Exploring Types and Characteristics of Product Forms

Wen-chih Chang 1, Tyan-Yu Wu 2,*

1 Graduate School of Design, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taipei, Taiwan

2 Department of Industrial Design, Chang Gung University, Tao-Yuan, Taiwan

*Corresponding Author: tnyuwu@mail.cgu.edu.tw

Incorporating emotional value into products has become an essential strategy for increasing a product’s competitive edge in the consumer market. It is therefore important for product manufacturers to understand how products affect consumers’ emotions. This study was undertaken to investigate the types and characteristics of household products that elicit pleasurable responses, in particular among young, college-age consumers. The results of the study could suggest the types and characteristics to consider when developing pleasurable products aimed at young consumers.

In-depth interviews were conducted with 30 participants in order to collect responses that showed evidence of pleasurable feelings. From 262 initial images chosen, 19 were extracted as stimuli for the interviews. Data analysis was used to group key sentences obtained in the responses. The results produced 14 characteristics that could be categorized into five types of pleasurable forms: Aesthetic, Bios, Cultural, Novelty and Ideo. Among the responses of the interviewees, those related to Aesthetic and Bios forms were mentioned most frequently and thus, these forms were found to be the ones most likely to elicit consumer pleasure. Moreover, it was found that the responses to hi-tech products tended to highlight characteristics related to the Aesthetic type of pleasurable form, and the responses to kitchen products to the Bios Form.

Keywords - Emotion, Pleasurable Products, Product Forms, Cluster Analysis.

Relevance to Design Practice - Five types of pleasurable forms and 14 associated characteristics are identified and discussed in this study. By understanding each type of pleasurable form and its characteristics, designers can apply this information to designing pleasurable consumer products, particularly ones aimed towards the young, college-age market.

Citation: Chang, W. C., & Wu, T. Y. (2007). Exploring types and characteristics of product forms. International Journal of Design, 1(1), 3-14.

Received August 15, 2006; Accepted January 17, 2007; Published March 30, 2007

Copyright - © 2007 Chang and Wu. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 Lincense. By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

Dr. Wen-chih Chang earned his master’s degree in Industrial Design at Syracuse University in New York in 1980. Since then, he has been an industrial design teacher and product designer. In 1993, he received his doctorate in Design Management from Manchester Metropolitan University in the U.K. Being a design consultant for many companies and for many years has given him a deeper understanding of design practice in the business world. He specializes in the research of product design management (e.g., design strategy, design quality, organizational creativity and product design performance) and the relationship between product image and product form features.

Since 1997, Tyan-Yu Wu has been teaching Industrial Design at Chang Gung University. Before embarking on his teaching career, he worked with Kemnitzer Design, Blue Leaf Design, and Tatung Telecom in the United States as an industrial designer. He graduated in 1991 from the University of Bridgeport with a BS degree and earned his master’s degree from San Jose State University in the USA in 1994. He was a member of IDSA in 1992 and has been a member of both CIDA and CID since 2000. Currently, he is studying for his Ph.D. at National Taiwan University of Science and Technology. His areas of research interest are pleasurable product design and Taiwanese aboriginal culture in product design.

Introduction

Aristotle stated that more than anything else, men and women seek happiness (Csikszentmihalyi, 1992). Seligman (2005), the current President of the American Psychological Association (APA), has also claimed that, instead of studying only the ills of the human mind, as has been the case in past psychological research, we now should not neglect the role of happiness in human psychology and should be more aggressive in the study of positive emotions in order to help people pursue a happier life. In product design, Desmet and Overbeeke (2001) believed that positive emotion can add extra value to a product, while Marzano(1998) also stressed that products are objects that can make people happy or angry, proud or ashamed, secure or anxious. Jordan (1998) implied that a product with perceived pleasantness was used more regularly or purchased more frequently than one without. Cho and Lee (2005) also agreed that one of the most important considerations in modern industry is to satisfy the emotional demands of consumers with regard to products. Hence, Crossley (2003) suggested that a designer should create relevant emotional connections among ideas, products, services and brands.

Janlert and Stolterman (1997) also noticed that people and things appear to have high-level attributes that help us understand and relate to them. He illustrated, for instance, that a car designed with rounded forms and in warm colors may evoke a warm, friendly and protective character. He further suggested that it might be helpful to designers if dependencies between appearance and perceived character could be determined. This suggestion implies that it is important to find product types and characteristics that elicit pleasurable responses from consumers.

Research Aim

This research proposes to investigate types and characteristics of household products, focusing in particular on visual appearance, that is, on those qualities that evoke consumer pleasure through simply the look of the product. The purpose of focusing on the household is that, just as Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton (1981) suggests, ‘household objects’ are crucial for experiencing pleasure in the home and represent the endogenous being of the owners. These objects are the ones most involved in creating the owner’s identity and in making him or her feel happy. Furthermore, the emphasis on visual appearance was chosen because it is a critical determinant of consumer response and product success (Crilly, Moultrie, and Clarkson, 2004 & Bloch, 1995). Moreover, this paper aims to find out how different types of pleasurable forms are used in different types of household products. The results, it is hoped, will be of benefit to designers in developing pleasurable products.

However, it is necessary to clarify the difference between this research and Jordan’s in two aspects. Firstly, the present research aims to emphasize pleasure gained through visual perception only, rather than focusing on all aspects. This means that we do not consider the pleasure that is evoked through physical interaction or performance. Secondly, this paper aims to focus on the pleasure evoked through household products only, rather than on a whole range of products, as Jordan does. By focusing on the visual appearance of only household products, the results are meant to assist designers in understanding and further embedding pleasurable elements into household products, specifically when developing a product’s appearance.

The Types of Pleasure and Product Emotions

The Oxford English Dictionary defines pleasure as “the condition of consciousness or sensation by the enjoyment or anticipation of what is felt or viewed as good or desirable; enjoyment, delight, gratification” (Simpson & Weiner, 1989). Jordan (2000) stated that pleasure in relation to products can be defined as “the emotional, hedonic and practical benefits associated with products”. In this paper, a pleasurable product is defined as one that elicits consumer pleasure simply by its visual appearance. However, only a very few other studies relevant to this paper have been done at present (e.g., Seligman’s, Duncker’s, Tiger’s and Jordan’s studies). In these works, the various typologies of pleasure have been identified, as discussed in the following paragraphs.

In his research on authentic happiness, Seligman (2002) identified two levels of pleasure: bodily pleasure and higher pleasure. He posited that bodily pleasure is an immediate but temporary sensory response. Through direct touch, taste, smell, sight, or hearing, bodily pleasures can be evoked at once. For instance, taking a hot shower in the cold winter can produce immediate comfort and pleasure. Higher pleasure involves the same primitive sensation as bodily pleasure but with a more complex cognition process. It is noticed that for a product to evoke higher pleasure, it is necessary for the consumer to understand the product’s content. For instance, a listener might feel pleasure when listening to harmonic music, but can gain a higher level of pleasure if he or she understands the content of the music.

In 1941 Duncker sidestepped the body-soul dichotomy and identified three types of pleasure: sensory, aesthetic, and accomplishment pleasures. Sensory pleasure involves the immediate object of pleasure being in the form of a sensation (e.g., the flavor of wine, the feel of a hot shower); aesthetic pleasure involves sensation that is an expressive response to something, whether offered by nature or created by man (e.g., a beautiful mountain, harmonious music); accomplishment pleasure represents the pleasant emotional consciousness that something valued has come about (e.g., mastery of a skill, an impressive sports performance) (Dubá & Le Bel, 2003). Among these three types of pleasure, sensory pleasure and aesthetic pleasure can be associated with the physical and spiritual pleasure experienced in relation to the visual appearance of a product, and this is the focus of this paper. Accomplishment pleasure, on the other hand, deals with the assessment of personal skill, performance and goals, and is thus difficult to evaluate when it comes to just looking at a product; this level of pleasure, therefore, is not covered in this study.

Both Seligman’s and Duncker’s typologies distinguish pleasure at two levels: the physical-sensation and the mind-thought level. According to this categorization, a consumer may derive pleasure from perceiving a product’s appearance and its embodied meaning. In other words, the consumer may feel pleasure on perceiving a product with an interesting appearance, and furthermore may also experience another level of pleasure on understanding the context of the product’s appearance. The entire process involves a consumer’s perceptions towards explicit and implicit product information. Hence, to understand customer pleasure it is necessary to discover what information consumers perceive from product appearance and its concealed meaning; for this reason, the responses of consumers provided the basic material used for identifying characteristics and types of product form in the data analysis of this study.

In his research, Tiger (1992) identified four types of pleasure: physio-pleasure, socio-pleasure, psycho-pleasure, and ideo-pleasure. These were identified by studying recovered archaeological records, and the evolution theories of genetics and physiology. Physio-pleasure can refer to the physical sensation obtained from eating or drinking. Socio-pleasure can refer to the enjoyment derived from relationships with others. Psycho-pleasure can refer to the satisfaction enjoyed as a result of individually motivated tasks or acts. And ideo-pleasure can refer to ideas, images, and emotions that are privately experienced. Using Tiger’s theory as a basis, Jordan further classified pleasurable products into four categories. The first category contains products that evoke physio-pleasure, for example, through the feeling of touching the product. The second contains products that provide socio-pleasure. In this category are products that can facilitate social interaction, for example by helping one to chat with friends. The third category is psycho-pleasure. In terms of products, this type of pleasure relates to the cognitive demands and the emotional reactions engendered through experiencing the product. The fourth category is ideo-pleasure, which here relates to people’s values. For example, a product made from biodegradable materials may convey ideo-pleasure to those who are particularly concerned about environmental issues (Jordan, 2000).

Compared with Seligman’s and Duncker’s, Tiger’s typology illustrates a broader range of classifications for pleasure. His emphasis is not only on physical and cognitive pleasure, but also on the value of social interaction. According to this thinking, consumers can appreciate the beauty of a product because it elicits pleasure, and can also share that pleasure with friends. His approach is useful for extending such categories to the study of pleasurable products as has been done by Jordan.

Methods

This study made use of in-depth interviews for the purpose of collecting pleasurable responses (raw data) from 30 participants, and it employed the induction approach in the development of data analysis. Data analysis was used for organizing the raw data into a hierarchical list and, further, for identifying types and characteristics of pleasurable products. The detailed process is described in the following section.

Stimulus Selection

The stimuli chosen for the interviews focused on three types of household objects: kitchen products, hi-tech products and household appliances. The category of hi-tech appliances (e.g., computer screens and computer mice) pertains to products using digital technology, kitchen products (e.g., plates and other tableware) to products used for serving food, and household appliances (e.g., TVs, stereos, radios) to other products used in the home. There are two reasons for selecting the above three categories. The first is that hi-tech products are very commonly used in the home environment. Secondly, household appliances and kitchen products were mentioned most frequently by interviewees in Csikszentmihalyi’s research on cherished household possessions (Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton, 1981). However, furniture items (e.g., chairs, tables, beds) were ignored in this research because the pleasure evoked from furniture sometimes relies more on physical, ergonomic satisfaction, which is not the focus of this research.

Two hundred and sixty-two images were collected from three major international competition catalogues and from catalogues published by large companies. The breakdown of image sources was as follows: 27 images from ‘iF’ (2002), 56 from ‘IDEA’ (2002), 63 from ‘G-Mark’ (2002), and 116 images from company catalogues of IBM, Philips, Alessi, and Apple. These images were outputted on 3x5-inch photo paper.

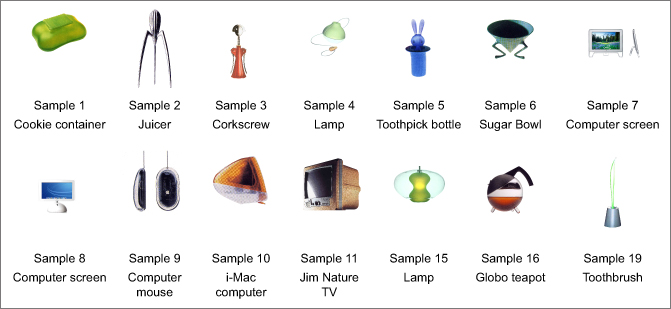

A group of 12 designers working at various companies at senior designer or product manager level were then selected to preview these 262 images. The reason for inviting professional designers to select samples from the images was that they tend to have more experience with and be more sensitive to product-related emotion, which covers a broad range of consumer pleasure responses. Before beginning the selection process, the Oxford English Dictionary definition of ‘pleasure’ and the definition of ‘a pleasurable product’ as discussed in the introduction of this paper were explained to the 12 designers. They were then instructed to identify pleasure elicited through the visual appearance of products only and to ignore any pleasure elicited from physical interaction or performance. To identify representative product images, the designers were asked to first look at all of the 262 images, and then to group them into three categories: ‘pleasurable,’ ‘displeasurable’ and ‘neutral.’ They were then asked to rank in order the product images from the ‘pleasurable’ group. After this process, it was found that 57 of the product images obtained the top ranking of ‘most pleasurable’ by at least one designer out of the group. Of these 57 images, 11 were ranked as ‘most pleasurable’ by two designers out of the group, 4 by three designers, and another 4 by four designers. These 19 images identified as the ‘most pleasurable’ products by at least two designers were then selected as stimuli for the experimental in-depth interviews. These stimuli reflected a good balance among the three categories, five of the images being kitchen products, six being hi-tech products, and eight being household appliances.

To assure that the 19 stimuli selected by the designers would elicit consistent responses from the student interviewees, the latter were asked to identify before each interview whether the stimuli were pleasurable or not. The results of this question were calculated by using a Chi-square test. Among the 19 stimuli, 16 presented no significant difference (p> .05) (see Appendix), demonstrating that both the designers and the students had a consistent pleasure response to the majority of the chosen stimuli.

In-depth Interviews

Judgment sampling was adopted for this study. This is because young, college-age people, as demonstrated in well-being research, focus more on emotional response, whereas older people tend to focus more on satisfaction (Campbell & Converse, 1976). This implies that young people have stronger emotional responses towards products than older people. Hence, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 30 participants having an average age of 22 years. Of these, 10 were industrial design graduate students and 20 were senior- or junior-year students with industrial design backgrounds. Sixteen of the subjects were female and 14 male. The interviewees were from different parts of Taiwan: 13 from the north, 7 from the south, 9 from the middle of the island, and one from the east.

The individual interviews took place in a quiet room and lasted about 50 minutes for each participant. Before the interviews, the subjects were offered the equivalent of US$6 for their participation. At the beginning of the interviews, the Oxford English Dictionary definition of ‘pleasure’ and the definition of a ‘pleasurable product’ were explained to the participants. In addition, they were also instructed to describe pleasure elicited through the visual appearance of the products and to ignore any pleasure elicited from physical interaction or performance. In each interview, 19 photo cards were randomly displayed in front of the participant from a comfortable viewing distance. The cards were shuffled randomly after each interview to avoid ordering effects. The participant was then asked to examine the 19 stimuli carefully, one by one, and to elaborate on why he or she perceived and derived pleasure from each image. Their responses were recorded for data analysis.

Data Analysis

A three-step process was used to analyze the data. The three steps were: 1) data grouping, 2) secondary level labeling, and 3) primary level labeling (Ulrich & Eppinger, 2000).

Data Grouping

Data collected from the interviews were transcribed into a word processing program. Among the data, a total of 728 key sentences were identified from the responses and provided the basis of data grouping. Data grouping is a procedure for grouping key sentences having similar content. Key sentences describing the same stimulus and judged to be of similar content were first sorted into the same groups, as shown in Column 3 of Table 1. For instance, participants described Sample 1 using the sentences: “The product with transparent material makes me feel pleasant” and “The rounded shape with a matte-finished transparent material caught my attention and evoked pleasure.” Both sentences were categorized into the same group, because their content described the same subject, in this case the transparent material. This step involved repeated and careful reading of the transcribed data in order to develop a clear understanding of the content of each response.

Secondary Level Labeling

Secondary level labeling was the procedure used for labeling the groups that were identified in the previous step. In order to label a group, the key words that could represent each key sentence were first identified in the sentences, and then underlined and highlighted in bold typeface, as shown in Column 3 (see Table 1). These key words were then categorized or refined. For instance, the key words in sentences describing one particular product were ‘transparent material,’ ‘matte-finished transparent material,’ ‘semi-transparent material,’ and ‘material’; these were refined to ‘beautiful material.’ The words ‘beautiful material’ were hence used as the secondary level label representing the key words in this group. The labels were then identified as characteristics of pleasurable form, as shown in Column 2 of Table 1. Other secondary labels chosen for groups of key sentences included the words ‘attractive color’ and ‘delightful shape.” The latter words, ‘delightful shape,’ were chosen to represent the following key words: ‘round and stretched,’ ‘the curve of a human body,’ ‘round and curved shape,’ ‘round surface,’ ‘the shape looked soft,’ and ‘proportions of the shape.’

Primary Level Labeling

Primary level labeling is a procedure for identifying cluster groups according to similarity of secondary level labels, and thus gradually reducing the data to a higher order concept, which is given a primary level label. In this case, the primary labels were the five basic types of pleasurable forms. For instance, the secondary labels ‘beautiful material,’ ‘attractive color’ and ‘delightful shape’ were all associated with aesthetic qualities. Thus, these words were categorized under the primary label ‘Aesthetic Form,” as shown in Column 1 of Table 1. For validation purposes, the process of data grouping, secondary level labeling, and primary level labeling were completed with the assistance of another senior design professional.

After primary level labeling was completed, the frequencies of the key sentences that described the reasons each participant felt pleasure from the products were calculated. For example, as shown in Table 2, Sample 1, 20 key words were extracted related to Aesthetic Form, of which seven were identified as falling under the ‘beautiful material’ label, two under ‘attractive color,’ and 11 under ‘delightful shape.’ In the same sample, 16 key words were found to be related to Bios Form, 12 to Cultural Form, eight to Novelty Form, and one to Ideo Form. Using this identical process, the frequencies of the key sentences of other samples were identified, and the types and characteristics were grouped.

The frequency of the key words and their percentages for each sample are given in Table 3, from which the number of percentages are later used to perform clustering in order to group samples. In the following section on Results and Analysis, the types of pleasurable form for each stimulus are discussed to determine which form caused a sample to appear more pleasurable.

Table 1. Demonstration of data analysis processes (Sample 1 as an example)

Table 2. Examples of key word frequency for Sample 1

Table 3. Key word frequency for each type of pleasurable form (continued below)

Results and Analysis

Five Types of Pleasurable Form

The final results produced 14 characteristics that were classified into five types of pleasurable form: Aesthetic, Bios, Cultural, Novelty and Ideo forms. These five forms, with their associated key words and characteristics, are listed in Table 4. Each of the pleasurable forms is described below.

Table 4. Key word factors, characteristics and types of pleasurable form

Aesthetic Form

The participants’ responses showed that the key words used to illustrate pleasure related to the beauty of a product form could be classified according to three characteristics: beautiful materials, attractive color, and delightful shape. All three of these can be associated with aesthetic qualities; therefore this group was labeled Aesthetic Form. This result suggests that a beautiful product, like a beautiful flower, can please a user, and hence evoke a sense of pleasure.

Some participants commented that they liked semi-transparent and transparent materials because of their clear, glossy, high-tech as well as lightweight look, all of which delivered a strong visual impact and made them feel pleasure. Five participants commented that a material with a ‘see-through look’ allowed them to appreciate the beauty of the inside components or structure, which created an interesting visual impact (See Sample 1, 7, 9, 10, 15). The results also showed that a good combination of different materials in a product can elicit pleasure because of the mix of impressive qualities and beautiful materials. For instance, participants described the Jim Nature TV (Sample 11), constructed from wood chips and plastic panels, as beautiful due to the quality created by the mixed materials. This result supports Jordan’s statement that materials can play a major role in determining how pleasurable a product is or is not for those experiencing it (Jordan, 2000).

Figure 1. Samples used in the interviews (reprinted with permission from manufacturers or design firms).

Product color is the quality that can make the first impression on a consumer and can elicit emotion. This study revealed that participants obtained pleasure by perceiving colors in many aspects. They noticed, for example, ‘an abundance of colors,’ ‘natural color,’ and ‘bright and glamorous colors.’ More specifically, 15 participants commented that they liked a certain lamp because of its light-green color, which gave them some sort of a fresh, comfortable, pleasant feeling (See Samples 4 and 15). And 17 of the responses in the interviews made reference to the bright, candy-looking colors of the I-Mac (Sample 10), which they said delivered a warm and sweet image that, in turn, generated pleasure. This result confirms Khalid’s idea that products can elicit the pleasure of consumers by visually stimulating them with color (Khalid, 2001).

The shape of a product can elicit emotion through those elements that, based on participant responses, convey: a ‘soft and curved surface,’ a ‘big radius,’ ‘nice proportions,’ an ‘aerodynamic surface,’ a ‘symmetrical shape’ or ‘asymetrical shape,’ a ‘simple shape,’ or ‘surface detail.’ Regarding shape traits, many participants commented that a soft and curved surface provided a good, smooth visual experience that elicited pleasure. For instance, both Sample 1 (a cookie container), with its elegant organic shape, and Sample 9 (a computer mouse), with its smooth and simple surface and large radius, elicited pleasure through shape appeal. An aerodynamic shape was another impressive quality for eliciting sensation, as three participants commented that Sample 15 (a lamp), with its inner aerodynamic shape, created a fantasy-oriented visual pleasantness that evoked considerable pleasure.

Bios Form

The results of the analysis also showed that product forms mimicking animals, human figures, objects, or natural elements tended to interest and fascinate the viewers. In the responses, key words related to organic form or objects mimicking natural life were mentioned 206 out of 728 times. These forms tended to connect with the viewer’s imagination and sense of inspiration and were seen as a source of humor and interest that evoked pleasure. According to the different levels of description of mimicked objects, the relevant responses were classified according to three characteristics: ‘concrete form,’ ‘abstract form,’ and ‘interesting movement.’ As these three traits are associated with natural form, this grouping was labeled ‘Bios Form.’ The three traits are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Regarding the trait ‘concrete form,’ the responses demonstrated that product shapes identified as realistically mimicking animals, humans, objects, and nature could evoke pleasure. For example, when viewing the Anna G. corkscrew (Sample 3), which mimics the shape of a woman in a dress, 16 participants responded that the figure’s smiling face delivered a friendly looking image and that the transformation of a human body into a functional object showed extensive imagination. They said that they were fascinated with the idea and that it also elicited pleasure.

The trait ‘abstract form’ designates a product form using an abstracted image of an animal, human, object, or natural form. It was found in the interviews that an abstract product form allowed the viewers more room for imagination in the process of eliciting pleasure. For instance, some participants said that the shape of Sample 16 (a globe-shaped teapot) evoked an image that reminded them of a puppy. This image was reinforced by the parts of the product that suggested associations with the legs, tail and mouth of a puppy. However, when viewing the same object, four participants commented that it looked like a chicken. These results supported Burgess’s statement that animal images are often used in design to give inspiration (Burgess, & King, 2004). Other participants commented that the teapot handle looked like the ponytail of a traditional Japanese warrior. Different participants interpreted the abstract elements differently, but all derived pleasure from the image.

‘Interesting movement’ is a trait that mimics or simulates, in the form of the product, the movement of biological features or formations. The results of the interviews showed that participants could identify and were fascinated by a product image that mimicked a movement or gesture of a human or animal. For example, on viewing the sugar bowl (Sample 6), which has an ‘upside-down cone’ body with three frog-like legs, nine participants described the legs as looking like they were going to jump off the table. This humorous jumping-leg formation fascinated them and thus elicited pleasure. Similar responses were found for the ‘Magic Bunny’ toothpick holder (Sample 5), on which the ‘rabbit ears’ act as a kind of metaphor for the holder’s catch and pull-up operation. This operation created an image of a humorous action that elicited pleasure.

Cultural Form

Cultural form is a form that suggests social meaning and that fits well with social belief systems, values and customs (Arnould & Zinkhan, 2003). Participants based their judgments on their cultural experience and values and described how they would use the products in their daily life in relation to this cultural or value context. There were 156 key word frequencies in the responses that were used to illustrate pleasure towards products relating to social or cultural content. Based on these responses, eight factors were found: style, fashion, literary meaning, status, nostalgia, playfulness, sharing, and display effect. These factors were categorized according to three characteristics: ‘intangible effect,’ ‘tangible effect’ and ‘playful interaction.’ This grouping was therefore labeled “Cultural Form.”

‘Intangible effect’ deals with the inner, intangible level of experience. In this study, the participants mentioned qualities related to style, fashion, pride, literary meaning, and nostalgia. Style has been defined as a fashion that has lasted for a prolonged life cycle (Lin, 2002). Consumers choose and develop their own life style and collect objects that become an extension of this personal style (Arnould & Zinkhan, 2003). Accordingly, the participants in the study expressed ideas that showed they believed that products could shape the identity of their particular style. For example, some of them said they would feel trendy or stylish while using Samples 7, 8, 9, and 10, all products that they identified as being contemporary in style and that in turn elicited a feeling of pleasantness. Another “intangible” quality is literary meaning, which deals with the use of language or other methods as a sign to deliver cultural value to consumers. As Alessi (2000) puts it, objects have a language and they speak to us; and according to Albrecht, Lupton, and Holt (2000), a product can be a container for a story, or, in other words, the features of a product form should be signs that convey meaning or tell a story to the user. When the content of this story is interpreted meaningfully, the resulting cultural information will elicit pleasure. In the interviews, for instance, five of the participants said they felt a sense of fun when they saw the ‘Magic Bunny’ toothpick container (Sample 5). They explained that the rabbit and tube shape that implied the product’s operating process also served as a story-telling metaphor that could prompt the user’s imagination. Similarly, Cummings(2000) has said that products have come to play an increasingly symbolic role in our lives. This concept was evident in the responses of six of the participants when they viewed Sample 2, a juicer set atop very tall legs; owning this product, they said, would be a way to show off their good taste and thus to feel emotionally satisfied, thus in turn making them feel pleasure.

‘Playful interaction’ is a quality that deals with the individual acts and social interactions affected by using objects (Leong & Clark, 2003). Sweet (1998) has stated that, like a toy, the playful effect is the characteristic of a product by which it plays the role of an interesting object in the home. Kitchen products, therefore, can become part of the social media of the kitchen and interactive objects to satiate interactive desires in the kitchen. Some participants in the interviews said they experienced pleasure by physical or visual interaction with the products. When viewing Samples 1, 3, 5, 6, 16, they expressed the idea of wanting to share the products with friends. According to responses of 20 of the participants, the ‘Magic Bunny’ toothpick holder was a good example for illustrating a medium that could spur the imagination and induce playful interaction at the dining table.

‘Tangible effect’ deals with the outer, tangible level of physical form and its application in daily life. Participants commented that a product with more than a functional purpose could play an extra role in their living environment. Hence, a good product, like a painting, should permit being displayed as part of the user’s home decoration. Consumers might display it as a part of their home decoration to illustrate their taste and personal style. Furthermore, the displayed object can become a medium that increases pleasure and life quality from a social interaction perspective. Some participants mentioned that they would like to display such samples as numbers 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 15, 19 in a special space where they could appreciate their beauty and interesting shape and thereby increase the pleasurable atmosphere of their home. For instance, 6 participants indicated that the Juicer (Sample 2) could serve a dual purpose, as a functional juicer and, due to its beautiful proportions, as an artistic sculpture to display in the home. Hence, pleasure could be derived through the enjoyment of making juice and, simultaneously, through the appreciation of the object itself.

Novelty Form

Novelty is a product characteristic that places unique emphasis on concept, form, and methods of feedback. In the responses of participants, key words related to the eliciting of pleasure through creativity and uniqueness of product form were mentioned 77 times. This result showed that the participants were curious about or attracted to products with novelty value. This supports Csikszentmihalyi’s statement that enjoyment is characterized by a sense of novelty (Csikszentmihalyi, 1992). These responses involved factors such as creative material, unique shape, special color, new mechanism, and new concept. These factors were grouped into three characteristics: ‘unique appearance,’ ‘structural innovation,’ and ‘creative concept.’ This grouping was labeled ‘Novelty Form.’

‘Unique appearance’ refers to the creation of new shapes, unique colors, and creative materials. Participants expected to be surprised when perceiving something different or new. Compared with ordinary plastic materials, participants appreciated products that were made using unique and creative materials that created a soft, clear and modern look, and they felt that such materials elicited surprise and pleasure.

‘Structural innovation’ addresses the creation of a new structure, particularly when it is a structure that relates to the consumer’s interaction with the product. Participants appreciated the products that had a clever structure, and they enjoyed using ones that performed clever functions. For instance, participants noticed the unique ball joint mechanism design of the computer screen shown in Sample 8, which allows users to change the angle of the screen simply by pushing it. This special device incorporated a unique adjustment system that evoked pleasure.

‘Creative concept’ refers to a new solution to a product’s operation or function. The participants stated that they appreciated a designer who could offer new solutions for old objects. The design of the Globo teapot (Sample 16), for instance, demonstrated a clever idea of using an interesting form in a new way to stabilize the teapot; this was something that surprised the participants.

Ideo Form

Key words that expressed pleasure towards a product because it represented a personal favorite, or because it reflected the participants’ values, were mentioned 49 times. These words were thus grouped into two characteristics: ‘personal preference’ and ‘personal value,’ both in relation to idea or concept. This group was accordingly labeled ‘Ideo Form.’ Ideo form addresses personal values and preference. Products at this level help us to feel more like who we believe we are or who we would like to be (Albrecht, Lupton & Holt, 2000). Participants, in this regard, displayed their own preferences when appreciating and choosing the products they desired.

‘Personal preference’ addresses a person’s preference towards a product. For instance, some participants in the interviews responded that they personally preferred a computer screen with a white case because this design matched their personal preference, and thus evoked pleasure.

‘Personal value’ regards a person’s belief in the value of a product. For instance, five participants experienced pleasure when they perceived Starck’s Juicer design (Sample 2). They desired the product to be part of their personal collection and believed, therefore, that it had value. In another example, eight participants said they believed that environmental protection was an important issue to address in a product’s value, and, therefore, they would feel happier to own a Jim Nature TV designed by Starck, because this product not only was made of materials with natural beauty, but it also demonstrated symbolically the idea of using ecologically friendly materials. Participants felt good towards this design because they believed in its ecological value.

Pleasurable Form and Product Types

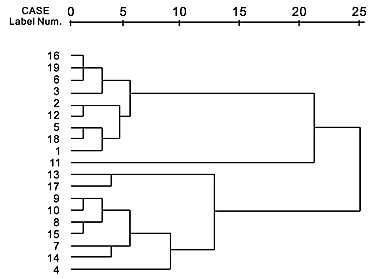

In examining the 19 sample types, the hierarchical cluster method was used. The samples were clustered by calculating the number of percentages of each sample (see Table 3). The statistical results reveal that there are four clusters when the cutting point is located at 14 scales, as shown in Fig. 2. The cutting point was determined at 14 scales because it can display the three types of products discussed in this paper. Cluster 1 contains Samples 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 12, 16, 18, and 19. Among these samples, seven are kitchenware and two are household appliances. Cluster 2 contains Sample 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, and 15. Among these, five are hi-tech products and two are household appliances. Cluster 3 contains only one sample, which is a household appliance. Cluster 4 contains Sample 13 and 17, which are household appliances. In addition, the mean and the SD of each pleasurable form of the four clusters were calculated and are shown in Table 5. The result shows that, among the five pleasurable forms, Cluster 1 has the highest mean for Bios Form, Cluster 2 the highest for Aesthetic Form, Cluster 3 shows both Novelty and Ideo Form, and Cluster 4 shows Aesthetic Form. Based on the results of Fig. 2 and Table 5, it can be seen that the different product types scored differently on the type of pleasurable form in eliciting consumer pleasure. These different scores are discussed in the following paragraphs.

In Cluster 1, seven out of nine samples are kitchen products (Samples 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 16, 19) and reveal the highest mean on Bios Form. This result implies that kitchen products tend to rely on Bios form to elicit pleasure. In Cluster 2, five out of seven samples are hi-tech products (Samples 7, 8, 9, 10, 14) and the focus is particularly on the Aesthetic Form type. This result implies that hi-tech products have great potential to successfully evoke a user’s pleasure by emphasizing material, color, and shape traits. Finally, Sample 11 in Cluster 3 and Sample 17 in Cluster 4 are household appliances and reveal the highest means on Novelty, Ideo and Aesthetic forms. This may be because household appliances rely on various types of pleasurable form, depending on their attributes and usage environment.

Figure 2. Results of cluster analysis of product types

Table 5. Mean and SD of each pleasurable form of the four clusters

The Ranking of Pleasurable Product Forms

In examination of the means, Table 5 shows that nine out of 19 samples scored highest on Aesthetic Form (Samples 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, and 17), nine on Bios Form (1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 12, 16, 18, and 19), one on both Novelty Form and Ideo Form (Sample 11). These results imply that Aesthetic and Bios forms have more potential than the other three forms to attract a consumer’s attention and thus evoke pleasure. This finding could indicate that the participants also tended to focus primarily on a product’s explicit information, which derives mainly from Aesthetic and Bios forms in eliciting pleasure. This would support the finding that people who score high on the hedonic scale are indeed more interested in products that contain attributes which describe aspects of a product’s form (Creusen & Snelders, 2002).

In Table 5, the results also show that only Sample 11 exhibited an emphasis on the Novelty and Ideo types of pleasurable form in evoking consumer pleasure. Regarding Novelty Form, it is possible that the stimuli samples, having been already on the market for some time, were not perceived as fresh or novel enough by the participants. For instance, some participants commented that, at one time, they would have been surprised and felt pleasure on seeing products made with unique materials and in unique shapes; this would have been when they first saw such products on the market several years earlier. This implies that, when launching a new product, a new fresh look could be an important consideration for eliciting consumer pleasure. Only Sample 11, the Jim Nature TV, was identified with Ideo Form, perhaps because the concept behind the Ideo product form is difficult to transfer to a product’s design and also hard for people to perceive. Therefore, learning what can connect with users’ personal values and thus elicit pleasure is a challenge for product designers who wish to emphasize pleasure through the Ideo approach.

Conclusions

The ability of a product to produce pleasure is an important concept in the competitive marketing of consumer products. This research examined consumer products and identified types of pleasurable form and their characteristics in order to better understand the forms of pleasurable products. The following three conclusions have been drawn from this research.

First, five types of pleasurable form and 14 associated characteristics were identified and discussed. By understanding each type of pleasurable form and its characteristics, designers can apply this knowledge to designing pleasurable consumer products aimed particularly towards the young, college-age market.

Second, Aesthetic and Bios forms in the design of a consumer product have more potential than the other three to attract a consumer’s attention and elicit pleasure. Therefore, it is suggested that enhancing a product’s Aesthetic or Bios form will produce an effective means for developing its pleasure-giving potential in the young consumer market.

Third, different types of products rely on different emphasis of product form to elicit consumer pleasure. This paper shows that hi-tech products tend to rely on characteristics related to Aesthetic Form, and kitchen products tend to rely on Bios Form characteristics. Hence, it is suggested that designers can emphasize color, material, and shape when designing a hi-tech product, and that they utilize Bios forms and, further, embed a story or literary meaning into a product’s shape when designing kitchen products.

This study focuses on consumer pleasure evoked through the visual appearance of household products. The stimuli selected in this research showed a good balance among the three categories, as mentioned earlier. However, they did not ensure a good balance in all spectrums of product attributes. To more fully balance product attributes, alternative methods for selecting stimuli (e.g., the orthogonal array method or conjoint analysis) are suggested for future studies. Furthermore, the participants in this research were college students only, a group that may not represent the broader consumer population. Hence, to further understand the broader market, it would be valuable to study participants drawn from a variety of age groups (e.g., housewives) to confirm the findings regarding pleasurable responses. In addition, the pleasure elicited through actual physical operation of a product and actual experience of its performance would also be valuable for understanding pleasure responses, and such an approach is suggested as a direction for future studies of product pleasure.

References

- Alessi, A. (2000). The Dream Factory. Electa/ Alessi, Italy.

- Albrecht, D., Lupton, E. and Holt, S. (2000). Design Culture Now. Laurence King, London.

- Arnould, E., Price, L. and Zinkhan, G. (2003). Consumers, (2ed edn). McGraw-Hill Education, USA.

- Bloch, P. H. (1995). Seeing the ideal form: product design and consumer response. Journal of Marketing 59, 16-29.

- Burgess, C. S. and King, M. A. (2004). The application of animal forms in automotive styling. The Design Journal, 7(3), 41-52.

- Campbell, A. and Converse, P.E. (1976). The quality of American life. Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

- Cho, Hyun-Seung and Lee, Joohyeon (2005). Development of a macroscopic model on recent fashion trends on the basis of consumer emotion. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 29 , 17-33.

- Creusen, M. and Snelders, D. (2002). Product Appearance and Consumer Pleasure. Taylor and Francis, UK.

- Crilly, N., Moultrie, J. and Clarkson, J. P. (2004). Seeing things: consumer response to the visual domain in product design. Design Studies, 25, 547-577.

- Crossley, Lee (2003). Building emotions in design. The Design Journal, 6(3), p35.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. & Rochberg-Halton, E., (1981). The meaning of things. Cambridge University Press, London.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1992). Flow: the psychology of happiness. Rider, London.

- Cummimgs, N. and Lewandowska, M. (2000). The value of things. Birkhauser, UK.

- Desmet, P. and Overbeeke, K. (2001). ‘Designing Products with Added Emotional Value: Research through Design’. The Design Journal, 4(1), 32-47.

- Dubá, L. and Le Bel, L. J. (2003). The content and structure of laypeople’s concept of pleasure. Cognition and Emotion, 17(2), p266.

- Jordan, P. (1998). ‘Human Factors for Pleasure in Product use’. Applied Ergonomics, 29(1), 25-33.

- Jordan, P. (2000). Designing Pleasurable Products. Taylor and Francis, UK.

- Janlert, L. and Stolterman, E. (1997). ‘The Character of Things’. Design Studies, 18(3), 297-314.

- Khalid, M. H. (2001). Can Customer Needs Express Affective Design. International Conference on Affective Human Factors Design, Asean Academic Press, Singapore.

- Koch, R. (1997). The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More with Less. Nicolas Brealey, London.

- Leong, D., and Clark, H. (2003). Culture-based knowledge towards new design thinking and practice- A dialogue. Design Issues, 19(3), 48-58.

- Lin, C. (2002). Consumer Behavior. Bestwise Publisher, Taipei.

- Marzano, S. (1998). Thoughts. Blaricum, the Netherlands: V+K Publishing.

- Seligman, E.P. Martin (2005). Time magazine. February, 2005, USA.

- Simpson, J.A., and Weiner, E.S.C. (1989). The Oxford English Dictionary (2nd Ed). Clarendon Press, UK.

- Seligman, M. (2002). Authentic Happiness: using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Arthur Pine Associates, USA.

- Sweet, F. (1998). Alessi: Art and Poetry. Thames and Hudson, UK.

- Tiger, L. (1992). The Pursuit of Pleasure. Transaction, London.

- Ulrich T. K. & Eppinger D. S. (2000). Product design and development. McGraw-Hill, USA.

Appendix

Chi-square test between designers and students (continued below)