Guerrilla Wars in Everyday Public Spaces:

Reflections and Inspirations for Designers

Kin Wai Michael Siu

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

Corresponding Author: m.siu@polyu.edu.hk

In recent years, many governments have tended to take a rational and development-oriented approach to planning, designing and managing city spaces. Some sociologists, however, have started to criticize this approach, and have begun to advocate instead the importance of taking into consideration the everyday lives of ordinary people. These sociologists offer us a new perspective for examining how “city users” are tactically living in their cities. This perspective may not be accepted by all, and may have quite a lot of practical limitations; nevertheless, it at least offers today’s designers as well as policymakers and other professionals some reflections and inspirations for further exploration and discussion. Through a theoretical review of how theorists and sociologists see city space and its order from different perspectives, and through empirical longitudinal studies done on three Hong Kong market streets, this article attempts to ascertain whether the inhabitants of a city-city users-are “tactical practitioners.” The article then explores the role of city users and their interactions with the spaces in which they are living, and offers advice to designers who aim for more people-environment fit designs.

Keywords - Design, Everyday Life, Public Space, Strategy, Tactic, User Practice

Relevance to Design Practice - The results of this research offer designers a new perspective for examining how city users are tactically living in their cities. The results also suggest that designers should work continuously with city users to conduct investigations, and to plan, design, implement and maintain the quality of the urban environment.

Citation:Siu, K. W. M. (2007). Guerrilla wars in everyday public spaces: Reflections and inspirations for designers. International Journal of Design, 1(1),37-56.

Received November 10, 2006; Accepted January 19, 2007; Published March 30, 2007

Copyright: © 2007 Siu. Copyright for this article is retained by the author, with first publication rights granted to International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

Dr. Siu is an associate professor in the School of Design at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. He is a chartered engineer and chartered designer. He is now affiliated also with the Department of Architecture of the National University of Singapore as Visiting Scholar, in which capacity he is conducting a research project related to public space. He is a fellow of the Chartered Society of Designers, the Royal Society of Arts, the Royal Geographical Society, the Royal Society of Health, and the College of Preceptors. He has been a visiting professor at universities in China and South Korea. He was a Fulbright Scholar at MIT (2002-2003), and an academic visitor in the Engineering Design Centre of the University of Cambridge (2001). His research and design focus on both technological and social perspectives. He has been involved in a number of funded research and design projects related to street furniture and public facilities, and owns more than 30 design patents in the United States, the PRC and other Asian countries. His articles have appeared in various journals including the Journal of Engineering Design, Design Issues, Critical Planning, the Journal of Popular Culture, Popular Culture Review, Human Relations, and Harvard Asia Pacific Review.

Introduction

Governments in general claim and promise to plan and design inhabitable city spaces for people. However, as we review current city projects, it is not difficult to notice that quite a lot of governments have continuously set up strategies and plans, and sought authority through legislation, to not so much design as control city spaces. When undertaking urban development projects, governments generally follow the planning principles of administrators who adhere to the deliberate forms of operational rationalism and, as a consequence, tend to neglect the human factors. They see rational planning as an active force and the only proper means of directing the community towards the ideal of social harmony. Governments also generally follow the planning principles of developers who openly maximise profit.

On the other hand, in studies of the “sociology of everyday life,” sociologists such as Michel de Certeau, Henri Lefebvre, and Michel Maffesoli, point out that everyday life in modern society is organised according to a concerted programme, and that the urban setting is cybernetized. People’s everyday lives are embodied in the experience of a highly organised (or, programmed) society. These sociologists have conducted detailed studies on the everyday lives of common people (or, ordinary people), and offer designers as well as other professionals a new perspective from which to see everyday life and the responses of people to their programmed living environment.

To explore this alternative perspective of theorists and sociologists, besides a literature review, longitudinal studies have been conducted along several traditional market streets in Hong Kong. These studies, which began in the early 1990s, aim to provide an in-depth investigation into users’ practices in everyday public spaces, and to shed light on design issues that are relevant to these spaces and that will generate insights for further discussion and investigation. In addition, this study also aims to help the reader become more familiar with the phenomenon so that the findings can prompt further research questions on potentially related processes and outcomes.

Methods of Study

Case Studies

Considering the objectives of this research, an exploratory approach has been adopted for the longitudinal studies. This does not mean that descriptive and explanatory research elements are neglected. On the contrary, as suggested by Andranovich and Riposa (1993) and Yin (1993) in their discussions of design research, descriptive and explanatory research approaches have been applied where the studies call for some description of users’ everyday practices and where the collected data has some bearing on cause-effect relationships. Moreover, the studies described here are also expected to stimulate more descriptive and explanatory research projects in the future.

A case study approach has been adopted for the longitudinal studies undertaken in this research. As Merriam (1988) points out, “case study is an ideal design for understanding and interpreting observations of social phenomena. …case study is a design particularly suited to situations where it is impossible to separate the phenomenon’s variables from their context” (pp. 2, 10). Yin (1994) agrees with Merriam, pointing out that a “case study can investigate a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially [if] the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident” (p. 13). Yin clearly identifies in his numerous publications (1993, 1994) that case studies should not only be used in studying how innovations in urban services become “routinized,” but should also be applied to the investigation of urban phenomena (or contemporary events), especially when “the relevant behaviours cannot be/should not be manipulated” (1993, pp. 3, 5; 1994, p. 8). Furthermore, a case study is effective for investigating different cases in the ambiguous urban space. The use of a case study approach hence is a suitable strategy, since the studies’ core objective is understanding the ways users operate in public city spaces.

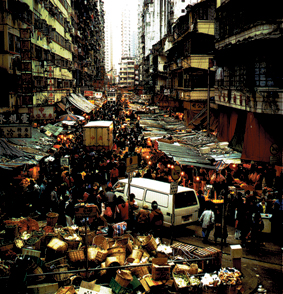

Three sites were selected as cases for in-depth study: Chun Yeung Street on Hong Kong Island, Fa Yuen Street in Kowloon, and Fu Shin Street in the New Territories. Each of these streets has a relatively long street-history in Hong Kong. Their present physical configurations are the result of continuous development over a period of at least seventy years, with one of the streets having a history of more than a hundred years. The streets are all located in areas of high population density. Although each street has its own background, development and physical configuration, they all reflect the local everyday life of Hong Kong people, in particular illustrating how people interact with the plans and designs of public spaces. The three streets not only act as links for circulation or as markets for selling and buying activities, but also consist of different types of public spaces for different uses. Today, these streets are the busiest streets in their own districts, and also the busiest streets in the whole territory of Hong Kong. In a way similar to many traditional market streets in Hong Kong, these three streets are full of human activity, providing ample opportunities for investigating how different individuals with different interests act diversely in public spaces.

|

Figure 1. Chun Yeung Street, North Point, Hong Kong Island. This street is located in a residential district. Most of the buildings were constructed right after World War II, whereas some new buildings for residential, commercial and hotel purposes have been constructed since the mid 1990s. It is a major transport link in the North Point area of Hong Kong and has a tram terminal at one end. Since the 1970s, the street has been full of temporary stalls selling daily necessities. (Source: Hong Kong Guide Book, 2000) |

|

Figure 2. Fa Yuen Street, Mong Kok, Kowloon. Besides being a district for residential purposes, Mong Kok is also a place that attracts young people for shopping and leisure activities. The street is located in the heart of the busy area of Kowloon. Several major transport links are located just beside the street. Thousands of people pass through the street every day. It is full of licensed temporary stalls that sell daily necessities, fruit, flowers, etc. Most of the surrounding buildings were constructed after the end of World War II, with some new high-rise buildings constructed after the late 1980s for commercial and residential purposes. (Source: Hong Kong Guide Book, 2000) |

|

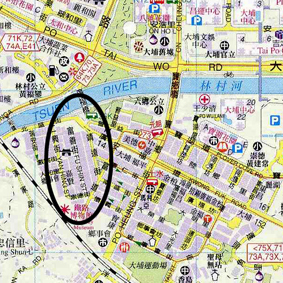

Figure 3. Fu Shin Street, Tai Po, New Territories. Tai Po is one of the oldest rural towns (and now a new town) in Hong Kong. Fu Shin Street is thus one of the oldest market streets in Hong Kong, with a history of more than one hundred years, and home to one of the oldest temples in Hong Kong, Man Mo Temple, which is located at the midpoint of the street. The street is a traditional market street that attracts thousands of local residents every day. The surrounding constructions and buildings are old, although due to new developments in Tai Po, some high-rise residential buildings have been constructed in the surrounding areas since the 1980s. (Source: Hong Kong Guide Book, 2000) |

The selection of these three streets does not imply that they have any particularly special constructions or characteristics that are different from other spaces in Hong Kong. In fact, these streets represent typical common public spaces in Hong Kong, having a certain degree of “publicness,” yet also affected by a variety of numerous controls and restrictions.

In addition to interviews with planners, designers, and representatives and officers of related departments and organisations, and a review of documents, field research has been conducted at selected sites on these three streets, chosen with regard to users’ everyday practices. Among a variety of field research techniques, the main ones employed have been field observation and direct interviews. These types of field research techniques have allowed the researchers to “tap attitudes and behaviours” (Andranovich and Riposa, 1993, p. 79) and to “seek descriptive information” and thus to “better understand people’s behaviour in the environment” (Sanoff, 1992, pp. 12, 31).

Observations

As Ng (1992) identifies, field observations give a more genuine picture of what it is like “in the field.” Observations can also “cover events in real time and cover context of event” (Yin, 1994, p. 80), and in addition enable the researcher to “better understand people’s behaviour in the environment …[as] it is a method of looking at action between people and their environment” (Sanoff, 1992, p. 33), and also help the observer to “find out what goes on in the subcultures or organizations being studied and to gain some insight into their operations (especially hidden aspects not easily recognized) and how they function” (Berger, 1998, p. 105). All of these advantages illustrate why observation was the primary data collection method used in the studies. In fact, the limitations of much recent design research (in environment design) are that they lack observation of the real-time practices of users. In a classic book by Albert Rutledge (1985) on park design, the author points out that the emphasis of field observations should be on “How to look?” and “What should be looked at?” Rutledge further comments that, most of the time, designers focus on human creations, and how these creations “match” the natural environment; and that sociologists tend to focus on individuals and how they interact with one another. So, Rutledge agrees with Roger Barker’s view, as expressed in his earlier publication, Ecological Psychology: Concepts and Methods for Studying the Environment of Human Behavior (1968), that, when observing human behaviour, focus should be on the “whole event.” This explains why the observations of the studies in this research have not only focused on the interactions of individuals with one another, but have also included the responses of the individuals to the environment. In short, in these studies, human beings and the environment have been considered as an indivisibly interactive “compound.”

In the studies, “unobtrusive direct observations” have been used to explore how users (called actors by some social researchers) operate in public spaces. In City: Recovering the Center (1988), Whyte explains the reasons for using this observation method:

We tried to do it unobtrusively and only rarely did we affect what we were studying. We were strongly motivated not to. Certain kinds of street people get violent if they think they are being spied upon. (p. 4)

In Integrating Programming, Evaluation and Participation in Design (1992), Sanoff also points out the advantages of this kind of observation method:

People may modify their action, however, if they realize they are being observed. Observing unobtrusively allows the study of people’s behavior without their realizing that their activities are important. (p. 33)

Direct Interviews

Although observations are the main method of primary data collection used during field research, interviews clearly offer an advantage in supplementary data collection. In the studies undertaken, the direct interviews have consisted mainly of requests for descriptions of everyday life in the public spaces and for information regarding the way the interviewees conceived of public spaces. “Casual conversations,” as suggested by Andranovich and Riposa (1993), have been used as the approach in these direct interviews. Moreover, most of the time, the questions have not been structured, or predetermined, but asked in an open-ended manner. Borrowing Berger’s (1998) words, the interviews have been “depth interviews” that have aimed to discuss not only “What have people done?” but also “Why have people done it?” (pp. 55-62).

Samples for Observations and Interviews

Since the field research activities have been conducted in a “natural” and “unstructured” setting, observation and direct interview samples have been selected according to situations and events that have occurred during the field research. These situations include, for example, shop owners occupying public spaces by putting their goods in the middle of the road in order to conduct business; people gambling as they play card games along one of the streets; and Hawker Control Team officers standing on street corners. The selection of samples also takes into consideration the demographic factors of the users (for example, age and gender) and their reasons for appearing and remaining at the site. These reasons were determined according to four categories: (a) working and living at the site selected; (b) only living at the site (in the houses/flats located along the street); (c) only working at the site; and (d) making casual “use” of the site (for example, passing by, meeting friends, gathering, shopping, wandering, etc.). As stated above, the observations and interviews have aimed to explore the interactions (coordinations, convergences, conflicts, etc.) of individuals with one another and also with the environment.

Multiple Sources of Evidence

The principle of “using multiple sources of evidence” has been adopted to deal with the problems of establishing the construct validity and reliability of the case studies (Yin, 1994, p. 90). Triangular techniques have also been adopted. Among the six principal types of triangulation in research defined by Denzin in the 1970s, “time,” “space,” and “methodological” triangulations have been selected for use. Regarding time triangulation, cross-sectional studies have been used to collect data concerned with time-related processes from different groups at one point in time; and longitudinal studies have been used to collect data from the same group at different points in time. Therefore, the observation days in the studies include weekends and days on which there were special functions or festivals (both traditional Chinese and Western). Some observations have also been conducted during different periods of time, such as busy hours, early morning hours, at noontime, and so on. Moreover, some observations have not been planned in advance. For instance, in the project on Fu Shin Street, after contacting the Tsat Yeuk Rural Committee (one of the oldest rural committees in Hong Kong) at Tai Po Market, the researchers were invited to attend Lunar New Year gatherings at the Tai Po Committee Centre. That particular visit yielded information that has been useful in understanding the background of the Fu Shin Street site.

The use of space triangulation is an attempt to overcome the parochialism of studies conducted entirely at one small place, for example, a park, a lane, or a district, within the same subculture. Thus, each selected site (street) has been considered as a comparative case for other sites (streets), providing information regarding their similarities and differences.

Methodological triangulation, as applied in these studies, can be defined as using two methods: (a) the same method on different occasions, such as direct observation of a particular event on different occasions; and (b) different methods used on the same object of study, such as non-participant observations, direct interviews with hawkers on a street, and interviews arranged formally with officers related to the particular street.

Findings and Records of the Studies

As already stated, the data of the studies have come mainly from observations and direct interviews. When conducting these activities, notes, photos and video-recordings have been taken. Among all the data, the captured images are particularly important for the analysis, as they can be shown or referred to relevant persons (such as the government officers and representatives of the local communities) for further explanation and comment.

For example, whole day events/happenings on the streets have been captured by video camera. The images (samples), which can be seen in the Appendix, are from video records captured on Fu Shin Street during a whole day of field observations (including direct interviews). These kinds of observations and data recording have been conducted on a regular basis as part of the studies. The captured images and original field notes have assisted the researchers in discussions with relevant persons and in carrying out the data analysis. The field notes presented on the right hand side of the images were revised after discussions with representatives/officers of different parties and with some residents.

Strategies and Tactics

The findings of the studies (including literature and policy reviews, empirical studies, etc.) show that, on the one hand, the government (including policymakers, planners, designers, executives and implementers) continuously sets up strategies and seeks greater authority to control and organize city spaces. Most of the time, their way of thinking is similar to modernist ideas in planning (such as Le Corbusier’s (1930/1991, p. 68) idea of “putting in order”). The government views planners and designers as experts, sometimes as the only experts who can and should be allowed to change existing misused city elements, including any city space, into efficient tools and, in turn, to provide true order in the city.. The government also views contemporary plans (or designs, the modern term now commonly used by the government) as the only way to provide a suitable place for humans, who are defined as average people with standard needs, and provide them with conditions that will ensure general happiness and harmony. This way of thinking rejects the possibility that city users-individuals-are able themselves to find and manage a way to live in the environment, including public spaces, that best suits their everyday lives.

|

Figure 4. Chun Yeung Street in the 1970s. Three rows of stalls were built on two sides of the street as part of the “Stabilization” policy for hawkers. At that time, the Hong Kong Government had relatively little control over such kinds of public spaces; as a result, some unlicensed hawkers could still earn a living on the street. (Source: Hong Kong Urban Council Annual Report 92-93) |

|

Figure 5. The street under development in the early 1990s. Starting in the mid 1980s, the government began to make public spaces increasingly more regulated and “programmed” by establishing more ordinances and regulations. (Source: Hong Kong Urban Council Annual Report 92-93) |

On the other hand, the findings illustrate that city users continuously seek “opportunities” under the strategies promulgated by the government. Most of the time, city users do not act directly against or challenge the government’s strategies; rather, they make use of tactics in their use of public spaces, these tactics being a calculus that does not count on a “propre.” As de Certeau (1984) mentions:

…the place of a tactic belongs to the other ...and tactic insinuates itself into the other’s place, fragmentarily, without taking it over in its entirety, without being able to keep it at a distance. (p. xix)

For instance, the unlicensed hawkers on these market streets do not set up business in a place circumscribed as propre in response to the Hawker Control Teams (also called General Affairs Teams). The hawkers do not sell their goods in permitted areas, apply for hawker licenses, or fight for legislation that will make unlicensed hawking a kind of legal activity. The hawkers, along with other users of other public spaces, usually do not expect to “share authority” or to “use a legitimate basis to substitute for the existing legitimate basis” (Habermas, 1973/1995, p. 33). Rather, they insinuate themselves into the areas of control and authority of the Hawker Control Teams in order to “survive” (Siu, 2003). These tactical practitioners do not have a space, or, it could be said, their space “is the space of the other” (de Certeau, 1984, p. 37). Their tactics depend totally on time. Hence, whatever advantage the hawkers might win they do not keep. They constantly need to manipulate events in order to turn them into opportunities, and continually resort to their own means. As Lefebvre (1984) and Wander (1984) say, this kind of tactical act is “an art of everyday life” and “a radical reorganization of modern life.”

Figure 6a-d. Stall owners use their own ways (i.e., creative acts; tactics) to extend their “temporary” shelters, canvasses and racks in order to expand their business areas. These are seldom “permanent” constructions. When government officers issue warnings to the stall owners, they will retrieve their temporary constructions within several minutes in order to avoid a direct confrontation with the officers. Such retractable constructions are also a comfort to the government in that they can be removed quickly for emergency reasons.

Public Sphere / The Third Realm

The findings of the studies also show that it is not appropriate to presuppose that the government and users of public space are in a binary dichotomous opposition. This kind of presupposition of binary opposition is value-laden and will limit the scope for understanding the relationships among the government, users and other related individuals, bodies, and organizations. As the theoretical arguments of Habermas (1973/1995), related to “Public Sphere,” and Huang (1990), related to “The Third Realm,” show, the public space-use system of Hong Kong can be better understood as a combination of: formal and official urban policy and implementation, with its codified laws and ordinances and government departments; informal ways of operating, including well-established customary, traditional, conventional, local, and individual practices; and an intermediate realm in between. In this intermediate realm, the interactions between the government and city users (or, between plans/designs and practices; or, between strategies and tactics) are not a matter of direct confrontation. They do not constitute a brutal wrestling match. This is because, if interaction is simply a face-to-face struggle and negotiation is simply an enactment of “force,” then victory must obviously belong to the one with the greater force: the strong. However, the interesting point here is that the strong, those holding power and authority, may not win all the time. In fact, the weak always have ways of not losing. The tricky thing here is that the weak do not aim to fight a direct battle-a “positional war.” Rather, they are involved in a “guerrilla war.” For example, to avoid formal prosecution, unlicensed hawkers or shop owners who extend their areas or structures illegally on the market streets always take some action to avoid direct confrontation with the Hawker Control Teams or a direct challenge to the authorities. In other words, the weak-the tactical practitioners, escapees, ordinary consumers, creative interpreters, receptors-usually do not directly react to the force, power, authority, or orders of the strong. The weak understand that if their interactions with the strong are only based on the calculus of force, they will lose. Thus, like guerrillas, the weak insinuate themselves into the strong’s space in order to seek opportunities. Also, the weak do not have or keep a space of their own. This way of operating makes it difficult for the strong to display their force against the weak.

|

Figure 7. Unlicensed hawkers (the weak) do not aim to fight a direct battle-a “positional war”-with the authorities. Rather, they are involved in a “guerrilla war.” Officers of the Hawker Control Team often carry out inspections along the street in an attempt to control illegal hawking, but direct confrontations between the officers and the hawkers are rare. Instead, the hawkers respond by conducting their business only during the “non-office” hours of the Hawker Control Team. |

Since the strong (that is, the government-the producers) have authority and power, they do not want to see “uncertainty and diversity,” that is, anything that they cannot determine and master well in a positional war. However, city users are not homogeneous. For instance, even a beggar lying on the ground in the middle of a footbridge or a housewife visiting a market to buy vegetables for her dinner have their own specific traditions, histories, backgrounds, beliefs, needs, desires, expectations, and even dreams. These diversities result in users viewing and conducting their everyday lives in city spaces in different ways. When faced with these unaccountable and continuously changing city “variables,” the government and planners respond by expecting to fix them. In other words, they intend “to transform the uncertainties into readable spaces” for a positional war (de Certeau, 1984, p.36; and also see de Certeau and Giard, 1998), not a guerrilla war, so that the government and planners-the strong-can be sure to win.

This is also the reason why Lynch’s (1965/1990) openness of space (with a high degree of flexibility and freedom) as well as designs that are full-of-flexibility are not commonly seen in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong government considers openness to be equivalent to “uncertainty,” something that the government does not want to see. Therefore, it is nearly a dream to expect that the Hong Kong government would allow the city space of Hong Kong to enjoy a high degree of diversity and flexibility or would allow the possibility of “constant alteration,” as Sennett (1970) has called for.

The Only Way?

Clearly, as explained above, the government and its well-informed planners and designers view and declare diversities, variables, and uncertainties as chaos, as “a kind of disease and the worst enemy of social harmony” (Fishman, 1982, p. 266). Distinct from Sennett’s (1990) idea, which suggests that a city should be a place for a “beginning” (in other words, full of future unknowns), the government and city planners and designers expect to master city spaces through “sight,” by insisting upon a specific “vision,” instead of accepting the need to lead a donkey’s way of life, that is, one without a clear direction or goal (Ahearne, 1995).

De Certeau (1984) describes this kind of propre “vision” or “sight” as “a triumph of place over time” (p. 36). Based on “vision,” the government and planners propose and insist on “planning” to put the city in good order, and to save men (also women) from misfortune. This kind of professional-centered thinking rejects the possibility that city users are able to discover and manage for themselves a better way to live.

Furthermore, by assuming too readily that “statistics” are perfect, planners and designers expect to be able to use precise calculations that will allow them to fold all the variables into a mode, mean, and medium that they can easily determine and control. In short, these professionals view vision together with plans/designs as the only strategy and means that can provide a suitable place for humans to live in-humans, in their definition, as average people with standard dimensions and needs.

However, this kind of strategy, which relies heavily on the calculation (manipulation) of power relationships and the elimination of variables, diversity, and uncertainty, is not free of resistance, nor is it sure to win all the time. More and more social and urban theorists and design critics see the failure of what the “plan” and “design” initially guarantees, its process, and also, in particular, the way of thinking behind it. As de Certeau and Giard (1998) comment, in their article Ghosts in the City, “[the] urban planning destroyed even more than war had” (p.133) They go so far as to lament that urban planning has today raised up “the ruins of an unknown, strange city” (p. 133). Fishman also comments, in Urban Utopias in the Twentieth Century (1982):

Their [planners’ and designers’] claim to be serving the interests of all-the basis of his authority-is now seen as either a foolish delusion or, worse, a hypocritical attempt to impose his own limited values on everyone else. In the recent literature on urban problems, planners have been pictured as arrogant, undemocratic manipulators bent on clamping a sterile uniformity over the diversity of modern life. (p. 267)

Complaining about this kind of modernist thinking, Fishman further asks:

Each [planner and designer ] only fills his ideal city with his buildings, his sense of proportion and color; and, most profoundly, his social values. Would there ever be room for anyone else? ...In attempting to create a new urban order, must [he] repress precisely that complexity, diversity, and individuality which are the city’s highest achievements? (p. 18)

In The Uses of Disorder (1970), Sennett also questions the roles and functions of planners, stating that their rejection of human diversity is simply due to fear, and so consequently they act unconsciously to simplify the world and mould it in their own image. He scoffs at the view of “modern planners” and states that the rejection of diversity is “a form of emotional illness” (p. 24), and an excuse for their refusal to face reality (p. 35). He further states that the “desire of purification” in city planning and design will result in limiting the chances for city users to explore alternatives, in causing more rules to be formed, or establishing more so-called “appropriate standards of behaviours.” (p. 18).

In his article On Architects, Bees, and Possible Urban Worlds (1996), Harvey echoes Sennett by pointing out the current domination of modernist plans and designs, and then suggests that cities in the twenty-first century place more emphasis on diversity and difference, heterogeneity of values, lifestyle oppositions, and chaotic migrations (p. 226). Lynch and Carr (1979/1990) also complain that less and less space for individual self-fulfilment is available in cities. They point out that current planners and designers deeply believe that “control” is equivalent to “good management,” and that allowing the free use of public spaces may offend or endanger users, or even threaten the seat of power (see pp. 413-417).

As the observations collected in the market street studies show, another reason that the “strategies” of the government and planners are not certain to win is that city users are still not homogeneous or average. In fact, they have never been homogenized or normalized, nor have their activities or lifestyles been truncated, no matter how hard the strong have tried to effect control by imposing more order and regulations in the city. This inability results in the existence of different preferences and also different expectations of city users with regard to their living places. This is similar to what Fischer has expressed in To Dwell Among Friends (1982): “Different kinds of people, with different kinds of social preferences, tend to prefer different kinds of places” (p. 8). However, how can users find places that match their preferences?

|

Figure 8. With the redevelopment of North Point, more and more of the original social spaces along the market streets have been eliminated over the past ten years. The government has planned and constructed two small parks for the residents, within just 10 minutes’ walking distance and with good-quality open-space facilities. However, the old residents (including those who have moved to other districts) still prefer to go to the street every morning, where they sit on the stairs of a bridge located at one end of the street and “wait” for their old friends. It remains a place where they can enjoy simple but intimate neighbourhood conversations. |

Just as shop owners and hawkers on the market streets maintain flexible business boundaries in order to gain more space for their business activities, some old residents also assume a flexible approach to using space. They bring their own stools and chairs or ones collected from the street to the public area to create their own sitting space, where they can chat with their neighbours. Likewise, some beggars on the streets use their own bodies to occupy a small space, thus gaining a small area in which to earn their living. As we can see, city users generally prefer not to daydream-that is, not to entertain planning visions- but to use their own everyday tactics to re-construct their own everyday (open) spaces in order to fulfil their own needs and expectations. They take this approach instead of searching around the city for “a space full of openness without social and economic constraints” in which to live (Lynch, 1965/1990). They also do not put a high expectation on having city space as “a maniacal scrapbook [in which the elements] have no relations to each other, no determining, rational or economic scheme” in which they can fill in their favourite colours (Raban, 1974), or “an ideal survival community which is disordered, unstable and without any control” in which they can only experience a sense of dislocation in their lives (Sennett, 1970). The problem is that, in reality, the utopias envisioned by planners do not really exist in current urban life in Hong Kong, where most current city areas are well-defined from the very beginning (i.e., according to intentions and objectives), carefully programmed in their process (i.e., through design and implementation), and predetermined at the end (i.e., in their final forms). In fact, this kind of tactical re-construction of space by city users is not fixed in any kind of environment, since a tactic depends on time, not on a place or on a propre.

With reference to the empirical findings of this research, we come to an understanding that city users do not follow or rely on a constant, imposed style of living and mode of operating in their living spaces. They have their own ways to survive, no matter what degree of openness is allowed or constraint is imposed in these spaces- whether it be the strict plan, design and order that Le Corbusier proposes; the low commitment, low social investment and high intensity of human activity that Lynch expects; or a flexibility in dealing with high density and conflict that Sennett calls for. In order to make a place more inhabitable, city users will take it upon themselves to re-define the meanings and functions of spaces, re-territorialize boundaries, re-build the planned environment, re-establish rules, re-order temporal order, and, in general, to perform whatever additional “re”s they find necessary. Furthermore, these “re”s are not based merely on confrontation, as Sennett has emphasized. They are also based on long-term community interactions, particularly in a place like the market streets of Hong Kong, which have a long history, a strong sense of community, and intimate neighbourhood relationships. The (city) users of these streets have learned how to maintain more control over their lives, and also to be more aware of each other. This fact, and the other points described above are all highly important issues and matters that designers should be aware of, and should understand, respect and feel empathy toward when they propose design solutions.

|

Figure 9. Re-defining meaning and function of a space: The pedestrian walkways on the street are subject to strict prohibitions that do not allow them to be used for any other functions except circulation. Shop and stall owners and residents have established their own small place (calling it “little heaven”) for gathering socially and chatting with neighbours. The chairs and small tables have been collected from the garbage collection point, and thus are all different. |

|

Figure 10. Re-territorializing boundaries: Stall owners use collected chairs and temporary structures/shelters to set up a loose boundary between the road (used for cars) and their business areas. The chairs function not only as a fence, but also as an invitation to neighbours to sit down for a chat. The concrete stand in the right bottom corner is evidence that a temporary shelter could be set up in that area to further extend the business boundary. |

|

Figure 11. Re-building the planned environment: Shop owners with shops on the ground floor of a building have set up a canvas that covers the whole pedestrian area. This kind of construction forms an “inner market” between the buildings and the stalls on the roadside. Such semi-enclosed spaces attract people to stay and chat and take part in other types of human interactions. The stalls on the roadside are also extended by the use of temporary constructions towards the middle of the road. The area of each stall thus becomes nearly three times as big as its original size. |

|

Figure 12. Re-establishing rules: Parking is not allowed on the street during certain time periods. To occupy a parking space for later parking or for delivering goods, shop owners place objects (i.e., any kinds of objects) on the road to “reserve” the space. In some cases, the shop owners do not have cars, but they do not want cars to affect their business. Obviously, these parking-space conventions are not rules that are determined or recognized in any formal way. Nevertheless, all of the neighbours (including residents, shop and stall owners) know these “unspoken” rules, and no outsiders will try to break the rules. |

|

Figure 13. Re-ordering the temporal order: Instead of having social meetings or gatherings at periods set aside for leisure time (such as the times scheduled during the opening hours of the community centre), the residents (including older persons, retired persons and foreign domestic helpers) prefer to meet their friends during the busiest times on the street (8:30 to11:00 a.m. and 4:30 to 6:30 p.m.). This is because these time periods are the most convenient times for them to meet and because they know the regular schedules of their neighbours and friends. Residents can be seen here sitting on the bollards of a tram stop waiting for a social meeting or gathering. |

A Way of Understanding, Respect and Participation

Some may ask, while city users can re-construct their living spaces to fit their own preferences and needs, what are the roles of designers as well as other professionals such as planners and architects? Why, even, is there a need for these kinds of professionals? In fact, starting in the early 1970s, an increasing number of people have indeed recommended a less planned, designed, controlled and governed society, in particular when it comes to daily living spaces and communities. Obviously, such laissez-faire and anarchistic opinions have received some support, but not as much as they have received objections. We cannot deny that this is still a topic requiring more discussion and more flexible consideration and action according to different physical, environmental, cultural, social, religious and political situations.

Nevertheless, one point that is sure is that designers should review their roles and apply their talents in a correct direction. The findings and experience of the studies discussed above offer designers as well as other professionals such as planners and architects insight into the fact that the focus of planning and design should be shifted from producers (professionals, administrators, developers) and products (e.g., an international centre of finance, a popular tourist destination, a world-class city, an “attractive” design object, a signage, a slogan) to users (citizens). In other words, designers should adopt a user-oriented perspective. The knowledge and experience of designers should not become a weapon with which they impose their personal preferences on users and suppress those users’ actual preferences and needs. Instead, designers need to make good use of their knowledge and experience so as to assist users to fulfil their own preferences and needs.

The studies of this research also illustrate that, in particular relating to city and environmental planning and design, a good-quality living environment should not be a place planned and designed solely by government officers, planners, designers or developers who are foreigners to that place. As stated by Coenen, Huitema and O’Toole (1998), the city users-the inhabitants-of a specific place know their own needs and are more familiar with their living environment than foreign policymakers and professionals. As can be seen in the example of the daily routines of Fu Shin Street illustrated above, the street users-shop and stall owners, hawkers, residents, passers-by, etc.-know what they like and need, and also take action accordingly. This high degree of “person-environment (P-E) fit” would never have been obtained without the street users participating in changing/modifying their environment. Therefore, to obtain a street environment with a good P-E fit, first of all, designers need to learn how to see and listen to the way that street users live. Second, designers need to respect the everyday lifestyles of individual street users (Sanoff, 1992, 2000; Schuler, 1993). Third, they need to think about and take action regarding how to facilitate an environment to fit these user preferences and needs (Hsia, 1993; Siu, 2005).

More specifically, designers need to take a more active role instead of just complaining and blaming the helpless; designers need to change their role from that of commander and decision-maker to coordinator and facilitator (Hsia, 1993; Liu, 1995; Sanoff, 2000). While users must necessarily be considered the centre and focus of the whole design process, what designers should attempt to do is to review, investigate and then develop a keen understanding of the diverse preferences and needs of users. In addition, besides understanding, designers also need to acknowledge and respect the preferences and needs of users, since only through such acknowledgement and respect will designers be qualified and motivated to propose and produce user-fit solutions (Siu, 2003).

To go a step further, merely understanding and respecting users’ preferences and needs is still a relatively passive approach; there remains the question as to why designers do not take a more active role in providing opportunities for city users to participate in the design of their living environment. In other words, the designers’ job is no longer simply to carry out data investigation inside their offices and to produce their own finished and unalterable solutions based on their own imagination. Instead, designers must generate more design alternatives and options that must come about from continuous communications and interactions with city users (Siu, 2003, 2004; Siu & Kwok, 2004). The energy and imagination of designers should be directed toward raising the level of awareness of users by taking part in discussions with them, and design solutions should come out of exchanges between the two sides: Designers should state opinions, provide technical information and support, and discuss the consequences of various alternatives and options, and city users should also state their opinions and contribute their expertise (Hsia, 1993; Powell, 2001; Sanoff, 1992, 2000; Siu & Kwok, 2005).

It is easy to recognize that user-oriented design based on field investigation (for example, behaviour observations) and user participation in the design process will always require a relatively longer period of time and additional resources. However, such limitations and difficulties should not be an excuse-the kind that policymakers and designers nowadays commonly like to make-to reject this kind of design approach. On the contrary, it is far more worthwhile for governments and professionals to consider this approach seriously and to inject the necessary additional resources, since this approach is the best way to “obtain” and “maintain” a living environment that is inhabitable and that is characterized by variety and vitality-a place that is full of liveliness and that is fit for its users (Bradshaw, 1996).

To conclude, as society, cities, and users change continuously, dynamically and interdependently, the provision of city spaces and constructions, especially public spaces and facilities, should not be fixed and inflexible. By the same token, user-oriented design cannot also remain unchanged. As Abbott comments (1996), it is difficult to obtain a high-quality living environment through short-term and piecemeal-type contributions of designers and city users. Environmental improvement and community development require long-term investment and operation. Thus, designers should work continuously with city users in conducting investigations, and in planning, designing, implementing and, most importantly, maintaining the quality of the environment. As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, empirical studies on users’ reception of public spaces are rare. Designers participating in this kind of study are even rarer. Simply speaking, designers need to undertake more trials and obtain more feedback in the way of empirical studies at different scales and levels. Designers also need to undertake further investigations to enrich their understanding of how different city users interact with the environment in their everyday lives, and what kinds of spaces they truly need. Carr, Francis, Rivlin and Stone (1992) have stated clearly that when designs are not grounded in understanding, “they may fall back on the relative certainties of geometry, in preference to the apparent vagaries of use and meaning” (p. 18). We also need to explore more new and alternative methods and tools of investigation in order to meet physical, environmental, cultural, social, religious and political changes. As early as 1971, Armillas pointed out that “we lack a methodology for incorporating the user into the decision-making process” (p. 38). Similarly, Francis and Hester (1990), also state that, these days, the problem is not that designers are lacking in creative ideas but rather that they are frequently hampered by not having the time to search out appropriate user-oriented research. Today, and not only in Hong Kong, where the above case studies were conducted, we still lack serious investigation into and implementation of a user-oriented approach in the design of the living environment. Therefore, we agree that if user-oriented design is to be a meaningful and productive city design approach, then ways of understanding and involving city users must be developed, particularly to suit the different contexts of different particular cities. Undoubtedly, it is only through this kind of long-term professional contribution, user participation, action investigation, and also government recognition and resource support that a quality living environment can be maintained to suit the ever-changing needs of cities and their citizens.

Acknowledgments

All field observation photos were captured by the author and his research assistants. The author would like to acknowledge the resources extended by the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to support this study, the support of the Fulbright Scholarship and Asian Scholarship Foundation in the preparation of this paper, and the information provided by the Hong Kong SAR Government Departments and Related Organizations, including the Urban Renewal Authority, Highways Department, District Boards and Councils, Home Affairs Bureau, Food and Environmental Hygiene Department, Census and Statistics Department and Leisure and Cultural Services Department. The author would also like to acknowledge the two photos adopted from the Urban Council Annual Report 92-93, Hong Kong SAR Government; and the Hong Kong Guide Book 2000 for the three extracted street maps. The author would in addition like to express thanks for the comments of Professor Tunney Lee and Professor Hsia Chu-joe. The author would in addition like to express thanks for the comments of Professor Julian Beinart, Professor Tunney Lee and Professor Hsia Chu-joe.

References

- Abbott, J. (1996). Sharing the city: Community participation in urban management. London: Earthscan Publications.

- Ahearne, J. (1995). Michel de Certeau: Interpretation and its order. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Andranovich, G. D., & Riposa, G. (1993). Doing urban research. London: SAGE.

- Armillas, I. (1971). Gaming--simulation: An approach to user participation in design. In Design participation: Proceedings of the Design Research Society’s Conference. London: Academy Editions.

- Barker, R. (1968). Ecological psychology: Concepts and methods for studying the environment of human behavior. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Berger, A. A. (1998). Media research techniques (2nd edition). London: SAGE.

- Bradshaw, M. (1996). Variety and vitality. In D. Chapman (Ed.), Creating neighbourhoods and places in the built environment (pp. 110-129). London: E & FN Spon.

- Carr. S., Francis, M., Rivlin, L. G., & Stone, A. M. (1992). Public space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Coenen, F. H. J. M., Huitma, D., & O’Toole, L. J. (1998). Participation and the quality of environmental decision making. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

- de Certeau, M., & Giard, L. (1998) Ghosts in the city. In M. de Certeau, L. Giard, & P. Mayol, P. (Eds.), The practice of everyday life: Volume 2: Living & cooking (T. J. Tomasik, Trans.) (pp. 133-144). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Denzin, N. K. (1970). The research act in sociology: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. London: The Butterworth Group.

- Fischer, C. S. (1982). To dwell among friends. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

- Fishman, R. (1982). Urban utopias in the twentieth century: Ebenezer Howard, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Le Corbusier. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Francis, M., & Hester, R. T. (1990). The meaning of gardens: Idea, place, and action. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Habermas, J. (1995). The public sphere (Öffentlicheit) (in Chinese). In J. Habermas et al. (Eds.), Socialism (pp. 29-37). Xianggang: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1973)

- Harvey, D. (1996). On architects, bees, and possible urban worlds. In C. C. Davidson (Ed.), Anywise (pp. 216-227). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Hsia, C. J. (1993). Urban process, urban policy, and participatory urban design. In C. J. Hsia (Ed.), Space, history and society (pp. 247-268). Taipei: Taiwan Social Research Studies-03.

- Hsia, C. J. (1994). Public space (Chinese ed.). Taipei: Artists.

- Huang, P. C. C. (1990). The peasant family and rural development in the Yangzi Delta, 1350-1988. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Le Corbusier. (1991). Precisions on the present state of architecture and city planning. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. (Original work published 1930)

- Lefebvre, H. (1984). Everyday life in the modern world (S. Rabinovitch, Trans.). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Liu, K. C. (1995). Environmental design and community participation. In Settlement Conservation and Community Development, Living in Taiwan: An interview with Professor Hsia C. J. and Liu K. C. (Chinese ed.). Han Sheng Magazine, 74, 77-80.

- Lynch, K. (1990). The openness of open space. In T. Banerjee & M. Southworth. (Eds.), City sense and city design: Writings and projects of Kevin Lynch (pp. 396-412). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. (Original work published 1965)

- Lynch, K., & Carr, S. (1990). Open space: Freedom and control. In T. Banerjee & M. Southworth. (Eds.), City sense and city design: Writings and projects of Kevin Lynch (pp. 413-417). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. (Original work published 1979)

- Merriam, S. B. (1988). Case study research: A qualitative approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Powell, F. W. (2001). The politics of social work. London: SAGE.

- Raban, J. (1974). Soft city. London: Hamilton.

- Rutledge, A. J. (1985). A visual approach to park design. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

- Sanoff, H. (1992). Integrating programming, evaluation and participation in design: A theory Z approach. Hants: Ashgate.

- Sanoff, H. (2000). Community participation methods in design and planning. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Schuler, D. (1993). Participatory design: Principles and practices. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Sennett, R. (1970). The uses of disorder: Personal identity and city life. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

- Sennett, R. (1990). The conscience of the eye: The design and social life of cities. Boston, MA: Faber and Faber.

- Siu, K. W. M. (2003). Users’ creative responses and designers’ roles. Design Issues, 19(2), 64-73. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Siu, K. W. M. (2004). Street furniture design. In T. P. Leung (Ed.), Hong Kong: Better by design (pp. 77-86). Hong Kong: The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

- Siu, K. W. M., & Kwok, J. Y. C. (2004). Collective and democratic creativity: Participatory research and design. The Korean Journal of Thinking and Problem Solving, 14(1), 11-27.

- Siu, K. W. M., & Kwok, Y. C. J. (2005). Respecting and understanding users: Public space furniture design for older persons. Harvard Asia Pacific Review, 8(1), 49-52.

- Wander, P. (1984). Introduction to the transaction edition. In H. Lefebvre, Everyday life in the modern world (pp. vii-xxiii). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Whyte, W. H. (1988). City: Rediscovering the center. New York, NY: Doubleday.

- Yin, R. K. (1993). Applications of case study research. London: SAGE.

- Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (2nd edition). London: SAGE.

Appendix

Video records captured on Fu Shin Street during a whole day of field observations, with descriptions based on observations and direct interviews