Designing Objects with Meaningful Associations

Daniel Orth 1,*, Clementine Thurgood 2, and Elise van den Hoven 1,3,4,5

1 Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, Australia

2 Faculty of Health, Arts and Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia

3 Department of Industrial Design, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, the Netherlands

4 Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, University of Dundee, Dundee, Scotland

5 ARC Centre of Excellence on Cognition and its Disorders, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

Objects often become cherished for their ties to beliefs, experiences, memories, people, places or values that are significant to their owner. These ties can reflect the ways in which we as humans use objects to characterise, communicate and develop our sense of self. This paper outlines our approach to applying product attachment theory to design practices. We created six artefacts that were inspired by interviews conducted with three individuals who discussed details of their life stories. We then evaluated the associations that came to mind for our participants when interacting with these newly designed artefacts to determine whether these links brought meaning to them. Our findings highlight the potential of design to bring emotional value to products by embodying significant aspects of a person’s self-identity. To do so, designers must consider both the importance and authenticity of the associations formed between an object and an individual.

Keywords – Attachment, Emotional Value, Life Stories, Object Associations, Product Design, Self-Identity.

Relevance to Design Practice – This paper provides a process for applying product attachment theory to bespoke product design practices with several examples of artefacts resulting from this process. It also provides an evaluation of the resulting artefacts to advance discussion of appropriate means of designing for attachment in product design.

Citation: Orth, D., Thurgood, C., & van den Hoven, E. (2018). Designing objects with meaningful associations. International Journal of Design, 12(2), 91-104.

Received March 12, 2017; Accepted February 5, 2018; Published August 31, 2018.

Copyright: © 2018 Orth, Thurgood, & van den Hoven. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

*Corresponding Author: daniel.orth@uts.edu.au

Daniel Orth is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology of the University of Technology Sydney. His research focuses on designing for product attachment and the intersection between physical and digital products. Daniel previously worked as an industrial designer, developing design solutions with global retail clients. His research interests include emotional design, self-identity, product consumption and human-centred design.

Clementine Thurgood is a Lecturer in Design Factory Melbourne and the Faculty of Health, Arts and Design, Swinburne University of Technology. She was previously a postdoctoral research fellow in the Design Innovation Research Centre of the University of Technology, Sydney. Clementine obtained a bachelor’s degree (hons) in psychology and psychophysiology and a PhD in Experimental Aesthetics from Swinburne University of Technology. Her research interests include design innovation, design methods and tools, design thinking and aesthetics.

Elise van den Hoven is a Professor in the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology of the University of Technology Sydney and Associate Professor in the Department of Industrial Design of the Eindhoven University of Technology. She has two honorary appointments: honorary senior research fellow at the Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design, University of Dundee, and associate investigator with the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence in Cognition and its Disorders. Elise is the project leader of Materialising Memories, a research program that aims to design for improved reliving of personal memories. Her research interests include human-computer interaction, interaction design, tangible and physical interaction, people-centred design and supporting human remembering activities.

Introduction

Product attachment has been extensively studied across a range of disciplines with contributions made to advance theory on why and how people come to cherish their belongings. It is generally understood that people develop an attachment to an object for its role in the construction, maintenance or development of an aspect of their self-identity (Ball & Tasaki, 1992; Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton, 1981; Schultz, Kleine, & Kernan, 1989; Wallendorf & Arnould, 1988). These objects can be used to express personal values, engage in fulfilling activities or reflect ties to friends and family.

While substantial contributions have been made to advance our understanding of why and how people develop an attachment to their possessions, little progress has been made towards applying this theory to design practice. Efforts to bridge this gap between theory and practice have primarily been made in one of two ways. Firstly, by evaluating existing user-product relationships to formulate design strategies for promoting attachment (see Mugge, Schoormans, & Schifferstein, 2009; Niinimäki & Koskinen, 2011; Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008). Secondly, through the process of creating product concepts or artefacts seeking to promote attachment among users and to evaluate their success in doing so (see Desmet, Overbeeke, & Tax, 2001; Lacey, 2009; Van Krieken, Desmet, Aliakseyeu, & Mason, 2012; Zimmerman, 2009). Studies that evaluate user relationships with existing possessions often point towards meaningful memories and associations as key determinants for strong degrees of attachment (Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton, 1981; Kujala & Nurkka, 2012; Page, 2014). Despite their prevalence in the product attachment literature, the potential value of using meaningful memories and associations to promote product attachment has not yet been explored in design practice.

We adopted a research through design (Frayling, 1993) approach to investigate whether it is possible to purposefully create meaning by evoking meaningful associations. The article outlines our process in applying product attachment theory to the design of six bespoke artefacts inspired by interviews conducted with three individuals who discussed details of their life stories. Each artefact was designed with the goal of containing meaningful associations to aspects of the intended user’s self-identity and life narrative. We evaluated the associations that came to mind for each participant while interacting with the designed artefacts to determine whether these ties brought meaning to them. We reflect on our design process to discuss the effectiveness of our approach and the resulting artefacts in promoting the formation of meaningful associations with objects. We conclude by exploring the applicability and limitations of our findings alongside existing design strategies for promoting attachment.

Product Attachment and the Self

The link between cherished objects and the self has been the focus of many studies in the fields of psychology, sociology, material culture and consumer behaviour (e.g., Belk, 1988; Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton, 1981; Myers, 1985). There is a level of agreement among these researchers regarding the strong ties between people forming attachments to things and the ways in which humans construct, develop and maintain a sense of self. Belk’s advancement of the notion of the extended self in which an individual’s sense of self extends beyond what is me to what is mine has become a central component of product attachment theory.

Attachment in this context has been defined as “the extent to which an object which is owned, expected to be owned, or previously owned by an individual, is used by that individual to maintain his or her self-concept” (Ball & Tasaki, 1992, p. 158). This definition distinguishes attachment from other consumer behaviour constructs for its associations to the self. While this view of attachments as self-extensions is shared by several researchers (see Kleine & Baker, 2004; Schultz et al., 1989; Thomson, MacInnis, & Park, 2005), it has also been contested by Schifferstein and Zwartkruis-Pelgrim (2008) who argue that product attachment is a similar yet separate concept to self-extension. Nevertheless, they acknowledge the relevance of identity, using Greenwald’s (1988) four facets of the self-schema—the diffuse self, the private self, the public self and the collective self—as a basis to measure attachment.

Product attachment has been shown to relate to the emotional ties that form between users and their belongings (Mugge, Schifferstein, & Schoormans, 2005). Schultz et al. (1989) found these ties often involve positive emotions for the belongings to which people experience a strong degree of attachment. The strength of the attachment felt by an individual towards an object often changes over time (Myers, 1985). While the formation of attachment often develops slowly through ongoing interactions (Page, 2014), an object may also evoke an immediate emotional response. This can occur as a family heirloom is passed down through the generations or in response to the receipt of a thoughtful gift from a loved one (Kleine, Kleine, & Allen, 1995).

Several advancements in identity theory have also influenced product attachment theory due to the closeness of these two areas of research. This includes the structuring of a person’s sense of self as a life narrative (McAdams, 1985) in which moments from our past, present and anticipated future are connected to construct a coherent life story that reflects who we are as a person. Products therefore can gain emotional significance for their involvement in a person’s life story (Kleine et al., 1995). This includes products that reflect a person’s autonomy as a unique individual, their affiliations to friends and family, fond recollections of the past or their hopes for the future. Govers and Mugge (2004) similarly emphasise the role played by an individual’s sense of self in their development of attachment to products, finding that people were more likely to form attachment to products they perceived to possess personality characteristics similar to their own.

Object Associations

Discussion in product attachment literature often refers to the associations that people assign to a possession. An object can hold meaning for its ties to significant memories, experiences, people, places or values. In their study of meaningful product relationships, Battarbee and Mattelmäki (2004) propose meaningful associations as one of three overarching categories for meaningful products alongside meaningful tools and living objects. Mugge, Schoormans, and Schifferstein (2008) suggest four possible determinants of product attachment: pleasure, self-expression, group affiliation and memories, of which all but pleasure are associative in nature. In reference to long-lasting emotional feelings towards objects, Norman (2004) proposes that “what matters is the history of interaction, the associations that people have with the objects and the memories they evoke” (p. 46). In this way, attachment to things often develop from properties beyond their materiality, extending to their links to aspects of the self or the life narrative of an individual.

The associations that people assign to their things can come about in several ways (Kujala & Nurkka, 2012). They can arise from the history of ownership and use of a possession, perceptions of its materiality such as form, colour, texture, size and smell or from beliefs held by the individual about the kinds of people who would own or use the product (Allen, 2002). The nature of these associations can vary from abstract to concrete, fitting within a spectrum from indistinct values or feelings to specific memories. The resulting image that comes to mind in regard to an object is often complex and obscure as it encompasses associations from all aspects of the product experience.

In their extensive review of identity literature, Reed, Forehand, Puntoni, and Warlop (2012) argue that one’s sense of self is made up of a number of identities, each with their own bundle of associations that define what it means to be or not be that type of person. These identities and their respective characteristics influence the likelihood of the associations that individuals assign to a particular product being considered meaningful (Fazio, 2007). For example, a car enthusiast will more readily develop meaningful associations to a new car model than someone with little interest in cars. Possessions can also hold associations to multiple identities to varying degrees (Deaux, Reid, Mizrahi, & Ethier, 1995). This can be seen with a bicycle being associated with both personal fitness and membership within a local cycling club. In this way, objects can develop layers of meaning for their owner with ties to several emotionally significant aspects of their self-identity (Orth & van den Hoven, 2016).

Links between a product and an individual’s sense of self can act as a primary reason for the significance ascribed to the product. The ways in which a person infers associations as they perceive a product provides designers with opportunities to promote the formation of meaningful user-object relationships through careful consideration of various design elements.

Designing for Product Attachment

Designing products that people are more likely to assign emotional value has been viewed to provide several benefits, including empowering owners in developing and maintaining a coherent sense of self (Wallendorf & Arnould, 1988), providing people with self-expressive opportunities (Mugge, Schifferstein, & Schoormans, 2005) and the potential for more sustainable consumer behaviour by increasing product lifetime (Chapman, 2009). These benefits have led many design researchers to search for ways in which designers may be able to promote the formation of attachment to the products they create.

A number of possible determinants for product attachment have been suggested with recurring themes related to memories, enjoyment, self-image, group affiliations, utility and appearance (Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton,1981; Mugge et al., 2005; Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008). From these determinants, a range of design strategies for facilitating attachment have been proposed. Schifferstein and Zwartkruis-Pelgrim suggest that designers should aim to create products that evoke enjoyment or facilitate personal associations. Mugge et al. propose two strategies for designers: stimulating social contact and incorporating odours as ways of encouraging associations with others and product-related memories. Further evaluative studies have since highlighted memories or personal associations as a primary determinant for strong degrees of attachment yet acknowledge the difficulty of utilising this within a design process (Niinimäki & Koskinen, 2011; Page, 2014). These studies provide promising avenues for designers seeking to promote attachment in their practice but the effectiveness of these strategies remains unverified.

Several researchers have designed novel objects with an emphasis on emotional significance (see Desmet et al., 2001; Lacey, 2009; Van Krieken et al., 2012; Zimmerman, 2009). In their efforts to add emotional value to mobile phones through design decisions, Desmet et al. conclude that no single product will have emotional value for all intended users, suggesting the need for custom design practices. Lacey similarly emphasises the impact of individual preferences, proposing that designers should allow consumers choice within a set of objects to increase the likelihood of attachment to mass produced products. While tools have been developed to evaluate people’s emotional reactions to products (e.g., Desmet, 2003; Kujala & Nurkka, 2012), evaluating the effectiveness of designed artefacts in fulfilling goals related to the formation of attachment remains a difficult challenge for design researchers.

In this paper, we build on existing product attachment literature by exploring the potential value of utilising meaningful associations in design practice. We designed, created and evaluated objects intended to contain links to an individual’s sense of self through an examination of their life narrative and existing cherished possessions. In doing so, we aim to address gaps in understanding of the consequential value of applying strategies derived from product attachment theory to design practice.

Method

As our research goals related to bridging the gap between product attachment theory and design practices, we chose to apply a research through design approach (Frayling, 1993), creating a range of bespoke artefacts intended to contain meaningful associations with aspects of the participant’s self-identity and life narrative. In this section, we provide an overview of the procedure we developed for the three phases of our study. Each of the three phases involved in our process is then described in greater detail together with the resulting findings in the subsequent section.

A total of six artefacts was created based on the life narratives of three individuals. As our focus was on creating objects that could be used in constructing a coherent life story, we chose participants in middle adulthood, between 45 and 65 years old. We believed this demographic would possess a rich life history while still holding anticipations for their future with the changes that come with retirement. Participants were recruited from the broader social networks of the researchers.

Phase 1: Inspiration

We conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews in which we asked participants to discuss their life stories (Linde, 1993). These interviews were intended to reveal details of the participant’s identity narratives, much like the work of Ahuvia (2005), which investigated the life history and loved possessions of ten individuals. We saw life stories as an appropriate means of gaining an understanding of participants’ lives and individuality as they “express our sense of self” (Linde, 1993, p. 3). It is worth noting that life stories are reconstructions of a person’s experiences that are both subjective and fragmented in nature (Polkinghorne, 1995). A life story is also a social unit exchanged between people through conversation and the re-telling of past experiences. We acknowledge that our interviews are limited in the breadth, depth and continuity of information they provide, capturing mere glimpses of the re-presented lives of our participants. Nevertheless, the life stories shared with us still provide a wealth of rich data to inform the subsequent phases of our study.

Interview questions followed three distinct areas. Firstly, we began by asking participants to share their life narrative, directing discussion from their childhood to their current life and finally their plans and aspirations for the future. Discussion pertaining to participants’ life narratives comprised the majority of the interviews. Secondly, we asked them to discuss things they deemed personally significant, including traits they valued in others and their ties to people, places, experiences and possessions. Finally, we concluded by asking participants to share their thoughts on various physical properties such as colour, texture and material. Interviews were conducted in the homes of participants and ranged from one to two hours. All participants appeared at ease in their response to questioning, openly sharing personal stories, values and aspirations throughout the interviews.

Phase 2: Creation

We used the stories shared by our participants as inspiration for the design of several artefacts. Our design process followed the goals of Zimmerman’s (2009) philosophical stance of designing for the self, which “asks designers to make products as intentional companions in a user’s construction of a coherent life story” (p. 396). We aimed to translate elements of the participant’s life narrative and sense of self to the designed artefact. This translation was intended to facilitate the formation of emotional value in the artefact through its ability to characterise and communicate significant memories, experiences and values held by the user.

In our analysis of the interviews, we first transcribed the data and extracted stories, experiences and values that held potential for their significance or ties to physical characteristics that could be translated into an artefact. Selected data was then coded for its links to aspects of the self-identity or life story of the individual, for example, a past personal achievement or an ongoing mother-daughter relationship. We then created several clusters of data that could be merged into singular design concepts. These clusters were judged for the significance, clarity and number of associations that could be incorporated into our design process. Finally, we selected the two most promising clusters from each of our three participant interviews to resolve into six designed artefacts.

To appropriately express the values and meanings that came from our participants’ life stories into a physical artefact, we gained insight from Hekkert and Cila’s (2015) analysis of product metaphors. Much like product metaphors that translate “abstract concepts into concrete product properties” (p. 199), we used imagery from our interviews with participants to shape our designs. This translation process was not intended to create artefacts that merely mimic the stories shared by our participants, but for our artefacts to be meaningful in the eyes of their user. This goal is both ambitious and difficult to measure. In discussing design that attempts to induce emotions or experiences for users, Hassenzahl (2004) states that designers “can create possibilities but they cannot create certainties” (p. 47), a sentiment that we agree with.

All artefacts were created by the first author, an industrial designer with several years of industry experience. The ideation process was conducted in a similar manner to traditional design practice with a range of sketched concepts explored prior to the creation of the final six artefacts. Stories, experiences and values shared by our participants during interview sessions were highly effective in providing inspiration and direction for the design process.

Phase 3: Evaluation

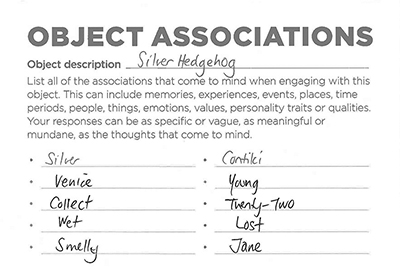

To evaluate the effectiveness of our designed artefacts in developing meaningful associations for the user, we devised Object Associations cards (see Figure 1) that asked participants to list all associations that come to mind when engaging with a specific object including memories, experiences, events, places, time periods, people, things, emotions, values, personality traits or qualities. Our instructions promoted the inclusion of responses ranging from specific to vague or from meaningful to mundane. We asked participants to complete an Object Associations card for three of their self-selected cherished possessions at the start of our initial interview sessions to gain an understanding of the types of associations they ascribed to their valued belongings. Participants were later given three of the six designed artefacts and asked to complete an Object Associations card for each received artefact over a two-week period.

Figure 1. Example of an Object Associations card.

Each participant received the two artefacts designed without their knowledge from their own shared narratives and one designed from the narrative of another participant. In determining which of the artefacts designed for another participant they should receive, we selected the artefact that we believed most closely aligned with their identity. Participants were asked to incorporate each of the received artefacts into their normal routines throughout the two-week period. We concluded by conducting a second interview with each participant to discuss their reactions and the associations they listed for each of the artefacts they received. These evaluative interviews were transcribed and analysed alongside reflections on the design process to determine the effectiveness of our approach.

The study was introduced to participants as an exploration of the thoughts that objects can bring to mind. Participants were not given any information regarding the source of inspiration for the artefacts they received or our design intentions until they had completed their involvement in the study. We wanted our participants to infer the associations or meanings of the designed artefacts on their own accord. Knowledge of our design intentions could have influenced the responses provided by our participants (cf. Da Silva, Crilly, & Hekkert, 2015).

Design Process and Findings

We present our findings within the three phases of the devised design process: gaining inspiration, creating the artefacts and evaluating participant responses. Findings from each of our participants are treated in isolation to maintain the depth and diversity that came from their involvement.

Phase 1: Inspiration

In this section, we provide a brief overview of each of the life narratives re-presented in the interview sessions. These semi-structured interviews discussed participants’ past experiences, current lifestyle and hopes for the future.

Alex’s Life Narrative

Alex is a 56-year-old father of three with a career in IT sales and client management. He lives with his partner near the northern beaches of Sydney. Alex’s upbringing was fickle as his family moved around Australia every few years to follow his father’s professional role in the army: “there was always something different going on—different house, different town, different school friends.” This nomadic lifestyle continued in his adult life as he lived and worked in various countries across the globe and developed a passion for travel.

While these ongoing movements across the globe bring volatility, Alex has maintained continuity in his life through his social connections: “I’m a communicator […] I write to people […] I’ve always made the effort to keep in contact with my friends.” Alex brings continuity to his wealth of travel experiences through his belongings. His home is filled with refined objects of art, paintings and books that act as souvenirs of his travel experiences.

Despite having a successful career, Alex separates his professional life from his sense of self: “I don’t define myself by my career […] I’ve worked very hard at it but it hasn’t been the central part of my being.” This disassociation between Alex’s career and his identity coincides with his anticipations for the future following retirement, freeing time for writing, travelling and being a pro-active granddad.

Louise’s Life Narrative

Louise, 48, is a mother of two working in human resources. She grew up in a rural town on the east coast of Australia, accustomed to being out in the surrounding bushland with her older brother: “we used to spend a lot of time out in the bush. We were fairly conservative kids.” Both of Louise’s parents worked at the local high school, which brought about certain responsibilities: “we really knew the boundaries and I think we were also conscious of not embarrassing our parents.”

Louise eventually left home to attend university in another rural town 400 kilometres away, giving her a strong sense of freedom. She has since lived and worked in various Australian cities and enjoys travelling with her husband and two children. Looking forward into the future, Louise hopes to return to living in a rural area to “live a more simple life” with “less stuff to do, less stuff to have, less noise, less disruptions.”

Karen’s Life Narrative

Karen, 58, works in accounting and lives in a heritage-style Sydney home with her partner and two miniature schnauzers. She was born in central England where her father worked as a coal miner and her mother a homemaker for her and her five siblings. Karen’s family moved between England and Australia several times during her childhood, impacting her school life: “I was constantly going to different schools and that’s very hard for a shy child.”

After finishing high school and transitioning into young adulthood, Karen lived and worked in various places across Australia and New Zealand. She developed several hobbies: “I used to sew […] I used to knit […] I used to go to tech to learn wedding cake making and decorating […] I really loved doing that.” Karen has kept her love for creating over the years however changes in her lifestyle have limited her ability to do so: “I had more time I think […] my job wasn’t as stressful. My life’s different now. I do miss it.” In more recent years, Karen’s two pet dogs have become a central part of her life. In the future, Karen hopes to move to a small city off the south coast of Australia with her partner and two dogs to lead a more relaxed lifestyle.

Phase 2: Creation

The following section details the inspirational stories and design decisions that culminated in the artefacts created for each participant.

Alex’s Artefact: Globe

Alex’s life-long love of travel led us to consider ways we could bring about positive memories of various experiences through interactions with an object. We set out to design a world clock, providing links to other places around the world. This process resulted in Globe (see Figure 2) a 24-hour clock that displayed a city that was currently enjoying happy hour (five o’clock to six o’clock in the evening), shifting to a city in the next time zone each hour.

Figure 2. Globe: a world clock.

Many of the cities included in the clock contain their own unique associations related to Alex’s past-self, either as an individual through his solo travels or more recently through shared experiences with his daughter: “when [she] finished school […] she and I went off by ourselves to the Middle East and Italy” and his partner: “it was freezing cold when we were in Moscow.” We also included several remote cities that may have not yet been visited by Alex to create potential associations to his future anticipations for further travels to new destinations.

The unique set of experiences related to each of these cities led us to conceal time zones while outside of the happy hour period, allowing greater focus to be given to each city in isolation. The intended effect was to create moments of unexpected reflection as the clock is read at various times throughout the day, each time showing a different city in which people are finishing work for the day.

Alex’s Artefact: Kiruna

Alex’s valued possessions reflected his love for objects of art as he described his appreciation for the craftsmanship involved and the stories they often reflect. We set out to create a sculptural object that drew inspiration from his personal stories to reflect his affiliations to both delicate materiality and narrative. This process resulted in the creation of Kiruna, a porcelain decanter (see Figure 3). Porcelain was used for its associations as a precious material: “you have to look after it, if you drop it and break it, it’s very hard to repair it”, which contributes to Alex’s appreciation of sculptural artefacts.

Figure 3. Kiruna: a decanter.

In determining the form of the decanter, we drew inspiration from Alex’s description of himself as “much more a winter person than a summer person” and the significant experience of when he “mastered skiing for the first time, when I made it down an American mountain without falling down”. Skiing has also been an activity Alex shares with his children: “the kids took it up when they were two and three”, creating rich ties to family, places and experiences. Kiruna draws inspiration from the imagery of snowy mountains beneath a clear blue sky. Indentations were made in the body of the decanter to reflect the snow tracks created through the act of skiing back and forth down a mountain.

Louise’s Artefact: Diramu

Louise’s rich experiences of growing up in rural Australia “surrounded by bush” were a central theme of the stories she shared. Australian native bushlands reflect both her past identity and anticipated future identity beyond retirement as she looks forward to one day returning to a “more simple” rural lifestyle. We drew inspiration from her rich recount of bushfires approaching her family home before being doused by her parents and the local fire department: “I have these really vivid memories of trees, full trees, being on fire.” This imagery was used in the design process of Diramu, a scented candle with a transparent cover sleeve (see Figure 4). We used a smoky, campfire scented candle in conjunction with silhouettes of native Australian trees to create a sensorial experience of a flickering light and scent reminiscent of Louise’s vivid childhood memories. A candle was used for the calming effects of its gentle scent and soft lighting, pairing back the intensity of the bushfire imagery and reflecting Louise’s future anticipations of leading a less stressful lifestyle amongst bushlands.

Figure 4. Diramu: a candle cover.

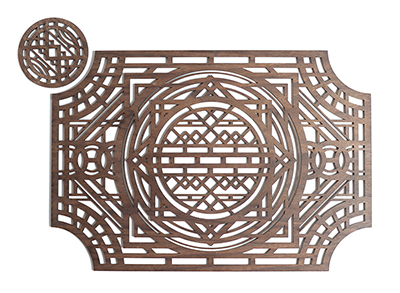

Louise’s Artefact: Geo

Louise’s role as a mother of two young boys played a definitive part in the recent stages of her life narrative, providing a source of joy through their shared experiences. We found inspiration in her and her youngest son’s shared appreciation of patterns: “he’s right into geometric tessellations and he’s really mathematical and so he loves all that and I’ve kind of grown to love that as well.” Louise also had a personal appreciation for various styles of textiles, patterns and textures including intricate paisley and floral design, the art deco era and the grain of the wood.

In our design process, we set out to create a set of placemats and coasters to be used during family dinners that reflected Louise’s youngest son’s love of geometry and her own personal attraction to the art deco aesthetic. The resulting design Geo (see Figure 5) drew inspiration from the art deco movement to create intricate, geometric shapes cut from stained wooden sheets to reflect Louise’s identity as a mother and as an individual.

Figure 5. Geo: a set of placemats and coasters.

Karen’s Artefact: Crater

Karen’s relationship with her father as a child was a source of some of her fondest memories: “very alike my dad and […] I miss him.” We drew inspiration from her vivid recount of daily routines: “I always remember my dad coming home from one of his shifts with his black coal face” and the experiences they shared: “Dad would always collect me from school and I always remember his big hand holding my hand.”

In our process, we sought ways of using the imagery of coal to bring about positive memories of Karen’s father, resulting in Crater (see Figure 6). We were cautious to avoid the common associations of coal as dirty and instead aimed to treat the material as precious, using a piece of anthracite coal much like a gemstone. We saw the coupling of coal with worn jewellery as an ideal way of reflecting the significance and closeness of Karen’s relationship with her father. The coal piece also invited further engagement through its tactility, containing smoothed edges that fit within a person’s hand.

Figure 6. Crater: a pendant necklace.

Karen’s Artefact: Dyad

Karen’s love for her partner and two dogs were ties we tried to draw upon in our design process. In our interview, Karen vividly described the distinct personalities of each of her dogs: “He’s very loving, very affectionate, he’s cheeky, […] she’s reserved, she’s serious.” In a similar way, Karen described herself and her partner as opposites and likened her reserved dog to her partner. We tried to reflect the opposing yet harmonious personalities of Karen and her partner and her two dogs in the design of Dyad, a set of indoor pot plants with character-like features (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Dyad: a set of pot plants.

In our process of creating Dyad, we drew inspiration from Karen’s love of creating, particularly her history of knitting and sewing. We adopted a technique of needle felting wool roving to convey distinct personalities between the two pots. Grey wool was used to suggest a sombre tone and her partner’s preference for an industrial aesthetic of stainless steel, while a mixture of vibrant red and orange hues reflected Karen’s personal affiliations: “I was born in autumn so I like all those [colours].”

Phase 3: Evaluation

In this section, we discuss the associations that participants assigned to their self-selected cherished possessions and the designed artefacts. There was a possibility that participants’ knowledge of the study may influence the associations they assigned to our designed artefacts by recalling the stories they shared with us and identifying our design intentions. We questioned participants at the end of their involvement in the study and found this not to be the case in any instances.

For both the cherished possessions and the introduced artefacts, participants described associations to significant people, places, experiences, time periods, events and emotions. When asked to elaborate on these associations, it became clear that they ranged from signifiers of specific events to providing vague feelings that were at times difficult to describe.

Alex’s Associations

Alex’s selected cherished possessions were his teddy bear, a Russian hat and a framed oil painting of an Australian landscape (see Figure 8). Each of these items possessed a rich shared history of ownership with associations to significant people, memorable experiences and fond time periods in his life. Associations reported by Alex also linked to broader ideas such as legacy, security and new life, providing insights into the ways in which these belongings are appropriated as part of creating a coherent life narrative and robust sense of self.

Figure 8. Alex’s cherished possessions: teddy bear, Russian hat and oil painting.

Alex’s experiences and responses to the designed artefacts were varied. The porcelain decanter Kiruna, which was deliberately designed for him, was associated with positive aesthetics, being considered elegant and attractive as it tied in with his personal appreciation for artistic objects: “I’m a ceramics person.” Alex did not form associations relating to his love for skiing or winter activities, instead seeing parallels in the colours to Greece and going on to question its practicality as a decanter.

The world clock Globe was also designed specifically for Alex and was associated with many of his travel experiences: “it reminded me of memories of Timbuktu, Florence, Moscow, Dubai, Tashkent….”, however, it was ultimately viewed in a negative light. This could be attributed to a multitude of reasons. The clock itself was found to cease functioning for the two-week period in which it stayed in Alex’s home, nullifying the intended experience of use. Globe was also developed as much more a prototype than a finished product when compared to the other designed artefacts and his own cherished items, potentially lowering its perceived aesthetic quality and value. While Globe was successful in forming associations with Alex’s rich history of travel experiences as we intended, it did not gain meaning in doing so: “I have wonderful memories of about three quarters of those cities but that thing doesn’t reflect those.” This raises the issue of authenticity in designing objects with meaningful associations in which the overall perceptions of the object may not align with those ascribed by the user to the associated source.

Alex was also given the candle cover Diramu, which, while not intended for him, evoked fond memories of his experiences of North American forests: “my first trip to America was in the middle of winter […] the sun set early so the night-time, which the candle sort of implies, is half my memories of that initial trip.” While Alex recognised the Australian bushfire motif, he had no personal connection to it. Instead, his perceptions were shaped by his associations with the product category of candles, both geographic: “Candlelight in my mind is a very North American, northern hemisphere should I say type of light” and temporal in nature: “the only time I ever seem to have candles in the house is Christmas, so it reminds me of Christmas.”

The product categories that Alex perceived each of the designed artefacts to fit within played an integral part in the way they were perceived. Alex’s established views of ceramics as often elegant, souvenir shop items as useless and candlelight as northern intertwined with the memories each item brought to mind. These associations either reinforced or undermined one another, influencing the overall strength of the links.

Louise’s Associations

Louise included a pair of ruby earrings, a Moorcroft vase and a small silver hedgehog figurine as some of her most cherished items (see Figure 9). Each item contained a number of rich stories with links to significant people, places, emotions and events. Associations reported by Louise would encompass a broad picture of her experiences including both the good (beautiful, carefree, love) and bad (noise, smelly, death).

Figure 9. Louise’s cherished possessions: ruby earrings, Moorcroft vase and silver hedgehog.

Louise’s interactions with the designed artefacts similarly reminded her of significant people, places, events and time periods. The set of placemats and coasters Geo, specifically designed for her, reminded her most strongly of her two children for varying reasons: “[eldest son] loves woodwork and [youngest son] loves geometric designs.” The intricate patterns were associated with folk art from Latvia, her husband’s country of birth. While we gained inspiration in the design process from Louise’s youngest son’s interest in complex geometry and were successful in reflecting this in our design, we were not able to predict the additional family ties it would elicit. These strong associations ultimately represented a broader view of the family’s future based on the development of their current identities: “these were more about possibilities and what the kids might do in the future and the things that they’re interested in.”

Louise’s interactions with the candle cover Diramu, also specifically designed for her, evoked vivid childhood memories of the night her family home was saved from a nearby bushfire. When lit, the candle “brought back these amazing memories” as the visual effect it created “looked like the night” and the smell it released “was like the burning of eucalyptus”. Louise’s encounter with a bushfire as a child could have potentially been a negative or even traumatic memory. Its role in our design relied on our interpretations of the way in which Louise discussed the memory in our interviews. She explained that the experience the candle evoked for her “wasn’t a scary feeling at all”, instead it was “like being in […] a pleasant bushfire, not an unpleasant bushfire.” Beyond this vivid association to a childhood memory, Louise recounted the ill-defined thoughts it brought to mind: “the smell of it had a certain… I don’t know… feeling of home.”

Our design intentions were successful in evoking Louise’s vivid childhood memory of bushfire in a calming and pleasant manner. When asked to rate and discuss the candle’s value to her, Louise described it as quite emotive and very meaningful because of its rich personal associations: “it tapped in to something that was […] a really strong memory for me.” The effectiveness of Diramu may be due to its specific and somewhat literal representation of an aspect of Louise’s life narrative, providing a definitive link as opposed to the more abstract representation utilised in other designs.

The decanter Kiruna, not designed for Louise, was the third artefact given to her and of the three, the one she associated with least. The form of the porcelain decanter was likened to frozen water. This imagery supported Louise’s interpretation of it to be cold and aloof in character: “it felt like it didn’t want to be interacted with.” Despite describing the piece as beautiful, the associations it brought to mind for Louise were contradictory to her own sense of self: “we’re kind of messy wood people so it wasn’t something I felt an affinity with.” While Louise found the decanter to reflect imagery similar to our intended snowy mountain, she had no personal connection to this imagery.

Karen’s Associations

Karen’s relationship with objects in general was distinctly different to our other participants. In our initial interview, she described herself as someone who does not assign sentimental value to her possessions. After further discussion, she was able to identify three possessions that she cherished: her car, a sewing machine and the house she lived in (see Figure 10). Karen’s car and sewing machine were not associated with any specific memories, but rather positive feelings such as enjoyment, safety and comfort that came about through their use. The house Karen lived in had a more extensive group of associations, linking to her partner, her dogs, the feeling of coming home and a rich history of her life in recent years.

Figure 10. Karen’s cherished possessions: her car and her house.

Karen’s initial reaction on being given the first item designed for her, the necklace Crater, was that it reminded her of her father. Although she responded positively to the necklace: “it’s quite nice, I quite like it”, it did not hold any significance to her: “I didn’t grow any attachment to it.” This acts as another instance in which our design successfully evoked an intended association for the user but the emotional significance of the source, Karen’s relationship with her father was not transferred to the object. This highlights a key challenge to designing objects with meaningful associations in which the designed artefacts do not have an extensive shared history with the owner. This lack of history may discredit the authenticity of the association in the eyes of the owner, as the object cues, but does not embody a significant part of their identity.

Karen was also given the set of pot plants Dyad, designed for her and the set of placemats and coasters Geo (not designed for her). While Geo was positively received—“I just loved them. I used them every day”—neither of the two sets of artefacts evoked significant associations for Karen during the two-week period. Although this was an ineffective result for the design of Dyad, Karen provided greater insight into her connection to objects by using the dining table we sat at during the interview as an example:

I’ve had this table a very long time. I’ve had lots and lots of good dinner parties […] this could tell a thousand stories […] but I’m not attached to it […] I can let it go tomorrow. If you wanted this tonight, I’d say take it. It doesn’t mean much to me.

Reflecting on the transcript of our initial interview, it became clear that Karen would rarely assign meaning to an object but rather engaged in several meaningful practices throughout her life. She fondly recalled her love for cooking, cleaning, sewing, knitting, baking and decorating that extended from her youth to adulthood: “I loved the process […] I just loved doing it.” While Dyad gained inspiration from Karen’s love for knitting, it did not reflect the process, but rather the resulting outcome, which often held little emotional value.

We see this variation in the ways in which people engage with their belongings as a signifier of product attachment as a construct that fits within a broader context of meaning making that occurs through people’s ongoing relationships to places, people, practices, experiences or things.

Discussion

We set out to apply product attachment theory to our design practice to better understand the ways in which design can support users in engaging in a process of meaning making and identity construction through their relationships with products. In doing so, we entered a dialogue with our participants in which they provided inspiration for and responses to a range of designs intended to reflect aspects of their identity and life narrative. The experiences of our participants while engaging with our artefacts highlight the various ways in which people evaluate objects through their inferred associations. In this section, we reflect on our design process and resulting artefacts to highlight key opportunities and considerations for designing objects with meaningful associations.

Opportunities and Considerations in Designing for Product Attachment

Our process of incorporating significant memories and associations within a designed product contains several promising aspects for promoting product attachment. Firstly, the active inclusion of meaningful associations brings emotional value to the object in the initial stages of ownership, much like the value often assigned to a family heirloom or thoughtful gift upon receipt. This contrasts with existing design strategies that rely on attachment to develop over an extended period of time through everyday interactions (Mugge et al., 2005). Secondly, the degree of attachment established from meaningful memories and associations is often argued to be greater than other determinants of attachment (Niinimäki & Koskinen, 2011; Page, 2014; Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008), leading to a stronger emotional bond between the product and user.

Although our artefacts and process were effective in many ways, there are also several limitations to what we as designers can achieve in promoting meaningful user-object relationships. A person’s need for self-expression is finite (Chernev, Hamilton, & Gal, 2011), there being a limit to the number of possessions an individual will use to represent their individuality. This may hinder the integration of new products into their established sense of self. In addition to this, designers cannot design an emotional experience, they can only design for an emotional experience as emotions are ephemeral and dependant on context (Hassenzahl, 2004). Designers are therefore limited to creating possibilities instead of certainties in any attempt to design for product attachment.

The approach outlined in this paper also contains further limitations to its application in practice. To elicit a desired associative response, designers are faced with the difficult task of anticipating another person’s reaction to the products they create. This requires an empathic approach to understanding a user’s needs, values and beliefs. Our artefacts were also designed for a single individual with inspiration derived from their unique life stories, an approach that is often not possible in traditional design practice. This limitation is partly inherent to the way in which people form attachments to their belongings. Previous studies have highlighted that the experience of attachment is unique to the individual (Niinimäki & Koskinen, 2011) and that it is not possible for one design to have emotional value for all intended users (Desmet et al., 2001). Nevertheless, we see potential for meaningful associations and an empathic approach to be utilised in several scenarios such as designing for specific cultural groups as they often form similar inferences about a product (Allen, 2006) or designing personalised jewellery (e.g., wedding rings). Advancements in custom manufacturing technology such as 3D printing provide growing opportunities for bespoke design practices such as those presented in this paper as an alternative to traditional mass production processes.

Reflecting on our Design Process

Much like our own study, designers often make use of characters and narrative data within their ideation processes to guide design decisions and encourage alternate viewpoints, most commonly seen in the use of personas (Cooper, 1999). These personas and other similar methods risk providing an over-simplified view of users by generalising and summarising information prior to the ideation phase of the design process (Golsteijn & Wright, 2013). In our approach, we saw merit in using in-depth research methods to gain a greater depth of understanding of the complexities and nuances of real life contexts that design practices work within (Wrigley, Gomez, & Popovic, 2010). Our interviews were successful in providing sufficiently rich data to use as inspiration for our bespoke designs. We found our participants’ detailed stories of specific experiences were particularly useful for generating concepts, providing us with vivid yet focused design directions. Although our implementation of semi-structured interviews may have limited the amount of storied responses we received (Golsteijn & Wright, 2013), we found this approach crucial to understanding the different ways in which our participants perceived underlying aesthetic elements of objects such as material, colour and form.

We saw value in continuing our in-depth approach in the development and evaluation of our bespoke designs. In doing so, we endeavoured to create artefacts that were closer to finished products than conceptual prototypes, allowing our participants to engage with them in the same way they would their own household belongings. We focused predominantly on the imagery and materiality of the object to reflect the life stories of our participants, resulting in designs that were more decorative than functional. This was partly due to production constraints involved in creating one-off designs but also part of our attempt to create simple designs that limit the amount of possible associations that were beyond our understanding of the individuals we were designing for. The potential value of using the functionality or interactivity of objects to facilitate meaningful associations remains an unexplored area for future work. Additionally, the growing presence of digital components within products brings new challenges to designers seeking to promote attachment (Kirk & Sellen, 2010). Further exploration of the value of meaningful associations within the digital realm would provide insights relevant to the shifting nature of product design practices.

In our evaluation of the emotional significance of a range of designed artefacts, we adopt the argument that attachment is definitively linked to the self. This led us to focus our attention on the associations assigned to various objects to determine whether they were generic or personal in nature, asking participants to elaborate on the thoughts that come to mind to understand whether these links brought meaning to them. The six bespoke artefacts that resulted from our process received mixed reactions from our participants. In most instances, we were successful in creating intentional associations between an object and a personal idea. Some artefacts were even able to cue specific memories and experiences. We are reluctant to make any claims of the meaning ascribed by participants to any of our designs due to the small sample of artefacts involved, the short time frame of the experiment and the subjectivity of participant responses. Our most notable example of an object that may hold genuine meaning would be in Louise’s response to Diramu in which she described it as quite emotive and very meaningful for its links to her childhood. From this, we see our artefacts as examples of the potential for design to tap into user’s internal processes of meaning making or identity construction and our design process as an effective way to guide the ideation and development of bespoke products.

Creating Meaning

In our study, we set out to create objects that tapped into meaningful imagery already in the minds of our participants. In doing so, we intended to facilitate the formation of emotional value in an artefact through its ability to characterise and communicate significant memories, experiences and values held by the user. Our six designed artefacts reflect mixed results in achieving these goals. We use these mixed results to propose two conditions that are required in designing objects with meaningful associations: cueing meaning and authentic embodiment.

Cueing Meaning

Some of our artefacts reflected an aspect of a participant’s sense of self but were not deemed overly significant in doing so (see Kiruna). This issue relates to the identity salience, that is, “the relative importance of a given identity in an individual’s self-structure” (Kleine, Kleine, & Kernan, 1993, p. 223) that is associated with the object. What a person considers to be a meaningful aspect of their identity is continually changing throughout their lifetime as their sense of self develops (Kleine et al., 1995). To hold meaning for an individual, an object must cue aspects of their identity that are considered meaningful, whether it be their personal values, relationships with others, past experiences, or hopes for the future.

Although the notion of cueing meaning is simple in theory, it is difficult to achieve in practice. The porcelain decanter Kiruna held ties to Alex’s self-view as a ceramics person, yet this aspect of his identity was not in itself significant enough to bring meaning to the object. Designers must employ an empathic approach to understand the relative importance of an individual’s experiences, values, beliefs, or relationships. An example of this empathic approach can be seen in our decision to use Louise’s recollection of a pleasant bushfire as the primary source of inspiration for the candle cover Diramu despite bushfires usually being perceived in a negative light. The results of our study suggest that cueing memories of specific experiences was more meaningful than reflecting a general time period, value or belief. We found the specificity of these events allowed for more engaging design representations. These cued memories of an event (e.g., a bushfire) were also found to trigger associations to a broader context within a person’s life narrative (e.g., childhood, summer and home), however, associations to a broad concept (e.g., family) did not trigger memories of specific experiences.

Authentic Embodiment

Some of our artefacts cued, but did not represent, a significant aspect of a participant’s self-identity (see Globe and Crater). Despite evoking associations to an emotionally significant source (e.g., Alex’s travel experiences), the meaning of this source was not transferred to the object. Creating objects with meaningful associations requires the user to perceive the associations as authentic, that is, they must perceive the object to successfully embody the associated source. Our design for the world clock Globe cued memories of Alex’s travel experiences but was also likened to common souvenirs, relating to a style of travel that Alex actively avoids and thus detracting from the authenticity of the embodiment. This issue of authenticity can be likened to the concept of identity relevance (Reed et al., 2012) in which a product symbolises a belief, goal, value or identity. Symbolic meaning often develops from the proximity of the object to the source of meaning (Belk, 1988) such as a kitchen knife used to prepare meals shared with friends and family or a pair of gloves worn while gardening. Our findings suggest authentic embodiments can also be created by tapping into the meaningful imagery already in the minds of intended users (see Geo and Diramu). To create associations that are perceived to be authentic, designers must consider an intended user’s pre-constructed understandings of product categories and features such as the materiality of the object, the product experience and beliefs of the kind of person who would use or own such an object.

Conclusion

Product attachment theory suggests that people develop an attachment to an object for its role in the construction, maintenance or development of an aspect of their self-identity. These objects are often assigned emotional value for their associations to memories, experiences, values, aspirations, people or places. We set out to explore the potential for design to promote the formation of product attachment by developing a process of designing objects with meaningful associations, using the life stories of our intended users as inspiration for the creation of several artefacts. Our evaluation of these artefacts reflected mixed results that highlight the need for designers to consider both the importance of an associated aspect of identity and the authenticity of the embodiment itself to create objects that hold meaning for an individual. We intend for the process and resulting artefacts presented in this paper to inspire designers to further explore the value of meaningful associations in their practice to enrich user-product relationships.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants for their time and contributions. This study was approved by the UTS Ethics Committee (#2015000629) and supported by STW VIDI grant number 016.128.303 of The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), awarded to Elise van den Hoven and an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship awarded to Daniel Orth.

References

- Ahuvia, A. C. (2005). Beyond the extended self: Loved objects and consumers’ identity narratives. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(1), 171-184.

- Allen, M. W. (2002). Human values and product symbolism: Do consumers form product preference by comparing the human values symbolized by a product to the human values that they endorse? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(12), 2475-2501.

- Allen, M. W. (2006). A dual-process model of the influence of human values on consumer choice. Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho, 6(1), 15-49.

- Ball, A. D., & Tasaki, L. H. (1992). The role and measurement of attachment in consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 1(2), 155-172.

- Battarbee, K., & Mattelmäki, T. (2004). Meaningful product relationships. In D. McDonagh, P. Hekkert, J. van Erp, & D. Gyi (Eds.), Design and emotion: The experience of everyday things (pp. 337-344). London, UK: Taylor & Francis.

- Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139-168.

- Chapman, J. (2009). Design for (emotional) durability. Design Issues, 25(4), 29-35.

- Chernev, A., Hamilton, R., & Gal, D. (2011). Competing for consumer identity: Limits to self-expression and the perils of lifestyle branding. Journal of Marketing, 75(3), 66-82.

- Cooper, A. (1999). The inmates are running the asylum: Why high-tech products drive us crazy and how to restore the sanity. Indianapolis, IN: Sams Publishing.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Rochberg-Halton, E. (1981). The meaning of things: Domestic symbols and the self. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Da Silva, O., Crilly, N., & Hekkert, P. (2015). How people’s appreciation of products is affected by their knowledge of the designers’ intentions. International Journal of Design, 9(2), 21-33.

- Deaux, K., Reid, A., Mizrahi, K., & Ethier, K. A. (1995). Parameters of social identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(2), 280-291.

- Desmet, P. (2003). Measuring emotion: Development and application of an instrument to measure emotional responses to products. In M. A. Blythe, A. F. Monk, K. Overbeeke, & P. C. Wright (Eds.), Funology: From usability to enjoyment (pp. 111-123). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Desmet, P. M. A., Overbeeke, K., & Tax, S. (2001). Designing products with added emotional value: Development and application of an approach for research through design. The Design Journal, 4(1), 32-47.

- Fazio, R. H. (2007). Attitudes as object-evaluation associations of varying strength. Social Cognition, 25(5), 603-637.

- Frayling, C. (1993). Research in art and design. Royal College of Art Research Papers, 1(1), 1-5.

- Golsteijn, C., & Wright, S. (2013). Using narrative research and portraiture to inform design research. In Proceedings of the IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 298-315). Heidelberg, Berlin: Springer.

- Govers, P. C. M., & Mugge, R. (2004). ‘I love my Jeep, because it’s tough like me’: The effect of product-personality congruence on product attachment. Retrieved from http://www.pascallegovers.nl/uploads/1/2/3/9/12391484/govers_and_mugge_de2004.pdf

- Greenwald, A. G. (1988). A social-cognitive account of the self’s development. In D. K. Lapsley & F. C. Power (Eds.), Self, ego, and identity: Integrative approaches (pp. 30-42). New York, NY: Springer.

- Hassenzahl, M. (2004). Emotions can be quite ephemeral; we cannot design them. Interactions, 11(5), 46-48.

- Hekkert, P., & Cila, N. (2015). Handle with care! Why and how designers make use of product metaphors. Design Studies, 40, 196-217.

- Kirk, D. S., & Sellen, A. (2010). On human remains: Values and practice in the home archiving of cherished objects. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 17(3), 1-43.

- Kleine, S. S., & Baker, S. M. (2004). An integrative review of material possession attachment. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 1, 1-35.

- Kleine, S. S., Kleine, R. E., & Allen, C. T. (1995). How is a possession “me” or “not me”? Characterizing types and an antecedent of material possession attachment. Journal of Consumer Research, 22(3), 327-343.

- Kleine, R. E., Kleine, S. S., & Kernan, J. B. (1993). Mundane consumption and the self: A social-identity perspective. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2(3), 209-235.

- Kujala, S., & Nurkka, P. (2012). Sentence completion for evaluating symbolic meaning. International Journal of Design, 6(3), 15-25.

- Lacey, E. (2009). Contemporary ceramic design for meaningful interaction and emotional durability: A case study. International Journal of Design, 3(2), 87-92.

- Linde, C. (1993). Life stories: The creation of coherence. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- McAdams, D. P. (1985). Power, intimacy, and the life story. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press.

- Mugge, R., Schifferstein, H. N., & Schoormans, J. P. (2005). A longitudinal study of product attachment and its determinants. In K. M. Ekström & H. Brembeck (Eds.), European advances in consumer research volume 7 (pp. 641-647). Duluth, MN: Association for Consumer Research.

- Mugge, R., Schoormans, K. P., & Schifferstein, H. N. (2005). Design strategies to postpone consumers’ product replacement: The value of a strong person-product relationship. The Design Journal, 8(2), 38-48.

- Mugge, R., Schoormans, K. P., & Schifferstein, H. N. (2008). Product attachment: Design strategies to stimulate the emotional bonding to products. In H. N. Schifferstein & P. Hekkert (Eds.), Product experience (pp. 425-440). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier.

- Mugge, R., Schoormans, K. P., & Schifferstein, H. N. (2009). Emotional bonding with personalised products. Journal of Engineering Design, 20(5), 467-476.

- Myers, E. (1985). Phenomenological analysis of the importance of special possessions: An exploratory study. Advances in Consumer Research, 12(1), 560-565.

- Niinimäki, K., & Koskinen, I. (2011). I love this dress, it makes me feel beautiful! Empathic knowledge in sustainable design. The Design Journal, 14(2), 165-186.

- Norman, D. (2004). Emotional design: Why we love (or hate) everyday things. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Orth, D., & van den Hoven, E. (2016). “I wouldn’t choose that key ring; it’s not me”: A design study of cherished possessions and the self. In Proceedings of the 28th Australian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction (pp. 316-325). New York, NY: ACM.

- Page, T. (2014). Product attachment and replacement: Implications for sustainable design. International Journal of Sustainable Design, 2(3), 265-282.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 8(1), 5-23.

- Reed, A., Forehand, M. R., Puntoni, S., & Warlop, L. (2012). Identity-based consumer behavior. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(4), 310-321.

- Schifferstein, H. N. J., & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, E. P. H. (2008). Consumer-product attachment: Measurement and design implications. International Journal of Design, 2(3), 1-13.

- Schultz, S. E., Kleine, R. E., & Kernan, J. B. (1989). “These are a few of my favorite things”: Toward an explication of attachment as a consumer behavior construct. Advances in Consumer Research, 16(1), 359-366.

- Thomson, M., MacInnis, D. J., & Park, C. W. (2005). The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(1), 77-91.

- Van Krieken, B., Desmet, P. M. A., Aliakseyeu, D., & Mason, J. (2012). A sneaky kettle: Emotionally durable design explored in practice. Retrieved from http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:a6613b2b-6377-409b-a17d-5fac98871905

- Wallendorf, M., & Arnould, E. J. (1988). “My favorite things”: A cross-cultural inquiry into object attachment, possessiveness, and social linkage. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(4), 531-547.

- Wrigley, C., Gomez, R. E., & Popovic, V. (2010). The evaluation of qualitative methods selection in the field of design and emotion. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/39855/1/c39855.pdf

- Zimmerman, J. (2009). Designing for the self: Making products that help people become the person they desire to be. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 395-404). New York, NY: ACM.