The Work of Democratized Design in Setting-up a Hosted Citizen-Designer Community

Sampsa Hyysalo 1,*, Virve Hyysalo 2,3, and Louna Hakkarainen 1

1 School of Art, Design and Architecture, Department of Design, Aalto University, Espoo, Finland

2 City of Helsinki, Culture and Leisure Sector, Helsinki, Finland

3 Faculty of Art and Design, University of Lapland, Rovaniemi, Finland

The types of work going into participatory and community forms of design is an emerging research area that complements participatory design’s earlier emphasis on the ideals and principles of democratic design. This article documents a year-long process wherein a hosted citizen-designer community was initiated to contribute to the design of a large public space its services: Helsinki Central Library Oodi. We examine the types of work designers in the host organization engaged in to accomplish the set-up and initiation of the hosted citizen-designer community. In so doing we examine how views of design democracy and practical considerations permeate each other in the realization of the hosted community.

Keywords – Collaborative Design, Public Sector, Design Democracy, Pragmatics.

Relevance to Design Practice – Project pragmatics are an important constituent of succeeding in collaborative design. The article helps in recognizing the types of work that are necessary for successful designer-user community building and the handling of trade-offs that necessarily characterize the process. It also offers a rare detailed case study view into what it takes to set up a user-designer community for a large-scale project.

Citation: Hyysalo, S., Hyysalo, V., & Hakkarainen, L. (2019). The work of democratized design in setting-up a hosted citizen-designer community. International Journal of Design, 13(1), 69-82.

Received May 14, 2018; Accepted March 25, 2019; Published April 30, 2019.

Copyright: © 2019 Hyysalo, Hyysalo, & Hakkarainen. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

*Corresponding Author: sampsa.hyysalo@aalto.fi

Sampsa Hyysalo is a professor of CoDesign in the Department of Design, Aalto University. His research focuses on the interplay between designers and users in the development of new products and services. His work combines design research, science & technology studies, and innovation studies. He has published approximately 70 articles and book chapters and a handful of books, the latest being “The new production of users: Changing innovation communities and involvement strategies” (with Elgaard Jensen and Oudshoorn, Routledge, 2016).

Virve Hyysalo is working at Helsinki City as a participation specialist. Her responsibilities include engaging citizens and partners in the design of the cultural and recreational services of the future. Her interests include co-design, service design, public participation and open democracy. She believes that design-based approaches can help the public sector to improve its services and address social issues. She is also pursuing her PhD on how public cultural services can be reshaped by engaging citizens in co-creation.

Louna Hakkarainen is a senior researcher working at Women’s Line Finland. Her PhD study focused on the evolution of collaboration in living labs and in user driven innovation and combined design research and science and technology studies. Currently Hakkarainen’s work engages with the intersections of gender-based violence and digital technologies.

Introduction

Various forms of communities wherein users become (co-)designers—such as user groups, citizen boards, consumer panels, living labs, and user innovation communities—are increasingly common features in development activities. Products, services and public spaces alike are developed with the help of their end users in these formations, which we call user-designer communities. To date, the dominant focus of research has been on what user-design communities can or could enable, be this citizen empowerment, design participation or innovation outcomes (Benkler, 2006; Robertson & Simonsen, 2012; von Hippel, 2005, 2016), or equally, focusing on the exploitation of citizens’ creativity (Thrift, 2006).

Recent research, however, has started to enquire into how user-designer communities work in the first instance. Good examples of this shift can be found in studies by Verhaegh van Oost and Oudshoorn (2016) on the kind of work that is needed to run a community innovation; Bødker, Dindler, and Iversen, (2017) on the infrastructuring work for participatory design (PD); and Mozaffar (2016) on how software user groups rely on blending multiple activities and benefits for their participants. This analytical focus is motivated by broader recognition that the realization of collaborative design projects outside sheltered academic settings has become ill-documented and analyzed (Shapiro, 2010; Steen, 2011; Jensen & Petersen, 2016). Shapiro further argues that particularly lacking are studies that examine the realization of the full scope of citizen engagement in a project and do not focus on just one or other narrow aspect within it. This entails shifting focus from principles, ideals and methods towards the arrangements, which help users to become more productive while producing more meaningful contributions (Steen, Manchot, & Koning, 2011; Pirinen, 2014; Hyysalo & Hyysalo, 2018; Pinch, 2016; Jensen & Petersen, 2016).

Continuing this line of research, the present paper examines an effort to initiate and retain a ‘hosted’ user-designer community of Helsinki citizens in order to support a large public project—Helsinki Central Library Oodi (from here on CeLib)—a €100 million flagship that seeks to reinvent what public libraries, open citizen spaces and public support for cultural production and consumption will be in the 2020s. Our guiding research questions are:

- What work do host organization participatory designers put into setting up a user-designer community?

- How do the different ideas of design democracy affect the set-up of such a community, and how are their differences resolved in practice?

In section 2, we examine the research on user-designer communities and then, in section 3, outline our research set-up. In section 4, we examine the context of the user community called Friends of the Central Library (FCL) and discuss it in detail in five subsections of section 5, followed by discussion and conclusions.

User-Designer Communities and Design Democracy

Academic interest in user-designer communities grew with the proliferation of open source software communities during the 2000s (Benkler, 2006; Freeman, 2011; Raymond, 2001; Tapscott & Williams, 2008) and gained further momentum from self-organized design in non-digital settings as well (see e.g. Antorini, 2007; Luthje, 2004; Luthje, Herstatt, & von Hippel, 2005; Hyysalo, Elgaard Jenssen, & Oudshoorn, 2016). Several disciplines have addressed user-designer communities (Holmström, 2004; Holmström & Henfridsson, 2006; Tomes, Armstrong, & Clark, 1996), and for us here, user innovation research, PD and science and technology studies (S&TS) are the most relevant fields. User innovation research has most extensively conceptualized user innovation communities; PD has elaborated on the underpinnings involved in design democracy; and S&TS has studied the factual realization of these community forms.

User innovation research looked at open source software communities as model social forms for other settings where citizens and professionals self-organize to innovate for themselves, by themselves (von Hippel, 2001). The pooling of competences and freely revealing designs were found to be common among various sportsmen and other hobbyists (see e.g., Hienerth, 2006; Hyysalo, 2009; Luthje, 2004; Luthje, Herstatt, & von Hippel, 2005; Hyysalo et al. 2013; Hyysalo, Johnson, & Juntunen, 2017) and people who innovated to advance their professional tools (see e.g., Lettl, Herstatt, & Gemunden, 2006; Riggs & von Hippel, 1994). Such communities were seen as important substrata for both democratizing innovation (von Hippel, 2005) and for fostering design and innovation activities that are free of commercial demands and constraints (von Hippel, 2016). The notion of democracy here referred to having the opportunity to design and innovate and self-express as a citizen right (Torrance & von Hippel, 2016), and user communities were seen as settings that could offer the material and social means for such citizen activities (von Hippel, 2016).

In this view, hosted user communities are a win–win equation. Hosted communities give power for design savvy people to innovate and gain influence over host products and services, enjoy the fun of design activities, and access the design resources and social community which may not come into being without the ‘host’ (von Hippel, 2005, 2016). The host organization, in turn, gains solutions and user-domain understanding from the pool of users who are capable of innovating (Marchi, Giachetti, & De Gennaro, 2011; von Hippel, 2016). Such hosted communities were observed in ‘hybrid’ open source development (Shah, 2006; Sharma, Sugumaran, & Rajagopalan, 2002) and in various brand communities (Antorini, Muñiz Jr, & Askildsen, 2012; Marchi et al., 2011; Sawhney, Verona, & Prandelli, 2005).

PD has long endorsed and been part of technology-oriented social movements, hacker communities and open source software communities. Actual designing with and for user-designer communities has emerged largely in the current millennium. A consistent line of engagement with user-designer communities lies in the intersection of end-user development (EUD) and PD, focusing on the tools, infrastructures and social forms that user communities need in order to build their own means of production (Fischer, 2009; Lieberman, Paternò, Klann, & Wulf, 2006; Pipek & Wulf, 2009). EUD-PD has sought to capacitate communities and not just examine them as self-capacitated units, bringing its orientation closer to work on hosted communities in the user-innovation field. Other important lines of community-based PD (DiSalvo, Clement, Pipek, Simonsen, & Robertson, 2012) have been PD for cultural production and capacitating or empowering citizen groups regarding design (Björgvinsson, Ehn, & Hillgren, 2012; Bødker et al., 2016; Hillgren, Seravalli, & Emilson, 2011; Karasti & Syrjänen, 2004; Yang & Sung, 2016; Del Gaudio, Franzato, & Oliveira, 2016); infrastructuring for and with existing communities and fostering design ability within them (Botero & Hyysalo, 2013; Botero & Saad-Sulonen, 2010; Kim & Lee, 2014; Karasti & Baker, 2004, 2008); involving citizens in planning through digital platforms (Botero & Saad-Sulonen, 2010; Saad-Sulonen & Botero, 2008; Wallin, Horelli, & Saad-Sulonen, 2010); and nurturing infrastructure and information culture in local communities (Björgvinsson, Ehn, & Hillgren, 2012; DiSalvo, Clement, et al., 2012; Pawar & Redström, 2015).

Beyond the simple availability of tools and the means produced in collaboration, a longstanding ideal in many community-based PD initiatives has been to empower the community participants regarding design discourse and design capabilities (Bansler, 1989; Botero, 2013). Principles from political theory—such as class struggle, agonistic participation and thinking, and the creation of publics—have been explored and their implications for design democracy have been elaborated (Bansler, 1989; Björgvinsson et al., 2012; DiSalvo, Louw, Holstius, Nourbakhsh, & Akin, 2012; Ehn, 2008; Healey, 1997).

In this view, hosted user-designer communities hold the potential to be thoroughgoing forms of citizen engagement in public service development. The community can boost citizens’ collective abilities and thus also involve participants other than very design savvy enthusiasts, helping the participants to surpass their reliance on a benevolent host or academic designers concretizing their visions and needs into fully articulated service concepts and working solutions that can contest those constructed by civil servants or other patrons (Bovaird, 2007; Botero, 2013; Saad-Sulonen & Botero, 2008).

S&TS has a long tradition of examining citizen engagement with science and technology in-the-making. Its tradition is to study how technology, knowledge and expertise are (co)produced, not only as intellectual pursuits but as practical accomplishments wherein which social choices affect the outcomes (Williams & Edge, 1996; Williams, Slack, & Stewart, 2005). An important aspect of this interest has been how technological change could be rendered more democratically governed, and how citizens can directly affect design processes (Williams et al., 2005; Voß & Amelung, 2016). S&TS studies on hosted user communities show that they allow for a wide range of participant orientations and present a range of ways by which to affect design projects (Mozaffar, 2016; Johnson, Mozaffar, Campagnolo, Hyysalo, Pollock, & Williams, 2014; Pollock & Hyysalo, 2014). On the other hand, hosted user-designer communities can be organized as mere citizen panels and test beds whose remit is restricted to informing plans and solutions that are envisioned, realized and ultimately decided upon by the host institution developers (Williams et al., 2005).

In S&TS view, initiatives to democratize design through designer-user communities should not be approached normatively as sites to promote this or that democratic ideal or principle, but rather be examined as practical accomplishments regardless of the starting points, principles and outcomes taking place.

Keeping in mind their potential for very different outcomes, hosted user-designer communities are interesting for the examination of how collaborative design is realized in-practice (Jensen & Petersen, 2016; Verhaegh, van Oost, & Oudshoorn, 2016). The interest in understanding how collaborative design gets done is an emerging research area in the intersection between S&TS and design research. In design research, infrastructuring for PD (Bødker, Dindler, & Iversen, 2017) and research on software-user groups (Holmström & Henfridsson, 2006; Mozaffar, 2016; Tomes et al., 1996) suggests that the practical achievement of user-designer communities requires careful orchestration, adjustments, coalition building, liaisons and so on, which affect the form, processes and outcomes of the community and whatever design democracy arises. It is also affected by ‘intermediate designs’, in other words, the tools, templates, settings, rules and facilitation procedures that go into staging and formatting design in the community (Eriksen, 2012; Mattelmäki, Brandt, & Vaajakallio, 2011; Pirinen, 2016; Lee, Jaatinen, Salmi, Mattelmäki, Smeds, & Holopainen, 2018). In turn, S&TS research has examined the kinds of work that go into collaborative design as co-constitutive to the processes, ideals, methods, results and further uptake of outcomes; they are examined as internal issues of user involvement and not just external issues (e.g. organizational, context or excludable routine execution) (Elgaard Jensen, 2013; Jensen, 2012; Jensen & Petersen, 2016; Johnson, 2013; Oudshoorn, Rommes, & Stienstra, 2004; Verhaegh et al., 2016; Steen, 2011; Hyysalo & Hyysalo, 2018). For instance, Jensen and Petersen (2016) analysed how the project pragmatics and characteristic task series overrode and straddled the aims of user empowerment and fears of user exploitation in Danish user-driven innovation projects. Verhaegh et al. paid attention to the work that underlies community innovation once it is underway and how it gradually transforms community innovation into a citizen innovation community. This emerging research area has proceeded through careful case analyses to describe the collaborative design processes. The present study continues this line of investigation and we next examine the research set-up of the current study.

Methodology, Methods and Data

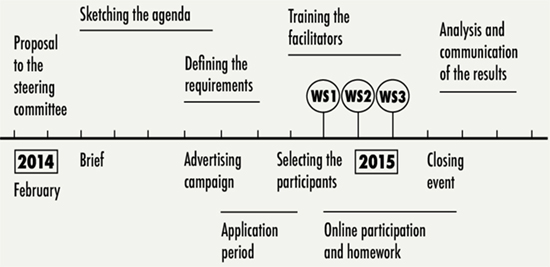

This study has been conducted through multiple-perspective and multiple-method research, carried out by a team of the three authors. The second author acted as the participation planner responsible for designing and organizing all of the CeLib collaborative design activities during 2012-2015 (from here on referred to as ‘participation planner’). Her participant observation of FCL was condensed in notes and synthesis documents, which were reviewed with other authors during the analysis stage. The first author acted as academic consultant to the CeLib participatory activities from 2012 to 2015 (from here on referred to as ‘consultant’). He was involved in the preplanning of the FCL community and in choosing the workshop format and methods used. To foster ownership of the events at the library, the consultant did not participate in any of the FCL workshops, but he was involved in reviewing the results and making adjustments to the process between the workshops. The third author acted in the role of a non-participant observer of FCL (from here on referred to as ‘observer’), covering eight planning meetings among the project workers, one training event for the facilitators, three workshops and the final event (see fig. 2 for the process outline). These events were documented in field notes and audio recordings. Numerous documents and emails produced during the planning process were collected.

The interim and final results of FCL were recorded, the latter as openly posted result descriptions on the CeLib website. To further improve the data set, the third author carried out interviews with the three key project team members and the consultant after the project. Formal feedback evaluation from and interviews with the participating library staff (n = 12) and participants of FCL (n = 28) were collected and analysed by the participation planner. Ten participants were also independently interviewed for a thesis in 2015 (Hyödynmaa, 2016), which the authors used for further data in their analysis. These modes of data gathering complemented each other and provided rich insider and outsider views of the project. All the data was thematically coded using open coding, and triangulated regarding data types and data gathering methods by the observer, then reviewed by the consultant and the participation planner, followed by an examination of the data in chronological sequence with respect to how different phases and aspects of the FCL process affected each other (Flick, 2014; Miles & Huberman, 1994). A presentational narrative was constructed by first and third authors and reiterated thrice with the second author.

The Context of FCL: CeLib and Citizen Participation

The Helsinki Central Library opened its doors at the heart of the city, opposite the Parliament House, on the 6th of December, 2018, after nearly two decades of planning and public consultation. It has been a considerable success with over a million visitors in just the first four months of operation—in a city of 650 000 residents—accompanied by massive media coverage both in the homeland and internationally (for example, a cover story in the NY Times and a feature in The Guardian). The opening marked a realization of an ambitious attempt by one of the most literate and digitally savvy nations in the world to reinvent the library for its population’s future needs.

Figure 1. An aerial overview of CeLib and key space reservations.

Image: ALA Architects and Helsinki City Library—reprinted with permission.

Finnish libraries are part of a global transformation where, instead of being just access points for books and other cultural productions, libraries offer alternative co-working spaces, serve as community centers, arrange activities and events with partners, provide means for new forms of cultural and digital production and act as hosts to democratic engagements and citizens’ initiatives (Dalsgaard, 2012; Hyysalo & Hyysalo, 2018). CeLib will spearhead this transformation. It is to serve as a sort of town square where social cohesion and democracy come to life. Each of its three floors is built to fulfill a different civic purpose. Its expansive ground floor includes, for instance, a restaurant, movie theater and several areas suited for activities and events and is meant for happenings, mingling, and discovery. The second floor is for noisy creative activity featuring creative space, music studios, game and visual studios, digital learning areas, various digital equipment and co-working spaces. The top floor features a brightly lit “book heaven” and playful children and family area for more conventional space for reading stories, relaxing and concentrating. The design is also transformable to accommodate new functions as the users’ needs are likely to change in the future.

CeLib preplanning preparations started around the turn of the millennium, and its preplanning specification was out in 2012, and the formal building decision was made by the city council in 2015. Helsinki library services have been in charge of the content and space allocations, the city planning office was in charge of the allotment and building specifics, and ALA Architects were in charge of the architectural design.

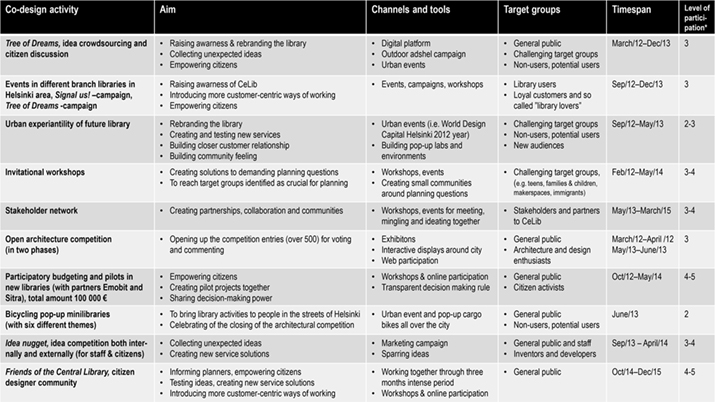

CeLib is also among the internationally rare large public projects that have featured active collaborative design activities throughout the planning process (Dalsgaard, 2012). Citizen participation has grown increasingly important in Helsinki City strategy to create more active residency (Boyer, Cook, & Steinberg, 2011; City of Helsinki, 2013, 2017). CeLib advanced citizen engagement in design considerably, having ten major initiatives (with various sub-activities) in its preplanning, 2012-2015, targeted at different groups of citizens (Figure 2). These activities used different channels to reach citizens and had a range of complementary aims and levels of participation. Consequently, they produced different outcomes and materials to support the planning process, ranging from gaining 2600 ‘library dreams’ from the public to in-depth elaboration of future library maker spaces (Hyysalo, Kohtala, Helminen, Mäkinen, Miettinen, & Muurinen, 2014; Hyysalo & Hyysalo, 2018). Some of the initiatives have been trailblazing, such as opening of all architectural competition entries to the public and significant volume participatory budgeting, which were both first-of-kind in Finland and have since been actively used in the country. FCL was the culmination of these preplanning stage activities as an attempt to initiate a long-standing and multifaceted citizen-designer group instead of running yet another project.

Figure 2. Collaborative design activities in CeLib preplanning stage.

*Level of participation defines the public’s role in participation processes. The 1-5 scale used is based on the IAP2 Spectrum for Public Participation by International Association of Participation https://www.iap2.org/page/pillars.

The Work of Constructing the FCL Citizen-Designer Community

Framing Work: Incorporating Different Views on Design Democracy

A volunteer citizen community to help public sector organizations was ideated by the consultant for Health Care context in 2012, but taken up in CeLib by the participation planner, who worked the idea further into a proposal for the FCL steering group for further FCL participation activities. Five aims were proposed for FCL: 1) testing existing ideas and preliminary service concepts; 2) resolving specific design questions; 3) gaining new and unexpected service concept ideas; 4) bringing library staff and the citizens closer together and introducing more customer-centred ways of working; 5) utilizing the results and processes in the development of the whole library network of Helsinki over the long haul.

These aims for the designer-user community incorporated three equally well-justified views held by the key actors in this early stage of FCL about what the democratic design engagement ought to be:

- Focused design participation by citizens in public service development projects was seen as a way to create a win–win situation, akin to the view by user innovation literature on innovation democracy in hosted communities (stressed originally by the consultant).

- Empowering citizens to influence and actively engage in design and dialogic relations in the planning of a major public undertaking, as well as in implementing the city strategy, in a manner akin to the ideals of democratic design participation in PD (emphasized by participation planner).

- Design participation as a means of raising awareness of CeLib among citizens and the city council members, i.e. bringing public design projects more firmly within the institutions of representative democracy, underscoring the ideals of equal participation opportunities in city strategy (underlined by the steering group and participation planner).

The proposal was approved, and a further definition of four focus areas for CeLib content ensued:

- A place for exploration and know-how: peer learning, gaming, citizenship skills.

- A library for communities: volunteering, families, children, rules for communal-space use.

- Books, games, movies, music: e-content in space, how to find content in the central library, how to share experiences and recommendations.

- A library for all citizens: multiculturalism, immigrants, tourists.

In May 2014, a team of three planners was formed to prepare FCL, and they began to put the aims and themes into a timeframe. Given the time needed to recruit participants, the workshop events could start in late October. About a month would be needed between the events to refine the results and to prepare for the next event. This practical calculation suggested three workshops and a closing event, with digital tasks in between. It was further evident that the events should mix gaining new ideas and concepts, testing existing concepts and solving issues that the CeLib planners and architects were challenged with. Figure 3 summarizes the timeline of the initiation pilot as it was eventually realized.

Figure 3. The timeline of the FCL pilot.

Analytically, framing work is part of alignment work in community innovation (Verhaegh et al., 2016). It binds together considerations of design choices often discussed under the openness of brief, purpose, scope of design and scope of change sought (Lee et al., 2018). In a case of sustained community initiatives, framing work addresses not only the different instrumental interests of the involved actors but also the underlying ideals as to what such community ought to be about. The framing of FCL incorporated ambitious citizen empowerment and design community ideals with more traditional informing from civil servants and testing of their ideas. The appeal to the versatility of the community in catering for these different ideals of democratic design successfully kept these different views from colliding, yet it postponed the potential tensions to other forms of work in the set-up process.

Relevance Work: Ensuring Implementability within Large Planning Project

The second part of the alignment work in FCL concerned relevance. Whilst the steering group indicated the targets and theme areas for FCL, it did not indicate how, when and in what form the results from FCL would be utilized in CeLib planning or more widely. The different orientations towards the user-designer community added to the questions regarding what FCL was to accomplish. As the planning of both the CeLib premises and the content of its services as well as its various participatory activities had proceeded for some years, added value was expected on top of the existing 2,600 ideas gathered from citizens, previous pilots and so on that had already been pursued (Hyysalo & Hyysalo, 2014).

Anchoring results to overall planning proved challenging. The FCL team knew that the overall planning of the central library services—the concept, contents, operations, services—was behind schedule, as many definitive decisions were still open, and compatibility would not come automatically. The net result was that the team decided to focus the FCL’s activities on those aspects that appeared the most unclear and fuzzy in CeLib’s planning:

We started by thinking what is realistically possible to do in that amount of time, and what, from our perspective, are the biggest and most difficult challenges in the central library ... We have been working in this organization for a long time, so these understandings were quite shared. (Participation planner)

The consultant suggested defining at least the functional requirements for the envisioned services around the four content themes to ensure meaningful input for the work of the FCL community. The team translated the upper-level themes into more specified sub-questions that could be discussed with the citizens in the workshops; defined the design anchors; determined primary and secondary target groups, interest groups and internal stakeholder groups; constructed the functional requirements for what the services should do; and mapped out what user knowledge had already been gained as part of the previous CeLib collaborative design activities. Defining requirements in this manner for four large and ambiguous themes was demanding and entailed weeks of extra work in comparison to simply receiving the key requirements and open questions from the overall planning, as had been assumed at the beginning.

The definition effort did not settle the uncertainties either. As Dalsgaard and Eriksson (2013) note, large-scale participation projects are typically characterized by “long time spans, large or diverse groups of users, planning questions that are extensive in scope, complex project organisation and project management with various subgroups” (p. 399). The received wisdom of codesign and design management about early design engagement (Sanders & Stappers, 2008) does not quite hold in such contexts. There are parallel design avenues and gradual opening and closing-off of design spaces, many ‘early stages’ if you may (Botero, 2013; Murto, 2017). Citizen solutions to a yet-to-open design space could simply become solutions to an envisioned but never actually opened design space. Thus, for the FCL planners, a nagging concern remained that moving ahead with overall planning potentially increased, not lessened, ambiguity over relevance and implementation as it created a parallel—not derivative—needs specification, and their many attempts to clarify the needs from overall planning were not met:

The biggest challenge in this project has been that the assignment did not state clearly how the results will be utilized. (Project team member)

In hindsight, another team member conjectured that a lighter, even if more imprecise, method for needs specification would have sufficed just as well, given the uncertainties over relevance that remained.

Analytically, relevance work in a hosted community forms a crucial part of alignment work (Verhaegh et al., 2016), which lays ground for the community’s ability to deliver useful things towards the host and retaining the community meaningfulness for volunteers. FCL planning shows that the relevance can be arduous and difficult to build, in effect requiring tight coordination between overall planning and the planning of participatory efforts to ensure impactful citizen participation.

Selection Work: Citizen Representatives or Able Designers or Empowered Participants

The first collisions between democratic ideals emerged in selecting participants. FCL was publicly launched through a ‘job application’ campaign in the media, one and a half months before the first workshop. The campaign received 13,000 visits to the website by 6,700 different people, resulting in 95 two-page applications to the FCL community. Applications featured good diversity, with slight bias to higher education, middle age and women. Unsurprisingly, there were fewer applications from young people and citizens with an immigrant background—the two most difficult-to-reach customer segments for the city library. But it was a very good yield, nonetheless.

Figure 4. One of the campaign images for FCL portraying the collaborative design work.

Image: Helsinki City Library—reprinted with permission.

The application procedure gauged the applicants’ motivation, imagination, innovativeness, collaboration skills, demographic background (age, where they live in the city etc.) and which of the four content themes they were particularly interested in. The decision to divide the participants into four groups from the onset effectively meant that each of the three workshops would consist of four groups tackling different issues.

But who should be chosen? The question was at once a principled one, regarding what idea of democratic participation in design was followed in community composition, and also a constrained one by simple practical issues. In terms of democratic principles, the library being a tax funded public institution is for everyone equally, and representing all members of society through the participating citizens was clearly a key value in selection. However, the hackathon type of workshops might only work out with citizens who had considerable domain expertise and design skill. A mix of representativeness and ability sounded good for community dynamics, yet practically difficult. Having four themes in each workshop meant that at least eight library staff members were needed as facilitators and notetakers to run the workshops. This number could not be increased much, and if the workshops were to empower participants with less design background, seven participants in each thematic group appeared as the manageable maximum. While the ‘job applications’ gave rich information on participants to ground the selection decisions, with 28 selected applicants featuring a mix of design ability and representativeness, each thematic group would consist of a relatively low number of design savvy people and limited representativeness of the general population.

Analytically, mixing of ideals of design democracy in small group composition was the first moment where the different views of design democracy could no longer be kept separate and had to be worked out and ‘traded-off’. The practical limitations of staffing the workshop events prevented circumventing the tension between representativeness and ability by the simple addition of more participants, and the mundane project pragmatics started to become just as consequential to the form of FCL than the underlying principles that guided its set-up process.

Constituency Building Work: Finding and Training Staff Facilitators

To foster ownership of the process, of the hosted community, and of results within the library organization beyond the small team and steering group, the project team had decided to run FCL with internal staff only—a strategy compatible with ideals for how to increase design readiness in the organization (Dumas & Minzberg, 1989). They first contacted co-workers who were known to have facilitation experience and thematic understanding, but few could join as the events were held in the evenings and also required taking time off busy daily tasks. The project team extended the invitation wider, now cautious of the time commitment FCL would require, and got a better response. The downside was that these facilitators were less experienced and were promised to only receive a light package of background information on the objectives and methods and needing to attend only one training meeting. This allowed the project team to show how the templates such as customer journey maps were to be filled in and discuss what was facilitators should do, but there was no time to let the facilitators try the procedures on their own.

Analytically, the aim to build design competency in the organization and the resulting decision to run FCL with internal library staff added further constraints to FCL process. It affected the subsequent simplification to the methods, templates and timings, and as we discuss next, added to the preparatory tasks needed to run the process as well as post-workshop results refinement process.

Intermediate Design Work: Workshops, Methods, Templates and Timing

Authors had previously organized tens of codesign workshops. However, as FCL preparations progressed, they came to realize that a series of cumulative user-designer workshops presented a considerably more demanding format to prepare and run than any individual workshop would be. Because of the cumulative progression, each step in the process more or less had to succeed in all sub-groups, or else the next step could collapse. The use of four content themes meant in many respects organizing twelve different mini-workshops instead of three events. At the same time the progression could not be tightly scripted; seeking to foster participant ownership of goals, solutions, and design process meant that the preparations had to incorporate a considerable amount of built-in openness. A further set of considerations concerned the staff facilitators and notetakers on whom the community events relied, and who should not be pushed beyond their limits in running the workshops.

The participation planner and consultant created several designs for the workshop series over the months leading to FCL’s launch, covering interim goals for each three-hour workshop; arrangements to help participants interact with each other and for fostering ownership and (high) quality of deliberation among the participants; how to inform the participants about the CeLib planning without suppressing their independent views; methods and templates to be used in each phase; estimations and measures for managing fatigue and atmosphere in different stages of each workshop and the series; how facilitators could handle participants different orientations and styles of working; and the eventual scheduling and phasing of the each workshop and the overall series in such a way that these considerations would be sensibly included and trade-offs would not prove untenable regarding any one aspect.

After the facilitator training in October, 2014, workshop outlines included estimated progression, means, and facilitator roles described down to a five-minute precision, associated with contingency measures and guidance on how to facilitate and record the discussions and solutions.

In this scheme the first workshop was to ideate library services in pairs, akin to speed dating, followed by an idea generation exercise done individually, and finally sharing the ideas with others in groups. The variation between individual, pair and group work was to catalyze interactions and to allow participants to express development ideas they may already have had before coming to the workshop. The second workshop was to move towards concretizing selected ideas into service concepts. This workshop was aimed at using customer journey and service blueprint templates to aid the participants in creating two to three articulated concepts in each group. The third workshop was planned to tie up any remaining loose ends and then focus on testing ideas which the CeLib project and architects had and which needed user insight to resolve. Time for participants’ mutual discussions was built both within and after workshop hours through extended space reservation times. For the interim times between the workshops, digital participation tasks were planned.

Analytically, the workshop design process proved complex and challenging, because the outcomes needed to cumulate. The workshops were tightly paced and featured high uncertainty over how the participants in each subgroup would come to relate to each other, how quickly they would be able to work, and how much room should be given to open discussion versus the concretization of ideas, concepts and solutions proposals. Importantly, all the earlier decisions bore effect on the intermediate designs: the framing and goals, the action plan, subgroup composition and participant selection all in turn led to iterations and created a framing for these.

Collaboration Work: Workshop Facilitation, Results Archaeology and Refinement

The workshop series began in November, 2014 with a welcome meal during which FCL was inaugurated and CeLib planning was explained by the main architect. After playful mutual introductions, the participants moved to their small groups accompanied by a facilitator and a notetaker. The dialogues with the main architect and the participants lasted longer than expected, but this ‘positive disaster’ was mitigated by adjusting the scheduling, and the expedited workshop worked well. The ideas gathered from each group were many and of high quality and required only little polishing and clarification before being used to feed forward to the next workshop and to CeLib main planners. After the event there was an excited atmosphere among the participants and jubilation amongst the project team as FCL had started on the right foot.

Figure 5. Group ideation and discussion in one of the FCL subgroups. Image: Virve Hyysalo.

The first important insights also began to emerge. For instance, the planners and project team had considered tourists, immigrants and minority cultural groups as three distinct customer groups. FCL underscored, however, that the new downtown library would form an initial contact point to Finnish culture to many, and with respect to these cultural entry services, the needs of the three groups were convergent. Given that the participants in this FCL subgroup had, for example, worked in cultural services for immigrants and immigrated to Helsinki themselves this was a fundamental insight regarding what role and services the library could focus on. Similar insights also emerged regarding what the participants found or did not find interesting:

On many occasions the participants thought that our questions were not interesting or relevant. For example, we thought that it was important that the space be recognized as a library, whereas the participants did not consider this to be important at all. I guess it was beneficial for us to ponder why this is so important for us in the first place. (Interaction designer)

In the second workshop, which was held in December 2014, the participants got to continue to concretize their most prominent ideas into service concepts. Group dynamics and progression varied greatly between the four groups and influenced the group’s capability to create ideas and refine concepts more than expected. This variety required adjustments to the facilitation style, the timing of tasks and the techniques used. Further issues arose from knowledge and skill asymmetries as some participants were hactivists or leading experts in specific fields (e.g. open data) or community activists (e.g. in an established literary association and in a well-known youth squatters’ association), whereas others were just ordinary city residents. The solution to mix representative and design savvy people proved to be particularly tasking:

[In future digital services group] one older participant did not understand what gaming was, had never heard of maker culture and could not follow when the group discussed mobile technology. It slowed down the whole group significantly. (Project team member)

Subsequently, facilitators found it difficult to guide the discussions as they frequently drifted away from the task at hand. It was difficult to instruct some of the participants in the collaborative use of journey maps and blueprint templates, which lead to difficulties in documentation within the available timeframe:

[The participants] did not manage to elaborate the concepts very far during the workshop. An option would have been to manage and guide the work firmly, but then the work would have been dictated more by the [facilitator] rather than the users. (Library planner)

Whilst participants appeared satisfied with the workshop, the templates and notes collected from the groups appeared scant, unclear and incoherent. Had the workshop resulted in a failure? Participation planner decided to contact all the facilitators and notetakers to make sure whether there was missing text, context information, or service elements. There indeed was, and this ‘results archeology’ eventually lasted for several days. It gradually revealed several original concepts and content discussions that had just been ill-documented in the flurry of the workshop. The third workshop was subsequently redesigned to include a continuation from the second workshop where participants commented on the reconstructed concepts, and (to organizers’ great relief) asserted these being what they had intended with minor corrections. The workshop then moved to immediate open questions asked by architects and planners, which provided good insights and worked as planned.

Between these workshops, online participation was open to all citizens. Tasks for online participation were complementary to FCL workshop tasks, and chosen so that they were possible to demonstrate and visualize online. The tasks received 5–40 comments/ideas each, some of which were further expanded on in the workshops and integrated and published as part of the final results. The yield of online participation was a positive surprise, even though it did not result in the level of elaboration and exploration of concepts as the workshops did.

The workshop events were the time when ‘rubber met the road’ and all the earlier decisions became consequential. Whilst other parts of the process flowed smoothly, the design concept elaboration phase suffered from tensions built up in earlier phases stemming from relatively inexperienced facilitators and note takers supporting and documenting the rapid work of mixed groups in which many participants had not designed anything before. The demands were considerable, including finding balance between more upper-level discussion among groups regarding the ideas and working on detailed service concepts; finding a balance between creating team spirit and productive work; balancing open ideas and opinions with directly planning relevant topics’ foci in guided discussions; balancing more rigid methods with explorative ideation; balancing ‘pushing’ participants towards concept elaboration and remaining neutral in facilitation; and balancing emphasizing documentation with letting the group deliberate while talking, even when documentation lagged behind. Amongst these tensions, the collaboration work succeeded well, with the biggest challenge being the documentation which could eventually be compensated for by extra work by the project team.

The Outcomes of FCL

In February 2015, the pilot was wrapped up with a final event held in Helsinki City Hall, where participants presented their work to the vice-mayor, library management and architects. The FCL elaborated concepts in the following seven areas (resulting in around one hundred pages of documentation):

- Voluntary work in libraries: FCL clarified seven different types of citizen voluntary work in libraries and what the differences and benefits of these are for different people. These were elaborated in service blueprints and user personas for two different enrolments, introduction and operation models for voluntary work.

- Peer learning, peer connecting and skill match-making: FCL elaborated on requirement specifications for Helsinki libraries’ specific application ‘the Connector’.

- The service offering 21st century digital and citizen skills: FCL provided commentary and over twenty additional suggestions for this service offering concept.

- The service offering of CeLib regarding local democracy, democratic society and urban culture: FCL elaborated on 11 different event formats; nine concepts of democratic youth education; the concept of ‘Finland in decision’ for connecting CeLib to the current week’s decisions in Finnish parliament; elaborating what help CeLib could provide for navigating City of Helsinki bureaucracy; and meeting formats with local politicians and for arts policy.

- A service offering for immigrants and tourists: FCL clarified an entry point help concept for living in the City of Helsinki called ‘Start Here’ (with 11 different facets); a further ‘Guide to Helsinki’ concept for getting into the local culture (with 12 sub-concepts); peer activities and a networking concept; ideating what could be a bureaucratic guide point; and ideated joint event formats with partners such as Multicultural Helsinki.

- The redesign of digital platforms of Helsinki area libraries: FCL provided critical scrutiny of current digital platforms and services by library services, building a vision of what should be minimally achieved and ideating a ‘collider’ service to match unexpected ideas to library customers and a ‘shadow library’ concept of a moderated digital repository of peer-created art and productions done within CeLib.

- Finally, the CeLib manifest was a concept for a peer-created guide of conduct for the library of the 21st century and example statements regarding how to make it visible.

FCL further validated and gave comments on numerous CeLib planners’ ongoing design tasks, and it contributed critical insight that was divergent to planner assumptions about CeLib and its services. These contributions were publicly acknowledged as valuable.

The FCL participant feedback was very positive: 25/25 respondents recommended that FCL should be continued after the pilot, and 22/25 answered that they themselves would be willing to participate in the future. Open responses showed praise for the initiative:

For the first time I really identified myself as a Helsinki resident. I felt [FCL] was something very important. I also felt that my opinions and ideas were truly cared about. Our group worked well towards shared goals in a positive way. (Participant A)

Thanks for well-coordinated and well-planned sessions ... After the sessions the feeling was as if one had just run a marathon (I was always pretty exhausted from all the innovating). (Participant B)

When interviewed later for an independent thesis (Hyödynmaa, 2016), the participants regarded FCL as well organized, planned and facilitated, the atmosphere being positive and featuring high commitment by the citizens and library staff alike. The respondents particularly valued learning new things about the library services and participatory planning activities, as well as valuing interactions with fellow workshop participants.

The library staff facilitators expressed equally enthusiastic and positive views about the experience. They reported having learned new skills outside their routine competencies and came to view their work and the library organization from customer and citizen perspectives, and as a part of a changing society.

From my point of view, participatory design is definitely the direction in which we should be heading in the public sector. Citizens today expect more transparent, accessible and responsive services, and those expectations are rising ... Unlike how it is sometimes assumed, we do not wish to loiter, but wish to do interesting things in good teams. I gained a lot of joy from this, and it enriched my own work. (Facilitator, city library IT services)

Another facilitator noted:

Workshops are a brilliant way to make real-time contact and have a chance to directly hear from citizens how they experience our services. (Planner, city library)

Three things to improve were raised in the staff feedback: there should be more integral participation from the management and top-level planners from the onset; there should be clearer indication of how the results would be implemented in CeLib planning; and there should be deeper training in the participative methods that were used.

For the FCL project team the key results were less about what services were needed and more about the specifics of their design and the way of designing them, particularly the various new generation digital concepts for the new era of libraries. Regarding the continuation of the citizen-designer community, its nucleus was successfully set-up through the pilot, but the city council approval marked the end of the participatory concept planning of CeLib. Participation planner’s job description was broadened to bring co-design and citizen involvement to all Helsinki library development projects, and then further to all cultural and recreational services in the city. In these ensuing projects she involved FCL members and on-line participants. A continuation proposal regarding the citizen-designer community was approved in 2017, yet the delay in formal continuation meant that some networks and momentum had to be rebuilt. FCL further contributed to the expansion of citizen participation activities in the City of Helsinki in new projects and the yet wider ‘friends’ activities that commenced in 2018. With the nearly unanimous positive final city council vote on CeLib in 2015, FCL can be seen met its aims in informing representative democratic decision making.

Discussion

We have outlined the kinds of work that go into the designing and running of the beginnings of a user-designer community. FCL—as an ambitious, successful, and well-resourced initiative realized by a relatively expert team—presents a good case for such analysis. It renders weak the counter argument that the considerable amount of issues, tensions and work would have simply resulted from an inadequate understanding of collaborative design.

The first key finding answers our second research question on how different ideas and ideals of design come to affect citizen-designer communities. Contrary to most user innovation and participatory design literatures (e.g., von Hippel, 2005; Robertson & Simonsen, 2012) citizen design participation in large public projects can simultaneously be driven by a plurality of well justified even if partially conflicting positions on what democratizing design should be. Positions ranging from informing decision making by elected officials with citizen views, to empowering representative citizens in making design decisions and to providing opportunities for design savvy citizens to directly affect the design of large public projects all have their justifications and limits. Yet, particularly in large real-life projects, active framing work is needed to reconcile these. FCL case shows how the framing work may not need to result in a unified and shared view among key actors, but the remaining underlying tensions do affect later design phases, in a sense becoming postponed to be settled at a later time.

The postponement is possible because the citizen engagement in relatively long-term, and open endeavors such as founding citizen-designer communities are realized through a range of other types of work that not only ‘operationalize’ but permeate the original framing with their own possibilities, constraints and skillsets involved (Hyysalo & Hyysalo, 2018). The types of work visible in FCL reside between initial alignment work and the running and expanding of the community, which have been documented previously by Verhaegh et al. (2016). Selection work concretizes the grounds by which participating citizens are chosen. FCL selection work highlights how selecting is not just choosing people. If it was just for balancing representativeness and ability, then simply adding in more people with desired characteristics would have been an easy solution. However, as the aim was also to empower the participants in close collaborative workshops, this set limits on the number of people that could be involved. Selection to FCL was further constrained by the ambitious internal competence building work, which further limited the number of participants that could be handled in the set-up phase of FCL. The eventual mixed selection in small groups complicated the concept design work in the workshops, but it could still be balanced successfully by intermediate design work and collaboration work.

Thirdly, in large projects relevance work should not be belittled. There is no one ‘early stage’ in which citizen involvement could be targeted, but a series of gradually opening and closing design spaces for different spatial, service and digital concepts (Botero, 2013; Murto, 2017). In the FCL case, the relevance work landed largely on the shoulders of the project team, took extra time and increased ambiguities and uncertainties over the foci for which FCL’s efforts should be targeted and types of results that were to be attained. Ironically, design competence building in library services had not as yet reached the steering group and head planners to an extent that they would have recognized, amidst their other pressing commitments, the need to engage more interactively with specifying what types of results were most useful from the community.

Fourthly and finally, design work, both intermediate designing for the collaboration to happen and collaborative designing with citizens, holds considerable capacity in accommodating other permeating conditions. FCL workshop arrangements effectively balanced an array of tensions and constraints, which bore effect on them. Design cannot do miracles, however, and in the FCL case designing documentation and facilitation hung precariously close to collapsing—resulting from simply giving note takers and facilitators too many roles against the attainable training with the complexity of handling four parallel mixed groups with unified pacing of work. This analysis of the types of the requisite work and their relation to designing forms the answer to our first research question on what is the work involved in setting up citizen-designer communities.

Conclusions

We have argued that setting up a citizen-designer community requires several types of work that all include their own practical skillsets and considerations and are not just mere operationalizations of project aims or participatory principles. Research has had a tendency to report design related work insofar as it includes innovative aspects or new techniques or methods (Woolrych, Hornbaek, Frøkjaer, & Cockton, 2011). Research on participatory infrastructuring (Bødker et al., 2017) and on intermediate designing, as well as S&TS work on the realization of collaborative design have recently started to examine this more broadly (Jensen, 2012; Johnson, 2013; Jensen & Petersen, 2016; Verhaegh et al., 2016). In projects outside academia, such ‘pragmatics’ hold decisive influence on how the ideals, processes and outcomes of citizen participation are played out. Indeed, they influence what kind of design democracy can become fostered. This article has examined designer and organizer perspectives to these projects, and further research could examine why and how citizens organize their participation and non-participation in public service co-design, akin to studies that have examined this in company hosted contexts (Freeman, 2011; Johnson et al., 2014; Pollock & Hyysalo, 2014).

Finally, it is worth underscoring the interrelationship between this type of collaborative design work, resourcing to carry them out, and the type of democratic design engagements that become possible. A low budget, low facilitation, highly independent and community self-organization set-up may work with (elite) design-savvy activists, particularly in citizen-initiated and citizen-organized user-designer communities. But such an approach is unlikely to work if ordinary citizens are to do actual design beyond ideation and testing. FCL demonstrates that a hosted citizen-designer community can be made to work with diverse participants and a widely democratic participation frame and still achieve serious design concepts. This requires work and some resources but, in return, provides both principled and instrumental usefulness for both the host and the participants. Tackling real, ongoing design issues helps the host to avoid the common ‘ticking the participation box’ and ‘hoping they come and then magic happens’ orientations and gives citizens a strong sense of actually making a difference with their participation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from Academy of Finland project grant number 289520 “Getting Collaborative Design Done”, and INUSE research group members for their valuable comments to the early versions of the article as well as the three anonymous reviewers of IJDesign for their insightful comments.

References

- Antorini, Y. M. (2007). Brand community innovation. Køpenhamn, Denmark: Samfundslitteratur.

- Antorini, Y. M., Muñiz Jr, A. M., & Askildsen, T. (2012). Collaborating with customer communities: Lessons from the LEGO Group. MIT Sloan Management Review, 53(3), 73-79.

- Bansler, J. (1989). Systems development in Scandinavia. Three theoretical schools. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 1(1), 3-20.

- Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks: How social production transforms markets and freedom. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Bilandzic, M., & Foth, M. (2013). Libraries as coworking spaces: Understanding user motivations and perceived barriers to social learning. Library Hi Tech, 31(2), 254-273. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378831311329040

- Björgvinsson, E., Ehn, P., & Hillgren, P. -A. (2012). Agonistic participatory design: Working with marginalised social movements. CoDesign, 8(2-3), 127-144. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2012.672577

- Bødker, S., Dindler, C., & Iversen, O. S. (2017). Tying knots: Participatory infrastructuring at work. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 26(1-2), 245-273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-017-9268-y

- Bødker, S., Korsgaard, H., Lyle, P., & Saad-Sulonen, J. (2016). Happenstance, strategies and tactics: Intrinsic design in a volunteer-based community. In Proceedings of the 9th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 10:1–10:10). New York, NY: ACM. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2971485.2971564

- Botero, A. (2013). Expanding design space(s): Design in communal endeavours (Doctoral dissertation). Aalto School of Art, Design and Architecture, Aalto University, Helsinki, Finland. Retrieved from https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi:443/handle/123456789/11261

- Botero, A. & Hyysalo, S (2013). Ageing together: Steps towards evolutionary co-design in everyday practices. CoDesign, 9(1), 37-54.

- Botero, A., & Saad-Sulonen, J. (2008). Enhancing citizenship: The role of in-between infrastructures. In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Conference on Participatory Design (pp. 81-90). Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org.libproxy.aalto.fi/citation.cfm?id=1900453

- Bovaird, T. (2007). Beyond engagement and participation: User and community coproduction of public services. Public Administration Review, 67(5), 846-860.

- Boyer, B., Cook, J. W., & Steinberg, M. (2011). In studio: Recipes for systemic change. Helsinki Finland: Sitra.

- Dalsgaard, P. (2012). Participatory design in large-scale public projects: Challenges and opportunities. Design Issues, 28(3), 34-47.

- Dalsgaard, P., & Eriksson, E. (2013). Large-scale participation: a case study of a participatory approach to developing a new public library. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 399–408. ACM.

- Del Gaudio, C., Franzato, C., & Oliveira, A. (2016). Sharing design agency with local partners in participatory design. International Journal of Design, 10(1), 53-64.

- DiSalvo, C., Clement, A., Pipek, V., Simonsen, J., & Robertson, T. (2012). Participatory design for, with, and by communities. In S. Jesper & T. Robertson (Eds), (pp. 182-209). New York, NY: Routledge.

- DiSalvo, C., Louw, M., Holstius, D., Nourbakhsh, I., & Akin, A. (2012). Toward a public rhetoric through participatory design: Critical engagements and creative expression in the neighborhood networks project. Design Issues, 28(3), 48-61.

- Dumas, A., & Minzberg, H. (1989) Managing design designing management. In Design Management Journal, 1(1), 37-43.

- Ehn, P. (2008). Participation in design things. In Proceedings of the 10th Conference on Participatory Design (pp. 92-101). New York, NY: ACM.

- Elgaard Jensen, T. (2013). Doing techno anthropology: On sisters, customers and creative users in a medical device firm. In T. Børsen & L. Botin (Eds.), What is techno-anthropology? (pp. 331-364). Aalborg, Denmark: Aalborg University Press.

- Eriksen, M. A. (2012). Material matters in co-designing: Formatting & staging with participating materials in co-design projects, events & situations (Doctoral dissertation). Faculty of Culture and Society, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden.

- Fischer, G. (2009). End-user development and meta-design: Foundations for cultures of participation. In H. Lieberman, P. Fabio, & V. Wulf (Eds.), End-user development (pp. 3-14). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

- Flick, U. (2014). An introduction to qualitative research. London, UK: Sage.

- Freeman, S. (2011). Constructing a community: Myths and realities of the open development model (Doctoral dissertation). Helsinki, Finland: University of Helsinki Press.

- Healey, P. (1997). Collaborative planning: Shaping places in fragmented societies. Basingstoke, UK: Hampshire Macmillan.

- Helsingin kaupunki. (2013). Helsingin kaupungin strategiaohjelma 2013-2016 [The strategy programme of the City of Helsinki 2013-2016]. Helsinki, Finland: Helsingin kaupunki.

- Helsingin kaupunki. (2017). Maailman toimivin kaupunki—Helsingin kaupunkistrategia 2017–2021 [The most functioning city in the world—City strategy of Helsinki]. Helsinki, Finland: Helsingin kaupunki.

- Hienerth, C. (2006). The development of the rodeo kayaking industry. R&D Management, 36(3), 273-294.

- Hillgren, P. -A., Seravalli, A., & Emilson, A. (2011). Prototyping and infrastructuring in design for social innovation. CoDesign, 7(3-4), 169-183. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2011.630474

- Holmström, H. (2004). Community-based customer involvement for improving packaged software development. Gothenburg, Sweden: Göthenburg university.

- Holmström, H., & Henfridsson, O. (2006). Improving packaged software through online community knowledge. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 18(1), No. 2.

- Hyysalo, S. (2009). User innovation and everyday practices: Micro-innovation in sports industry development. R&D Management, 39(3), 247-258.

- Hyysalo, S., Elgaard Jenssen, T., & Oudshoorn, N. (Eds.). (2016). Introduction: The new production of users. In The new production of users: Changing innovation collectives and involvement strategies (pp. 1-44). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hyysalo, S., Juntunen, J., & Freeman, S. (2013). User innovation in sustainable home energy technologies. Energy Policy, 55, 490-500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.12.038

- Hyysalo, S., Johnson, M., & Juntunen, J. K. (2017). The diffusion of consumer innovation in sustainable energy technologies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 162, S70-S82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.045

- Hyysalo, S., Kohtala, C., Helminen, P., Mäkinen, S., Miettinen, V., & Muurinen, L. (2014). Collaborative futuring with and by makers. CoDesign, 10 (3-4), 209-228.

- Hyysalo, V., & Hyysalo, S. (2018). Mundane and strategic work in collaborative design. Design issues, 34(3), 42-58.

- Hyödynmaa, A. (2016). Demokratian leikkikentällä: Osallistava suunnittelu hallinnon ja demokratian murroksessa [In the playground of democracy: Participatory design in the transition of governance and democracy]. Retrieved from https://jyx.jyu.fi/dspace/handle/123456789/51927.

- Jensen, T. E. (2012). Intervention by invitation: New concerns and new versions of the user in STS. Science & Technology Studies, 25(1), 13-36. Retrieved from http://ojs.tsv.fi/index.php/sts/article/view/55279

- Jensen, T. E., & Petersen, M. K. (2016). Straddling, betting and passing: The configuration of user involvement in cross-sectorial innovation projects. In S. Hyysalo, T. E. Jensen, & N. Oudshoorn (Eds.), The new production of users (pp. 136-159). New York, NY: Routldge.

- Johnson, M. (2013). How social media changes user-centred design-cumulative and strategic user involvement with respect to developer–user social distance (Doctoral dissertation). Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Aalto University, Helsinki, Finland. Retrieved from https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/8842

- Johnson, M., Mozaffar, H., Campagnolo, G. M., Hyysalo, S., Pollock, N., & Williams, R. (2014). The managed prosumer: Evolving knowledge strategies in the design of information infrastructures. Information, Communication and Society, 17(7), 795-813.

- Karasti, H., & Baker, K. S. (2004). Infrastructuring for the long-term: Ecological information management. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on System Sciences. Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE Computer Society Press. DOI: 10.1109/HICSS.2004.1265077

- Karasti, H., & Baker, K. S. (2008). Community Design: Growing one’s own information infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 10th Conference on Participatory Design (pp. 217-220). New York, NY: ACM.

- Karasti, H., & Syrjänen, A. -L. (2004). Artful infrastructuring in two cases of community PD. In Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Participatory Design (pp. 20-30). New York, NY: ACM.

- Kim, H., & Lee, W. (2014). Everyday design as a design resource. International Journal of Design, 8(1), 1-13.

- Lee, J. -J., Jaatinen, M., Salmi, A., Mattelmäki, T., Smeds, R., & Holopainen, M. (2018). Design choices framework for co-creation projects. International Journal of Design, 12(2), 15-3.

- Lettl, C., Herstatt, C., & Gemunden, H. (2006). Users’ contributions to radical innovation: Evidence from four cases in the field of medical equipment technology. R&D Management, 36(3), 251-272.

- Lieberman, H., Paternò, F., Klann, M., & Wulf, V. (2006). End-user development: An emerging paradigm. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

- Luthje, C. (2004). Characteristics of innovating users in a consumer goods field: An empirical study of sport-related product consumers. Technovation, 24(9), 683-695.

- Luthje, C., Herstatt, C., & von Hippel, E. (2005). User innovators and “local” information: The case of mountain biking. Research Policy, 34(6), 951-965.

- Marchi, G., Giachetti, C., & De Gennaro, P. (2011). Extending lead-user theory to online brand communities: The case of the community Ducati. Technovation, 31(8), 350-361.

- Marquez, J. J., & Downey, A. (2016). Library service design: A LITA guide to holistic assessment, insight, and improvement. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Mattelmäki, T. (2006). Design probes. Helsinki, Finland: University of Art and Design Helsinki.

- Mattelmäki, T., Brandt, E., & Vaajakallio, K. (2011). On designing open-ended interpretations for collaborative design exploration. CoDesign, 7(2), 79-93.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mozaffar, H. (2016). User communities as multifunctional spaces: Innovation, colective voice, demand articulation, peer informing and professional identity (and more). In S. Hyysalo, T. E. Jensen, & N. Oudshoorn (Eds.), The new production of users (pp. 219-248). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Murto, P. (2017). Design integration in complex and networked product development: A case study of architectural design in the development process of a greener passenger ship. Helsinki, Finland: Aalto University.

- Oudshoorn, N., Rommes, E., & Stienstra, M. (2004). Configuring the user as everybody: Gender and design in information and communication technologies. Science, Technology & Human Values, 29(1), 30-63.

- Pawar, A., & Redström, J. (2015). Publics, participation and the making of the Umeå pantry. International Journal of Design, 10(1), 73-84.

- Pinch, T. (2016). Afterword: Users everywhere. In S. Hyysalo, T. E. Jensen, & N. Oudshoorn (Eds.), The new production of users: Changing innovation collectives and involvement strategies (pp. 325-334). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Pipek, V., & Wulf, V. (2009). Infrastructuring: Toward an integrated perspective on the design and use of information technology. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 10(5), 447-473.

- Pirinen, A. (2016). The barriers and enablers of co-design for services. International Journal of Design, 10(3), 27-42.

- Pollock, N., & Hyysalo, S. (2014). The business of being a user: The role of the reference actor in shaping packaged enterprise system acquisition and development. Mis Quarterly, 38(2), 473-496.

- Ratto, M. (2003). The pressure of opennes: The hybrid work of Linux free/open source kernel developers (Doctoral dissertation). Department of Communication, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA.

- Raymond, E. S. (1999). The cathedral & the bazaar. Beijing, China: O’Reilly.

- Raymond, E. S. (2001). The cathedral and the bazaar: Musings on Linux and open source by an accidental revolutionary. Cambridge, MA: O’Reilly.

- Riggs, W., & Von Hippel, E. (1994). Incentives to innovate and the sources of innovation: The case of scientific instruments. Research Policy, 23(4), 459-469.

- Robertson, T., & Simonsen, J. (2012). Participatory design: An introduction. In S. Jesper & T. Robertson (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of participatory design (pp. 1-18). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Saad-Sulonen, J., & Cabrera, A. B. (2008). Setting up a public participation project using the urban mediator tool: A case of collaboration between designers and city planners. In Proceedings of the 5th Nordic Conference on Human-computer Interaction (pp. 539-542). New York, NY: ACM.

- Sanders, E. B. -N., & Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. Co-Design, 4(1), 5-18.

- Sawhney, M., Verona, G., & Prandelli, E. (2005). Collaborating to create: The Internet as a platform for customer engagement in product innovation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19(4), 4-17.

- Shah, S. K. (2006). Motivation, governance, and the viability of hybrid forms in open source software development. Management Science, 52(7), 1000-1014.

- Shapiro, D. (2010). A modernised participatory design? A reply to Kyng. In Scandinavian Inf. Systems, 22(1), 69-76.

- Sharma, S., Sugumaran, V., & Rajagopalan, B. (2002). A framework for creating hybrid-open source software comunities. Information Systems Journal, 12(1), 7-25.

- Steen, M. (2011). Tensions in human-centred design. International Journal of CoDesign, 7(1), 45-60.

- Steen, M., Manschot, M., & De Koning, N. (2011). Benefits of co-design in service design projects. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 53-60.

- Tapscott, D., & Williams, A. D. (2008). Wikinomics: How mass collaboration changes everything. New York, NY: Portfolio.

- Thrift, N. (2006). Re-inventing invention: New tendencies in capitalist commodification. Economy and Society, 35(2), 279-306.

- Tomes, A., Armstrong, P., & Clark, M. (1996). User groups in action: The management of user inputs in the NPD process. Technovation, 16(10), 541-551.

- Torrance, A. W., & Von Hippel, E. (2016). Protecting the right to innovate: Our innovation wetlands. In S. Hyysalo, T. E. Jensen, & N. Oudshoorn (Eds.), The new production of users (pp. 45-74). New York, NY: Routldge.

- Vaajakallio, K., & Mattelmäki, T. (2014). Design games in codesign: As a tool, a mindset and a structure. CoDesign, 10(1), 63-77.

- Verhaegh, S., van Oost, E., & Oudshoorn, N. (2016). Innovation in civil society: The socio-material dynamics of community innovation. In S. Hyysalo, T. E. Jensen, & N. Oudshoorn (Eds.), The new production of users (pp. 193-218). New York, NY: Routledge.

- von Hippel, E. (2001). Innovation by user communities: Learning from open-source software. MIT Sloan Management Review, 42(4), 82-86.

- von Hippel, E. (2005). Democratizing innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- von Hippel, E. A. (2016). Free innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Voß s, J. -P., & Amelung, N. (2016). Innovating public participation methods: Technoscientization and reflexive engagement. Social Studies of Science, 46(5), 749-772.

- Wallin, S., Horelli, L., & Saad-Sulonen, J. (2010). Digital tools in participatory planning. Helsinki, Finland: Aalto University Press. Retrieved from https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/4832

- Williams, R., & Edge, D. (1996). The social shaping of technology. Research Policy, 25(6), 865-899.

- Williams, R., Slack, R., & Stewart, J. (2005). Social learning in technological innovation - Experimenting with information and communication technologies. Cheltenham, UK: Edgar Algar Publishing.

- Woolrych, A., Hornbaek, K., Frøkjaer, E., & Cockton, G. (2011). Ingredients and meals rather than recipes: A proposal for research that does not treat usability evaluation methods as indivisible wholes. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 27(10), 940-970.

- Yang, C. F., & Sung, T. J. (2016). Service design for social innovation through participatory action research. International Journal of Design, 10(1), 21-36.