Contemporary Ceramic Design for Meaningful Interaction and Emotional Durability: A Case Study

Oaklands College, St Albans, UK and Emma Lacey-engaging ceramics, London, UK

The paper presents a case study of the design of emotionally durable ceramics, which is then applied in real commercial contexts. It illustrates how designers can be inspired by hand crafted unique objects, and how designers in turn can translate some of their qualities for use in mass-produced objects. Examples of existing commercial products are given, which the author feels stimulate an emotional connection to ceramics. Her own, personal experience of these objects is related, giving insight into how these products have inspired her work. The author explores, for example, what factors determine why a mug is someone’s favorite, and what determines a meaningful experience with cups. Interviews and questionnaires are used to gather information about peoples’ relationships with ceramic cups and mugs, and Donald Norman’s (2005) levels of cognitive processing are then used to categorize and analyze the results. Suggestions are made as to whether one’s response to products can stem from design, or happen regardless of it. The title of this paper was inspired by Jonathan Chapman’s book, Emotionally Durable Design. This book provided a useful language to describe the contemporary relevance of this project, which was initiated by the ambition to design responsible, well made, tactile products which the user can get to know and assign value to in the long-term.

Keywords – Emotionally Durable Ceramic Design, Meaningful Experience, Value, Longevity.

Relevance to Design Practice – Provides insight into a practical design process showing how Design and Emotion theory, ethnographic research and studio practice can inform the design of physical solutions.

Citation: Lacey, E. (2009). Contemporary ceramic design for meaningful interaction and emotional durability: A case study. International Journal of Design, 3(2), 87-92.

Received March 09, 2009; Accepted July 17, 2009; Published August 31, 2009

Copyright: © 2009 Lacey. Copyright for this article is retained by the author, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

Corresponding Author: info@emmalacey.com

Introduction

This paper describes an ongoing explorative design project through the author’s professional practice that began in 2005 as an AHRC (Arts and Humanities Research Council) funded project. In a world saturated with products – many of which are used briefly and then thrown away – this project aims at producing ‘fewer better things’ (personal communication, February, 2007), for example ceramic objects which transcend the fast moving home-ware trends and remain loved and relevant over extended time. As observed through personal experience, value beyond monetary cost can be assigned to individual handmade products. It is this uniqueness and integrity of material and process seen in handmade crafts that are hoped to be imbued into commercial products in order to make them emotionally durable.

A contradiction in terms provided the initial design problem. How could one design ‘unique’ pieces that would be valued on a personal level and which could also be industrially mass produced? The notion of integrity is central in this contradiction. An intuitive mapping of the word by the author was used to instigate design methodology and to find relevant research sources. (Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Designer's integrity mindmap.

Words such as value, meaning, user experience, accessibility, personal, and tactile led to the identification of relevant texts and methods of research involved in the design project. These included experiential and visual research, ethnographic studies, theoretical investigation and studio practice. Methods were explored fluidly and concurrently over a period of two years. These studies are difficult to separate into isolated studies, however this paper describes some of the explorations in separate sections.

The first section describes examples of industrially produced ceramic objects that were used as a source of inspiration because they were felt to provide the meaningful experiences hoped for in the case study.

The second section describes an explorative investigation into user attachment to ceramic objects. Donald Norman’s (2005) ideas on cognitive processing were used as the basis for interviews with people about their emotional connections with ceramic teacups or mugs. These interviews confirmed the assumption that the vessel used to drink tea was not only a highly ritualistic object for use in both formal and informal tea ceremonies, but also an excellent indicator of our personal, meaningful relationships with objects. Moreover, this vessel was also found to be useful as a vehicle to explore how and why we attach value to such a simple everyday objects.

Besides the user research and semantic explorations, a significant amount of time was spent by the author in the studio testing ideas and forms for products that might stimulate interaction and thus encourage meaningful experiences. A selection of these tests is highlighted in the final section of this paper, and a description of three main outcomes is given. These designs aim to illustrate how an investigation into meaningful interaction with ceramic objects might be realized through emotionally durable ceramics. This paper evaluates these designs and explores them against initial research and through informal interviews. Feedback is also gained as a result of launching and exhibiting the products.

Meaningful Experiences with Industrially Produced Ceramics

During the research and design development phase of the project, the inspiration was taken from existing examples of ceramic tableware which were thought to offer layers of experience beyond simply eating and drinking.

Hella Jongerius’ Non-temporary ceramics range of tableware (Figure 2) for Royal Tichelaar Makkum provides the consumer with insight into the process of creation as well as the properties of the ceramic material. The half-dipped glaze not only illustrates how the shiny surface is applied (slightly differently each time), it also reveals areas of the clay body showing the different qualities of color where the hand-painted floral decoration crosses both glazed and unglazed surfaces. A meaningful interaction is prompted by the honesty of material and considered surface application, which encourages touch.

Figure 2. ‘Non-temporary ceramics’ for Tichelaar Makkum (Designed by Jongerius, 2005; reprinted with permission).

These designs are similar to the qualities in the author’s Everyday range of products which provides textural differences and an interruption in form, created by pushing the clay when it’s soft (Figure 3). This opportunity for exploration of the object can be seen to bring the user closer to the making process and to the narrative of the piece’s life before point of sale, thus providing a meaningful experience beyond the utilitarian function of a bowl or plate.

Figure 3. Everyday mugs (designed by the author in 2002).

In the Non temporary ceramics range (Anonymous, 2005), a middle point between the industrially produced and hand-painted gives individuality to a commercial product and also protects the heritage of the company, and skill of it’s crafts people, which adds value. However, if the obviously handcrafted elements were removed entirely, would it be possible to achieve a similarly meaningful experience?

A teacup, which the author discovered during the Milan Furniture Fair in 2006, provided great inspiration to this study in that it was a mass produced product that still invited the consumer to have a meaningful interaction with it. The TAC01 teacup (Figure 4) had an incredible lightness due to the fine porcelain. This surprising element led to an investigation of the foot rim (a ceramist’s habitual reflex – to read the back stamp), which provided the discovery that the bottom of the cup was completely glazed. This unusual element led to an exploration of the fine top rim of the cup, which was unglazed but polished (necessary for production purposes). The experience of surprise triggered a process of discovery, thus providing through its design features a conscious interaction that was meaningful and valuable. This interaction was also of great value to the project as this experience clearly inspired one of the pieces described in the third section of the paper (see ‘Click’ Figure 5).

Summary

The design explorations resulted in the main proposition that design (or craft) features that take the user on a journey contribute to meaningful experience. In the case of hand-made or hand-finished products, visual clues, such as an unglazed area or an irregularity in form, can lead to tactile investigation of these unique or seemingly unique qualities. It is this level of consciousness required to explore the object in detail that is the aim of the author’s own designs, in hopes of enhancing the user’s initial experience of an object in a way that encourages one to return to explore the details again and again.

The surprise element described in the experience of the TAC01 can be seen as a cue to explore the product. This may have impact on the long-term value of the piece as described in Surprise and Emotion (Ludden, Hekkert, & Schifferstein 2006), which asserts that “(…) surprising products can remain interesting in the long term, because it is fun to show surprising products to other people.” (p. 5). This is certainly true in the present design study, and this particular example has proven useful to the author in numerous lectures and presentations.

Figure 4. ‘TAC01’ teacup and saucer

(designed by the author in 2004).

Emotional Durability and the Empathy with the Mug

The examples in the previous section present personal design ideas and propositions about what gave those products and experiences their value. The next step in the project, therefore, was to perform some user tests to gauge and further develop these ideas about our attachments to objects.

In his book Emotionally Durable Design (2005), Jonathan Chapman proposes that we might address issues of sustainability through exploring product lifespan and relating this to peoples’ emotional needs. He describes a ‘utopian futurescape’ where design is derived from “profound and sophisticated user experiences that penetrate the psyche over time” (p. 83). Examples of this may include refilling a fountain pen with ink or “re-honing the blade of a sushi knife on a well-worn whetstone” (p. 83). These simple, meditative experiences describe the repair and care which takes place over a long period of time, and demonstrate what Chapman describes as having empathy with the products we choose to live with.

Assuming that ceramic tableware offers relevant examples of our empathy towards objects, research was conducted through interviews and questionnaires into people’s specific and personal attachments to cups and mugs. It was hoped to ascertain whether there were prompts which could be designed into products to encourage meaningful interaction.

Method

In this study, 30 people ranging in age from 17 to 75 volunteered to participate. Eight participants were studying or working in fields related to design, and the professions of the remaining participants ranged from administration through education and public services. Participants photographed or sketched their favorite and least favorite mugs or cups. They were then asked to comment on why a mug or cup was their favorite, and why another was their least favorite. In addition, informal interviews about their favorites were used to generate rich insight.

Results

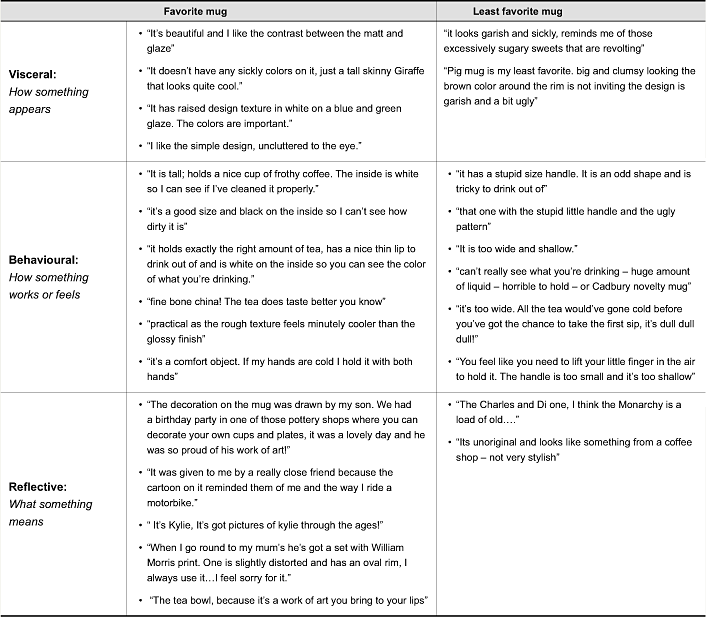

Donald Norman’s (2005) three levels of cognitive processing were used to categorize key statements of the respondents. This allowed the responses to be analyzed, identifying the participant’s levels of cognition in terms of form, function and personal meaning (a selection of the results are given in Table 1).

Table 1. Results summary – Favorite Mug interviews (2005-2007).

Though it was not intended, almost all participants chose to describe a favorite mug rather than a cup and saucer. This suggests the mug as a universal and emotive object that penetrates personal experience and transcends gender, background and circumstance. The ritual attached to the cups and saucers and also some treasured Japanese tea bowls, which are formalized in terms of their performance and occasional but repetitive use, can be seen as adding value to the object in a cultural or social sense, rather than a personal one.

Results categorized under Norman’s (2005) visceral and behavioral levels of processing clearly describe visual properties and ergonomic qualities. Individual taste is apparent, but it can be generalized that weight, size, color and shape are important and that, obviously, the designer may use these characteristics to stimulate an emotional response (as seen in examples provided in the previous section). In contrast, reflective answers given in the interviews were much more unique. Interviewees talked about the people who had given them the cups and the symbolism of the objects. They were, as Norman describes, more to do with, “the meaning of things, the personal remembrances something evokes…it is about self image and the message a product sends to others” (p. 84).

Summary

The favorite mug research identified the breadth of individual taste and personal attachment to ceramic mugs, proving that empathy is assigned for both physical and emotional reasons, which are accredited to personal taste. The implication for design may be to allow for choice within a set of objects so that individuals can choose and defend their own favorite, thus demonstrating emotional attachment.

The reflective answers provided levels of personal attachment that the designer cannot (or perhaps should not) try to contrive. The user autonomy, which is asserted here, is evidently connected to the very individual, social, cultural and emotional value of the object and perhaps suggests that the designer should look at ways in which to leave space in the design for the consumers’ own interpretation, rather than design a piece to be used only as directed by the designer. For example, enabling the user to personalize an object or adapt the way it is used. This concept is illustrated in the following section.

Studio Practice and Engaging Teacups

The research provided three main objectives for studio investigation. The first was to add an element of surprise that would nudge the user into exploring the object consciously. The second was to incorporate a unique element that would give the object an individual identity, again to nudge the user into closer inspection. The third was to allow for a level of interaction which could be personal and which was beyond simply drinking tea or coffee. What follows is a description of the three products of these objectives.

Preliminary tests using teacups with unexpected weights and unusual forms and functions created a playful process which tackled the concept of unique drinking rituals. Pieces that involved a group of users all having to pick up and put down the cup at the same time were explored. Elastic bands were used to control the positioning of the cups in their saucer. Multiple cups were designed for one saucer, creating interesting balancing acts from the rolling bottomed cups which could only stand in their companion saucer, but which were sometimes steady on the table (according to the amount of liquid inside). Ultimately, however, the designs needed to function effectively in real commercial contexts and also needed to be viably produced in ceramics factories, so the unique design elements needed to be subtle enough not to interfere with function or realistic production processes.

Cup and saucer forms were modeled in plaster and then cut and manipulated to change the angle at which the cups would sit, the way they would be held and used, or how they would rest in the saucers. As the experiments were developed and refined, the limitations of the ceramic material and production processes influenced the engineering of these models and led to the production of three teacup ranges. The pieces were test manufactured in the UK and Germany, proving that the shapes could withstand the high temperatures of both porcelain and bone china firings.

The Click cup’s particular function (Figure 5) is its theatrical performance. If positioned correctly, the cup rocks from a tilted to an upright position when liquid is poured in, integrating a surprise within the user experience. The sloping recess in the saucer, which allows the cup to sit at an angle, gives the user an opportunity to then play with the weight and position of the cup and become acquainted with it over time.

Figure 5. Click (designed by the author in 2007).

The Slide cup and saucer (Figure 6) replaces the conventional shuffle (movement between cup and saucer), with a sliding motion. This fluid movement allows the user to interact with it either consciously or in a more unconscious manner, as when tapping one’s fingers on the table, or doodling. As people often re-interpret the objects they own, both the generous cup and saucer can also be used as bowls. The shape of the saucer means that a variety of round bottomed vessels can be nestled into it, which provides a degree of user autonomy in that the form or function of the piece can be changed. This compliments nicely Donald Norman’s reflective level of cognitive processing, where the user is able take a conscious role in the object’s meaning or purpose.

Figure 6. Slide (designed by the author in 2007).

The Duo tea and espresso sets, (Figures 7 and 8) replace the typical circular shape of a cup with a subtle oval. Its elliptical form changes the tactile nature and ergonomics of the object, nudging the user into consciously articulating a comfortable drinking position. The handle, which is attached in varying positions on each cup, further accentuates this function. The aim is that the user becomes attached to their chosen cup from a seemingly standard set through selecting a favorite handle position, as well as through finding a preferred way of drinking from it. Not only does this add the opportunity for personal value to be assigned (as seen in the favorite mug interviews), it also connects the user with the manufacturing process. The connection occurs when the user considers the handle, which was placed on or off centre by a skilled potter in the factory. This effect is comparable to that received by Hella Jongerius’s Non temporary range described earlier. The initial exploration of the Duo cups, which is provoked by the unusual shape, should ultimately encourage a more subtle fondness, growing over time, ideally until the cup becomes valued as the favorite.

Figure 7. Duo espresso sets (designed by the author in 2007).

Figure 8. Duo espresso sets (designed by the author in 2007).

Conclusions

These three designs make ideas about emotional interaction with tableware objects in a contemporary context tangible. Each design has features that are a subversion of form or function that encourages the user to interact with, and experience, the object on a conscious level. As the project aim was to design emotionally durable ceramics for real commercial contexts, it is relevant to evaluate them from this point of view. Feedback on the products has been collected through real life scenarios rather than contrived through further questionnaires.

Though the Click cup is not in production and cannot be evaluated as an everyday piece, it has been used effectively to demonstrate the element of surprise during lectures and exhibitions. Alex Fraser (a trained Master in the Japanese art of tea drinking) compared using the cup to the mindful performance used in the Japanese art of drinking tea. He states that, “the novelty and surprise can create an impression over time, through repetition” (personal communication, May 14, 2007). Demonstration of the piece at the 2008 Design and Emotion conference in Hong Kong evoked a pleasing reaction from the audience, a number of which queued after the presentation to explore the piece further.

Demonstration of the Slide cup and saucer at the same event resulted in the purchase of two pieces. The buyer stated on her blog that “the simple motion is so Zen-like.” She uses one at home and one in her studio.

The Duo espresso sets are now being produced in a factory in Stoke on Trent in England, and are being sold in design boutiques both in Paris and the UK. These, particularly, seem to evoke emotional exclaims of affection, perhaps due to their elegance and petit size. The Duo tea cups are also about to be stocked and used at the gallery and restaurant Sketch in London – a venue showcasing design objects and priding itself on the experience it gives its customers. The owner, Mourad Massoud, exclaimed that the 90-degree angle position is clearly the right one.

At a recent trade show, it was noted that women tended to go for the angled handle on the espresso cup and men the centre handle position, though no scientific evidence can be drawn from this.

A couple who bought a prototype set of Duo cups demonstrate a personal relationship with the cups in describing their daily morning ritual: “He puts the kettle on and I get the cups and saucers out. I use the 90-degree angled handle, as it feels more practical, more right. He has chosen the 45-degree angled handle; he’s more experimental and likes more obscure objects, but he insists his one is the right one. Some mornings we joke about swapping mugs but it never happens.”

It is this last description which best satisfies the aims and potential for emotional durability. The decision making process and discussion as to which handle position is the ‘right one’ allows the user to assert their identity, as described by Norman (2008) when describing the reflective level of processing. It also involves a level of conscious engagement that can encourage meaningful interaction in terms of the user consciously articulating a preferred ergonomic, thus attaching personal preference to the chosen favorite. Also, a social interaction is stimulated which adds to the emotive value of the experience.

Ultimately, the objects will have to be reviewed over time to truly assess their emotional durability. The initial feedback, however, suggests that those engaging with the pieces are making a decision to choose something slightly unusual, which is also more expensive than the average mug, cup or saucer, so are assigning value from the start.

It will be interesting for further study to question and observe users in the Sketch gallery, once the cups are stocked. Another interesting design opportunity is to include a feedback card in the packaging of the Duo tea sets, when they are officially launched in August, 2009.

Acknowledgments

The Author would like to express thanks to the Arts and Humanities Research Council for supporting the project and providing invaluable funding. Also thank you to Kahla Porzellan, Germany and Dudsons Pottery, UK for generously offering factory space and time for production testing.

References

- Anonymous (2005). Hella Jongerius: The European design show. Retrieved Octorber 5, 2007, from http://www.designmuseum.org/design/hella-jongerius

- Chapman, J. (2005). Design for empathy: Emotionally durable objects and experiences. Sterling, VA: Earthscan.

- Ludden, G. D. S., Hekkert, P., & Schifferstein, H. N. J. (2006, September). Surprise and emotion. Paper presented at the 5th International Conference on Design and Emotion, Goteborg, Sweden.

- Norman, D.A. (2005). Emotional design: Why we love (or hate) everyday things (2nd Ed.). New York: Basic Books.