rosa-parks). Today, the seating design on US public transit reflects the principle of equal, universal dignity.

Interpersonal Care

Another aspect of dignity that permeates our everyday lives can be found in person-to-person interactions: dignity as respectful treatment from one individual to another. This perspective focuses on individual and utilitarian value, emphasizing communication as a means of avoiding conflict and practical problem-solving for mutual interest. Dignity exists in the interpersonal treatment of individuals based on social emotions, such as empathy, care, and respect. Scholars like Diderot argued that emotion is at the core of humanity and dignity (as cited in Debes, 2017). Oftentimes, this view establishes dignity in an individual’s psychological instinct to maintain connections with other individuals. For example, Hicks (2011) argued that dignity is a feeling and biological instinct, proposing that the essence of humanness is empathy, which is crucial for forming relationships with other humans and surviving as a group. A sense of dignity, or how others value an individual, is hard-wired in our limbic brain. Humans are social beings that are biologically inclined to react to feelings of humiliation as intensely as they do to physical threats because dignity is a sign of the groups we belong to valuing or rejecting us. Therefore, dignity is a deeply emotional issue and a utilitarian key to resolving social conflict. Hicks proposed that it is an individual’s responsibility to realize that certain expressions can hurt others and to control such communications.

Kim’s (2015) interpretation of hospitality also enriches the understanding of dignity as interpersonal care. Kim argued that what makes a human is other humans; people become human by entering a society and being greeted by other people, and humanness is a status qualified by the conferring of hospitality, or respectful treatment by others in everyday life. It is a ritual to confirm one’s belonging to the human community. Therefore, dignity is recreated through the everyday ritual of the treatment we receive from others. This argument resonates with Margalit’s (1998) concept of a decent society as one that does not humiliate its members and possesses the proper conditions for individuals to treat each other with respect.

From a service perspective, designers have paid attention to the importance of performance and rituals as a way to express hospitality. Service rituals such as offering a chair for someone waiting help to define the situation, so that even a newcomer can feel welcomed and comfortably adjust to the service environment. Convention-based elements of service design, such as scripts and uniforms, further help define the roles of the stakeholders and respectful interactions in service performance. Often, issues with dignity arise when these expected conventions are broken. However, dignity as interpersonal care also implies true attention beyond performance. Various customer reviews demonstrate that people are moved by small acts of hospitality by service providers, such as preparing a baby chair in a restaurant or recognizing that chair legs are wobbly and need to be fixed. Often, when service providers exhibit special attention to customers’ needs by catering to their personal preferences, customers perceive the service provider as another human being, thus making the service experience memorable. Interpersonal care can also include interactions between customers. For example, seating areas on public transit that are reserved for passengers with physical disabilities encourage other passengers to offer their seats to those who need assistance.

Discussion

In the previous section, I reviewed the diverse conceptualizations of dignity that have coexisted throughout history. Although the comparative assessment of an individual’s value was prominent in the ancient world, there were also philosophical discussions about the inherent value of mankind. Modern constitutions, covenants, and declarations were founded to protect the universal dignity of human beings, but merit-based understandings of dignity also remain in contemporary world. Care and politeness have always been understood as essential means of cultivating dignity in interpersonal relationships, but they can differ from culture to culture. While autonomy is highlighted as the philosophical foundation of human rights, balancing an individual’s autonomy with the other meanings of dignity is central to discussions of many social issues.

The plurality of dignity enables positive discussions that contribute to the development of service design and expansion of its boundaries. I propose a list of research questions and an overarching research agenda that provide opportunities to enrich existing work on the importance of service in societies. Table 1 presents applied questions that arise from each perspective of dignity, and Table 2 is a collection of theoretical questions that can be asked regardless of the perspective, so as to guide future research that investigates dignity in service design.

Table 1. Research questions based on different conceptions of dignity.

| Merit |

|

| Autonomy |

|

| Universal rights |

|

| Interpersonal care |

|

Table 2. Research agenda to utilize the pluralistic framework of dignity in service design.

| What |

|

| Who |

|

| How |

|

| When Where |

|

| Why |

|

What: There is a need to enrich the study of dignity with area-specific definitions and terminologies from applied perspectives. As a foundational moral principle, dignity promotes the interdisciplinary collaborations, where in-depth discussions about dignity are essential to cultivate human-centered approaches. The pluralistic framework of dignity will support the development of applied knowledge generated by research inquiries that address the complex social problems manifested through services. Expanding the meaning of dignity by making connections to a particular field will be especially relevant when applying the dignity framework to a service design project in that field. For example, a legal design project will need to explore the concept of dignity from a legal ethical perspective to make a connection to the ethnographic research that reveals the factors and patterns determining how people experience dignity or indignity in the context of a legal system.

Who: The framework of dignity can be used to model the different perspectives of stakeholders to prevent service failure and promote a flexible recovery process. Additionally, consideration of dignity expands the boundary of stakeholders to include laborers, managers, and communities in which the service is positioned. There is a need to incorporate socioeconomic research in the study of dignity to better understand service labors. For example, McDowell (2011) discussed how emotional and embodied attributes have become an essential part of service co-production and how the graded sets of attributes create gendered and racialized suitability hierarchies of work and wage differences. Further, if we expand the meaning of dignity to the value of life, the boundary of stakeholders could be expanded to include other living beings and the environment.

How: The pluralistic conceptualizations of dignity can lead to diverse service concepts. The framework can also inspire the development of design methods, such as research tools and design models, that emphasize the experience of dignity on multiple levels. For example, attention to dignity will promote the use of participatory methods and processes that respect the dignity of the stakeholders from various perspectives. Particularly, there is a demand for designing a system to re-examine a service after a controversial incident. For example, in 2018, in response to public outcry about two black men being arrested for sitting in a Starbucks, the company officially apologized and closed all of its stores for one day to conduct workshops on racial bias (Siegel & Horton, 2018).

When and where: In relation to methods and tools, it is important to discuss when the framework of dignity should be used and where it is particularly salient, like different sectors of services or phases of a design process. As service is co-produced by the stakeholders, which is a separate process from design, there is a need to develop participatory systems and guidance to ensure that dignity permeates the service encounters. In addition to systematizing sensitivity and the consideration of dignity in design practice and the service industry, these factors must be embedded in design education and critiques. Dignity also plays a critical role in discussing the future of service should humans be replaced or supported by technology, such as robots and virtual reality.

Why: Implementing dignity in methodology is not enough because methods can be altered when situations change. Therefore, the principle of dignity must be discussed and thoroughly studied so that the why supports the how. A theoretical examination of dignity must accompany the development of methods and tools to allow for its exploration as a principle of service design. This will help us to develop knowledge that fosters service organizations and service communities with the fundamental goal of improving the world and enhancing people’s lives.

Scholars propose embedding perspectives from design ethics in a design process for systematical application in practice (Carlsson, 2013; Friedman, 1996; Fry, 2009). I present ideas for tools and methods so that designers can consider dignity in the process of service design and co-production (Table 3). Service design often starts with evaluating an existing service and understanding the subject area of the particular project. Dignity evaluation tools, such as design metrics or assessment questions, can be helpful in this phase. Additionally, the dignity framework can be used as a canvas for organizing area-specific terms that help situate dignity in the context of the particular project. These tools will help an interdisciplinary team to better map their service territory, form a shared understanding of key values, and identify the opportunities that exist in the problem area.

Table 3. Potential tools to nurture service design process with dignity.

| Definition |

|

| Research |

|

| Ideation |

|

| Development |

|

| Co-production |

|

In the following phase, designers typically conduct ethnographic research, such as interviews and observations, or participatory research with the key stakeholders of the service. In this phase, it is essential to set up a clear protocol to protect the dignity of the participants in the research and analysis. Additionally, a standard and validated questionnaire to generate interview questions or surveys on dignity will be useful. The models that represent research outcomes, such as a stakeholder map or a customer journey map, can also utilize the dignity framework.

In the ideation phase, creating a holistic service concept serves as the identity that gives consistency to the service. The dignity framework can help designers to examine the similar services in the market to understand what kinds of dignity principles operate behind them and identify opportunities for creating a distinctive service strategy. A service concept based on a clear principle will enhance communication with the stakeholders of the service, help manage their expectations, and enhance the quality of experience within the service encounter. The dignity framework can also inspire designers to develop new tools for brainstorming and idea generation, such as a set of cards with questions that prompt users to think critically about dignity.

When developing specific moment concepts and product/interface ideas along the touchpoints, an archive that captures potential service controversies, failures, and suggested recovery solutions can be helpful. For example, an online platform where designers can collect cases in which conflicts have arisen, explain how those cases escalated into incidents of service indignity, and explicate how they were resolved would be a useful reference. Additionally, an interactive tool that can help designers to prototype service experiences and then test them based on diverse stakeholders’ perspectives and concepts of dignity can be a useful resource for designers to iterate the product-service system to prevent service failures. Designers can also add a layer examining the service from the perspective of dignity to design tools such as a service blueprint.

Even after delivering the solution to the community of use, designers can provide tools to continuously support the stakeholders to manage the service. For example, workshops and toolkits can help them to evaluate the service from the perspective of dignity, discuss and update the manuals and processes accordingly, train the new members, and nurture an organizational culture that promotes dignity. It would be ideal to prevent service indignity incidents, but more important is a flexible response to a problem and the provision of an immediate recovery. To do this, the organization should provide training, protocols, and policies designed to empower the service workers to make decisions and properly communicate to resolve issues based on the dignity principles. A procedure and platform needs to be designed so that stakeholders can have access to those who will hear their concerns and advocate for them if necessary.

Conclusion

This paper examined four concepts of dignity. If we view humans as functional elements of a system, dignity can be seen as a merit that reflects an individual’s contributions to a system. Dignity is a form of autonomy expressed when we nurture the individual’s capability of choice and free action. Furthermore, dignity comprises universal rights if we focus on the development of equitable and inclusive systems to support society. If we highlight the emotional needs of individuals, dignity can be found in respectful interpersonal care.

By proposing the dignity framework and research questions, this paper aims to provide a common ground and shared language so that designers can discuss the concept of dignity in an explicit manner, examine related assumptions behind services, and deliberate about them with colleagues, non-designer collaborators, and stakeholders. For example, a 3D-printed capsule that carries out euthanasia has just been legalized in Switzerland in December 2021 (Keith, 2021); discussions about such controversial service can benefit from a framework that account for multiple perspectives. Furthermore, we need a framework to better understand how different conceptions of dignity shape services. In fact, these multiple perspectives already co-exist in today’s societies, even in one service. For example, business and economy classes on a flight are differentiated by a capitalistic merit system, while the invitation to preboard is a civil right guaranteed to disabled passengers. The framework of dignity can also nurture sensitivity for cultural specificities and regional contexts. For example, some airlines have designed services to assist individuals’ religious needs, such as dedicated prayer rooms with an indicator toward Mecca and meal services that align with the time to break the fast during Ramadan. As Carlsson (2013) proposes, service design is an area where designers work with local and global norms and multiple values, which stresses the importance of the framework upon which diversified ethical considerations are made.

Services in the future will also require pluralistic approaches to examine how the conventions of existing services and their appreciations of dignity are translated into artificial intelligence. For example, what should the algorithm be for a shared self-driving car service? Should it consider the human rights needs of neighborhoods and societal groups, the urgency and care needs of the individuals, the balance with passenger’s autonomy, or a merit system determined by carbon footprint instead of money? Designers need systematic ways to analyze existing services that are already operating with pluralistic conceptions of dignity to be able to articulate the fundamental origins of problems and promote solutions that support the perspectives that befit the new needs of ever-changing societies. The framework of dignity can elicit productive discussions that supplement the utilitarian principles of making by exploring design theories and ethics, supporting the meaning-making and value co-creation of the stakeholders, and developing methods and tools for design practice in the future.

References

- Alkire, L., Mooney, C., Gur, F. A., Kabadayi, S., Renko, M., & Vink, J. (2019). Transformative service research, service design, and social entrepreneurship: An interdisciplinary framework advancing wellbeing and social impact. Journal of Service Management, 31(1), 24-50. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-05-2019-0139

- Allan, D. J. (1953). Aristotle’s account of the origin of moral principles. Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Philosophy, 12, 120-127. https://doi.org/10.5840/wcp11195312392

- Anderson, L., Ostrom, A. L., Corus, C., Fisk, R. P., Gallan, A. S., Giraldo, M., & Shirahada, K. (2013). Transformative service research: An agenda for the future. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1203-1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.013

- Anglesey, A. (2021, April 6). Burger King worker strangled by customer following mask dispute, police say. Newsweek. Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/burger-king-worker-strangled-customer-following-mask-dispute-police-say-1581191

- Aristotle (n.d./1998). Aristotle: The metaphysics (H. Lawson-Tancred, Trans.). London, England: Penguin Books.

- Barbic, S. P., Chan, N., Rangi, A., Bradley, J., Pattison, R., Brockmeyer, K., & Leon, A. (2019). Health provider and service-user experiences of sensory modulation rooms in an acute inpatient psychiatry setting. PLoS One, 14(11), e0225238. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225238

- Bendix, A. (2017, May). United Airlines testifies before an angry congress. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/news/archive/2017/05/united-airlines-testifies-before-congress/525192

- Buchanan, R. (2001). Human dignity and human rights: Thoughts on the principles of human-centered design. Design Issues, 17(3), 35-39. https://doi.org/10.1162/074793601750357178

- Buchanan, R. (2019). Systems thinking and design thinking: The search for principles in the world we are making. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 5(2), 85-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2019.04.001

- Carlsson, B. (2013). The ethical ecology of service design-An explorative study on ethics in user research for service design. In Proceedings of the Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation (Article no. 67, pp. 71-76). Espoo, Finland: Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Chase, R. B., & Dasu, S. (2001). Want to perfect your company’s service? Use behavioral science. Harvard Business Review, 79(6), 78-85.

- Clarke, I. (2009). Design and dignity in hospitals. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, 98(392), 419-428. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25660704

- Clarkson, P. J., Coleman, R., Keates, S., & Lebbon, C. (2013). Inclusive design: Design for the whole population. Berlin, Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-0001-0

- Constituteproject.org. (1949/2014). Germany’s constitution of 1949 with amendments through 2014. Retrieved from https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/German_Federal_Republic_2014.pdf?lang=en

- Cook, L. S., Bowen, D. E., Chase, R. B., Dasu, S., Stewart, D. M., & Tansik, D. A. (2002). Human issues in service design. Journal of Operations Management, 20(2), 159-174. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(01)00094-8

- Darwell, S. (2017). Equal dignity and rights. In R. Debes (Ed.), Dignity: A history (pp. 181-202). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199385997.003.0009

- Debes, R. (2017). Human dignity before Kant. Denis Diderot’s passionate person. In R. Debes (Ed.), Dignity: A history (pp. 203-236). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199385997.003.0010

- De Wit, B., & Meyer, R. (2009). Strategy: Process, content, context: an international perspective. Lodon, England: Thomson Learning.

- Dewey, J. (1891). Moral theory and practice. The International Journal of Ethics, 1(2), 186-203. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2375407

- Dorst, K., & Dijkhuis, J. (1995). Comparing paradigms for describing design activity. Design Studies, 16(2), 261-274. https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-694X(94)00012-3

- Fisk, R. P., Dean, A. M., Alkire, L., Joubert, A., Previte, J., Robertson, N., & Rosenbaum, M. S. (2018). Design for service inclusion: Creating inclusive service systems by 2050. Journal of Service Management, 11(2), 77-83. http://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-05-2018-0121

- Foley, S. M. (2018). Service design for delivery of user centered products and services in healthcare. Journal of Commercial Biotechnology, 24(1), 69-77. https://doi.org/10.5912/jcb855

- Forty, A. (1995). Objects of desire: Design and society since 1750. London, England: Thames and Hudson.

- Friedman, B. (1996). Value-sensitive design. Interactions, 3(6), 16-23. https://doi.org/10.1145/242485.242493

- Fry, T., (2009). Design futuring: Sustainability, ethics and new practice. Sydney, Australia: UNSW Press.

- Fuller, R. W., & Gerloff, P. (2008). Dignity for all: How to create a world without rankism. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Gemes, K., May, S., & May, S. P. W. (2009). Nietzsche on freedom and autonomy. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Gewirth, A. (1984). Rights and virtues. Analyse & Kritik, 6(1), 28-48. https://doi.org/10.1515/auk-1984-0103

- Gibson, K. (2021, May 30). Flight attendant’s bloody assault by passenger part of disturbing trend. CBS News. Retrieved from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/flight-attendant-assault-passenger-southwest

- Goldbaum, C. (2020, September 18). When a bus driver told a rider to wear a mask, ‘He knocked me out cold’. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/18/nyregion/mta-bus-mask-covid.html

- Goldstein, S. M., Johnston, R., Duffy, J., & Rao, J. (2002). The service concept: The missing link in service design research? Journal of Operations Management, 20(2), 121-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(01)00090-0

- Gordis, W. S. (1905). The estimates of moral values expressed in Cicero’s letters. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Griffin, J. (2008). On human rights. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Griffin, M. (2017). Dignity in roman and stoic thought. In R. Debes (Ed.), Dignity: A history (pp. 47-66). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199385997.003.0003

- Grinberg, E., & Yan, H. (2017, April 12). United fallout: Airline offers compensation, passengers say. CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2017/04/12/travel/united-passenger-pulled-off-flight

- Hare, R. M. (1991). The language of morals (No. 77). Oxford, England: Oxford Paperbacks. http://doi.org/10.1093/0198810776.001.0001

- Heskett, J. (1980). Industrial design. London, England: Thames and Hudson.

- Hicks, D. (2011). Dignity: The essential role it plays in resolving conflict. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Hobbes, T. (1651/1904). Leviathan: Or, the matter, forme and power of commonwealth, ecclesiasticall and civill. Cambridge, England: University Press.

- Holmlid, S., & Evenson, S. (2008). Bringing service design to service sciences, management and engineering. In B. Hefley & W. Murphy (Eds.), Service science, management and engineering education for the 21st century (pp. 341-345). Boston, MA: Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-76578-5_50

- Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hosking, I., Cornish, K., Bradley, M., & Clarkson, P. J. (2015). Empathic engineering: Helping deliver dignity through design. Journal of Medical Engineering & Technology, 39(7), 388-394. http://doi.org/10.3109/03091902.2015.1088090

- Irwin, T. (2015). Transition design: A proposal for a new area of design practice, study, and research. Design and Culture, 7(2), 229-246. http://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2015.1051829

- Jafarinaimi, N. (2011). An Inquiry into the form of social Interaction in contemporary products (Doctoral dissertation). Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA.

- Junginger, S., & Sangiorgi, D. (2009). Service design and organisational change. Bridging the gap between rigour and relevance. In Proceedings of the Conference of International Association of Societies of Design Research (pp. 4339-4348). Seoul, Korea: IASDR.

- Kabadayi, S., Alkire, L., Broad, G. M., Livne-Tarandach, R., Wasieleski, D., & Puente, A. M. (2019). Humanistic management of social innovation in service (SIS): An interdisciplinary framework. Humanistic Management Journal, 4(2), 159-185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41463-019-00063-9

- Kant, I. (1785/1998). Groundwork for the metaphysics of morals (M. Gregor, Trans.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Karpen, I. O., Gemser, G., & Calabretta, G. (2017). A multilevel consideration of service design conditions. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(2), 384-407. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-05-2015-0121

- Karwan, K. R., & Markland, R. E. (2006). Integrating service design principles and information technology to improve delivery and productivity in public sector operations: The case of the South Carolina DMV. Journal of Operations Management, 24(4), 347-362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2005.06.003

- Keith, M. (2021, Dec 5). 3D-printed suicide pods are now legal in Switzerland. Business Insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/sarco-machines-3d-printed-capsule-assisted-suicide-pod-booth-switzerland-2021-12

- Kelleher, C., & McGilloway, S. (2005). Survey finds high levels of work-related stress among flight attendants. Cabin Crew Safety, 40(6), 1-5.

- Kent, B. (2017). In the image of God. In R. Debes (Ed.), Dignity: A history (pp. 73-98). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199385997.003.0005

- Kim, H. (2015). Person, place, hospitality. Seoul, Korea: Literature and Intelligence Press.

- Kim, S. (2021, January 19). ‘Violent’ customer attacks grocery store worker with bottle after being asked to wear mask. Newsweek. Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/coronavirus-washington-state-mask-mandate-grocery-store-employee-attacked-1562512

- Kim, M. (2018a). An inquiry into the nature of service: A historical overview (part 1). Design Issues, 34(2), 31-47. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00484

- Kim, M. (2018b). Designing for participation: Dignity and autonomy of service (Part 2). Design Issues, 34(3), 89-102. https://doi.org/10.1162/desi_a_00499

- Kimbell, L. (2011). Designing for service as one way of designing services. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 41-52.

- Korper, A. K., Holmlid, S., & Patrício, L. (2021). The role of meaning in service innovation: A conceptual exploration. Journal of Service Theory and Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-01-2020-0004

- Kottasova, I. (2017). United loses $250 million of its market value. CNN. Retrieved from https://money.cnn.com/2017/04/11/investing/united-airlines-stock-passenger-flight-video/

- Krippendorff, K. (2008). The diversity of meanings of everyday artifacts and human-centered design. In L. Feijs, M. Hessler, S. Kyffin, & B. Young (Eds.), Design and semantics of form and movement (pp. 12-19). Offenbach am Main, Germany: Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V.

- Lapinski, J. (2008, March 26). Cultural differences in marketing. Retrieved from https://jenslapinski.com/2008/03/26/cultural-differences-in-marketing/

- LaVaque-Manty, M. (2017). Universalizing dignity in the nineteenth century. In R. Debes (Ed.), Dignity: A history (pp. 301-322). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199385997.003.0015

- Lazo, L. (2017, March 26). Two girls barred from United flight for wearing leggings, The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/dr-gridlock/wp/2017/03/26/two-girls-barred-from-united-flight-for-wearing-leggings

- Lebovich, W. L. (1993). Design for dignity: Studies in accessibility. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Le Dantec, C. A., & Edwards, W. K. (2008). Designs on dignity: Perceptions of technology among the homeless. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 627-636). New York, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1357054.1357155

- Lefebvre, R. C. (2012). Transformative social marketing: Co-creating the social marketing discipline and brand. Journal of Social Marketing, 2(2), 130-137. https://doi.org/10.1108/20426761211243955

- Levitt, T. (1972). Production-line approach to service. Harvard Business Review, 50(5), 41-52.

- Manzini, E. (2011). Introduction to design for services. In A. Meroni & D. Sangiorgi (Eds.), Design for services (pp. 1-8). Aldershot, England: Gower Publishing.

- Margalit, A. (1998). The decent society. Cambridge, England: Harvard University Press.

- Macklin, R. (2003). Dignity is a useless concept: It means nothing more than respect for persons or their autonomy. British Medical Journal, 327(7429), 1419-1420. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7429.1419

- McCurry, J. (2016). Singer Richard Marx ‘helps restrain man’ on flight and criticises crew. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/21/singer-richard-marx-restrain-man-flight-crew-korean-air

- McCrudden, C. (2008). Human dignity and judicial interpretation of human rights. European Journal of International Law, 19(4), 655-724. http://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chn043

- McDowell, L. (2011). Working bodies: Interactive service employment and workplace identities. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- McKeon, R. (1990). Philosophy and history in the development of human rights. In Z. K. McKeon (Ed.), Freedom and history and other essays: An introduction to the thought of Richard McKeon. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- McNeil, R., & Guirguis-Younger, M. (2014). Dignity in design: The siting and design of community and shelter-based health facilities for homeless persons. In M. Guirguis-Younger, R. McNeil, & S. Hwang (Eds.), Homelessness & health in Canada (pp. 233-255). Ottawa, Canada: University of Ottawa Press.

- Meroni, A., & Sangiorgi, D. (2011). Design for services. Aldershot, England: Gower Publishing.

- Miettinen, S., & Koivisto, M. (2009). Designing services with innovative methods. Helsinki, Finland: University of Art and Design Helsinki.

- MinNews (n.d.). Japan Airlines first-class cabin exposure, flight attendants help warm the bed, kneeling service “greet” VIP passengers. MinNews. Retrieved from https://min.news/en/aviation/c1471c12258e36a161e1588225e960cb.html

- Norman, D. (2013). The design of everyday things (Rev. and exp. ed.). New York, NY: Basic books.

- Parse, R. R. (2010). Human dignity: A human becoming ethical phenomenon. Nursing Science Quarterly, 23(3), 257-262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318410371841

- Patrício, L., Fisk, R. P., Falcão e Cunha, J., & Constantine, L. (2011). Multilevel service design: From customer value constellation to service experience blueprinting. Journal of Service Research, 14(2), 180-200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511401901

- Pevsner, N. (1936). Pioneers of the modern movement from William Morris to Walter Gropius. London, England: Faber & Faber.

- Pico Della Mirandola, G. (1486/1996). Oration on the dignity of man (A. R. Gaponigri, Trans.). Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing.

- Porterfield, C. (2020, August 15). No-mask attacks: Nationwide, employees face violence for enforcing mask mandates. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/carlieporterfield/2020/08/15/no-mask-attacks-nationwide-employees-face-violence-for-enforcing-mask-mandates/?sh=6ef98bc660d6

- Rams, D. (2009). Ten principles of good design. In K. Ueki-Polet & K. Klemp (Eds.), Less and more: The design ethos of Dieter Rams. Berlin, Germany: Gestalten.

- Rao, N. (2011). Three concepts of dignity in constitutional law. Notre Dame Law Review, 86(1), Article 4. https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol86/iss1/4

- Rosen, M. (2012). Dignity: Its history and meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Rowden, E., & Jones, D. (2018). Design, dignity and due process: The construction of the Coffs Harbour Courthouse. Law, Culture and the Humanities, 14(2), 317-336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1743872115612954

- Sangiorgi, D., & Clark, B. (2004). Toward a participatory design approach to service design. In Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Participatory Design (pp. 148-151). New York, NY: ACM.

- Sarre, J. (2007). Dignity through design-how the architecture can make a difference. Working With Older People, 11(2), 28-31. https://doi.org/10.1108/13663666200700028

- Seshadri, P., Joslyn, C. H., Hynes, M., & Reid, T. (2019). Compassionate design: Considerations that impact the users’ dignity, empowerment and sense of security. Design Science, 5, e21. https://doi.org/10.1017/dsj.2019.18

- Shell, S. M. (2008). Kant’s concept of human dignity as a resource for bioethics. In A. Schulman (Ed.), Human dignity and bioethics: Essays commissioned by the president’s council on bioethics (pp. 333-349). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Siegel, R., & Horton, A. (2018). Starbucks to close 8,000 stores for racial-bias education on May 29 after arrest of two black men. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2018/04/17/starbucks-to-close-8000-stores-for-racial-bias-education-on-may-29-after-arrest-of-two-black-men/

- Spiegelberg, H. (1971). Human dignity: A challenge to contemporary philosophy. The Philosophy Forumo, 9(1-2), 39-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.1971.9971711

- Steinbuch, Y. (2017, April 24). American Airlines passenger explains why he defended mom hit with stroller. New York Post. Retrieved from https://nypost.com/2017/04/24/american-airlines-passenger-explains-why-he-defended-mom-hit-with-stroller

- Stickdorn, M., & Schneider, J. (2011). This is service design thinking: Basics, tools, cases. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Sudbury-Riley, L., Hunter-Jones, P., Al-Abdin, A., Lewin, D., & Naraine, M. V. (2020). The trajectory touchpoint technique: A deep dive methodology for service innovation. Journal of Service Research, 23(2), 229-251. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670519894642

- Sullivan, L. H. (1896). The tall office building artistically considered. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott.

- United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/udhr.pdf

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2008). Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0069-6

- Waldron, J., & Dan-Cohen, M. (2012). Dignity, rank, and rights. Oxford, England: Oxford University. http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199915439.001.0001

- Wetter-Edman, K. (2014). Design for service: A framework for articulating designers’ contribution as interpreter of users’ experience (Doctoral dissertation). University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden.

- White, C. (2017, April 14). Doctor dragged from United Airlines flight claims it was worse than Vietnam war. Metro. Retrieved from https://metro.co.uk/2017/04/14/doctor-dragged-from-united-airlines-flight-claims-it-was-worse-than-vietnam-war-6574555/?ito=cbshare

- Williams, D. S. (2008). Design with dignity: The design and manufacturing of appropriate furniture for the bariatric patient population. Bariatric Nursing and Surgical Patient Care, 3(1), 39-40. https://doi.org/10.1089/bar.2008.9993

- Wray, M. (2020, February 01). ‘I just shut up and bear it’: What it’s like to travel while larger-bodied. Global News. Retrieved from https://globalnews.ca/news/6373156/travelling-while-fat

- Ylirisku, S., & Arvola, M. (2018). The varieties of good design. In P. E. Vermaas & S. Vial (Eds.), Advancements in the philosophy of design (pp. 51-70). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.