Engagements and Articulations of Ethics in Design Practice

Christian Dindler *, Peter Gall Krogh, Kasper Tikær, and Peter Nørregård

Department of Digital Design and Information Studies, Aarhus University, Aarhus N, Denmark

While ethics has been part of design research for decades, few studies have explored how designers engage with ethics in practice. Based on interviews with 11 practitioners in design consultancies, this paper explores how ethics is understood and dealt with in commercial practice. Based on an analysis of the interviews, we present six themes that capture how practitioners articulate the concept of ethics, how they distinguish between personal and organisational ethics, and how this relates to serving clients with potentially conflicting agendas. Moreover, the study demonstrates that practitioners do not typically use methods or procedures for dealing with ethics, but rely on ongoing and sometimes ad hoc dialogue. Based on these results, we suggest promising avenues for future work relating to concepts for articulating how ethics is dealt with in the design process and how design activities give rise to different levels of ethical concerns.

Keywords – Design Ethics, Design Practice, Human-Computer Interaction.

Relevance to Design Practice – The results of this study provide a foundation for practitioners to reflect on how they understand and deal with ethics in their practice.

Citation: Dindler, C., Krogh, P. G., Tikær, K., & Nørregård, P. (2022). Engagements and articulations of ethics in design practice. International Journal of Design, 16(2), 47-56. https://doi.org/10.57698/v16i2.04

Received November 11, 2021; Accepted August 2, 2022; Published August 31, 2022.

Copyright: © 2022 Dindler, Krogh, Tikær, & Nørregård. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: dindler@cc.au.dk

Christian Dindler is associate professor of participatory interaction design at the Department of Digital Design and Information Studies at Aarhus University. In his research, Christian focuses on the ethics of designing digital technology and the effects that interaction design processes have on individuals and organisations. He has engaged with these issues in several ways, including studies of how participants experience taking part in design, how ethics is dealt with in design, and how children can be empowered to critically and constructively engage with digital technology. In his research practice, Christian works in close collaboration with private and public partners to develop knowledge and solutions that are grounded in practice and provide value for the partners involved.

Peter Gall Krogh is trained as an architect and product designer. He is professor of digital design at the Department of Digital Design and Information Studies at Aarhus University and associated with Politecnico di Milano. Prior to this, he was professor of design at Aarhus School of Architecture, visiting researcher and professor at TU Eindhoven, Hong Kong PolyU, and Jiangnan University. He contributes to service and interaction design both in practice and by theorizing based on co-design techniques, with a particular interest in aesthetics, collective action, and proxemics. In recent years this has been applied in relation to designing for patient experiences in healthcare. His recent book, Drifting by Intention: Four Epistemic Traditions from within Constructive Design Research, describes what design looks like and how it can be approached when developing knowledge is as equally important as providing opportunities by design.

Kasper Tikær holds an MA in digital design from Aarhus University where he specialised in the emerging field of ethics in the context of digital design. He has since been employed as a UX-researcher and product designer. He is a strong advocate for ethics in the professional field of digital design and seeks to expand the understanding of ethics to improve design practices.

Peter Nørregård holds an MA in design and organisational change, and is the founder Playful Innovations. At Playful Innovations, Peter facilitates large-scale innovation and product development projects for public and private organisations as well as start-ups. He focuses on building long-term sustainable innovation capabilities, emphasizing how ethics and responsible innovation can play an active and differentiating role in the innovation process. Peter serves as external lecturer at IT University of Copenhagen, where he is engaged with investigating how values and ethics can be better understood and engaged with in the innovation and design of digital products and services.

Introduction

Design has gained momentum as an approach for addressing problems within a wealth of domains. In the research and practices associated with designing digital technology and services, there is a growing realisation that technology has a major impact on our culture, from the tools for work to the devices that mediate the intimacies of everyday life. With this realisation has followed a concern for the responsibility and obligations of the designers who shape such digital products and services. In practicing design communities and society at large, this concern has sparked a renewed interest in ethics, manifested in debates around data, privacy, and algorithms, and the responsibilities that fall upon companies, institutions, and individual designers. The forums and writings directed at practicing designers bear witness to the increased attention to ethics which is regularly addressed in practice-based magazines, books, and online debates. Here, tools, guides, and reflections from practice are abundant and provide a considerable resource for designers seeking actionable tools and ideas for dealing with ethics. In academic design research, ethics has a long history, but despite continued interest, relatively few studies exist that explore how practicing designers understand and deal with ethics as part of their practice (Gray & Chivukula, 2019; Chan, 2018). Most contributions deal with ethics from a philosophical, theoretical, or educational perspective, seeking to define, nuance, and understand the nature of ethics in design. When considering the two sources of knowledge about ethics—the academic and the practice-based—what is striking is that despite the fact that they deal with almost identical issues, there is little exchange between the two; few papers deal with commercial practice, and it is rare to see practitioner forums leveraging knowledge of design ethics from the academic literature. As such, the discourse on design ethics resembles the branching out of design thinking discourse described by Johansson-Sköldberg et al. (2013). While there may be good reasons for having different discourses on design ethics, there are also good reasons to consider possible exchanges between research and practice. These exchanges could potentially yield robust theoretical conceptions of ethics in design that are grounded in practice, and exchanges could provide the opportunity for researchers and practitioners to create concepts and tools that are attuned to practitioners’ work practices. To paraphrase Stolterman (2021), in order to support or improve ethics in design, we need to develop our understanding of the nature of ethics in design.

In this paper, we address the issue of ethics in design practice by exploring how 11 designers, working in commercial settings, understand and engage with ethics as part of their design practice. Our intent is not to prescribe how practitioners should deal with ethics in practice but to shed light on how ethics is actually perceived and dealt with in commercial design. We believe that developing our understanding of ethics in practice provides an important foundation for developing the area of design ethics in general and creates the potential for developing tools, methods, or frameworks for supporting practitioners. Other scholars have suggested similar directions, arguing for the need to better understand ‘in-action’ ethics (Frauenberger et al., 2017) and studying ethics ‘on its own terms’ (Chivukula et al., 2020). The contribution of this study is two-fold. First, we provide six themes that shed light on how practitioners in design consultancies understand and deal with ethics. This contribution adds to prior accounts of how ethics unfolds in practice, as such accounts remain sparse at present. Second, we identify two areas in particular where our results open up avenues for future work. These relate to concepts that help practitioners focus on ethics in the design process and identify how different design activities spur different levels of ethical issues.

Related Work

Ethics in and by design is a long-standing issue and can be traced throughout history as both ethical imperatives for design practice and theoretical positions for ethics in design. Regarding the former, industrialization was critiqued through movements like Arts and Crafts (Morris, 2002) that were fuelled by social indignation and its ethics. An aesthetic expression of an ethical critique and imperative (within design, how to do what is considered ‘good’) has been the foundation for many of the design movements in the 20th century, which have typically been articulated in written manifestos, such as the Bauhaus Manifesto (Gropius, 1919). Design thinkers and practitioners such as Papanek (1972) and Aicher (2015) have philosophized and strongly expressed concern for the ethical consequences of product design in particular. During the 1990’s sustainability movement, Manzini (1999) argued that the design of services and systems of circulation should reduce the total number of products produced, which was echoed and expanded by Thackara (2015), who urged us to learn from local practices to achieve a sustainable style of life. In recent years, public turmoil regarding data, machine learning, and surveillance has sparked renewed societal and ethical criticism of technologies and their businesses models (e.g., Zuboff, 2019; O’Neil, 2016).

Looking at the academic literature, the writings on ethics and design have evolved in several dimensions, yet adequately covering the issues is difficult as they weave in and out of different forums. Here, we briefly take stock of the literature, starting from that which is most closely tied to design research venues, before moving into literature related to technology and HCI. In doing so, we trace how ethics has been conceptualised, addressed, and studied within different disciplines that engage with ethics in design.

On an overarching level, classical philosophical positions within ethics have been discussed in terms of their relation and applicability to design. Mitcham (1995) provides a useful discussion of the potential of several classical approaches, including deontological and consequentialist ethics. Among the most prominent positions addressed in design research literature is that of Aristotelian ethics, and several authors have argued that this provides a suitable frame for design (e.g., Jonas, 2006; Mitcham, 1995; Bousbaci & Findeli, 2005), while others look to Sartre’s ethics (d’Anjou, 2010), phenomenological approaches (Akama, 2012), and the ethics of Levinas, Derrida, and Dewey (Steen, 2012, 2013). Another significant strand of the literature deals specifically with the ethics of designed artefacts. In their manifesto, Fry and Dilnot (2003) argue that design is always either ethics materialised or ethics neglected. Similar ideas are expressed by Tonkwise (2004) and Verbeek (2006), who draw on Latour in discussing designed artefacts as ‘materialised morality.’ Within these overarching ethical framings, several more specific topics have been explored. Design education, for example, features prominently, both as the venue for studying and reflecting on design ethics (e.g., Findeli, 1994) and as the focus of the ‘discipline specific’ ethics that designers must master (e.g., Donahue, 2004). Other topics include concrete tools and models that may serve designers (e.g., D’Anjou, 2010; Gauthier, 2006). Despite the fact that ethics has remained a topic for design research for decades, scepticism remains in terms of the progress made. Fry (2004) argued that ethics in design remains a “stranded debate” because of still infant cultures of design, and Chan (2018) finds that ethics in design is underdeveloped, calling for a revitalization. Devon & Van der Poel (2004) argue that too much attention has been given to individualistic accounts of ethics and suggest focusing on social ethics. Despite persistent issues, there is agreement across much of the literature that ethics plays a central role in design and that there is a need to further our understanding of ethics in design.

Regarding the academic disciplines more specifically concerned with designing and conceptualising digital technology, there has been a growing interest in ethics in recent years within several areas. Within the broad field of HCI, ethics has a long history and can be traced through writings going back to Wiener’s (1950) work on the ethical aspects of computerised automation. In a more recent contribution, Shilton (2018) provides a thorough account of the developments, history, and standing issues related to ethics in HCI. Codesign and participatory design also have a long-standing history of engaging with ethical issues. Steen (2013) argued that codesign and related approaches such as human-centered design are inherently ethical processes, and Simonsen and Robertson (2012) devote an entire chapter of their handbook to the ethics of participatory design. The renewed interest in ethics within these areas has sparked a number of recently published reviews (e.g., Van Mechelen et al. 2020; Nunes Vilaza et al. 2022) that focus on ethics in interaction design and HCI, and call for increased attention to the issue.

Related to the questions of ethics in design practice addressed in this paper, a more recent strand of research is particularly relevant. This strand has emerged around HCI, where a series of contributions have begun to explore how ethics plays out in commercial practice, with a common denominator being increased attention to ‘situational ethics’ (Munteanu et al., 2015). A number of issues have fuelled this strand of research. Frauenberger et al. (2017) argue that ethics is too often interpreted as a static and formalised process and propose ‘in-action ethics’ as a framework for linking anticipatory ethics to practice in design and HCI, while Grey et al. (2019) similarly call for work that explores ‘ethics on the ground,’ The main questions explored within this strand of research relate to how practitioners experience ethics in their everyday work and the kinds of practices that give rise to ethical deliberation. To balance formalised and static approaches to ethics in design, Frauenberger et al. (2017) propose the concept of ‘ethos’ to describe the emerging moral commitment that evolves as design projects progress. The evolving nature of ethics in practice is also addressed by Spiel et al. (2018), who explore the ‘micro-ethics’ of doing participatory design. In particular, Spiel et al. attend to the need to rely on multiple moral frames of reference and the pervasiveness of situated ethical judgments in design work that are often overlooked. The attention to the situated nature of ethics is echoed by Shilton (2013), who identifies particular practices that serve as ‘values levers’ capable of spurring discussions on ethics and supporting practitioners in ethical deliberation.

Moving closer to the practice of commercial design, a series of studies have recently begun to study ethics as it plays out among designers of digital technologies in complex organisational settings. The central issues pursued in this work include exploring the practices and factors that mediate and give rise to ethical deliberation. Rivard et al. (2021) explore healthcare innovators’ reasoning about care and responsibility, and the tensions they experience when facing conflicting responsibilities. From the perspective of UX practices, Gray et al. (2019) present a study of ethical mediation in UX practices and identify personal and organisational factors that mediate ethical awareness. In two subsequent studies, Chivukula et al. (2020, 2021) explore how dimensions of design complexity, in different ways, influence ethical outcomes and the identity claims that underlie ethical awareness among UX practitioners. Continuing the focus on how ethical concerns play out in collaborative settings, Watkins et al. (2020) identify the kinds of interactions that lead to how ethical concerns among individual designers are negotiated in an organisational setting.

As demonstrated above, there is an emerging literature on design ethics and an increased attention to ethics among practitioners developing technology. However, the contributions are still relatively few, and our knowledge of how ethics plays out in practice remains limited. In this paper, we extend the concern for studying ethics as it plays out in practice and on its own terms. In particular, we build on the work of Chivukula et al. (2020) and Shilton (2013), focusing on the material and organisational circumstances in which ethics unfolds, and the practices that spur ethical deliberation. In relation to this work, our study focuses specifically on how practicing designers understand ethics as part of their practice, the concepts they use to articulate this understanding, and how they deal with ethics at different times in their practice. Whereas several of the studies presented above are based on results on research with UX practitioners working in an organisational context, our study focuses on designers working in design consultancy. A key feature of design consultancy is that projects are acquired via external clients. This means that the participants in this study often engage with new clients and in new business areas, highlighting issues that surround providing services in which there are potentially conflicting agendas between various parties.

Method

The study presented in this paper involves interviews with 11 design practitioners, and explores how they understand and deal with ethics in their practice. In this section we present our method in terms of data collection, interview protocol, analysis, and limitations.

Data Collection

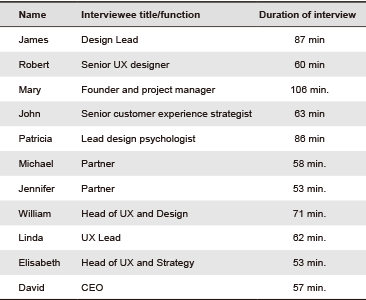

11 semi-structured interviews were set up with industry professionals across Denmark (five women and six men, see Table 1). The interviewees were recruited based on two criteria. First, to focus on the issue of design and ethics as they relate to digital technology, we chose design professionals who work for consultancies that are primarily occupied with the design of digital products and services. This meant that we did not include designers working in companies that primarily produce other services or products, such as banks or medical companies. This is not to suggest that ethics is not relevant in these fields, but including these would potentially introduce additional ethical concerns related to the organisations’ main activities. Second, to understand the range of issues related to ethics in design, we strived to recruit professionals at all levels of the organisation, from designers working on graphics to design managers dealing with strategic decisions. Despite different functions, we only included people who, in their own judgment, worked directly with design. The consultancies included in this study range in size from medium (30-99 employees) to small (less than 10 employees).

Table 1. The 11 interviewees, their title/function and duration of interviews. All names of interviewees have been anonymised.

Interview Protocol

The interviews were conducted by two of the authors, and followed a semi-structured protocol where interviewees were asked to share their understanding of design ethics, how this phenomenon was present in their work, and to provide concrete examples from their practice. Prior to the interviews, the interviewees were informed about the topic of the interview and asked to bring along examples of processes or projects where ethics had played a prominent role. In line with the research focus on exploring how practitioners understand and deal with ethics in practice, the questions posed for the interviewees ranged from direct questions asking them to reflect on what they understood the term ‘ethics’ in design to mean, to questions related to their prior experiences, that is, the examples they provided in which they believed ethical issues had emerged. Most interviews began with broad questions asking participants to describe their job and their everyday work tasks. Following this opening, the interviewees were asked to provide their initial thoughts on ethics in relation to their work. For the remainder of the interviews, the focus was on the cases and examples that the interviewees had brought, probing for further details and reflections on how ethical issues were present in particular situations. Following the semi-structured format, interviewees were given time and space to diverge from the immediate topic as long as the interviewer sensed that the overall conversation remained relevant. Prior to the interviews, the interviewees were informed of the study format and provided with the option of opting out at any time and having their data deleted should they regret their participation. The interviews lasted between 53 and 106 min. and were all conducted at the interviewees’ place of work. The interviews were recorded and transcribed for analysis using the Dedoose™ software.

Data Analysis

A thematic analysis was conducted which followed the six phases described by Braun and Clarke (2006). First, all authors read through the interviews to get a sense of the material. During this process, a set of a priori codes was initially applied as a means for authors to reflect on and discuss the nature of the material as they read and to determine how the content of the interviews connected to the research questions. These initial codes, which were derived from the overarching research question, were: Participants’ understanding of ethics, the meaning of ethics in practice, and how, when and where ethical issues are dealt with. As such, the initial phase of the analysis employed a hybrid strategy (Crabtree & Miller 1999; Fereday & Muir-Cochrane 2006), where initial codes served as orienting concepts allowing researchers to reflect on the material to be developed and refined in subsequent stages using the inductive coding strategy (Braun and Clarke 2006). In the second step, an initial set of codes (e.g., tools and procedures used, conflicts, ethical concepts and references, personal ethics, client ethics, etc.) was developed by inductively identifying salient features of the data. This process required several iterations between the authors where parts of the material were coded by all authors in collaboration to test whether the codes were adequate, as well as to ensure a uniform coding practice. This process continued until codes were saturated and a uniform coding practice was established. The remainder of the interviews were then divided between the authors for final coding. In the third and fourth step, cross-cutting themes were collectively developed to capture recurring patterns of meaning across the data. Themes were developed through a process of sorting codes and iteratively formulating, reviewing, and modifying potential themes to ensure that they adequately related to the data. This process resulted in six themes. In the fifth and sixth step, the themes were described and refined, and the final report was produced (see Results).

Limitations

The study was conducted in Denmark, and hence it is likely to reflect Denmark’s design and general working culture. In particular, Denmark has a strong tradition of flat organisational structures and directly involving employees in decision processes. This may impact the extent to which the results in this paper would be corroborated elsewhere. Also, an inherent limitation of the interview methodology is that it only captures interviewees’ thoughts, opinions, and reflections on ethics. Participant observations or the application of other methods could reveal additional aspects and insights.

Results

In this section we present the six themes that emerged from our analysis of the interviewees’ understanding of what ethics is and how it is dealt with. To communicate how the themes relate to the overarching research question, the six themes identified are structured under three headings that address the following questions: How is ethics understood? Where and when is ethics dealt with? How are ethical judgments made?

How is Ethics Understood?

Three themes emerging from the analysis speak particularly to the question of how ethics is understood by the participants. The first theme concerns their understanding of the nature and scope of ethics in design; the second concerns the use of metaphors and concepts to articulate ethics; and the third theme concerns the personal and collective levels of ethics.

Theme1: Ethics as Responsibility and Impact

The interviewees generally provided rich accounts of the ethical issues they face in their practice, yet their reports contain no concise definition of what ethics is in design practice. The most frequent account provided by the interviewees describes ethics in terms of a responsibility for the things they put into the world through design and the consequences these things have. John describes this as follows:

Every single time we create changes, it is an ethical activity. That is, design is an ethical activity, and because of this, we need to consider what effect the things we create will have, or how it will influence the world, the people that are in contact with the systems we design.

Patricia specifically talks about ethics both in terms of the impact that things will presumably have, but also in terms of being clear about the risks that it involves. Several interviewees link the issue of product consequences to the notion of ‘purpose.’ Patricia explains ethics as paying attention to

That there is a greater purpose, and what we are doing will affect both individuals that use it, but also the employees that will work with it.

Similarly, Mary explains:

We often talk, not so much about ethics, but at least about values and what the purpose is, with what we are about to start.

While the predominant understanding of ethics expressed by the interviewees relates to the consequences of products and design process, other conceptions are also voiced. David and Michael talk about ethics in terms of the obligations and values of the designers. David explains that “it’s both about an obligation but it is also a gift” and Michael suggests that “in reality, it’s all about the values you base your decisions on, when it comes to designing products and services.” Mary extends the concern for responsibility by linking ethics to the way designers nudge people towards particular behaviours:

I think ethics is very much about whether you want to nudge people to do something. There is something in that we have so many tools to make people look towards the right place, click the right place, and maybe buy the right product.

Theme 2: Metaphors and Articulations

The second theme concerning the nature of ethics relates to some of the interviewees’ frequent use of metaphors and colloquial terms to describe ethics and how ethics is articulated in relation to existing ideas and principles.

The most frequently used metaphor is that of ‘an ethical compass’ (four of the interviewees use this term). Though this term has been used in the existing literature, the interviewees’ use appears to be purely colloquial. James mentions it in relation to the shared understanding within the company:

It may sound vague, but I really think that with the way it [the consultancy] is and the way we [the employees, ed.] are, I think it’s an okay compass actually to work with.

Mary uses the metaphor in a more personal sense, explaining “as a designer I prefer not to have restrictions. I want to allow myself to think wild, and let my ethical compass control me.” Other metaphors are also found among the interviewees. For example, Michael uses the term ‘footprint’ as a metaphor for how he understands design ethics, he explains “I think that it’s [ethics] about how big a footprint you have in what you do.”

I addition to the use of metaphors, the interviewees often articulate their understanding of ethics through a series of concepts, frameworks, or principles. These articulations stretch from UN sustainable development goals (SDG) and inclusivity to CSR and GDPR. The concepts are obviously different in nature and scope, but they are all used by the interviewees as concrete ways of articulating what ethics is, how it manifests in their work, and as concepts that provide them with direction in their design work. In some cases, the interviewees speak of these as ethical standards or even guidelines, while at other times they are used to explain the interviewee’s own conception of ethics. Mary says:

I’m also thinking that with the UN sustainable development goals and things like that there is also some sustainability and some ethics in terms of what one should do and how we as designers can do the right things.

Here, the SDGs are understood as an articulation of ethics to guide design. The same appears to be the case in the way the interviewees use GDPR.

In other instances, interviewees use other concepts to describe what they consider to be different aspects or issues that are related to ethics. The most prominent examples include issues related to equality, gender, accessibility, and inclusion. As an example, Jennifer, a partner, explains that they had discussed whether it would be “proper to put an office in a country where women do not have the same rights as men,” were it commercially attractive.

Despite the fact that the interviewees do provide both interesting and rich answers to the question of what ethics means to them, the interviews contain no concise definitions. Nor do they contain references to established theories or conceptions about ethics. A few of the interviewees do note that they believe that ethics can, in fact, be regarded as an integral part of design. David suggests that ethics is part of design because design builds on “a humanistic tradition about believing that you can design your way to, in reality, something that is better than what you came from.” Despite this, David ends the interview by capturing what is generally reported across the interviews, namely that ethics is considered very important, but difficult to grasp and deal with in practice:

Everybody wants to, you know, from the board room to management wants to do something [about ethics] but it’s like a wet bar of soap, how the hell are we going to start, you know, what does it actually mean. It’s difficult, it impacts all kinds of things.

Theme 3: Personal, Collective, and Client Ethics

A recurring theme among the interviewees is the relationship between the personal ethics of the individual designer, the ethics of the consultancy, and that of the client. The ethics of the clients is discussed in all of the interviews as a fundamental premise of working in design consultancy, where new clients from different business areas are engaged with on a regular basis. Not only does this prompt reflection on the kinds of clients and agendas that the participants want to engage with, it also acts as the backdrop from which the participants articulate their personal ethics. Indeed, the idea of personal ethics pervades most of the interviews and is articulated as beliefs and values that are tied to individual preferences and experiences. The examples provided include religious beliefs and beliefs about promoting sustainability. Ethics is, however, also more generally articulated as the personal responsibility of the designer. Linda explains:

It’s [ethics] the way you act as a human being, I would say, the way you enter into things [engagements with others].

Several of the interviewees also use the notion of ‘being a decent person’ and having the ‘character’ to act in a decent manner. In other instances, ethics is also mentioned as a motivator for the interviewees. Robert explains:

I thought that it was nice [when he visited a client] that there was an ethically responsible mission, I think it gave me something.

As evidenced by these quotes, personal ethics is positioned in relation to the agendas of the clients, which play a central role in the everyday work.

While ethics is articulated as a personal issue, the interviewees also explain that some overarching ethical decisions are taken by management, such as decisions about which clients to engage with and how. The issue of management ethics and personal ethics is frequently addressed. In some instances, clear distinctions are made between ethical decisions made by management versus those informed by personal ethics. Patricia explains: “So there is the company’s position [whether to take on a project] and then there is sort of the personal position.” Mary emphasises that their consultancy’s ethical approach is primarily based on individuals:

I think ethics at [consultancy name] is relatively individual-based. We don’t have an ethical code or anything explicit about ethics. It lies very much at the individual.

In other cases, the distinction between personal ethics and that of the consultancy is less clear.

Despite the distinction between the personal and the organisational, the interviewees’ responses are also pervaded by the use of a generic ‘we,’ as exemplified by John: “so ethics is the first step; that we actually relate to what it is we want and, what kind of change do we want to create.” The collective ‘we,’ which is used on several occasions in the interviews, appears to refer to a consensus that has been reached within the particular consultancy. In the interviews it is however sometimes unclear what the generic ‘we’ refers to, whether it includes people on a particular project, a particular group, the entire consultancy, or even the clients themselves.

Where and When is Ethics Dealt With?

Theme 4: Important Decisions Are Made Before or in the Beginning of Projects

In terms of the ‘where’ and ‘when’ of addressing ethical issues, the recurring theme is that much is decided during the initial stages of a project or before a project is started. Several interviewees mention that there are projects and clients that they will categorically not engage with. These are typically defined by a specific industry or business area and the examples most often given are the tobacco or weapons industry. Jennifer explains “We will not work for the tobacco industry, we will not work for the weapons industry, those are some basic low-hanging fruits.” David elaborates:

if a tobacco company came to us and needed a new platform and a re-branding (...) professionally a super exciting task, but I don’t want to bring more cigarettes into the world or motivate more people to smoke.

Jennifer specifically links the very notion of ethics to the choice of clients and projects, suggesting that practicing ethics in design is about “how you accomplish a task, but also very much in those tasks you decide not to do.”

In other instances, grey areas are discussed, such as online betting firms or organizations that, from the perspective of the interviewees, do not have sufficiently high environmental standards. Mary provides a lengthy discussion of their engagement with a betting firm, arguing that, on the one hand, there was hesitation due to the possibility of making people addicted to betting, and yet they did want to improve the betting experience and make it more social and enjoyable.

Once collaborations with clients have been started, several interviewees report that much is decided in the initial meetings with clients. Robert addresses the kick-off session with clients by stating, “In terms of ethics, a lot is going on here, because we frame the rest of the process.” Mary explains that initial meetings often include the formulation of a shared vision and a discussion of the central values of the project. Beyond the initial dialogue and decisions about the kinds of clients to engage with, the interviewees also report that ethics is dealt with throughout the process. James explains that as the process progresses there is a move from ‘macro ethics’ in the beginning, where purpose and overarching issues are discussed, towards ‘micro ethics’ as the product takes form. The examples of ethical decisions and dilemmas cover a range of arenas. Besides the most prevalent theme (design decisions related to the product and their effects) mentioned earlier, Jennifer argues that ethics also plays a role in the recruitment of new employees, in terms of establishing their values and their overall approach to design. It is also noted that ethics plays a role when conducting user tests as they relate to informing users of the purpose and ensuring that the experience is meaningful for them.

Generally speaking, the picture painted by the interviewees is that of a process where the broad and overarching decisions are made in the beginning, and as the projects progress, ethical issues become more narrow and micro level. Initial macro issues include which clients and business areas to engage with in the first place and, as the project progresses, how projects are framed, including the values that are decided upon in initial meetings with clients. In the later stages of a project, the ethical decisions are perceived to occur more frequently on a micro level.

How Are Ethical Judgments Made?

In terms of how ethical judgments are made, two primary themes emerge: namely, 1) the prevalence of ad dialogues, and 2) the lack of methods or tools. These are often articulated within the overarching dilemma of both acting in an ethical manner while also acknowledging that the consultancy needs to bring in business to make money.

Theme 5: Dialogues and Conflict in Dealing with Ethics

Several of the interviewees refer to ongoing dialogue concerning ethical issues and conflicts within the consultancy as the main way of addressing ethics. There is a clear pattern in the interviews that while some ethical decisions regarding which clients and projects to take on are decided by management, the ongoing ethical dialogues are ad hoc with no formal structure. The interviewees provide several examples of the dilemmas and potential conflicts that emerge as designers are charged with pursuing a particular client agenda and the more or less explicit ethics that this entails. Robert explains:

It can be contradictory to have a client who wants to maximize something and you are personally thinking that I don’t really want to do that. But you are put on a project to do a job and you can’t really spoil that. Then you should become an activist and that would probably have some personal consequences.

In terms of how conflicts between the ethics of designers, consultancies, and clients are dealt with, the reports from the interviewees contain several approaches. Robert explains that a lot of the work in deciding what ‘we’ believe, is done ‘organically’ during their everyday work. Most interviewees report that there are certain industries that they, as a bureau or personally, will not work with. Several of the interviewees report instances where there had been a conflict between a particular designer and a client (typically because of the industry in which the client operates). Patricia explains how a situation was resolved by taking the designer off the project:

I have experienced a colleague who was a vegetarian who said that ‘I can’t work on this project.’ And this is totally accepted [by the consultancy]. So that is the position of the consultancy and there is then the personal position.

In the other examples, conflicts between individual ethics and the client were resolved through dialogue and negotiations. Several interviewees explain that their clients and their businesses are often discussed as part of ongoing dialogues within the consultancy. James explains that in several cases, management would specifically seek the advice of employees in cases where the project or client was perceived to be in an ethically grey area and they wanted to make a decision about which ethical stance to take.

Also, in the dialogue with clients, several of the interviewees provide accounts of situations where they tried to sway or influence clients towards certain directions that align with identified user needs. Mary provides an illustrative description of the dilemmas:

So the client is paying for the product but the users seem to want something else [than the product favoured by clients] that goes in another direction. So, there is typically some discussion about who to please, and also, how do we convince the client to choose the right thing.

None of the interviewees included in this study reported having formalised ways of dealing with ethical issues and concerns at their workplace.

Theme 6: (No) Methods and Tools

The final theme to clearly emerge is that the interviewees generally do not use methods, tools, or conceptual frameworks when engaging with ethical issues. This is reported by all interviewees. When asked directly about tools, techniques, or frameworks, James confirms that none of these are a factor:

No. It’s not like I think we have a completely streamlined process for it [dealing with ethics] or that we have a framework (...) No, I think it comes down to our own gut feeling.

Other interviewees add that in many cases ethical judgments are made implicitly through the choices that each person makes, whether it be in the backend of the product or in the user interface. For this reason, many ethical issues are resolved without being brought to the attention of others. When ethical judgments are made explicitly, decisions are made through dialogues that are often ad hoc or emerge as the process and product develop. Several interviewees report that the dialogue is both horizontal (among employees) and vertical (involving management). To the extent that the interviewees address the issue of tools and frameworks, the interviewees refer to the articulations addressed earlier, such as inclusion, sustainability, and GDPR as the points of reference for dealing with ethical issues. Throughout the interviews, these concepts are used both as the standards to which interviewees would like to hold themselves and as a way of defining the very idea of ethics.

Although the absence of methods is striking, is does seem that the continuous dialogue taking place within the consultancies and among employees can in itself be regarded as a strategy or even a methodology for dealing with ethics. While less formalised, it is clear that interviewees are very articulate and reflective about the kinds of engagements they want to pursue, both in terms of their personal ethics as well as how the consultancy as a collective is positioned.

Discussion

The six themes presented in the preceding sections contribute to the understanding of how practitioners understand and deal with ethics. Together, they shed light on the nuances of how design practitioners articulate the concept itself, where and when it is dealt with, and how ethical judgments are made. Related to the emerging literature introduced in the first part of the paper, which seeks to study ethics on its own terms, this study further demonstrates how ethics is articulated by practitioners and the various levels of ethical concerns they encounter. Below, we address two areas in which these results extend existing work and provide avenues for future work.

Concepts for Articulating Ethics in the Process

Looking at how interviewees understand ethics in relation to their practice, the consequentialist view of ethics, articulated as a concern about the effects of the products that are put into the world, is the most pronounced. Other conceptions are, however, also visible, as interviewees expressed issues that are closely tied to the virtues of the designer and to individual conceptions of what is right and wrong. From the results it is significant that the accounts provided by individual interviewees often contain two or more conceptions of ethics, not standing in opposition to one another, but rather as co-existing perspectives on what they conceive ethics to mean. This echoes the situated and emergent understanding of ethics presented by Frauenberger et al. (2017), particularly the idea of flexibly adopting multiple moral frames in practice, as propounded by Spiel et al. (2018).

Another noteworthy aspect of the results presented in this study is the way in which practitioners articulate their understanding of ethics through the use of concepts such as inclusivity, sustainability, and SDGs. While these concepts are different in nature, the ways in which they are used by the interviewees to articulate ethics share at least two common features. First, the way concepts are used align primarily with consequentialist conceptions of ethics; they speak to the potential consequences of designed products and the degree to which designers are responsible. Second, the concepts share a level of abstraction between general worldviews or theory and concrete recommendations. They are specific enough to support interviewees when articulating a set of values or a core concern, yet general enough to have a wider application than a typical heuristic or a design principle. In the way they are used by the interviewees, they are similar to the idea of ´strong concepts’ (Höök & Löwgren, 2012), understood as intermediate-level knowledge that is generative in terms of grasping ethics in design. However, the concepts used by the interviewees relate almost exclusively to the consequences of the products they produce for clients, rather than how ethics is dealt with in the process. A notable exception is the idea of the ‘ethical compass’ which is used to explain how ethical issues are dealt with by individuals. In the interest of extending recent work focusing on the emergent nature of ethics, and how ethical concerns are dealt with in practice, we suggest that a fruitful avenue for future work is to explore strong concepts that help practitioners reflect on how ethics is addressed in through the process. In existing work, the concept of ‘values levers’ (Shilton, 2013) is arguably a good example of a concept that orients practitioners to the kinds of practices that give rise to ethical deliberation. This concept speaks to the processes and practices that prompt ethical reflection rather than merely considering the direct consequences of products. Based on the present study, we envision similar concepts might be developed to address the different kinds of ethical issues that practitioners deal with, ranging from macro-ethical concerns about clients and industries to the micro-ethical concerns that arise as a process progresses. Given that work presented in recent years has yielded insights into the complex interplay between individual designers, organisational factors, and ethical principles (Grey et al., 2019; Chivukula et al., 2020), there is an emergent knowledge base from which to develop such strong concepts.

Levels of Ethical Engagement

The interviewees reported that ethical issues are dealt with differently in different parts of the process; ‘macro’ ethics most often appears in the early stages of the process while ‘micro’ ethics more often arises through ongoing ad hoc dialogues in the later parts. In contrast to previous work, the participants recruited for this study are exclusively from design consultancies and therefore reflection on the engagement with new clients pervades the interviews. It also means that issues such as the positionality of UX in the enterprise and relationships to other departments, which has been reported in prior work (Chivukula et al., 2020), do not play a prominent role in this material. It is, however, evident that in the interviews conducted for this study, there is a notable correlation between the span from macro to micro ethics and the temporal progression of the design process. Before engaging with a client, practitioners report that they may have general concerns about which industries or partners they want to engage with. As projects begin, initial meetings with clients determine the broader values and premises of the project, and as the project progresses, the interviewees report that ethical issues take on a narrower micro character. While the span from macro to micro ethics has, to some extent, been addressed in the literature (e.g., Spiel et al., 2018), this in itself represents an area where more research is necessary to better understand the different levels of ethical engagement and how it affects the framing of the process. Moreover, we suggest it would be relevant to further explore the correlation between the kinds of design activities taking place at different times of the design process and the nature of ethical concerns they might entail. Shilton (2013) does, to some extent, address this through the concept of values levers, but our suggestion here is to explore how different design specific activities and tools, such as workshops, design sprints, sketching, and prototyping may give rise to different kinds of ethical concerns. Similar to the way that several design models have described divergence, convergence, and the movement from the general and abstract to the particular (e.g., Löwgren & Stolterman, 2004; Buxton, 2010), we suggest exploring how the scope of ethical issues develops along the lines of these design activities as processes progress.

Exchanges Between Research and Practice

Returning to the issue raised in the beginning of this paper suggesting the need for more exchange between research and practice, the two issues discussed above speak directly to avenues for future work that could potentially create this exchange. Another area in which we suggest potential for future work—and indeed for spurring exchange—relates to research methods and the nature of the studies involving academia and practice. Much of the literature cited in this paper which studies ethics in practice (this paper included), uses interview formats or ethnographic studies as the main form of inquiry. While these are, of course, recognized approaches, and have indeed proven valuable, there is arguably room for other types of design research that approach the issues from a constructive and experimental perspective. For example, collaborative and participatory approaches, where future users are directly involved in research activities, are common in design research, and it may be fruitful to explore how we might co-design design ethics in collaboration with practitioners. Not only may participatory approaches yield concepts and ideas that are attuned to the people who deal with design ethics in practice, but they could also provide a venue for mutual learning between research and practice. Participatory design in particular emphasizes the mutual learning (Simonsen & Robertson, 2013) that emerges from participation as an important outcome, where researchers learn about the reality of practitioners who, in turn, are provided with the means for reflecting on and developing their own practice. Moreover, constructive and experimental approaches to design research could also present a promising path forward. As noted earlier, there is a growing body of knowledge about ethics in practice that might provide a platform for this research. We invite researchers to explore novel forms of research engagements that may advance the area of design ethics in practice.

Conclusion

In this paper we have reported an interview study which includes 11 design practitioners exploring how they understand and deal with ethics as part of their practice. Our analysis materialised in six themes that contribute to our understanding of how practitioners define and articulate the concept of ethics, and how they draw on concepts such as GDPR, ‘inclusivity,’ and ‘sustainability’ to capture the nature of ethics. Moreover, the results demonstrate how practitioners navigate their personal ethics, the ethics of the consultancy, and that of their client. In their accounts, the interviewees reported that they do not use formal methods or procedures for dealing with ethical issues, but often rely on internal dialogues with colleagues and management and external activities with clients. Our results provide avenues for future research related to the kinds of concepts used to articulate and address ethical concerns in the design process and how different design activities present different levels of ethical engagement.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of this study for taking the time to share their thoughts and reflections on ethics in their practice.

References

- Aicher, O. (2015). The world as design. John Wiley & Sons.

- Akama, Y. (2012). A ‘way of being’ in design: zen and the art of being a human-centred practitioner. Design Philosophy Papers, 10(1), 63-80. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279312X13968781797634

- Bousbaci, R., & Findeli, A. (2005). More acting and less making: A place for ethics in architecture’s epistemology. Design Philosophy Papers, 3(4), 245-264. https://doi.org/10.2752/144871305X13966254124996

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buxton, B. (2010). Sketching user experiences: Getting the design right and the right design. Morgan Kaufmann. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374037-3.X5043-3

- Chan, J. K. (2018). Design ethics: Reflecting on the ethical dimensions of technology, sustainability, and responsibility in the anthropocene. Design Studies, 54, 184-200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2017.09.005

- Chivukula, S. S., Watkins, C. R., Manocha, R., Chen, J., & Gray, C. M. (2020). Dimensions of UX practice that shape ethical awareness. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1-13). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376459

- Chivukula, S. S., Hasib, A., Li, Z., Chen, J., & Gray, C. M. (2021). Identity claims that underlie ethical awareness and action. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1-13). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445375

- Crabtree, B. F., & Miller, W. L. (1999). Doing qualitative research. Sage.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

- d’Anjou, P. (2010). Beyond duty and virtue in design ethics. Design Issues, 26(1), 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1162/desi.2010.26.1.95

- Devon, R., & Van de Poel, I. (2004). Design ethics: The social ethics paradigm. International Journal of Engineering Education, 20(3), 461-469.

- Donahue, S. (2004). Discipline specific ethics. Design Philosophy Papers, 2(2), 95-101. https://doi.org/10.2752/144871304X13966215067877

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Findeli, A. (1994). Ethics, aesthetics, and design. Design Issues, 10(2), 49-68. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511628

- Frauenberger, C., Rauhala, M., & Fitzpatrick, G. (2017). In-action ethics. Interacting with Computers, 29(2), 220-236. https://doi.org/10.1093/iwc/iww024

- Fry, T. (2004). The voice of sustainment: Design ethics as futuring. Design Philosophy Papers, 2(2), 145-156. https://doi.org/10.2752/144871304X13966215068038

- Fry, T., & Dilnot, C. (2003). Manifesto for redirective design: Hot debate. Design Philosophy Papers, 1(2), 95-103. https://doi.org/10.2752/144871303X13965299301795

- Gauthier, P. (2006). Not good enough? A response to Wolfgang Jonas: A special moral code for design? Design Philosophy Papers, 4(4), 247-254. https://doi.org/10.2752/144871306X13966268131956

- Gray, C. M., & Chivukula, S. S. (2019). Ethical mediation in UX practice. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1-11). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300408

- Höök, K., & Löwgren, J. (2012). Strong concepts: Intermediate-level knowledge in interaction design research. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 19(3), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1145/2362364.2362371

- Johansson-Sköldberg, U., Woodilla, J., & Çetinkaya, M. (2013). Design thinking: Past, present and possible futures. Creativity and Innovation Management, 22(2), 121-146. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12023

- Jonas, W. (2006). A special moral code for design? Design Philosophy Papers, 4(2), 117-132. https://doi.org/10.2752/144871306X13966268131596

- Gropius, W. (1919). Manifesto of the Staatliches Bauhaus. Retrieved January 9, 2020, from https://bauhausmanifesto.com

- Löwgren, J., & Stolterman, E. (2004). Thoughtful interaction design: A design perspective on information technology. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/6814.001.0001

- Manzini, E. (1999). Strategic design for sustainability: Towards a new mix of products and services. In Proceedings of the 1st international symposium on environmentally conscious design and inverse manufacturing (pp. 434-437). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ECODIM.1999.747651

- Mitcham, C. (1995). Ethics into design. In R. Buchanan & V. Margolin (Ed.), Discovering design: Explorations in design studies (pp. 173-189). The University of Chicago Press.

- Munteanu, C., Molyneaux, H., Moncur, W., Romero, M., O’Donnell, S., & Vines, J. (2015). Situational ethics: Re-thinking approaches to formal ethics requirements for human-computer interaction. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 105-114). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702481

- Morris, W. (2002). News from Nowhere. Broadview Literary Press.

- Nunes Vilaza, G., Doherty, K., McCashin, D., Coyle, D., Bardram, J., & Barry, M. (2022). A scoping review of ethics across SIGCHI. In Proceedings of the conference on designing interactive systems (pp. 137-154). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3532106.3533511

- O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Broadway Books.

- Papanek, V. (1972). Design for the real world. Thames and Hudson.

- Rivard, L., Lehoux, P., & Hagemeister, N. (2021). Articulating care and responsibility in design: A study on the reasoning processes guiding health innovators’ ‘care-making’ practices. Design Studies, 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2020.100986

- Shilton, K. (2013). Values levers: Building ethics into design. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 38(3), 374-397. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243912436985

- Shilton, K. (2018). Values and ethics in human-computer interaction. Foundations and Trends in Human–Computer Interaction, 12(2), 107-171. https://doi.org/10.1561/1100000073

- Simonsen, J., & Robertson, T. (Eds.). (2012). Routledge international handbook of participatory design. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203108543

- Spiel, K., Brulé, E., Frauenberger, C., Bailly, G., & Fitzpatrick, G. (2018). Micro-ethics for participatory design with marginalised children. In Proceedings of the 15th conference on participatory design (Vol. 1, pp. 1-12). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3210586.3210603

- Steen, M. (2012). Human-centered design as a fragile encounter. Design Issues, 28(1), 72-80. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00125

- Steen, M. (2013). Co-design as a process of joint inquiry and imagination. Design Issues, 29(2), 16-28. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00207

- Stolterman, E. (2021). The challenge of improving designing. International Journal of Design, 15(1), 65-74.

- Thackara, J. (2015). How to thrive in the next economy. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Tonkinwise, C. (2004). Ethics by Design, or the Ethos of Things. Design Philosophy Papers, 2(2), 129-144. https://doi.org/10.2752/144871304X13966215067994

- Van Mechelen, M., Baykal, G. E., Dindler, C., Eriksson, E., & Iversen, O. S. (2020). 18 years of ethics in child-computer interaction research: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the conference on interaction design and children (pp. 161-183). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3392063.3394407

- Verbeek, P. P. (2006). Materializing morality: Design ethics and technological mediation. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 31(3), 361-380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243905285847

- Watkins, C. R., Gray, C. M., Toombs, A. L., & Parsons, P. (2020). Tensions in enacting a design philosophy in UX practice. In Proceedings of the conference on designing interactive systems (pp. 2107-2118). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3357236.3395505

- Wiener, N. (1950). The human use of human beings: Cybernetics and society. Houghton Mifflin.

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Profile books.