Populating Architectural Design: Introducing Scenario-Based Design in Residential Care Projects

Valerie van der Linden 1,*, Hua Dong 2,3, and Ann Heylighen 1

1 KU Leuven, Dept. of Architecture, Research[x]Design, Leuven, Belgium

2 Loughborough University, Loughborough Design School, Loughborough, UK

3 College of Design and Innovation, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

Despite the very aim of designing living environments for people, the perspectives of the end users are underrepresented in architectural design processes. Architects are expected to address the challenges of a diverse and ageing society but, due to increasingly complex design processes, they often have limited access to the perspectives of those they are designing for. This study aims to bring people’s spatial experience to the foreground in architects’ design processes, by turning to techniques developed by related design disciplines. More precisely, it analyses the potential of scenario-based design, a family of techniques for exploring user experience in design, which architects are largely unfamiliar with. Based on elements like personas, scenarios, and user journeys, a scenario-based design approach tailored to architectural design’s particularities was developed. Test workshops were conducted in two architecture firms involved in designing residential care projects, and findings were discussed with an expert panel. Findings illustrate how these workshops offered architects insight into user profiles and themes, facilitated exploring and diversifying potential futures during design development, and supported communication with team members and the client. Additional opportunities and challenges are identified, which can advance the development of an integrated approach to support architects in designing human-centred environments.

Keywords – Architectural Practice, Design Techniques, Scenario-Based Design, User Experience.

Relevance to Design Practice – Leveraging the work on human-centred design developed in related design disciplines, we offer architects and their clients techniques to make user experience tangible, negotiable, and applicable in design. Designers from related disciplines can benefit from a reflection on the contributions, pitfalls, and broader application of scenario-based design.

Citation: van der Linden, V., Dong, H., & Heylighen, A. (2019). Populating architectural design: Introducing scenario-based design in residential care projects. International Journal of Design, 13(1), 21-36

Received January 18, 2018; Accepted March 25, 2019; Published April 30, 2019.

Copyright: © 2019 van der Linden, Dong, & Heylighen. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

*Corresponding Author: valerie.vanderlinden@kuleuven.be

Valerie van der Linden is a postdoctoral researcher in the Research[x]Design group at the KU Leuven Department of Architecture in Belgium. She collaborated on projects on inclusive design and care environments, and specifically investigates design-oriented ways to inform architects about people’s spatial experience. Valerie obtained a MSc and PhD in architectural engineering from KU Leuven and was a visiting PhD Fellow in the Human Centred Design group at the University of Twente (NL). She recently defended her PhD dissertation entitled Articulating user experience in architects’ knowing: Tailoring scenario-based design to architecture, which was supervised by prof. Ann Heylighen and prof. Hua Dong and funded by KU Leuven and the Research Foundation–Flanders (FWO). She particularly explores the potential of techniques from related design disciplines to support engagement with user experience in architectural briefing and design practices.

Hua Dong is Professor in Design at the Loughborough Design School. Her research career commenced at the Engineering Design Centre, University of Cambridge where she obtained her PhD and conducted postdoctoral research into inclusive design, collaborating with the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design at the Royal College of Art. She has taught industrial/product design at Brunel University and Tongji University. Hua successfully received grants from EPSRC, ESRC, AHRC, NESTA, and she has been awarded several prestigious fellowships in China. She has extensive experience of providing specialised design research consultancy to industries in the UK, Finland, and China, resulting in award-winning products. Hua has founded the Inclusive Design Research Group (in London and in Shanghai) and she was the Dean of the College of Arts and Media, Tongji University between 2014 and 2018. Hua is a council member of the Design Research Society and coordinates the InclusiveSIG.

Ann Heylighen studied architecture/engineering at the University of Leuven (KU Leuven), Belgium, and ETH Zürich, Switzerland, and conducted PhD and postdoctoral research at KU Leuven, Harvard University and UC Berkeley. Currently she is a research professor at the KU Leuven Department of Architecture and visiting professor at Sapienza Università di Roma, Italy. She teaches design theory, professional ethics and inclusive design and co-chairs Research[x]Design, a cross-disciplinary research group at the interface of design research and humanities/social sciences. She is interested in how space is experienced, how it is designed, and the relationship between both. She is associate editor of Design Studies, and was awarded several fellowships and grants, including two grants of the European Research Council (ERC) for her work on architectural design and disability.

Introduction

With its long tradition of designing people’s living environments, architectural design is known for its close relationship with people and even promoted as a vehicle for social projects (Gutman, 1972). Yet, however central to the discipline people may seem, the current position of users in the architectural design process is problematic (Imrie, 2003; Till, 2009): their perspectives are underrepresented and their experience remains a largely implicit dimension of design projects (Van der Linden, Dong, & Heylighen, 2018). Architectural design is being criticised for being depopulated (Imrie, 2003), hinting at the general absence not just of people in images, but also of explicit reference to use(rs) in design processes (Verhulst, Elsen, & Heylighen, 2016). As this implicitness hampers discussing user experience, our research seeks to develop design-oriented formats that manifest experiential aspects of architecture in design practice.

In design in general, the split between processes of design and practices of use (Redström, 2012) has introduced a gap between designers’ intent and users’ actual experience (Crilly, Maier, & Clarkson, 2008). In architectural design particularly, design processes have grown increasingly complex due to the various requirements architects need to take into account and the constellation of stakeholders involved. Especially in large-scale projects, the client typically does not coincide with the users, thus close collaboration with the client does not guarantee insight into use issues. Architects often have limited access to whom they are designing for and limited resources to invest in research. Several studies found that they, alternatively, use their own experience as a main reference (Cuff, 1989; Imrie, 2003; Verhulst et al., 2016). As a result, addressing the needs of future users can be particularly challenging for architects, especially when users’ experience differs substantially from their own.

Nevertheless, architects are expected to address user experience in several market segments. In healthcare, the shift towards patient- or person-centredness has prompted questions for architectural solutions that humanize care (Bromley, 2012). Yet, when designing, e.g., a residential care facility, it can be hard to imagine what home means for people with dementia (Van der Linden, Van Steenwinkel, Dong, & Heylighen, 2016). Having to juggle between stakeholders’ competing demands and conceptions of ageing and care further complicates the development of novel building concepts (Buse, Nettleton, Martin, & Twigg, 2017). This situation leaves architects with little means for advancing experiential aspects as intangible qualities of architecture and advocating them against other design aspects.

Architects typically take an expert mind-set of designing for users, rarely involving users directly (Oygür, 2018; Sanders, 2009; Van der Linden et al., 2018). In related disciplines like product, service, and interaction design, a different position of users has been engendered by movements like user-centred, human-centred, and empathic design. Here, understanding user experience has become a central topic and is even considered crucial for innovation (Koskinen, Mattelmäki, & Battarbee, 2003; Wright & McCarthy, 2010). In this context, hands-on techniques have been developed for designers to think holistically about people’s activities in order to design integrated solutions that support their interactions and improve the quality of their experience (Fulton Suri, 2003). These techniques seem to show considerable potential for involving future users’ perspectives during design but are largely unexplored in architecture. However, adopting them in architectural design would require careful tuning to its particularities, including the spatial character and big scale of what is designed, and the small scale of most architecture firms.

This study aims to analyse the potential for architecture of scenario-based design, a family of flexible techniques for explicitly and iteratively exploring user experience during design. Carroll’s (2000) often referred to framework for scenario-based design, as discussed below, was elaborated in the context of human-computer interaction, but draws as a theoretical basis on Schön’s (1983) work about reflective practice in, e.g., architecture. This hints at its relevance for architectural design too, as essentially scenario-based design addresses challenges that are inherent to design in general. A scenario can be considered a sketch of user experience, and as such relates to something architects already do: imagine future encounters with the building. Although architects usually imagine these encounters personally, without making them explicit (relying on their intuition, see also Oygür, 2018), the crafting of scenarios can also be externalised, so that they become food for discussion. Making people’s spatial experience tangible, negotiable, and applicable during design, scenario-based design is expected to support architects in designing human-centred environments.

Below, we outline the basic principles of scenario-based design and describe how we propose to tailor it to the particularities of architectural design. To this end, we rely on insights gained through an ethnographic study in several architecture firms, which allowed gaining in-depth insight into architects’ current ways of working and identifying challenges therein (Van der Linden, Dong, & Heylighen, in press), as well as through research and design work with master-level architecture students.1 Subsequently, we describe how the tailored scenario-based design approach was tested through workshops with two architecture firms involved in designing residential care environments, and how the applicability of the findings was assessed by an expert panel. The findings section articulates the contributions of the scenario-based design approach (in the areas of insight, design development, and communication) and identifies additional potential and challenges for implementation. The final sections interpret the findings and discuss our study’s limitations and opportunities for further integration of scenario-based design in architecture.

Scenario-Based Design

Basic Principles

Scenario-based design refers to a family of techniques to explore use situations explicitly and iteratively in the design process. Foregrounding user experience as a main design concern, the approach supports creative and reflective thinking by taking into account the diversity and dynamics of use situations and offers a frame of reference to evaluate design decisions (van der Bijl-Brouwer & van der Voort, 2013). Scenario-based design matured in human-computer interaction and software design (Carroll, 2000), fostering imagination of how people would interact with future technologies. It spread to other design disciplines but remained largely undiscovered in architectural design.2 Product (and service) designers embraced scenario-based design as a means to extend the understanding of user-product interaction beyond performance-related ergonomics, and integrate experiential aspects into the design of consumer products that would, for example, match people’s lifestyle (Fulton Suri & Marsh, 2000). Sketching future use early on in the design process makes real the quality of people’s experience in interaction with a design before substantial resources are committed to its development (Fulton Suri & Marsh, 2000). This kind of early test, done before prototyping and user testing, makes checking the design from users’ perspective integrated into instead of detached from the design process (Anggreeni, 2010).

A scenario is basically a story about people and their activities. Whether extensive or concise, this story contains some basic narrative elements (van der Bijl-Brouwer & van der Voort, 2013):

- The starting state consists of an actor with certain characteristics, who finds him/herself in a certain setting (possibly including other persons, objects and tools) and has a certain goal towards a design product–in the case of architecture: a building or space.

- The plot unfolds when the actor undertakes actions or is triggered by external events, initiating an interaction with the design product.

- This interaction engenders a positive or negative experience, which can offer input for the design if use issues are identified.

Scenarios can describe both typical or extreme situations and end positively or negatively in relation to the user’s goal (Bødker, 2000). Different types of scenarios can be distinguished, as their focus and level of detail can change with the design stage (Anggreeni, 2010). Current use scenarios (a.k.a. actual practice or problem scenarios) describe people’s current interactions. Shifting to the future domain, descriptions can range from explorative ideal use scenarios, over more elaborated future use scenarios to detailed interaction scenarios. Being easily recuperated and developed, scenarios are use-oriented design representations that serve the continuum of the design process:

It is widely agreed that the strength of the scenario is its ability to make design ideas concrete, that it helps maintain focus on the specific context, use, and user, and that it provides the opportunity to relate to both current and future conditions and issues. (Nielsen, 2013, p. 102)

Potential pitfalls of scenarios include presenting an uncritical rosy story, a stereotypical character or a one-sided perspective, lacking focus or confirming weak ideas (Fulton Suri & Marsh, 2000). Especially when used as an isolated technique, scenarios are criticised for not being anchored in reality and henceforth misused, as possibly a justification of particular features or presumed functionalities (Grudin & Pruitt, 2002). The character as driver for the plot can help to surpass merely looking at the sequence of actions, and to consider instead how this character feels about and makes sense of the situation (Nielsen, 2002). Scenarios can work with characters that are not particularly fleshed out, yet a more detailed description might enhance engagement (Grudin & Pruitt, 2002).

For this reason, scenarios are often used in conjuncture with personas, a technique to create vivid user profiles that was introduced by Cooper (2004) in human-computer interaction in the 1990s.3 These user profiles are usually founded on research (e.g., about target groups) but can also be based on or complemented by fiction (Blythe & Wright, 2006). The persona description includes elements like personality and motivations (Nielsen, 2002), in a way that allows designers “to extrapolate from partial knowledge of people to create coherent wholes and project them into new settings and situations” (Grudin & Pruitt, 2002, p. 149). Nielsen goes on and lists characteristics to be described that underpin motivations so as to create a believable rounded characters with inner conflicts and dynamics. Just like scenarios make use explicit, personas make assumptions about the users explicit, thus supporting reflection on the design and confrontation with reality: “one could populate an entire persona set with middle-aged white males, but it would be obvious that this is a mistake” (Grudin & Pruitt, 2002, p. 151).

Scenarios can be represented in many forms, ranging from textual to audio-visual, and even enacted through role-play (van der Bijl-Brouwer & van der Voort, 2013). As such they can be linked with techniques like storyboards and user journeys [a.k.a. customer (experience) journeys or customer journey maps], which outline a user’s interaction with a product or service. User journeys, for example, often entail a linear representation of this interaction, in which the different touchpoints with the product or service are investigated to improve user satisfaction (Følstad & Kvale, 2018).

As to the application spectrum of scenario-based design, scenarios “serve the double purpose of engendering the decisions made in the design situation, and of being a vehicle of communication between the participants, and even out of the group” (Bødker, 2000, p. 64). Their versatile nature grants scenarios various uses: from developing and exploring ideas (inspired by the everyday or critical nature of current use situations); to testing and evaluating ideas (where scenarios enable the comparison between different options); and illustrating a product (in terms of how the design will support daily activities and how decisions have been made); to even including stakeholders in the design process (where scenarios can improve communication; Nielsen, 2013). Scenario-based design does not need to exclude users but can provide guidance to user research and even user involvement while being closely tied to the design activity (Bødker, 2000).

Carroll (2000) elaborated a framework with five reasons for using scenario-based design in answer to design challenges which illustrates the particular mechanisms of scenario-based design. First, the emphasis on user activities that results from creating scenarios evokes reflection on the design from users’ perspectives when it is produced rather than afterwards. Also, in the typical instability of design situations and teams, this reflection starts from a stable basis, as scenarios are at the same time concrete (offering a specific interpretation and solution) and flexible (representing a tentative proposal that is easily revised or elaborated). In addition, as scenarios can be created from different perspectives, they enable designers to articulate the diverse and interdependent consequences of particular design moves. Moreover, patterns and themes in scenarios can be abstracted and exemplified, as such becoming incorporated in designers’ experience, which can be tapped in new situations. Finally, as representations of users’ activities, scenarios support a continuous focus on users’ needs and concerns as the essence of design, which is otherwise easily diverted to other constraints.

Tailoring to Architectural Design

We propose to select and tailor scenario-based design techniques based on architects’ particular ways of working. In this section we outline general recommendations by coupling observations of architects’ design practice (Van der Linden et al., in press) to the basic scenario-based design principles above. The Set-up section below describes the specific approach used in our study.

Our prior study suggests that scenarios may tie in with the natural way of designing of architects, who were observed uttering scenarios of potential building use, in an informal way (cf. Van der Linden et al., 2018). These scenarios, however, typically featured an abstract actor, often reflecting the architect him/herself, and showed little attention to user diversity. This predominantly one-sided (thus little confronting) perspective currently used in the scenarios limits their benefit. Combining scenarios with personas might improve the results by offering multiple perspectives that make the scenarios more engaging (Grudin & Pruitt, 2002). The narratives, moreover, reflect how user experience anecdotes (e.g., provided by the client) are currently passed on.

To be most relevant, these multiple perspectives need to be well-informed, yet architects report a lack of insight into other users’ experience (e.g., in older people, cf. Van der Linden et al., 2016). As neither involving the users’ perspective nor collecting information about them is common in architectural practice (cf. Sanders, 2009), architects are currently ill-equipped to draft personas themselves. Moreover, few architecture firms have in-house researchers who could take up this task. Supported by studies suggesting that research-based personas are most effective (Fulton Suri & Marsh, 2000; Miaskiewicz & Luxmoore, 2017), we propose to provide architects with rounded character (Nielsen, 2002) personas based on empirical research about how people experience the built environment. These can be drawn up by clients or researchers.

Another finding from studying architects’ current practice is that floor plans are the dominant design medium (Van der Linden et al., in press). Many informal scenarios considered by the architects observed concerned moving through a building and unfolding activities in space. To tie in with this representation method, we propose to introduce user journeys, which can be mapped onto the plans, as a way to make scenarios explicit. In addition to the architects’ observed focus on the building’s functionality and programme in floor plans, mapping user journeys onto floor plans could support assessing the design from the perspective of different user profiles.

The main adaptations of the scenario-based techniques for architectural design relate to scale: for product designers the built space sets the background against which user-product interaction unfolds, while for architects the space is the very object of design. While scenario-based design was initially applied to assess the effectiveness in a specific situation of, for example, a computer system targeting a particular consumer group, its adoption in product design shows its potential to address more diverse users and situations (Anggreeni, 2010). The complexity even increases in architectural design, as (public) space is typically interacted with over a longer time span and by a more diverse set of users. Therefore, it is important that personas and scenarios include broader information about people’s living environment, and that their interaction with it is considered in a larger area (e.g., the project site) and time frame (e.g., a typical day), even at near and distant futures. Given architecture’s more permanent nature, people’s interaction with the design should be assessed not so much in terms of user satisfaction, but with attention to the broader aspects affecting spatial experience (including perception, action and meaning, see below), and to potential conflicts between user groups or situations.

Methods

To test the tailored scenario-based design approach, we conducted workshops in the context of real-life projects in two architecture firms and discussed the findings with an expert panel. All professionals were active in Belgium. The choice for workshops was motivated not only by their suitability as a test format, but also by their flexibility to implement scenario-based design in architectural practice.

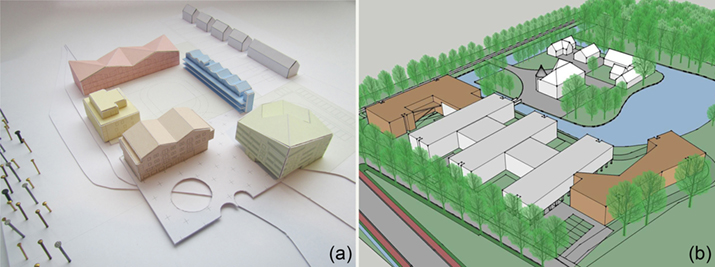

Both architecture firms participating in the test were seeking to anchor human-centredness in their design approach and were particularly interested in how residential care environments were experienced. One firm (ArchiSpectrum) had been involved in the previous stage of the research project, which investigated architects’ designerly ways of knowing about users (Van der Linden et al., in press), whereas the other firm (Plan-A) was new to the research project.4 Residential care (mainly for older people) represents an important segment of both firms’ portfolio and was considered a sector in transition, requiring more attention to residents’ experience, and calling for architects’ input in advancing care environments. The agreed aim of the workshops was to think about residential care environments from the perspective of diverse users, by means of an approach that is applicable in different projects and by several team members. The participating firms each selected a residential care project among their ongoing projects: ArchiSpectrum chose a new, innovative residential care campus with mainly service flats; Plan-A chose the rebuilding and extension of a ward in an existing, more traditional residential care facility. At the time of testing, both projects were in the conceptual design stage, which entailed site analysis, volumetric study, and feasibility study (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Selected residential care projects: (a) sketch model of ArchiSpectrum’s project (© ArchiSpectrum), (b) draft 3D model of Plan-A’s project (© Plan-A). Reprinted with permission.

In each architecture firm the test consisted of two three-hour workshops and a feedback session. The workshops included scenario-based design exercises (combining techniques like personas, scenarios, and user journeys), as described below (see Set-up). The feedback sessions offered participants an opportunity to reflect on both the potential and the limitations of the approach and suggest changes. The firms were asked to invite people with a variety of roles in the firm, both people who were closely involved with the selected project and people who were not. The participants included partners, architects, interior architects, and in the case of ArchiSpectrum also a communication manager. Both firms also arranged the presence of a client representative.

In order to gauge the broader applicability of the tailored approach for architectural practice in other types of projects and with other types of architecture firms and clients, the findings from the workshops were presented to an expert panel. The panel members included two architects,5 one interior architect and two professional clients, who had not been involved in the test workshops. The architects invited for the expert panel represented smaller architecture firms, in order to complement the perspective of the larger firms that participated in the workshops. The panel members described how user experience was currently addressed in their practice, commented on the findings from the workshops, and discussed the potential of adopting a scenario-based design approach in their practice, including points of attention to assure its viability.

Table 1 lists the participants in the different sessions. The first author prepared and led all sessions, but was assisted by varying colleagues, including the last author in the focus groups at ArchiSpectrum and the expert panel. All workshop materials were copied for analysis and observational notes were drawn up during and after the workshops (e.g., on the way participants took on the assignments, the information picked-up from the input, the content of discussions, the argumentation of design decisions, the contributions of individual participants, and comments on how participants experienced the exercises). The feedback sessions and expert panel meeting were audio recorded and summarised. Observations of how the techniques were adopted, the participants’ feedback, and the expert panel’s assessment were confronted and analysed qualitatively with input from different researchers in order to identify contributions, challenges and additional potential of the scenario-based design approach. The findings below are illustrated with quotes that were transcribed verbatim and translated by the authors.

Table 1. Participants in the scenario-based design workshops & expert panel.

| ArchiSpectrum | Plan-A | |

| Workshop 1 | 6 participants from the firm Client representative |

7 participants from the firm |

| Workshop 2 | 8 participants from the firm Client representative |

10 participants from the firm Client representative |

| Feedback Session | Focus groups: 3 & 4 participants from the firm Interview: client representative |

Focus group: 6 participants from the firm Interview: client representative |

| External architects and clients | ||

| Expert Panel | Focus group: architect, interior architect, 2 clients Interview: architect |

|

Set-up

Workshop 1

The aim of workshop 1 was to explore and become familiar with the perspectives of potential users of residential care environments. First, the researchers presented a short introduction to scenario-based design. Next, the participants were offered insight into the experience of residential care environments through personas and corresponding current use scenarios. The content was based on qualitative research conducted in the researchers’ group and had been selected in consultation with the firms.6 To initiate analysis, the researchers had highlighted themes relevant to design (e.g., appropriation, orientation, living with strangers).

Figure 2. Profile pictures of the personas featuring in the scenario-based design workshops on residential care environments.

Figure 2 gives an overview of the personas representing a selection of potential users of residential care environments.

- George (90) lives in a rural residential care facility but is still quite active. He feels homesick and is looking for meaningful activities.

- Agnes (86) dislikes her situation and co-residents in a residential care facility, where she has been moved to the dementia unit. She uses a wheelchair but cannot operate it herself.

- Martha (82) deliberately moved to a service flat in the town centre, as she has started to experience physical problems. She prides herself in being a good hostess and tries keeping her place neat and tidy.

- Jozef (77) volunteers in a day centre as a computer teacher. He lives in the countryside and needs to take over tasks from his wife who has Parkinson’s.

- Pierre (62) just retired and pays a daily visit to his mother with dementia living in an urban residential care facility. He is concerned with making his mother feel at home there.

- Nadine (52) was recently diagnosed with early-onset dementia. To help her cope with her changing situation, she and her husband made some modifications to their house in the suburbs.

- Zeyneb (31) works as a professional caregiver in a residential care facility. She is concerned with residents’ safety, personal contact, and work-life balance.

The participants browsed the information and added post-its with themes they found relevant to the design. Subsequently their insights were discussed in group to create a shared understanding. Next, the designer in charge presented the project the firm had selected for the workshops, highlighting the ambitions and the site’s potential and limitations. In the final phase of the workshop, the participants started from the identified use issues and themes to brainstorm about ideal use scenarios for the personas–on the project site or in residential care generally.

Workshop 2

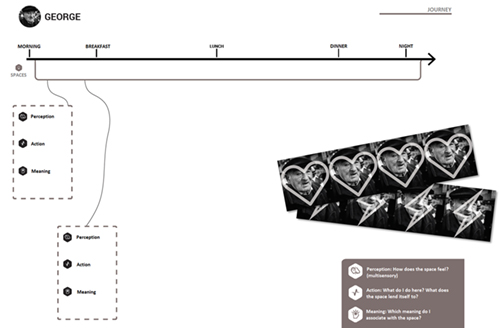

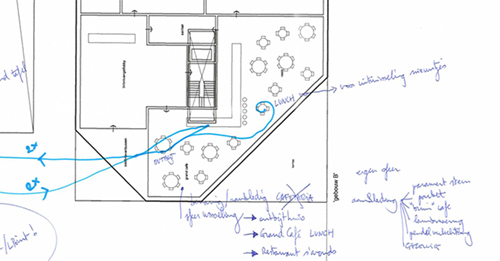

Workshop 2 aimed to examine the projects’ current plans from the personas’ perspectives. To explore their experiences, the workshop was set up around potential user activities and their unfolding in space and time.

In the first part of the workshop, the participants put themselves into each of the personas’ shoes and mapped a typical day in his/her life on the current project plans and on a corresponding timeline (which marked anchor moments like meals rather than clock time). Through unravelling for each space in the journey the aspects that constitute the persona’s experience (i.e., how they perceive the space in a multisensory way, what they do in there or what the space lends itself for, and what meaning they attribute to it), they assessed whether more attention was needed in the design. Figure 3 shows a journey template, including a timeline to map the spaces from the plans, a stack of cards to analyse the persona’s spatial experience (in terms of perception, action, and meaning), and sticker sheets to indicate the resulting assessment on the plans with a heart or lightning.

In the second part of this workshop, the personas’ perspectives were combined in order to formulate overall design recommendations for significant spaces in the project, as an outcome of the workshops.

Figure 3. User journey template used in the workshop, featuring a timeline, analysis cards, and assessment stickers (translated).

Findings

Based on our analysis of the workshops and expert panel meeting, there are three areas where the tailored scenario-based design approach can contribute to architects’ design process: insight into use issues, design development (making concrete and assessing solutions, based on user perspectives), and communication of experiential aspects. Participants saw additional potential beyond the scope of the test workshops and identified challenges to broader implication, which are discussed below.

Insight

The first contribution is becoming acquainted with user profiles and themes that are relevant to them. This became particularly apparent in workshop 1.

The personas allowed participants to become acquainted with a diversity of user profiles through vivid descriptions. The participants especially appreciated gaining insight into perspectives and contexts they were less familiar with or had difficulty to access, for example younger designers seeing the perspective of older people living in a residential care facility. Additionally, the unusual situation of a person of similar age attracted much attention, as was the case with the profile of Nadine, a woman with early-onset dementia. A recurring remark during the feedback and expert panel sessions was that, although it was considered one of architects’ main tasks, placing themselves in the position of others was often hard in their current practice. Personas forced them to leave their own point of view and take another one. There was a consensus that the less familiar the user, the harder to imagine oneself in the situation (and the harder to design appropriate spaces), thus the more relevant the personas. Because they were research-based, they were considered to be highly trustworthy.

The persona descriptions seemed successful in fostering participants’ engagement. The personas were immediately and repeatedly referred to by their names as if they were acquaintances. As an architect at Plan-A remarked, the characters engender a connection that a typical list of features does not. The elements to describe the persona’s character included personal details, family situation, personality, care profile, living environment, and attitude towards the future. For example, the participants got to know George as a 90-year-old widower in quite good health who is passionate about history and nature. Rooted in the local area, where he used to be a fruit grower, George feels homesick for his land since he moved to the local residential care facility. While enjoying the practical care, he misses social interaction and pursuits–yet it is not his nature to complain.

Apart from such character description, the persona sheets (Figure 4) featured current use scenarios, which were particularly appreciated because they offered insight into people’s motives and also their frustrations and obstacles. In the case of Agnes, the participants got to understand her silent frustration when, being positioned among the co-residents with dementia she dislikes and without a view of the television or a window, she spent her time waiting to be brought back to her room where she feels more in control. The pictures and plans supported a quick understanding of how the built environment affected this situation. Although these illustrations were closest to the design media architects usually use, the participants especially appreciated the text (conveying the story).

Figure 4. Persona sheet:

featuring (a) a description of the persona’s character and biography, and

(b) their current use situation, plus room for notes (translated).

In architectural practice, current use issues often remain unknown. Even if architects get to know users’ current situation, this knowledge is hard to share with the team. The current use scenarios provided an opportunity to document current use situations and spread insights among the design team. Use issues were labelled in the margin of the sheets. Although some participants were tempted to jot down quick fixes or concrete associations, many notes contained broader topics that even overarched the individual profiles, like autonomy and social inclusion.

The identified use issues were the starting point for a brainstorm to generate scenarios about ideal futures, linking a place to an activity and feeling. In George’s case, this triggered rather straightforward scenarios, such as adding a fruit orchard to the residential care facility, where he could share his knowledge and all residents could enjoy the fruit and the experience of seasons. In Agnes’s case, generating ideal use scenarios brought the tensions to surface of practical limitations and led to more profound discussions concerning how to conceive and organise care (e.g., grouping versus integrating people with dementia in wards). In an ideal future, Agnes would enjoy afternoon tea and cake in the normal environment of a grand café on the care campus, but this would require someone to accompany her. Similarly, adding a kitchenette to Agnes’s room for her to receive visitors and offer them coffee would conflict with current safety regulations.

These ideal use scenarios contained many references to the larger themes that had been identified in the current use situations. Participants’ use of words like normality or own place/choice evoked a deeper understanding by referring to the personas’ situation and priorities. This understanding echoed the situated, contextualised experience described in the current use scenarios. In the crafting of future use scenarios, the complexity of this user experience was preserved in a condensed way without losing the richness or meaning.

The participants remarked afterwards that being forced to focus exclusively on the aspect of experience was interesting, as it is often crowded out by other design requirements:

In our care projects, we always try to take an approach from [the perspective of] the residents, the staff member, the family, and the general public. […] But in many cases it rather strands… that you mostly depart anyway from the vision of the technical director who sits at the table, a general manager. And yet it’s often approached in a quite rational way, whereas [it] now really [started] from, yes, this experience […] So I think we need to watch over this, that we take a step back for a moment from those square meters and those tables and all those rational approaches. And this methodology completely responds to that. (project director, ArchiSpectrum)

Design Development

A second contribution of the tailored approach concerns the way in which a confrontation with concrete user perspectives supports design development, which became most apparent in workshop 2. This workshop involved mapping user journeys onto the project site and synthesising the findings into recommendations for the next design phases.

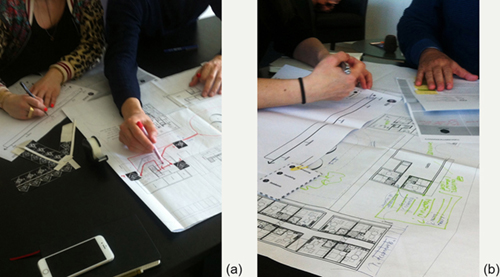

As outlined above, the user journey mapping exercise was intended to confront the design with the personas’ perspectives. For each persona, the participants mapped a typical day on the site, by drawing a route on the plans, analysing the aspects that contributed to his/her spatial experience and pinning their assessment with stickers on the plans for comparison with other perspectives. According to the participants, putting oneself into the user’s shoes was a very good exercise to scrutinise the design in terms of space and time.

I think […] it’s a good thing to put yourself as a designer in the position of the user and almost move through the architecture you design. Personally I think it’s really a fascinating and valuable tool to get to work. (architect, ArchiSpectrum)

The user journey mapping exercise seemed to invite participants to actively explore design options (see Figure 5). The participants did not limit themselves to drawing a route on the plan as instructed (left picture), but also immediately adapted the design (right picture). This included adding functions (e.g., a vegetable garden) or reconsidering their position (e.g., entrances, the grand café terrace, the communal living room) based on a persona’s motivations. Participants’ hands-on interactions with the workshop material illustrates the flexible and dynamic nature of scenario-based design, as they did not feel limited to assessing a fixed design state but implemented their insights. Being adjustable to changes in the design or problem, scenarios proved a good way to investigate implications of design moves.

Figure 5. Participants confronting the design on floor plans:

(a) drawing routes,

(b) making immediate design adaptations, such as adding functions like a vegetable garden.

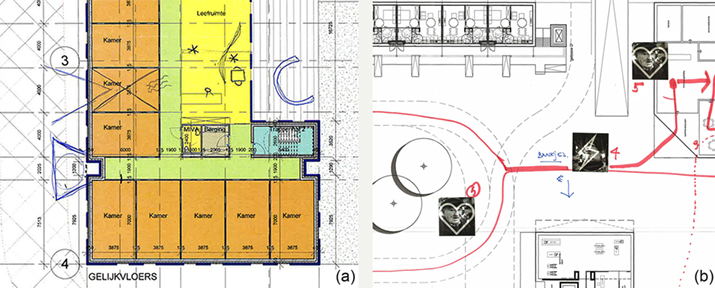

Content-wise, the current and ideal use scenarios provided inspiration for the activities that the personas could undertake when transferred to the project site. The insights into users’ needs made participants add spaces for several functions not accommodated by the current design, like a contemplation room for the remembrance of loved ones (Figure 6a). The personas provided a clear lens for the design. Motivated by Agnes’s fragility, e.g., participants from both firms reflected about spatial qualities in her direct environment. Projecting the personas in a new setting stimulated participants to even take into account the consequences of deteriorating situations. Moreover, mapping personas’ routes provided insight into the spatial relation between the functions on the site. This included, e.g., considering visual connections between spaces and detecting the lack of benches along longer routes for people to rest (Figure 6b). The journey mapping exercise also involved interaction between different personas, such as George picking up Agnes to visit the contemplation room, but such instances were fewer. Overall, the exercise showed the transformative potential of scenarios, as elements from the current use scenarios were reconfigured into a future use scenario.

Figure 6. Examples of design changes motivated by the personas: (a) extending the corridor with a contemplation room (© Plan-A), (b) adding benches for resting with a view (© ArchiSpectrum). Reprinted with permission.

In the workshop exercise that followed, where overall recommendations were drawn up for significant spaces in the project, the concretisation of personas’ interactions with the design helped to disentangle the diversity of use situations and translate these into the design. Whereas the previous exercise revealed how spaces could respond to individual personas’ needs, combining the different personas’ perspectives highlighted the need for versatility in places that accommodate multiple people. For example, the participants put forward that the communal living room of a housing unit needed versatility as to offer the diverse group of future users a variety of spatial qualities and use opportunities. Furthermore, using the timeline helped to reflect on the different ways in which a space could be used throughout the day, which may give rise to different requirements (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The mapping exercise revealed the need for different atmospheres (listing interior aspects) in the cafeteria, serving as a breakfast nook, grand café, and restaurant. © ArchiSpectrum, reprinted with permission.

Combining perspectives also made contradictions become evident. Whereas the residents’ perspectives inspired the idea of providing separate nooks with differentiated atmospheres and activity opportunities in the living room, the staff’s perspective demanded a clear overview for monitoring residents’ safety, quick help, and interaction. Such conflicting use issues were noted for consideration later in the design.

The participants at ArchiSpectrum were even inspired to work with this aspect of diversity on a more fundamental level. They started exploring a modular system of dwelling types in relation to the different types of future residents, also differentiating in location and orientation based on the user profiles. In sum, these examples show how the scenario-based design exercises nourished developing ideas and assessing the design.

Communication

A third contribution of the tailored scenario-based design approach is that it facilitates communication. This became apparent through the course of the workshops and was highlighted in the evaluation session. The participants stressed the added value of attending the workshops as a group, as it provided them with a shared understanding of use issues and a shared reference and language to discuss the design-in-the-making. Indeed, identifying use issues (see Insight) and reflectively assessing the design (see Design Development) was enhanced by the group effort.

As for the design team, the participants appreciated the rather unusual situation of having around the table people with different roles in the architecture firm. They found it interesting to hear different interpretations of use issues and conceptions of the project-to-be and to jointly dwell on the implicit care visions they are materialising.

I thought it was interesting that we were sitting around the table precisely with people with different visions, from different points of view, to hear how they took in these profiles. Because, I have to admit, in that first workshop I heard some people speaking and thought “well, I wouldn’t look at it that way, but what they’re doing is interesting for me, to [take that perspective]” […] I think [the personas and scenarios] are a useful tool to discuss the project […] [Without them] it would become maybe even more abstract. (architect, ArchiSpectrum)

Also appreciated was the presence of the client representative, as this person could easily add practical knowledge to the unfolding understanding of the design problem and solution. The client representatives themselves particularly appreciated the personas and commented that they appeared very familiar. They could easily draw parallels with residents in existing facilities and use this to continuously fill in with missing information. The client representatives suggested concrete roles and activities the personas could take on (e.g., George could be the project manager of the vegetable garden). Throughout the exercise, they helped evaluating design proposals by critically assessing the future use scenarios from their understanding of the personas’ perspective, extended with their experience with residents and staff. They repeatedly commented on and brought up use issues to be addressed in the design (including annotating and highlighting in the workshop materials). Likewise, the participants from the architecture firms thought that the scenario-based design techniques offered the client representatives more insight into the design, as such facilitating communication.

Additional Potential

Whereas the workshops were scheduled during the early conceptual stage, the participants saw opportunities to extend the application of scenario-based design techniques to later design stages and even beyond.

There was a consensus that scenarios hold potential for presenting a final design, especially in the context of design competitions. An architect from the expert panel remarked that design competitions were often decided based on the representation of use aspects, as clients want to be able to imagine and recognize how the building will be used. Whereas clients, as non-experts in architectural design, may have difficulties with design materials, scenarios offer an understandable means of communication. Starting from the perspective of users, they bring a coherent narrative that might be easier to relate to than expert-oriented design rationales. Participating architects remarked that they usually explain the resulting design from the designer’s perspective by going through the sequence of design moves, but they acknowledged that an interesting alternative would be to explain it from the user’s instead.7

Beyond the collaborative workshops, they also saw potential in applying personas and scenarios to structure the dialogue between architects and other stakeholders. Having applied the techniques internally beforehand, architects could use them to make tangible aspects related to user experience in meetings with the client. Scenarios enabled talking through the implications of (alternative) design options with the client in a well-founded and concrete way, as such supporting decision-making. If known by all parties, the personas could provide a way to also involve the perspectives of user groups that are not represented in person.

Participants from the architecture firms also saw potential for scenario-based design techniques at the client side. They suggested clients use the techniques when drafting the project definition, which currently contains little information about user profiles or anticipated use. Especially in the case of briefs for design competitions, the effort to create personas would pay off, as they would be used by multiple design teams. Furthermore, the client representatives themselves saw opportunities for applying scenario-based design techniques in their organization beyond design activities, as when scrutinising the care for and contact with residents.

Another application participants suggested was to map users’ journey in a realised project, such as architects’ own realisations or projects relevant to a certain design assignment. While visiting current buildings and reference projects is already common practice, the spectrum of these building visits usually excludes user experience. Participants remarked that the scenario-based design approach would offer a lens for paying attention to use aspects on site. Mapping the aspects that contribute to people’s experience would support learning from previous projects.

These suggested applications of the techniques all concern complex projects. One architect in the expert panel, however, also saw potential for application in small-scale projects. Even personas representing the residents of a single-family house would be valuable as a communication tool, he claimed. With the clients, they could help making architects’ assumptions explicit, while passing on all information in a condensed and engaging way among the architects on the team.

Challenges

Besides the contributions and potential of the scenario-based design approach, the participants also identified practical challenges to its broader implementation in architecture.

A major concern was time investment, as some participants thought that becoming acquainted with all the personas and doing the exercises with several people was a huge request. To minimise the time investment, however, different participants uttered conflicting suggestions to cut back on the assignments (e.g., spending less time on general themes versus the concrete design). This suggests scenario-based design’s versatility in bringing to the fore use aspects on different levels of abstraction that relate to different priorities in participants’ daily roles (e.g., outlining visions versus working out concrete designs). Just like narrowing the exercise would limit its contribution, reducing the number of participants would compromise the variety of perspectives, which was considered an added value.

The time concern was countered by a different positioning of the exercises. Participants remarked that, if they were considered not as an extra task, but as a concrete language to discuss experience, it only becomes a matter of learning the language—a single effort. Ultimately, scenario-based design could become an integrated way of thinking about all projects.

That the personas were research-based, was considered a particular strength of the scenario-based design workshops (see Insight), but poses the challenge of who will produce them for other types of projects. At first instance, the participants from the firms considered it the client’s task to provide project-specific personas. For architects, generating specific personas for each project would again require a large time investment. However, the personas used in the workshops for residential care projects were considered rich enough to be applied in other types of projects as well. The ArchiSpectrum management even considered creating a regular persona set, the ArchiSpectrum family, which could serve the different projects in the firm, as such maximising the profit.

Some participants also raised concerns about the (in)correct use of scenarios. A pitfall of the technique could be to present artificial ideal futures where personas were sculpted to match overly positive narratives, which may block generating novel ideas. In both firms some participants experienced this tendency with the client representatives, who were more used to this marketing approach of presenting a project’s advantages to future residents. However, the real benefit of the scenarios for architectural design lies in its critical approach. Exactly the confrontation with users’ perspectives (and especially the most challenging ones) might help anticipate use issues and as such push the design.

Discussion

Situating the Findings & Contributions

Starting from the observation of the problematic position of users in architectural design, this study proposes a scenario-based design approach to support architects in addressing user experience, by manifesting experiential aspects of architecture. Table 2 positions the potential for architectural design of this approach in relation to the challenges of architects’ current design practice based on the findings reported above. Below, the mechanisms of the approach are further teased out in the light of related literature.

Table 2. Comparison between a traditional and scenario-based design approach in architecture.

| Challenges in architects’ current practice | Potential of scenario-based design |

| Limited access to user perspectives (with limited resources for research) |

Research-based, vivid documentations of users and current use situations, to which stakeholders can add |

| Limited insight into intangible use issues and visions (e.g., through project definition); Limited attention to diversity |

Condensed reference to situated, contextual experiences (fostering more engagement); Focus on diversity and dynamics of use |

| Implicit attention to experiential aspects in design; Dominance of rational approaches in decision-making |

Explicit exploration of implications and motivation of design decisions in terms of user experience |

| Underrepresentation of use(rs) in communication (with often difficulties in communication with clients and sharing knowledge in the team) | Shared frame of reference in the design team; Understandable communication with non-designers from user perspectives |

| Limited learning from realised buildings | A lens for paying attention to use aspects and then feeding this back into the design (e.g., briefing or evaluation) |

Analysing the scenario-based design workshops conducted in two architecture firms suggests that explicit attention to use(rs) can enrich the diversity of qualities considered during design. In current architectural practice, explicit attention to potential users tends to be either associated exclusively with design for the special needs of a certain target group, or dismissed based on the idea that architecture for a general (super diverse and ever-changing) public does not need attention to specific user profiles (Van der Linden et al., 2018). However, our study challenges this practice by postulating that even dynamic and diverse use situations can be incorporated in design if a flexible frame of reference is built (see van der Bijl-Brouwer & van der Voort, 2014b).

The scenario-based design approach, and especially the personas, actually seemed to engage participants in considering use aspects that otherwise remain unexamined. As such the techniques may support a more holistic and socially engaged approach to design, opposing predominantly rational approaches: “Current practices tend to fall short in several respects: Designers and users are not truly engaged; social and political aspects are filtered out; and complexity and representativeness are difficult to identify and portray.” (Grudin & Pruitt, 2002, p. 144)

While scenarios as use descriptions tie in with architects’ current way of working, the personas as elaborated and distinguished characters provide a motivation (the goal element in the scenario) external to the designers’ own beliefs (cf. Nielsen, 2013). As such they challenge designers’ assumptions and prevent self-reference (Miaskiewicz & Kozar, 2011), which characterises common practice in architectural design (Till, 2009). Giving a face to use issues, the personas are a way to literally populate architectural design (cf. Imrie, 2003). Both participants from the architecture firms and the client representatives appreciated the scenario-based design approach for repeatedly redirecting attention to user experience.

The personas and scenarios transferred knowledge from other perspectives (that might be difficult to access), and furthermore guided problem setting and idea generation. Browsing the personas and current use scenarios seemed to help participants in selecting particular features of the problem spaces (naming) and identifying areas of the solution space (framing) (cf. Schön, 1983). The lens through which a design is approached determines how it is developed, as it imposes a coherence that guides subsequent design moves (Schön, 1988). In this sense, scenario-based design can be considered an instrument of inquiry:

instruments of inquiry […] not only augment designers’ ability to carry out certain actions, but also augment their cognitive abilities to see and understand certain design opportunities, conceive of and evaluate possible solutions, and bring potential futures into form so they can be examined and communicated. (Dalsgaard, 2017, p. 21)

Beyond providing insight into alternative experiences, scenario-based design functions as a vehicle to connect use aspects to architects’ own experience and vision, making values (e.g., about care) of individuals and firms explicit and hence deployable in discussions. Manifesting aspects related to user experience, which usually remain implicit, yields a shared understanding that benefits decision-making (Steen, Buijs, & Williams, 2014; van der Bijl-Brouwer & van der Voort, 2014a).

Limitations & Further Development

The test of the tailored scenario-based design approach was limited to projects in the conceptual design stage. This made the exercises at times quite conceptual too—at several points the design was not concrete enough for critical confrontation. Participants needed to park more specific concerns until a later design stage, when decisions regarding, e.g., the interior would be discussed in more detail. Based on the tests in the conceptual stage, we cannot make claims about later design stages. When asked about the ideal timing of the workshops, participants mentioned both earlier, so as to inform concepts as much as possible, and (again) later, so as to treat more detailed interactions.

Moreover, the brief intervention of the workshops did not allow us to observe whether there is any long-term impact on the design or the design process. Actually, the outcome of workshop 2 only provided a starting point for further discussion. Participants indicated they would have preferred an extra phase or workshop for decision-making based on collaboratively comparing scenarios for the different personas. In this article, we combined initial observations from the tests with participants’ statements on the potential of the approach compared to their usual way of working. The exact gains for the design projects are yet to be identified. However, the enthusiasm of both participants and the expert panel suggests that the approach is viable and highlights in any case that there is need for more structural ways to involve users’ perspectives in architectural design. In this respect it is promising that both firms reported to be adopting the techniques in other projects as well. The abovementioned need is also illustrated by the requests for input on user experience we receive from architecture firms, and to which we respond by offering scenario-based design workshops, in the context of residential care projects and beyond (e.g., humane detention).

Certainly, more tests are needed to further develop the concrete form of the exercises. Participants could not give substantial feedback on the concretisation of the techniques. Further testing should be more extensive and diverse, with iterations in different project types and design stages and with different materials and groups of participants. Based on the initial workshops reported here, in future workshops we are implementing an additional exercise to map (on different levels of the design) conflicts between different user perspectives that arise in key scenarios in relation to personas’ main motivations. This can foster participants’ critical approach and provide explicit argumentation for decision-making. Moreover, in this way not all (diverse) participants need to be present during all exercises. While diversity in the composition is maintained, time investment could decrease to the crucial phases of building shared understanding and decision-making.

If the scenario-based design approach is to be sustained, the enduring relevance of personas is crucial. The research-based personas that were offered could surpass questions of research quality standards, keeping the persona set updated and appropriate requires more attention. Whereas some participating architects were enthusiastic to create their own persona set, we suppose that the most realistic option in current architectural practice is that clients take on the investment of (involving researchers in) creating personas that communicate the project’s ambitions and cover the spectrum of diversity. A next step in the research is therefore to develop a roadmap for architects and clients, offering guidance to flexibly adopt scenario-based design techniques (e.g., the crafting of personas and scenarios) and integrate them into (user) research, briefing, design and presentation activities.

Conclusion

In current architectural design practice, user experience is a largely implicit dimension, being typically addressed through assumptions, self-reference, and limited informal methods (Imrie, 2003; Van der Linden et al., 2018; Verhulst et al., 2016), which makes it hard to be discussed and diversified beyond architects’ personal experience. In addressing user experience explicitly, scenario-based design has the potential to support architects’ design process in several ways: it provides insight by framing goals and enabling concept generation; it contributes to design development by promoting reflection and guiding assessment of potential solutions; and it facilitates communication by articulating assumptions and reorienting rationales. Within the unstructured complexity of design projects and their requirements, scenarios offer various stakeholders a way to integrate information about users, settings, designed spaces, and their interactions into a coherent story, so that use issues and solutions can be discovered and anticipated earlier on.

Based on the test workshops’ findings, we conclude that there is enough resonance with the application and identified contributions in other design disciplines (Carroll, 2000) to adopt scenario-based design in architecture. There is high potential in transferring the scale of the scenario-based design techniques, with narratives encompassing larger frames of time and space. However, more work is needed to develop concrete tools and guidance to integrate the approach sustainably. The development of a scenario-based design roadmap could benefit from research on how to document spatial experience and relating architectural qualities, and broadening the scope from the architects’ design process to phases of user research and design briefing.

Architects’ concern for the open-endedness of their designs deserves a final note. In current architectural design practice, the need for taking into account wide and dynamic spectra of use, users, and contexts, has caused little urge to consider specificities (Van der Linden et al., 2018). However, with the vague aim to design for the general everyone, designers are only equipped to design for themselves (cf. Oudshoorn, Rommes, & Stienstra, 2004). The evaluation of the test workshops suggests that everyone can be operationalised through scenario-based design, without falling into the narrowness of targeted marketing approaches. Populating architectural design with specific characters and integrating individual insights allows teasing out otherwise implicit and often contradictory use aspects and supports motivated decision-making. This study can inspire designers from related disciplines to rethink the contributions, pitfalls, and broader application of scenario-based design.

For architects and their stakeholders, scenario-based design provides an opportunity to put soft issues like user experience on the table. Involving implicit knowledge, which is distributed among participants, these aspects are easily obscured by more technical issues. Based on the test workshops we can conclude that scenario-based design offers a technique to scaffold architects’ process of taking on board users’ perspectives. Especially in the case of projects with unfamiliar users and contexts, such as residential care environments, this can support architects in designing spaces that address the challenges of a diverse society and ageing population.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the architecture firms and their clients for offering us a test plot and for their enthusiastic participation. The personas in the workshops are based on research conducted in the Research[x]Design group, which was kindly made available by our fellow (student) researchers: Koen Coomans, Simone Pizzagalli, Anouk Rams, Liesbeth Schreurs, Liesl Van Hecke, Iris Van Steenwinkel, and Peter-Willem Vermeersch. We particularly want to thank our colleagues Margo Annemans, Jorgos Coenen, Dries Dauwe, and Liesbeth Stam for their contributions in preparing, conducting and/or evaluating the workshops, and Kristof Vaes (University of Antwerp) for his advice on the first draft workshop set-up. This research received funding from Flanders Innovation and Entrepreneurship and through a PhD Fellowship of the Research Foundation–Flanders (FWO).

Endnotes

- 1. This exploration transcends the scope of this article, hence will be reported elsewhere.

- 2. For an exception, see the use of personas in energy renovations in Haines & Mitchell (2014).

- 3. We introduce personas here after explaining scenarios (which relate most to architects’ current practice), but consider both equally important and closely intertwined. In scenario-based design literature, there are authors who present personas as an extension to scenarios and vice versa. The former consider personas an elaborated actor that fosters engagement and sense of reality (e.g., Grudin & Pruitt, 2002). The latter consider scenarios a technique to operationalise the persona in the design and imagine use (e.g., Nielsen, 2013).

- 4. For reasons of confidentiality, the firm names have been replaced by pseudonyms.

- 5. Since one architect could not make it to the expert panel meeting, he provided feedback in a separate expert interview.

- 6. The personas are not one-on-one reflections of participants in the research on residential care environments. As user profiles, they condense and portray themes that were found significant to design and relevant to multiple participants. The personas were further fleshed out with anecdotes and personal details of individuals involved in the studies. This approach aims to improve the persona quality and avoid stereotypical or one-sided personas.

- 7. Both firms referred to a previous design competition where they had used a kind of user profile to illustrate the building’s future use as a strategy to address the client. These profiles were however neither particularly elaborated nor used in the design process.

References

- Anggreeni, I. (2010). Making use of scenarios: Supporting scenario use in product design (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands.

- Blythe, M. A., & Wright, P. C. (2006). Pastiche scenarios: Fiction as a resource for user centred design. Interacting with Computers, 18(5), 1139-1164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2006.02.001

- Bødker, S. (2000). Scenarios in user-centred design—Setting the stage for reflection and action. Interacting with Computers, 13(1), 61-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0953-5438(00)00024-2

- Bromley, E. (2012). Building patient-centeredness: Hospital design as an interpretive act. Social Science & Medicine, 75(6), 1057-1066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.037

- Buse, C., Nettleton, S., Martin, D., & Twigg, J. (2017). Imagined bodies: Architects and their constructions of later life. Ageing & Society, 37(7), 1435-1457. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X16000362

- Carroll, J. M. (2000). Five reasons for scenario-based design. Interacting with Computers, 13(1), 43-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0953-5438(00)00023-0

- Cooper, A. (2004). The inmates are running the asylum: Why high-tech products drive us crazy and how to restore the sanity. Indianapolis, IN: Sams.

- Crilly, N., Maier, A., & Clarkson, P. J. (2008). Representing artefacts as media: Modelling the relationship between designer intent and consumer experience. International Journal of Design, 2(3), 15-27.

- Cuff, D. (1989). The social art of design at the office and the academy. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 6(3), 186-203.

- Dalsgaard, P. (2017). Instruments of inquiry: Understanding the nature and role of tools in design. International Journal of Design, 11(1), 21-33.

- Følstad, A., & Kvale, K. (2018). Customer journeys: A systematic literature review. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 28(2), 196-227. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-11-2014-0261

- Fulton Suri, J. (2003). The experience of evolution: Developments in design practice. The Design Journal, 6(2), 39-48. https://doi.org/10.2752/146069203789355471

- Fulton Suri, J., & Marsh, M. (2000). Scenario building as an ergonomics method in consumer product design. Applied Ergonomics, 31(2), 151-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-6870(99)00035-6

- Grudin, J., & Pruitt, J. (2002). Personas, participatory design and product development: An infrastructure for engagement. In T. Binder, J. Gregory, & I. Wagner (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Biennial Participatory Design (pp. 144-161). Malmö, Sweden: CPSR.

- Gutman, R. (Ed.). (1972). People and buildings. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Haines, V., & Mitchell, V. (2014). A persona-based approach to domestic energy retrofit. Building Research & Information, 42(4), 462-476. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2014.893161

- Imrie, R. (2003). Architects’ conceptions of the human body. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 21(1), 47-65. https://doi.org/10.1068/d271t

- Koskinen, I., Mattelmäki, T., & Battarbee, K. (Eds.). (2003). Empathic design: User experience in product design. Helsinki, Finland: IT Press.

- Miaskiewicz, T., & Kozar, K. A. (2011). Personas and user-centered design: How can personas benefit product design processes? Design Studies, 32(5), 417-430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2011.03.003

- Miaskiewicz, T., & Luxmoore, C. (2017). The use of data-driven personas to facilitate organizational adoption – A case study. The Design Journal, 20(3), 357-374. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1301160

- Nielsen, L. (2002). From user to character – An investigation into user-descriptions in scenarios. In B. Verplank, A. Sutcliffe, W. Mackay, J. Amowitz, & W. Gaver (Eds.), Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques (pp. 99-104). New York, NY: ACM.

- Nielsen, L. (2013). Personas – User focused design (pp. 99-125). London, UK: Springer.

- Oudshoorn, N., Rommes, E., & Stienstra, M. (2004). Configuring the user as everybody: Gender and design cultures in information and communication technologies. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 29(1), 30-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243903259190

- Oygür, I. (2018). The machineries of user knowledge production. Design Studies, 54, 23-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2017.10.002

- Redström, J. (2012). Introduction: Defining moments. In W. Gunn & J. Donovan (Eds.), Design and anthropology (pp. 83-99). Surrey, UK: Ashgate.

- Sanders, E. B.-N. (May 13, 2009). Exploring co-creation on a large scale: Designing for new healthcare environments. Presented at the Symposium on Designing for, with, and from user experience. TU Delft, the Netherlands. Retrieved from https://studiolab.ide.tudelft.nl/studiolab/contextmapping/files/2013/01/CM5-2.-Sanders.pdf

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Schön, D. A. (1988). Designing: Rules, types and words. Design Studies, 9(3), 181-190. https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-694X(88)90047-6

- Steen, M., Buijs, J., & Williams, D. (2014). The role of scenarios and demonstrators in promoting shared understanding in innovation projects. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 11(1), 1440001:1-21. https://doi.org/10.1142/S021987701440001X

- Till, J. (2009). Architecture depends. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- van der Bijl-Brouwer, M., & van der Voort, M. C. (2013). Exploring future use: Scenario based design. In C. de Bont, E. den Ouden, H. N. J. Schifferstein, F. Smulders, & M. C. van der Voort (Eds.), Advanced Design design methods for successful innovation (pp. 56-77). The Hague, the Netherlands: Design United.

- van der Bijl-Brouwer, M., & van der Voort, M. C. (2014a). Establishing shared understanding of product use through collaboratively generating an explicit frame of reference. CoDesign, 10(3-4), 171-190. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2014.963125

- van der Bijl-Brouwer, M., & van der Voort, M. C. (2014b). Understanding design for dynamic and diverse use situations. International Journal of Design, 8(2), 29-42.

- van der Linden, V., Dong, H., & Heylighen, A. (2018). Architects’ attitudes towards users: A spectrum of advocating and envisioning future use(rs) in design. ARDETH, 2, 197-216. https://doi.org/10.17454/ARDETH02.12

- van der Linden, V., Dong, H., & Heylighen, A. (in press). Tracing architects’ fragile knowing about users in the socio-material environment of design practice. Design Studies. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2019.02.004

- van der Linden, V., van Steenwinkel, I., Dong, H., & Heylighen, A. (2016). Designing “little worlds” in Walnut Park: How architects adopted an ethnographic case study on living with dementia. In P. Lloyd & E. Bohemia (Eds.), Proceedings of the Conference on Design + Research + Society - Future-Focused Thinking (Vol. 8, pp. 3199-3212). Brighton, UK: Design Research Society.

- Verhulst, L., Elsen, C., & Heylighen, A. (2016). Whom do architects have in mind during design when users are absent? Observations from a design competition. Journal of Design Research, 14(4), 368-387. https://doi.org/10.1504/JDR.2016.082032

- Wright, P., & McCarthy, J. (2010). Experience-centered design: Designers, users, and communities in dialogue. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool.