Narrating Service Design to Account for Cultural Plurality

Zhipeng Duan *, Josina Vink, and Simon Clatworthy

The Oslo School of Architecture and Design, Oslo, Norway

Stories create pathways from the past to the future. How are the stories of service design practice being told? What futures are they creating? Many service design narratives in public and academic discourse are dominated by concepts that refer to “mainstream” service design knowledge. Those who diverge from this mainstream—including service design practitioners and participants involved in culturally situated practices—risk being assimilated by service design concepts that take a monolithic view of culture. Moreover, this dominant service design narrative threatens to extend coloniality. In response, we introduce cultural plurality as a way to highlight the ontological conditions in which different practices enact different realities and futures beyond the scope of service design. To investigate and reflect on how service design practice is narrated within multiple cultures, we present four representative stories of service design practice, derived from a literature review and interviews with 21 service design practitioners with diverse, global backgrounds. The main contribution of the study is its demonstration that the dominant narrative is insufficient to tell the story of service design across multiple cultures. On the basis of this reflexive study, we encourage service design knowers to practice narrative sensitivity, in order to allow room for entangled, multidirectional practices. We further stress the importance of cultivating vigilance regarding the presence of mainstream service design knowledge and concepts, amid a meshwork of differing knowledges and practices.

Keywords – Narrative, Culture, Plurality, Service Design Knowledge.

Relevance to Design Practice – This article helps service design practitioners to critically reflect on the knowledge and concepts they use when telling the stories of their practices and those of their participants in the service design process. It encourages practitioners to bravely and carefully tell stories that reconnect designing with other world-making practices that decentralize and disrupt the dominant service design narrative.

Citation: Duan, Z., Vink, J., & Clatworthy, S. (2021). Narrating service design to account for cultural plurality. International Journal of Design, 15(3), 11-28.

Received Oct. 26, 2020; Accepted Oct. 30, 2021; Published Dec. 31, 2021.

Copyright: © 2021 Duan, Vink, & Clatworthy. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: duan.zhipeng@aho.no

Zhipeng Duan is a PhD candidate in Service Design at The Oslo School of Architecture and Design. His research explores the praxis of design, especially service design, in an evolving cultural context. His work aims to build a better understanding of service design, to support design practitioners cultivating cultural sensitivity, and to further the imaginations of the boundaries of design in the plurality. As part of the Centre for Connected Care (C3), his PhD is particularly entangled with the transformation of healthcare services in both Norway and China.

Josina Vink is Associate Professor of Service Design at The Oslo School of Architecture and Design and Design Lead within the Centre for Connected Care (C3). Josina’s research focuses on building a systemic understanding of service design and developing approaches for shaping social structures through design. They have published in journals such as Design Studies, the Design Journal, Journal of Service Management, and Journal of Service Research. Josina has over a decade of experience working as a service designer in health and care in North America and Scandinavia. They have extensive experience leading and facilitating participatory system and service design processes in health care, government, non-profit, and community settings. In their practice, Josina has developed new services, supported policy change, facilitated shifts in practices across sectors, and led social lab processes.

Simon Clatworthy is professor at The Oslo School of Architecture and Design. He has grappled with important questions in Service Design since 2003, and has published several books and articles within the Service Design field.

Introduction

In the research phase of her project, Anna, an Italian service designer, conducted observations, questionnaires, and interviews with different stakeholders to understand the status quo of ecotourism in China. She joined a guide and tourists to take a tour to Yunnan. She shadowed them throughout the trip to observe how they communicated and learn about their behaviors and needs. Through these different approaches, she gleaned a wealth of findings on ecotourism. She condensed these findings into five key insights about specific needs and problems, which she used to produce a solution for ecotourism in China that consists of a physical toolkit of cards, maps, and booklets for tourists. With this toolkit, she hoped to facilitate tourists’ decisions about sustainable tourism when planning their Chinese itineraries.

We recount this story that comes from an interview with a service design practitioner. We narrate Anna’s practice by employing a variety of service design concepts, including observations, questionnaires, interviews, findings, needs, problems, and solutions. According to these concepts, Anna’s story seems logical and in line with “mainstream” service design knowledge. In this article, we aim to problematize the coherence of this story. We emphasize the need for reflexivity among service design knowers, including researchers and practitioners, when constructing narratives about service design within and across multiple cultures. For this study, the term narrative refers to a knowledge-making practice through which the knower accounts for practices that represent a connected succession of occurrences. Differing narratives open up different worlds (Goodman, 1978); as Ingold (2007, p. 93) suggests, “to tell a story is to relate, in narrative, the occurrences of the past retracing a path through the world that others, recursively picking up the threads of past lives, can follow in the process of spinning out their own.” Along the paths of stories, those who are reading or listening envision future scenarios and weave those scenarios into their lives (Ingold, 2007). Thus, the narratives of service design practice constitute a world-making project based on service design knowledge.

In the past two decades, increasing discussion centers on the relationship between service design and culture, including the performance of service design in different cultural contexts (e.g., Taoka et al., 2018) and the influence of service design on cultures (e.g., Sangiorgi, 2011). Within this discourse, a dominant narrative tells the story of practice through concepts related to service design knowledge. This dominant narrative produces a rather monolithic view of culture that ignores the heterogeneity of people and presents their practices as a relatively even and homogenous collective; it names and objectifies the features of that collective through a common set of service design concepts. As a result, differing stories about making the future get told in only one language, which threatens to extend coloniality.

To reflect on the dominant narrative, we deliberately integrate service design with discussions from anthropology and from science, technology, and society (STS), two disciplines that have committed to wrestling with the situated complexity and relationality of diverse practices and sites (Otto & Bubandt, 2010). Within these entangled disciplines, scholars propose the pluriverse as a central concept for helping ethnographers recognize the radical coexistence of multiple forms of practice, life, and future—rather than assimilating them through one set of knowledge (Stengers, 2018). A key claim is that different practices enact different realities and futures amid collectives (Law, 2015). These discussions are illuminating, because they disrupt the dominant narrative by acknowledging that various practices in various cultures are capable of world-making beyond the scope of service design. By drawing from these discussions of the pluriverse, we use cultural plurality to highlight the ontological condition of the coexistence of divergent cultural practices, as well as explore how service design knowers can narrate service design practices in ways that better account for cultural plurality.

Based on a literature review and interviews with 21 service design practitioners, we investigated and reflected on how we as service design knowers narrate practices. Informed by literature on service design in relation to culture, we articulated the dominant narrative through four patterns: service design describing, adapting to, shaping, and enacting cultures. To investigate these patterns, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 21 service design practitioners and then coded the interviews to perform narrative analysis. Many stories mirror the patterns of the dominant service design narrative; we selected one story that best represents each pattern to further analyze. By revisiting the interviews to bring more contextual information into their scope, we then examined the stories to interrogate how cultural plurality is being erased and how a more decentralized narrative of service design can be restored.

The main contribution of our study is its demonstration that the monolithic cultural view of the dominant narrative is insufficient for telling the stories of service design that arise from the landscapes of multiple cultures. We reveal a crisis in the service design narrative, caused by its inability to interpret practices of making futures other than by translating them into the knowledge of service design. As an emergent discipline, service design has potentials and flexibility to confront this crisis in order to relate to other world-making projects in a more respectful way. Our secondary contribution is that we invite service design knowers to decentralize service design narratives, by allowing room for heterogeneity and acknowledging the diversity and entanglement of practices. To promote such decentralization, we propose a narrative sensitivity that alerts practitioners to the presence of service design concepts and the encroachment of mainstream knowledge in the telling of future-making stories.

Dominant Narrative of Service Design

Service design literature features a dominant service design narrative that supports the proliferation of mainstream service design knowledge. Within this narrative, knowers rely almost exclusively on communicating through common concepts that are elaborated by mainstream service design and other modern knowledge. These concepts can portray people (e.g., designers, users, customers, stakeholders) and design activities (e.g., workshops, prototypes, methods, tools). They produce recursive knowledge by constantly explaining and assimilating various practices and becoming a repertoire shared by knowers (Blaser & De la Cadena, 2018). For example, claiming the use of similar service design tools is a mark of service designers (Fayard et al., 2017). When a practice is narrated, knowledge can be recognized by its work of displacement, in that it claims what the practice is, rather than its concepts (Verran, 2018). For service design knowers, the dominant narrative, brought forward through existing concepts, makes the practice of service design recognizable by the service design community [see anthropologist Strathern’s (2018) reflective work on the divergence of knowledge practices].

When we apply these concepts, we tend to assume the collective features are perfectly and homogeneously shared among people and their practices. As such, the features can be named, compared, and functionalized by the usage of a set of concepts. In doing so, we assert that dominant service design concepts reproduce a monolithic view of culture. We anchor our understanding of culture on the condensed definition from Eriksen (2001, p. 3) that culture is “abilities, notions and forms of behavior people have acquired as members of society.” According to this understanding, the identification of a group of people is a typical cultural practice that exploits difference to form different social groups (Appadurai, 1996). Delineation of a user group often implies that the service design knower believes users have similar behavioral patterns or needs (Matthews et al., 2012). Service design concepts are linked to broader existing cultural concepts, such as Asian or African service design methods. Within this monolithic view of culture, the cultural concepts tend to be misunderstood and misapplied, as differences encountered in practices are labeled as reflecting a culture to designate a feature that is evenly-shared among the social group, without careful examination (Brumann, 1999). This view shadows the value of culture that refers to materials, collective emotions, and practices that arise inherently in people’s daily interactions and are inherently connected to the knowledge, wisdom, histories, and philosophies of localities. Anthropologists Breidenbach and Nyíri (2011) argue that design’s practices of ethnography present a container view of culture through which cultural concepts are being instrumentalized by applying them to whatever values and needs design wishes to meet. Furthermore, the concept of culture itself often becomes the direct object of service design in the narrative.

This dominant service design narrative reinforces a monolithic view of culture that is exemplified by prominent narratives of service design in relation to organizational cultures. In service design literature, definitions of organizational cultures often are informed by organizational studies in social science. For example, Aguirre (2020) uses Ruigrok and Achtenhagen’s (1999) definition of organizational culture as the norms, beliefs, meanings, and behaviors shared by all organizational members or specific sub-groups (e.g., employees) that can be conveyed to new members. Service design discourse tends to build an overall understanding of actions and features of an organization through service design tools (e.g., Holmlid & Evenson, 2008; Kurtmollaiev et al., 2018; Stuart, 1998). The behavioral patterns, values, and meanings of organizational members, implied by the concept of organizational culture, are changeable objects in narrating the purpose of service design practice (e.g., Sangiorgi, 2011). Furthermore, scholars suggest that service design needs to adapt to different organizational cultures (Junginger, 2015); Rauth et al. (2014) stress the importance of adjusting service design approaches to ensure their fit and acceptance by various organizational cultures. Practicing service design within organizations also entails self-proliferation, in that a key goal of service design is to spread a service design culture (e.g., human-centered design culture, participatory culture), such as by building an organization’s design capabilities (e.g., Mahamuni et al, 2020; Malmberg, 2017; Seidelin et al., 2020).

Our concern about this dominant narrative in service design is not its effectiveness in relation to the practice but its coloniality. The narrative potentially delocalizes and disembodies service design knowledge by oversimplifying heterogeneous practices of service design (Tlostanova, 2017). Narration of practice extensively through these shared concepts relates closely to the tradition of abstraction in Western rationalism (Escobar, 2018). Coloniality requires a translation that assimilates different practices into one set of abstract narratives. This translation happens when similarities and differences between people and their practices are sought through the lens of knowledge (Blaser & De la Cadena, 2018; Ingold, 2018). Defining such similarities and differences is not a neutral act though; it is based on a particular worldview. Tsing (2015) suggests that such translation requires banishing incommensurable differences encountered in practices, to smoothly organize and narrate practices such as service design (e.g., the global popularity of the Double Diamond; Akama et al., 2019), along with its existing logics. Through translation, this abstract narrative occupies a universal and neutral vantage point to tell a future-making story while eliminating other ways to narrate the transformation rooted in other worldviews (Tlostanova, 2017). The design practices of different people are framed as a global, homogenous service design question that seeks a “Western” answer (Akama & Yee, 2016).

Narrating Service Design for Cultural Plurality

Because of these considerations, there is an urgent need to deviate from the dominant service design narrative to appreciate concealed heterogeneities of practices that are often lost in translation. Informed by studies of the pluriverse in anthropology (e.g., Blaser & De la Cadena, 2018; Verran, 2018), STS studies (e.g., Law, 2015), and design (e.g., Escobar, 2018), we propose the concept of cultural plurality to highlight the ontological condition that multiple human beings, their practices, and enacted realities coexist within collectives. According to this convergence of studies on the pluriverse and service design, we deliberately elaborate on how cultural plurality can encourage deviation from the dominant service design narrative.

There is a widespread belief in a universal world in design disciplines (Escobar, 2018), whereby all human beings live in a single world, made up of one nature, with many cultures generated from the nature (Ingold, 2018; Law & Lien, 2018). In this way, different cultures refer to multiple perspectives on one reality. This wide belief forms the basis of neoliberal globalization (Escobar, 2018). Because the dominant knowledge of service and design aligns firmly with the tradition of rationalism and neoliberalism (e.g., Escobar, 2018; Kim, 2018), this belief in a universal world also is rooted in service design narratives. This worldview tends to encourage service design practitioners to employ replicable methods, scalable solutions, and shared service concepts to address a “common” problem for a group of people, because they are in one reality (Akama et al., 2019). Cultural plurality challenges this idea of a common reality; it calls for attention to the ontological condition that different practices enact different realities and therefore make different worlds (Law, 2015). To acknowledge multiple realities is to perceive that the making of worlds is not the exclusive provenance of professional design, but is a meshwork of practices in which service design is one or several threads of world-making that are knotted together with other different world-making paths (Ingold, 2007; Suchman, 2011).

Acknowledgment of cultural plurality demands that knowers cultivate self-vigilance regarding the presence of their service design knowledge, especially the knowledge they take for granted (Tlostanova, 2017). In this way, designing within cultural plurality requires a humbleness that one’s knowledge is always insufficient to interpret different people’s practices, including those of divergent designers, in making futures (Ansari, 2020). Such an approach involves deep reflection in service design communities and questioning regarding “what is known, how is it known, why this known is valued” (Verran, 2018, p. 127). Akama et al. (2019) challenge the notion of a universal model of replicable design processes and the neutral positionality of designers in practice; they suggest accounting for the presence of designers to help reveal the condition that different knowers of service design displace heterogeneity beyond the dominant narrative. Light (2019) explores a “marginal” design narrative to challenge totalizing Western narratives, according to her design experience in northern Finland, geographically on the “margin” of the west. These accounts emphasize the need for greater plurality within the narratives in service design discourse and also point to a way forward.

Methodology

To build an understanding of how the knowers of service design can narrate service design practices in ways that better account for cultural plurality, we investigated and reflected on our practices of telling stories of service design in relation to cultures, by conducting, analyzing, and revisiting interviews. Throughout the process, we paid attention to the concepts employed to tell these stories.

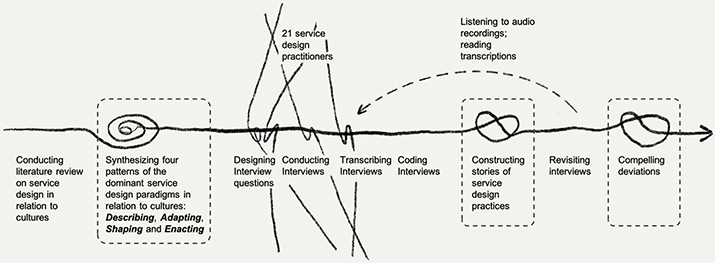

Figure 1 illustrates our study path. We started with a literature review of academic service design discourse to unpack the dominant narrative and view on cultures. Through this process, we synthesized four narrative patterns of service design in relation to cultures, according to the service design themes of describing, shaping, adapting to, and enacting cultures. Along with these patterns, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 21 service design practitioners. We then built stories for each pattern by analyzing and coding the narratives of the interviews. We selected one representative story for each pattern of the dominant narratives and revisited the interviews that contained it. By introducing more of the contexts of practices discussed in the interviews into the scope of our analysis, we examined how cultural plurality is being erased and how it can be restored to include a more decentralized narrative of service design. Noting many criticisms of these four patterns identified by our literature review, we also reflected on the stories through a critical lens.

Figure 1. Overview of our research approach (illustration by the first author).

Unpacking the Dominant Narrative through Interviews

Because different practices enact different realities, the ontology and epistemology of practitioners’ practices are inseparable (Barad, 2007); “it matters what ideas one uses to think other ideas (with)” (Strathern, 1992, p. 10). The interview is a popular way for researchers to build the narrative of other people’s practices (Kvale, 2007). The method often is considered to be rooted in the Western assumption that objective understanding can be acquired through multiple communications of rational individuals (Gobo, 2011). Narrative analysis of interviews often leads to the reconstruction of stories told by different interviewees into a “typical” narrative aligned with one’s knowledge frameworks (Kvale, 2007). Although interviews can be performative because of interviewees’ awareness of the interviewer, such a process can aid in revealing the dominant narrative among practitioners (Alvesson, 2003).

As authors, we also acknowledge that our educational and practical experiences informed the positions from which we chose the interviews and co-constructed the stories. All three authors currently practice and research service design in Europe, with Zhipeng (who conducted the interviews) growing up in China and being educated in service design in English in China, Italy, and Norway; Josina (who reviewed the narratives) growing up in Canada and having over a decade of experience in practicing and researching service design in Canada, the United States, Sweden, and Norway; and Simon (who also reviewed the narratives) being involved in the practice of interaction design and later in service design in Scandinavia since the 1980s. Our experience, the systems we have been socialized into, and our positions have contributed to our reproduction of the dominant service design narrative, as well as to blind spots in our analysis. However, our divergent backgrounds also help us notice some of the taken-for-granted aspects of the dominant service design narrative.

Conducting Interviews According to Literature Review

Before commencing our interviews, we conducted a literature review to examine the manifestation of the dominant service design narrative and determine how it relates to service design and cultures. Our review included 41 articles collected from design journals (e.g., Design Issues, Design and Culture, CoDesign, and International Journal of Design), a prominent academic service design conference (ServDes), and additional articles published in related fields (such as codesign and social innovation). In our sample, we selected not only texts that explicitly discuss culture, but also articles from which cultural factors are taken into account indirectly. For articles with an explicit cultural interest, we analyzed both the narrative (concept, logic, and grammar) of how service design relates to cultures and arguments for service design’s ability to cope with different cultures and practices. For articles that mentioned cultural factors, we mainly focused on the narrative. To avoid oversimplifying the richness of these articles, we condensed each of them into several sentences that described the relationship between service design and culture (see Appendix A). These sentences were aggregated to yield key phrases to illustrate the relationship between service design and culture. By seeking similarities and differences, we synthesized the dominant service design narrative in relation to culture into the four previously mentioned patterns of describing, adapting, shaping, and enacting.

Then, between March and July 2020, Zhipeng conducted one-on-one interviews with 21 service design practitioners, using online video conference platforms such as Zoom and WeChat. Each session was approximately one hour in length. Interactive movement between the analysis of these interviews and the literature review constituted an abductive approach (Dubois & Gadde, 2002). The four patterns that emerged from our literature review conditioned the outline of our interview questions (see Appendix B); we then used the patterns intentionally in subsequent analysis. Thus, we guided interviewees to narrate their design experience from a lens of culture. Their narratives and knowledges of service design practice in multiple cultures did not only arise from their practices but also from our conversation with them. However, we kept the structure of our interviews and analysis loose. For example, we did not define service design and culture in our interviews, and, thus, we encountered many different interpretations of these concepts. These encounters allowed cultural plurality to emerge, in that new knowledge from each participant according to their different experiences was generated (Blaser & De la Cadena, 2018). Common ground dissolved when interviewees reported experiences that did not refer fully to shared service design knowledge and concepts. These experiences or deviations were “burdensome,” in that they needed to be removed when we first coded the interviews to form a unified understanding across different interviews. However, it also were these aspects of the interviews that allowed us to reveal the heterogeneity of practices when we revisited the interviews.

The repertoire of English-language concepts shared by service designers made the interviews with globally divergent practitioners possible. The 21 practitioners in our study come from 12 different countries and practice service design in different locations around the globe. All interviewees were non-native English speakers, but most have received service design education in English in the United Kingdom, United States, Italy, Sweden, China, and Norway. Appendix C presents their detailed backgrounds. Their common mode of education also reflects the shared interest of mainstream knowledge and concepts in service design (Ferruzca et al., 2016). As interviewers and interviewees, we constantly drew on shared service design terms (e.g., workshops, design methods, service journey) as references to build an understanding of service design practices.

Coding Interviews

The analysis of the interviews involved two phases of coding data to capture the concepts to narrate practices (Gioia et al., 2013). Through this process, we identified 55 codes, applied 1,543 times to 1,012 excerpts. We divided these codes into five conceptual groups that consist of the elements of narrative and plots connected with cultural perceptions, perceptions of service design, motivations, practices, and response. For example, the practices code group consists of concepts that describe what service design practitioners do, such as setting visions, building models, and visualizing and facilitating communication. In the second phase, we condensed the meanings of the excerpts in the practices code group to synthesize practices for the four patterns (Kvale, 2007). To narrate these practices, we first reconnected them to other coding groups to enrich the contexts. Then, we referred to these connections with the sentences and phrases we built based on the articles in the literature review. We thus made stories for each pattern drawn from the literature, then chose a representative story that reflected the common pattern and related concepts for each pattern.

Revisiting Interviews

Next, we brought the stories back to the interview transcriptions and audio recordings. We explicitly identified ourselves as the narrators of the stories to demonstrate these four patterns, such that we composed the stories with the facts and orientations we wanted to share (Daitue, 2015). In building these stories, we employed our knowledge to relate people, activities, and things we heard in the interviews to the succession of plots. That is, our focus in revisiting the interviews was reflexive interrogation into how the stories we co-constructed eliminate cultural plurality. We paid particular attention to the concepts we used to signify people and their activities. We also drew criticism of these narratives from literature. This process required us to be vigilant about the service design concepts we take for granted and to refuse to fully attach our logics of service design to the narratives we constructed. Thus, we identified particular contextual deviations from the dominant service design narrative that help accommodate the cultural plurality and heterogeneity of practices already in play in service design practice.

Findings

In this section, we present four patterns of the dominant service design narrative in relation to cultures, according to our literature review. First, describing cultures refers to plots that designers give an account of actors and their cultures through design tools, concepts, and designed ideas of services or products (e.g., Hussain et al., 2012). Second, adapting to cultures refers to designers adjusting their approaches to accommodate cultures less compatible with service design (e.g., Taoka et al., 2018). Third, shaping cultures refers to designers envisaging what cultures could be and embodying the scenario of culture into the solutions they expect to implement (e.g., Dennington, 2018). Fourth, enacting cultures refers to practices that focus on how to proliferate the values and notions of service design (e.g., value cocreation and participatory design) in different contexts (e.g., Bailey, 2012).

In the following subsections, we unpack and examine each pattern. We begin by summarizing related literature and follow with representative stories, with pseudonyms applied to protect the anonymity of interviewees. We italicize some compelling concepts related to different patterns, because these concepts can make our use of mainstream service design knowledge more explicit. Then, we examine how these concepts erase the heterogeneity of practices in our narrative.

Service Design Describing Cultures and Beyond

Service designers often work to delineate people, as a group, according to behavior patterns, notions, beliefs, and social norms of those for whom they are designing. Scholars reinforce the belief that designed service ideas or products should reflect cultural features (e.g., Dennington, 2018; Huang & Deng, 2008; Moalosi et al., 2010). The description of cultures typically appears in the research phase, when service designers seek to build a holistic understanding of people through professional tools, concepts, and logic (e.g., Hussain et al., 2012; Joly et al., 2014). The persona is a typical means of naming a group of people (Holmlid & Evenson, 2008); it is a hypothetical archetype of “real” users or stakeholders that describes their interests, aptitudes, behavior models, and goals (Nielsen, 2004). A persona can represent a protagonist on a storyboard, which is a popular tool for telling a story, often in the form of comic strips that envision reality and the future (Holmlid & Evenson, 2008). The product of description often serves as the representation of reality that service design needs to confront in the design phase that follows. The pattern of describing cultures is manifested in the following story:

Amy’s story: Amy works with nurses, a laboratory technician, and a leader from the medical department in a service design project connected with in vitro fertilization (IVF). The purpose of the project is to improve the user experience of patients by promoting a cultural change inside the department. Following the research phase, she made a presentation of her findings to the whole department. In this presentation, she drew a storyboard to describe the behavior patterns of different roles in the department, including how nurses treat patients, how nurses register the information of patients, and the timing of the entire treatment journey. These activities make up the status quo of the culture of IVF in Norwegian society, which service designers need to address in the design phase that follows.

In Amy’s story, we drew a connection between service design practices, including user interviews and participatory approaches and the presentation of findings. We then inferred that this presentation, based on the research, showed the objective reality of IVF in Norwegian society. The coherence of the plot related to our reference to service design concepts. However, when we revisited our interview with Amy, we realized our story disregarded cultural plurality in two ways. First, it failed to recognize that this description was created according to Amy’s encounters with other participants in the specific context. She had worked constantly to build an understanding of the status quo together with other participants from the department. Although her description reflected preexisting reality, it was a creation of a new reality among participants. For example, in the presentation, Amy printed her sketches and sent them to attendees. She found her storyboard provoked doctors to think about themselves from the patient’s perspective, which sparked reflection. In this case, the design materials helped immerse doctors in the patient experience and context (Yu & Sangiorgi, 2018). According to Amy, the storyboard also had a perspective from the patients, so it was kind of from the patients’ eyes. “It was more seeing [doctors] themselves as the patients see them. I thought that was really interesting, that they started seeing themselves.” That is, shifting perspectives and alien languages enacted a new reality that disrupted doctors’ assumptions of their work (Wetter-Edman et al., 2018).

Second, our interviews failed to capture the changes triggered by the newly enacted reality. In the way we originally narrated the story, people were dehumanized, because it was very difficult to perceive the presence of Amy and other participants involved in service design. It centered the use of service design tools to do research and described others monolithically. To accommodate the change though, the new reality needs to be placed within a meshwork of multiple realities.

Service Design Adapting to Cultures and Beyond

In the dominant narrative, the monolithic view of culture implies that service design fits some cultures better than others. Adapting to culture implies that Western service design approaches can be adjusted to fix multiple cultural contexts, especially non-Western cultures (e.g., Lee & Lee, 2007; Pirinen, 2016). These studies of cultural difference imply that the design approaches in the following story of Claudia involve shifting her approach from a workshop to “informal” interviews to adapt to the culture in Uganda hospitals. By presenting this story, we show how we appropriate design practitioners’ practices into service design terminologies:

Claudia’s Story: Claudia and her cross-disciplinary team work on a healthcare project that aims to deploy remote telemedicine to make healthcare more accessible to patients in Uganda. The design team is based in London. In the research phase, they flew to Uganda to understand both acceptance of the technology and Ugandan doctors’ work routines. Before leaving London, they prepared some materials and planned to run several workshops in Ugandan hospitals, in the same way they had in healthcare organizations in the United Kingdom. However, no doctors or nurses in Ugandan hospitals wanted to attend. People refused to express any opinions about their workspaces and expressed fear about saying the wrong things; the team tried to adapt by conducting one-on-one interviews and observations. However, the behavior of the doctors they were shadowing were noticeably altered by their presence as foreign designers. As a result, Claudia conducted interviews in an informal way. For instance, she invited doctors or nurses to have coffee or lunch with her to collect information about how they work in the hospital. Because this is a typical way that Ugandan doctors make friends at work, she changed the setting and tone of the interviews to make them more informal.

The story of adapting to cultures can contribute to the centrality of service design knowledge and praxis, whereas other practices in cultural plurality tend to be marginalized in narrative. The term adapting to cultures indicates a parallel purpose of maintaining the epistemological stability of a service design approach. In Claudia’s story, we tended to attribute the peculiarities of participants’ reluctance as local culture, rather than questioning whether mainstream service design knowledge was suitable in this context. In fact, without the careful exploration directly with the people participating, we do not know how the reaction to a strange design approach is related to their cultures. The tendentious attribution is manifested in other studies that focus on non-Western practices (e.g., Hussain et al., 2012; Taoka et al., 2018). The narrative of adaptation potentially encourages localizing designs to adopt Western service design as a criterion (Akama, 2009; Akama & Yee, 2016; Kang, 2016).

Moreover, the centralization of service design knowledge is reflected in the neglect of non-service design practices of service designers (also see Akama et al., 2019). We framed Claudia’s practices of developing friendships with doctors as informal interviews, with an assumption that everything Claudia did was service design. By doing so, lunch, coffee, and personal conversations become a technique of doing interviews with the goal of collecting data. However, what service design practitioners do with their on-site experience and reflexivity goes beyond the scope of service design. For example, in Claudia’s practice she gradually recognized that the divergence between the project team and local people was too big to explain:

“They [the nurses] really believed that this [telemedicine] wasn’t going to work because they have seen in many of the patients from rural areas the way they react to very simple technology. They really don’t want to be near a machine because there’s the perception that if I actually get to the point that I need to go to a hospital and I actually need to use a machine, I’m going to die. If you bring a machine to their community, it’s actually almost like bringing death.”

By acknowledging this divergence, their focus shifted from improving the accessibility of telemedicine to understanding why technology scares them. Claudia felt it was necessary to understand participants’ deeper life experiences beyond what they interpreted as confrontational interrogation. To do so, she chose to take a more passive and respectful approach, by listening and talking, rather than overtly inquiring about something in particular. She even had an argument with other team members when they asked her to be more proactive and inquisitive.

Service Design Shaping Cultures and Beyond

As a discipline that attaches great importance to transformation, service design often regards a lasting change in culture, including the behaviors and value propositions of groups of people, as a key purpose (e.g., Jensen et al., 2017; Sangiorgi, 2011). Service designers tend to envisage what culture could be according to their understanding of existing cultures and to create scenarios of ideal cultures as the purpose of the practice. Shaping cultures reflects teleology in design, such that its practices are intentional operations for a specific purpose (Buchanan, 1992). In service design, building and implementing a solution is a crucial agency of the teleology. For example, Dennington (2018) suggests service design is capable of changing and making cultures, and also proposes an approach to capture cultural trends from cultural phenomena and translate them into service solutions that promote cultural change. In many service design frameworks (e.g., Double Diamond), the success and failure of implementing solutions represents the sole outcome of service design stories. Yiyun’s story shows how a solution that addresses problems and needs defined in previous design practices failed to be implemented:

Yiyun’s story: After months of research at a community in Huangshan, China, Yiyun found there were a lot of resources in the community, such as a reading room and activity room, that community workers were not utilizing fully. She hoped to find a way to integrate design thinking to the work of the social workers. Her solution was a set of desktop card-based tools. Yiyun used cards to present various resources owned by the community as well as various residences in community. There was a paper map showing an empty journey map; the map was similar to the user journey map but was changed according to the context of community. This map and cards were intended to help social workers engage local residents to cocreate community activities. Much to Yiyun’s regret, after she delivered the tool to community members, they did not use it. Yiyun assumed her process failed. When she reflected, she thought she should have done more research about how to sustain the use of this tool in the community.

For Yiyun, the implementation of the solution was always a distant goal. Yiyun’s sense of failure grew from the tool she delivered not being used by social workers. During our interview, Yiyun raised doubts about the ability of service design to shape cultures. When she reflected on her project, she mentioned, “the change of culture is a long-term process, rather than a temporary process or a project.” She shared that she thought the intervention of designers is relatively very short: “When a service designer leaves the community and the project is completed for a month or a year, maybe the project will be completely forgotten by the culture.”

Her thoughts led us to question whether the achievement of a specific purpose, especially the implementation of a solution, fully explains how service design influences cultures. Does this narrative explain those micro influences away, leaving only a rough conclusion of success or failure in shaping cultures? When revisiting the interview, we tried to focus on the changes that Yiyun perceived in this project. We found the community workers still have Yiyun’s tool; they are proud of it and happily present it to others. We failed to pursue the reason for their pride. If we can accommodate these phenomena in the narratives of service design, we might make stories more open-ended and lead to different futures, rather than ending them with failure of implementation.

Service Design Enacting Cultures and Beyond

The monolithic view of culture also is manifested in the self-reproduction of common characteristics of service design practice, which is a process of enacting culture, especially design culture. The concept of design culture in the narrative designates distinct contemporary manifestations of the design practice of designers and other actors (Julier & Munch, 2019). Enacting design culture indicates that service design can display and spread particular values and meanings of culture held by service designers. Service designers are expected to perform their profession and gain legitimacy by employing specific behavior patterns, a particular language, and similar value propositions (Fayard et al., 2017). For example, design culture often is thought to involve a radical participatory democracy that encourages diverse actors to design and provide solutions to address specific problems (Manzini, 2016). The following story of Songhwa illustrates that service design practitioners are enacting a design culture. When coding our interviews, we regarded this story as evidence of service design displaying a particular value of participation by setting the rules and rituals of participants’ behaviors in the workshop. However, we realized that in the narrative of service design practice, the culture and politics of service design is difficult to perceive:

Songhwa’s story: In a project of organizational transformation, Songhwa and her service design team invited employees from a large South Korean company to attend a codesign workshop. Because this workshop was in the early research phase, the purpose was to investigate the status quo of the company. The design team thought the company had a “conservative and hierarchical” culture, and employees might not adapt well to the codesign workshop. To counterbalance this culture, the design team built rituals to ask participants to act differently. For instance, they asked participants to call each other by their first names, rather than surnames with job title, in their everyday work. By doing so, they helped participants offset their behaviors and perceptions by exposing them to new possible meanings. This shift of form of address is very helpful in making different people from different hierarchical positions communicate directly in the workshop.

In this story, we did not use a term such as design culture to summarize design practice, as what we do to others’ collective features in the above stories. The concepts relating to the South Korean company and employees tend to be monolithic (conservative and hierarchical culture, behaviors and perceptions of employees, status quo of the company), whereas the concepts of service design tend to be instrumental and functional (e.g., purpose of the workshop, building rituals) to condition the activities of service design practitioners. These two tendencies are interrelated. To give exclusive attention to the functionality of service design, it is necessary to neutralize its value proposition and objectify other practices (Akama et al., 2019; Janzer & Weinstein, 2014).

However, when revisiting the interview with Songhwa, we found she was aware of the power dynamic in the global social construction of service design knowledge. In the construction of the story, we ignored her positionality in this practice. She told us she temporarily works for a European service design consultancy, and the South Korean company is its client. Because of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the two companies work remotely. She shared that she is the person who runs the workshop directly with the client in South Korea, with the designer in Europe taking responsibility for organizing the workshop remotely. She is confused about this situation, because in past few years, she found that many local service design consultancies in South Korea had gone bankrupt, because the clients do not accept their practices of service design: “I would say ‘hiring the UK company’ is stupid is because I’m South Korean and I can do this kind of project in South Korea for your company but why are you asking a company in London?”

Departing from the Dominant Narrative

Narratives of service design that account for cultural plurality matter, because they are attempts to grasp the relationality of service design to different practices encountered in making futures. According to our examination of the four patterns of service design, we find the dominant service design narrative fails to integrate its practice with other practices but instead pours different practices into one container. First, in the story of service design, describing cultures can enact a new reality. However, it often is overlooked that this reality is enacted in the context of the encounter between designers and other participants. Moreover, the reality fails to be combined with other realities; it risks becoming universal and concealing other realities. Second, the plot of adapting to cultures tends to designate the peculiarities of people’s poor fitness to participate in the service design as their culture. Adapting to cultures encourages service designers to over-establish themselves as experts while ignoring their own non-service design practices. Third, shaping of cultures implies a detached, exclusive position of building solutions in narrating the influence of service design, failing to notice other influences of service design. Fourth, the story often regards service design as an instrument for other cultures but is insensitive and oblivious to the power dynamics and cultural values it enacts.

Discussion

Through careful analysis of the dominant service design narrative in relation to culture and the deviations from the common patterns of this narrative, our study makes two key contributions. First, it demonstrates the insufficiency of the dominant narrative to capture the differences of service design in multiple cultures and to recognize the risks associated with this oversimplified story. Second, it encourages service design knowers to decentralize service design within the narrative, by acknowledging more fully the diverse practices of world-making with which it is entangled.

Insufficiencies of the Dominant Narrative

Service design often is devoted to integrating the needs, perspectives, concepts, and methods of different actors, then collaboratively prompting transformative innovation (Yu, 2020). The concept of cultural plurality reminds us that the value of co-creation in service design implies an ethical commitment that different practices can and must coexist. Service design involves not only the manipulation of the different characteristics of people to achieve one purpose but also the accommodation of multiple forms of making futures. We argue that this commitment has not been fulfilled. Our concern about the dominant narrative resonates with Fry et al.’s (2015) ideas about the defuturing effects of design; they suggest that possible futures are systemically eliminated by existing design practices. Existing knowledge becomes a “refuge” from what is actually happening (Ingold, 2018, p. 9). The crisis of the service design narrative is its incapacity to interpret other practices of making futures, other than translating them into the knowledge of service design. This tendency restricts the fluidity of service design and, when other practices are assimilated into service design, it restricts service design from benefiting from other knowledge and wisdom.

To account for cultural plurality and restore the imagination of service design praxis and knowledge, we argue that decentralizing the dominant narrative can act as a starting point. Although the dominant narrative demonstrates the power of mainstream service design knowledge through its central positioning, assimilation, and marginalization of heterogeneous practices, this narrative cannot fully cancel out all the entangled heterogeneous practices; everyday practices are quietly woven around the dominant narrative through subtle slippages (De Certeau, 1997). This study presents a glimpse into some of the heterogeneous practices in daily life in which service design practitioners’ backgrounds, reflexivity, and bravery disclose more imagination of the future. We advance Akama and Yee’s (2016) argument that designing happens in other names, conditioned by various localities; the practice of making futures does not always need to be fully named as designing. That is, the logic and coherence of service design can be disturbed, due to the contamination and attunement with other cultures (Light, 2019; Tsing, 2015).

Enabling Narrative Sensitivity

Our paper clearly emphasizes the significance of narrative in decolonizing the knowledge and praxis of service design. According to this proposition, our main contribution is to propose four patterns that unpack the dominant service design narrative in relation to culture. By examining and reflecting on these patterns, we elaborate how the dominant narrative conceals and marginalizes cultural plurality. We hope these findings encourage knowers to explore how to entangle the story of service design with other practices. We believe it is necessary to cultivate a narrative sensitivity and vigilance regarding the presence of mainstream service design knowledge.

As we argued from the beginning, service design concepts are the world-making tools for knowledge. We, knowers of service design, must sensitize ourselves to the concepts of service design, especially those essential but sometimes unexamined concepts that underlie our narratives. In the stories we co-constructed, we found ourselves citing our concepts too broadly when referring to other practices. On the one hand, there is an urgent need to be more cautious around the use of concepts labeling culture. Labeling the difference encountered in design practices as a culture without careful examination may conceal the power dynamics and tensions in the practices (Breidenbach & Nyíri, 2011), and undermine complex and relational values and meanings which contain transformative messages connecting to histories and philosophies of the localities (Akama et al., 2019). The methods for conducting interviews with design practitioners in this paper are demonstrated to be insufficient and even problematic to achieve grappling with this complexity, since focusing the interviews on cultures may encourage interviewees to label cultural concepts to the peculiar phenomena they encounter. On the other hand, considering the wide range of concepts in service design that have not been carefully examined, such as user, service delivery process, and stakeholder, we need to form our narratives more carefully. For instance, Kim (2018) focuses on the Western history of the fundamental concept of service, suggesting that the contemporary service concept is often determined by the principles of business. Suchman (2021) questions whether the concept of design over-occupies the discourse of general practices of making. This question resonates with the ontological turn in design (e.g., Escobar, 2018; Willis, 2006). We thus call for study and practice to examine and challenge the widely used concepts of mainstream service design in narrating the relationality among design, history, and the future of people.

For service design, this narrative sensitivity also touches on how we think of relationality. There is a preference for holistic thinking in service design, through which designers can build a unified understanding that connects the practices of different stakeholders. Anthropologist Tsing (2015) suggests that framing different practices by prefabrication—that is, the logic that various practices happen to achieve a common purpose—is not enough. The knowers of service design also must see a juxtaposition, a coming together of an assembly of unintentional coordination through which multidirectional change happens. Therefore, the narrative of service design practices should strive to remain open-ended, because these practices exist in evolving contexts in which design and other practices are ongoing (Vink et al., 2021). Accordingly, the scope of the design narrative can be expanded to “what constitutes transformative change and how it happens” (Suchman, 2011, p. 3), rather than how design methods are used. According to our interviews, which focus only on the narratives of service design practitioners, the stories in this study fail to capture the presence of other people. Too often the narrators of service design are considered the only knowers, even though other people are involved in diverse ways. Therefore, we also call for further ethnographic studies of how participants narrate service design according to the threads of their lives.

Conclusion

We raise a concern regarding service design knowers’ capacity to build narratives in a process of world-making. With this study, we propose that acknowledging cultural plurality as an a priori condition represents care for people and cultures at the “margin” and their ability to make futures that are divergent and not fully comparable. The ways in which paths toward futures are narrated is becoming even more crucial. Service design knowledge constructs the dominant narrative to describe knowers’ and others’ practices of creating the future. By reflecting on our own experiences of narrative practice, we realize that our knowledge is capable of constantly reinstating itself by translating the practice of different people into a cohesive, recognizable service design practice. For knowers of service design, this translation encourages positioning themselves as service design experts, and as experts, all one’s practices are service design practices that restrain the perception of heterogeneities beyond the scope of mainstream service design knowledge. For participants in service design, the dominant narrative risks translating practices into only one part of service design, by grouping them according to a monolithic cultural view. By revisiting our interviews, we shed light on neglected practices that question the sufficiency of the dominant narrative and begin to focus our attention on how we can better narrate cultural plurality and depart from the dominant narrative. We suggest a commitment to narrative sensitivity that attends to the translation of service design knowledge and concepts. Moreover, we encourage service designers to refuse sole reference to mainstream service design knowledge and welcome entanglements with heterogeneous practices that might foreshadow more divergent futures.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the designers interviewed as part of this project who generously shared their experiences with us. We also express our deep gratitude to Yoko Akama, all of the guest editors, and the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable and thorough feedback on this manuscript; and to Christoph Brumann and Joost Beuving for their input that helped to clarify our argument. This project has received funding from the Research Council of Norway through the Centre for Connected Care (C3).

References

- Aguirre, M. (2020). Transforming public organizations into co-designing cultures: A study of capacity-building programs as learning ecosystems (Doctoral dissertation). Oslo School of Architecture and Design, Oslo, Norway.

- Akama, Y. (2009). Warts-and-all: The real practice of service design. In Proceedings of the 1st Nordic Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation (pp. 1-11). Linköping, Sweden: Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Akama, Y., Hagen, P., & Whaanga-Schollum, D. (2019). Problematizing replicable design to practice respectful, reciprocal, and relational co-designing with indigenous people. Design and Culture, 11(1), 59-84. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2019.1571306

- Akama, Y., & Yee, J. (2016). Seeking stronger plurality: Intimacy and integrity in designing for social innovation. In Proceedings of the Cumulus Conference on Open Design for E-very-thing (pp. 173-180). Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong Design Institute.

- Alvesson, M. (2003). Beyond neopositivists, romantics, and localists: A reflexive approach to interviews in organizational research. Academy of Management Review, 28(1), 13-33. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040687

- Ansari, A. (2020). Plural bodies, pluriversal humans: Questioning the ontology of ‘body’ in design. Somatechnics, 10(3), 286-305. https://doi.org/10.3366/soma.2020.0324

- Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bailey, S. G. (2012). Embedding service design: The long and the short of it. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation (pp. 31-41). Linköping, Sweden: Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Blaser, M., & De la Cadena, M. (2018). Pluriverse: Proposals for a world of many worlds. In M. de la Caden & M. Blaser (Eds.), A world of many worlds (pp. 1-22). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Breidenbach, J., & Nyíri, P. (2011). Seeing culture everywhere: From genocide to consumer habits. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Brumann, C. (1999). Writing for culture: Why a successful concept should not be discarded. Current Anthropology, 40(S1), S1-S27. https://doi.org/10.1086/200058

- Buchanan, R. (1992). Wicked problems in design thinking. Design Issues, 8(2), 5-21. http://doi.org/10.2307/1511637

- Daiute, C. (2015). Narrating possibility. In G. Marsico (Eds.), Jerome S. Bruner beyond 100 (pp. 157-172). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- De Certeau, M. (1997). Culture in the plural (T. Conley, Trans.). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published 1974)

- Dennington, C. (2018). Trendslation—An experiential method for semantic translation in service design. In Proceedings of the Conference on Service Design Proof of Concept (pp. 1049-1063). Linköping, Sweden: Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Dubois, A., & Gadde, L. E. (2002). Systematic combining: An abductive approach to case research. Journal of Business Research, 55(7), 553-560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8

- Eriksen, T. H. (2001). Small places, large issues: An introduction to social and cultural anthropology. London, UK: Pluto Press.

- Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the pluriverse: Radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Fayard, A. L., Stigliani, I., & Bechky, B. A. (2017). How nascent occupations construct a mandate: The case of service designers’ ethos. Administrative Science Quarterly, 62(2), 270-303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839216665805

- Ferruzca, M., Tossavainen, P., Kaartti, V., & Santonen, T. (2016). A comparative study of service design programs in higher education. In Proceedings of the 10th Annual International Technology, Education and Development Conference (9 pages). Valencia, Spain: IATED. https://doi.org/10.21125/inted.2016.0531

- Fry, T., Dilnot, C., & Stewart, S. (2015). Design and the question of history. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Gobo, G. (2011). Glocalizing methodology? The encounter between local methodologies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 14(6), 417-437. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2011.611379

- Goodman, N. (1978). Ways of worldmaking (Vol. 51). Cambridge, MA: Hackett Publishing.

- Holmlid, S., & Evenson, S. (2008). Bringing service design to service sciences, management and engineering. In B. Hefley & W. Murphy (Eds.), Service science, management and engineering education for the 21st century (pp. 341-345). Boston, MA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-76578-5_50

- Huang, K. H., & Deng, Y. S. (2008). Social interaction design in cultural context: A case study of a traditional social activity. International Journal of Design, 2(2), 81-96.

- Hussain, S., Sanders, E. B. N., & Steinert, M. (2012). Participatory design with marginalized people in developing countries: Challenges and opportunities experienced in a field study in Cambodia. International Journal of Design, 6(2), 91-109.

- Ingold, T. (2007). Lines: A brief history. London, UK: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. (2018). Anthropology: Why it matters. Hoboken, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Janzer, C. L., & Weinstein, L. S. (2014). Social design and neocolonialism. Design and Culture, 6(3), 327-343. https://doi.org/10.2752/175613114X14105155617429

- Jensen, M. B., Elverum, C. W., & Steinert, M. (2017). Eliciting unknown unknowns with prototypes: Introducing prototrials and prototrial-driven cultures. Design Studies, 49, 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2016.12.002

- Joly, M., Cipolla, C., & Manzini, E. (2014). Informal; formal; collaborative: Identifying new models of services within favelas of Rio de Janeiro. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation (pp. 57-66). Linköping, Sweden: Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Julier, G., & Munch, A. (2019). Introducing design culture. In G. Julier, M. N. Folkmann, N. P. Skou, H. C. Jensen, & A. V. Munch (Eds.), Design culture: Objects and approaches (pp. 1-11). London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Junginger, S. (2015). Organizational design legacies and service design. The Design Journal, 18(2), 209-226. https://doi.org/10.2752/175630615X14212498964277

- Kang, L. (2016). Social design as a creative device in developing Countries: The case of a handcraft pottery community in Cambodia. International Journal of Design, 10(3), 65-74.

- Kim, M. (2018). An inquiry into the nature of service: A historical overview (part 1). Design Issues, 34(2), 31-47. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00484

- Kurtmollaiev, S., Fjuk, A., Pedersen, P. E., Clatworthy, S., & Kvale, K. (2018). Organizational transformation through service design: The institutional logics perspective. Journal of Service Research, 21(1), 59-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670517738371

- Kvale, S. (2007). Analyzing interviews. In S. Brinkmann & S. Kvale (Eds.), Doing interviews (pp. 102-120). London, UK: Sage. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781529716665.n9

- Law, J. (2015). What’s wrong with a one-world world? Distinktion: Scandinavian Journal of Social Theory, 16(1), 126-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/1600910X.2015.1020066

- Law, J., & Lien, M. (2018). Denaturalizing nature. In M. de la Caden & M. Blaser (Eds.), A world of many worlds (pp. 131-171). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Lee, J. J., & Lee, K. P. (2007). Cultural differences and design methods for user experience research: Dutch and Korean participants compared. In Proceedings of the Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces (pp. 21-34). New York, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1314161.1314164

- Light, A. (2019). Design and social innovation at the margins: Finding and making cultures of plurality. Design and Culture, 11(1), 13-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2019.1567985

- Mahamuni, R., Lobo, S., & Das, B. (2020). Proliferating service design in a large multi-cultural IT organization–An inside-out approach. In Proceedings of the Conference on Tensions, Paradoxes and Plurality (pp. 34-35). Linköping, Sweden: Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Malmberg, L. (2017). Building design capability in the public sector: Expanding the horizons of development (Doctoral dissertation). Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden.

- Manzini, E. (2016). Design culture and dialogic design. Design Issues, 32(1), 52-59. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00364

- Matthews, T., Judge, T., & Whittaker, S. (2012). How do designers and user experience professionals actually perceive and use personas? In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1219-1228). New York, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2207676.2208573

- Moalosi, R., Popovic, V., & Hickling-Hudson, A. (2010). Culture-orientated product design. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 20(2), 175-190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-008-9069-1

- Nielsen, L. (2004). Engaging personas and narrative scenarios (Doctoral dissertation). Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Otto, T., & Bubandt, N. (2010). Beyond the whole in ethnographic practice? Introduction to part 1. In T. Otto & N. Bubandt (Eds.), Experiments in holism: Theory and practice in contemporary anthropology (pp. 19-27). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444324426.ch2

- Pirinen, A. (2016). The barriers and enablers of co-design for services. International Journal of Design, 10(3), 27-42.

- Rauth, I., Carlgren, L., & Elmquist, M. (2014). Making it happen: Legitimizing design thinking in large organizations. Design Management Journal, 9(1), 47-60. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmj.12015

- Ruigrok, W., & Achtenhagen, L. (1999). Organizational culture and the transformation towards new forms of organizing. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(4), 521-536. https://doi.org/10.1080/135943299398140

- Sangiorgi, D. (2011), Transformative services and transformation design. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 29-40.

- Seidelin, C., Sivertsen, S. M., & Dittrich, Y. (2020). Designing an organisation’s design culture: How appropriation of service design tools and methods cultivates sustainable design capabilities in SMEs. In Proceedings of the Conference on Tensions, Paradoxes and Plurality (pp. 11-31). Linköping, Sweden: Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Stengers, I. (2018). The challenge of ontological politics. In M. de la Caden & M. Blaser (Eds.), A world of many worlds (pp. 83-111). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Strathern, M. (1992). Reproducing the future: Essays on anthropology, kinship and the new reproductive technologies. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Strathern, M. (2018). Opening up relations. In M. de la Caden & M. Blaser (Eds.), A world of many worlds (pp. 23-52). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Stuart, F. I. (1998). The influence of organizational culture and internal politics on new service design and introduction. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 9(5), 469-485. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564239810238866

- Suchman, L. (2011). Anthropological relocations and the limits of design. Annual Review of Anthropology, 40, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.041608.105640

- Suchman, L. (2021). Border thinking about anthropologies/designs. In K. Murphy & E. Wilf (Eds.), Designs and anthropologies: Frictions and affinities (pp. 17-34). Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

- Taoka, Y., Kagohashi, K., & Mougenot, C. (2018). A cross-cultural study of co-design: The impact of power distance on group dynamics in Japan. CoDesign, 17(1), 22-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1546321

- Tlostanova, M. (2017). On decolonizing design. Design Philosophy Papers, 15(1), 51-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/14487136.2017.1301017

- Tsing, A. L. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Verran, H. (2018). The politics of working cosmologies together while keeping them separate. In M. de la Caden & M. Blaser (Eds.), A world of many worlds (pp. 112-130). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Vink, J., Koskela-Huotari, K., Tronvoll, B., Edvardsson, B., & Wetter-Edman, K. (2021). Service ecosystem design: Propositions, process model, and future research agenda. Journal of Service Research, 24(2), 168-186. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520952537

- Wetter-Edman, K., Vink, J., & Blomkvist, J. (2018). Staging aesthetic disruption through design methods for service innovation. Design Studies, 55, 5-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2017.11.007

- Willis, A. M. (2006). Ontological designing. Design Philosophy Papers, 4(2), 69-92. https://doi.org/10.2752/144871306X13966268131514

- Yu, E. (2020). Toward an integrative service design framework and future agendas. Design Issues, 36(2), 41-57. https://doi.org/10.1162/desi_a_00589

- Yu, E., & Sangiorgi, D. (2018). Exploring the transformative impacts of service design: The role of designer–client relationships in the service development process. Design Studies, 55, 79-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2017.09.001

Appendix A. Selected Articles for Literature Review

| Articles | How design or service design relates to culture(s)? | Is culture a subject in the article? | Patterns of the dominant narrative |

| Akama, Y. (2009). Warts-and-all: The real practice of service design. In Proceedings of the ServDes Conference on DeThinking Service; ReThinking Design (pp. 1-11). Linköping, Sweden: Linköping University Electronic Press. | The paper critiques service design practices in Australia that are often documented and reported in a European manner as obstacles to contextual understanding the practice of service design. | Yes | Adapting to cultures |

| Akama, Y., Hagen, P., & Whaanga-Schollum, D. (2019). Problematizing replicable design to practice respectful, reciprocal, and relational co-designing with indigenous people. Design and Culture, 11(1), 59-84. | This paper criticizes the replicability of globally popular methods of design as well as their colonial legacies. The authors propose respectful, reciprocal, and relational approaches as an ontological commitment of co-design. The paper also encourages designers to cultivate a sensitivity to locality, culture, value, and knowledge in their practices. | Yes | Enacting cultures |

| Aldersey-Williams, H. (1990). Design and cultural identity. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 1(2), 69-74. | The design has the responsibility to resist the global “cultural imperialism”. In practice, design needs to display cultural identity, especially regional cultural identity. | Yes | Describing cultures; Enacting cultures |

| Baek, J. S., Kim, S., Pahk, Y., & Manzini, E. (2018). A sociotechnical framework for the design of collaborative services. Design Studies, 55, 54-78. | In the Discussion, the authors refer McDonaldization to as dehumanized modern services, which appears in the culture of a rationalized society (p.71). | No | Describing cultures |

| Baek, J. S., Kim, S., & Harimoto, T. (2019). The effect of cultural differences on a distant collaboration for social innovation: A case study of designing for precision farming in Myanmar and South Korea. Design and Culture, 11(1), 37-58. | This paper explores the influence of cultural differences encountered in the collaboration between Myanmar Social Enterprise and South Korean University in a design project of Soil Sensors and related Services. By reflecting upon the process and outcomes, they highlight the cultural gaps observed and how they were reinforced or bridged during the collaboration across distance. The authors also emphasize the need for designers to be more sensitive about the cultural difference, especially the invisible and potential needs, values, and notions of users and other actors. | Yes | Describing cultures; Adapting to cultures |

| Bailey, S. G. (2012). Embedding service design: The long and the short of it. In Proceedings of the 3rd Service Design and Service Innovation Conference (pp. 31-41). Linköping, Sweden: Linköping University Electronic Press. | This paper suggests that the embedding of design methods, practices, and cultures into organizations requires conceptual changes in culture and behavior. In the author’s fieldwork, employees’ change in language and behavior toward design can be initiated by raising awareness of design practices and being engaged in design projects or workshops. | Yes | Enacting cultures |

| Bowen, S., McSeveny, K., Lockley, E., Wolstenholme, D., Cobb, M., & Dearden, A. (2013). How was it for you? Experiences of participatory design in the UK health service. CoDesign, 9(4), 230-246. | This paper mentions that in healthcare services and NHS Hospitals there are some distinctive cultural settings to which participatory design needs to adapt (p. 231). In the Discussion, this paper uses the institutional culture of participation as a future vision to illustrate that the participatory approach needs to be better embedded in organizations. | No | Adapting to cultures; Enacting cultures |

| Christensen, B. T., & Ball, L. J. (2018). Fluctuating epistemic uncertainty in a design team as a metacognitive driver for creative cognitive processes. CoDesign, 14(2), 133-152. | This paper focuses on how Scandinavian design teams understand and design for Chinese users and suggests that the cross-cultural interpretation is unstable and vague, while the uncertainty also reflects the creative potential of design. | Yes | Adapting to cultures |

| Clemmensen, T., Ranjan, A., & Bødker, M. B. (2017). How cultural knowledge shapes design thinking: A situation-specific analysis of availability, accessibility and applicability of cultural knowledge in inductive, deductive and abductive reasoning in two design debriefing sessions. In B. T. Christensen, L. J. Ball, & K. Halskov (Eds.), Analysing design thinking: Studies of cross-cultural co-creation (pp. 153-171). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. | This paper questions the homogeneity and unity in design thinking, and holds that the thinking of designers and consultants is often biased by their cultural knowledge. The study adopts region and country as important criteria to classify cultures. | Yes | Adapting to cultures |

| Denington, C. (2018). Trendslation–An experiential method for semantic translation in service design. In Proceedings of the Conference on Service Design Proof of Concept (pp. 1049-1063). Linköping, Sweden: Linköping University Electronic Press. | This paper discusses the potential role of service design as a cultural intermediary. In service design practices, cultural materials and phenomena can be translated into new service offerings and details. | Yes | Describing cultures; Shaping cultures; Enacting cultures |