Ten Ways to Design for Disgust, Sadness, and Other Enjoyments: A Design Approach to Enrich Product Experiences with Negative Emotions

Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands

This paper demonstrates how designers can enrich user experiences by purposefully involving negative emotions in user-product interaction. This approach is derived from a framework of rich experience, which explains how and under what circumstances negative emotions make a product experience richer and enjoyable. The approach consists of three steps, where the designer decides 1) which negative emotion is most appropriate for the user context; 2) how and when this emotion is best elicited; and 3) which protective frame is most appropriate to use and in what way it is applied to the product concept. Ten experience qualities were developed that offer prefabricated combinations of these steps, which are intended to lower the threshold of using the approach. The steps for these qualities are described, and each is briefly discussed. Lastly, the applicability of the approach in design is demonstrated by showing six examples of how the qualities have been used to generate concrete product concepts. Reflecting on the approach, we conclude that negative emotions are a viable and interesting starting point for creating emotionally rich product experiences.

Keywords – Design Approach, Emotional Design, Negative Emotion, Rich Experience.

Relevance to design practice – This paper describes a design approach that methodically uses negative emotions to add engagement, refreshment or meaning to situations that are generally boring or empty, and to make use of the specific effects of negative emotions on attitude to stimulate people in activities that they would otherwise not engage in.

Citation: Fokkinga, S. F., & Desmet, P. M. A. (2013). Ten ways to design for disgust, sadness, and other enjoyments: A design approach to enrich product experiences with negative emotions. International Journal of Design,7(1), 19-36.

Received March 16, 2012; Accepted November 3, 2012; Published April 30, 2013.

Copyright: © 2013 Fokkinga and Desmet. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

*Corresponding Author: s.f.fokkinga@tudelft.nl

Introduction

Consider the following new product concepts: a digital nutrition assistant that elicits disgust in people who are grocery shopping, a thermometer that makes feverish children feel sad when it takes their temperature, and a digital exercise coach that makes running laps a frightening experience. These concepts may seem strange at first glance. Indeed, by eliciting negative emotions their purpose seems even contrary to that of experience design: to provide people with pleasurable product experiences. However, we believe that these concepts illuminate a promising new direction in experience design.

Several authors have published guidelines for experience-driven design. Although diverse, these existing approaches share the objective to provide guidance in designing products that stimulate positive emotions and experiences. For instance, Jordan (2000) suggested four sources of product pleasure, Norman (2004) discussed three cognitive levels of pleasurable product experiences, Desmet (2008) proposed nine sources of product appeal, and Arrasvuori, Boberg, and Korhonen (2010) surveyed and categorized 22 different ways for products to elicit playfulness. In this paper we outline an approach that is different in purpose and even opposite in its consideration of emotions. It is different in purpose because it aims to create rich experiences rather than pleasure, playfulness or positive appeal, and opposite in its consideration of emotions because it conceives negative emotions at the basis of these rich product experiences. Our aim is to show how product concepts eliciting negative emotions, like the ones proposed above, can be created to systematically enrich user experiences.

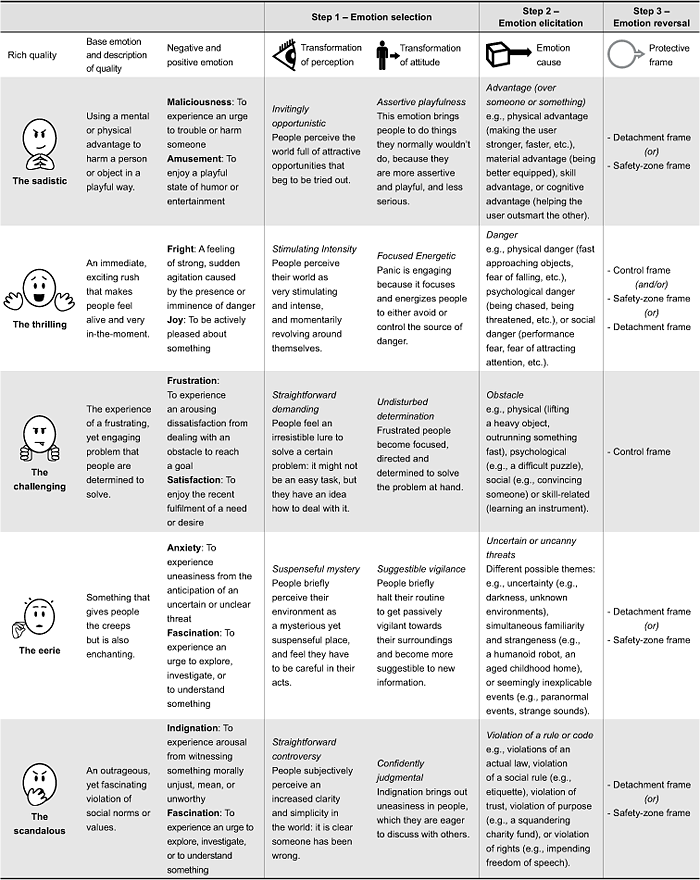

To show why and how negative emotions have a central role in rich experiences, it is necessary to define what is meant by that last term. Firstly, the English word ‘experience’ can refer to a momentary experience of a single event (in German: ‘Erlebung’), such as the experience of pain, but also to an episode of multiple experiences that form a coherent whole (in German: ‘Erlebnis’), such as the experience of traveling by airplane. Rich experiences are examples of such integrated ‘Erlebnissen’, whereas the specific emotions of which they are composed are mostly individual ‘Erlebungen’. Secondly, to accurately define our notion of rich experiences, we will identify the key characteristics that set them apart from non-rich experiences, thus gradually narrowing the scope of definition. This definition-by-exclusion is visually represented in Figure 1, which also shows examples of the different types of experiences. First of all, rich experiences are somehow a-typical and therefore notable and memorable (2.), setting them apart from ordinary or mundane experiences that involve neutral, mildly positive or mildly negative emotions (1.). Secondly, rich experiences are differentiated from other notable experiences by being pleasant or by having some kind of beneficial effect on the experiencing individual (2.2). This criterion excludes experiences that are notable, yet unpleasant and without any value to the person experiencing (2.1). The remaining set of experiences can again be divided into two categories, yielding a set of experiences that only involve strongly positive emotions (2.2.1), and a set of experiences that involve a mix of negative and positive emotions (2.2.2). In brief, rich experiences are notable and memorable experiences that involve a mix of positive and negative emotions and are experienced as valuable, because they are pleasant, beneficial, or both.

Figure 1. Rich experiences defined by comparison to other types of life experiences.

Although both of the final categories (2.2.1 and 2.2.2) are highly interesting for design, there are a few reasons why we focus on rich experiences in this paper, instead of on highly favorable ones. First of all, it is difficult to durably elicit strong positive emotions with everyday products. Such emotions are usually only evoked by personal goal achievements or by highly favorable life events (e.g., Lazarus, 1991, pp. 265-269), in which products normally play a supportive role at best (Desmet, 2002). Products are in some cases able to elicit certain strong positive emotions, but those are either singular and short-lived (e.g., positive surprise, Ludden, 2008) or unattainable to most people, such as the satisfaction evoked by flying first-class. However, apart from issues of feasibility, the use of rich experiences can be justified primarily by their ability to offer unique experiences that purely positive (or negative) experiences cannot provide. A phenomenological study, published in another paper, uncovered two main types of rich experiences with mixed emotions (Fokkinga & Desmet, 2012b). Firstly, some of the most interesting and enjoyable things in life are not simply positive or negative. This is evident in the experience of art and entertainment: gloomy music makes listeners feel melancholic, shock art may disgust or outrage people, and movies even elicit a whole spectrum of negative and positive emotions over the course of their narrative (Tan, 1996, pp. 1-2), but all of them are highly enjoyable and actively sought out. Secondly, negative emotions can have beneficial mental and bodily effects on the experiencing individual, which can lead to a positive overall experience. For example, one participant in the study stated that the rage she had over an unfair evaluation made her feel very energetic, focused, and righteous, which helped her to formulate an articulate reply to challenge the evaluation. Another participant said that the sadness she felt when saying goodbye to her grandparents had a positive effect, because it made her realize their importance in her life (Fokkinga & Desmet, 2012b).The study also found two types of mixed emotional experiences that were not perceived as rich: experiences in which the causes of the emotions were mutually unrelated (e.g., someone is happy with the look of his car, but dissatisfied with its energy consumption), and experiences in which the positive emotion preceded and caused the negative emotion (e.g., someone hoped her friend would fall so she would win the wall-climbing competition, but felt ashamed about this afterwards). Thus, even though rich experiences involve mixed emotions, not all mixed emotion-experiences are necessarily rich. Another important observation was that it is simplest and most elegant to conceptualize the negative emotion as primary and the positive emotion as secondary in the formation of rich experiences. For instance, it is much easier to explain that shock art is fascinating because it is outrageous, or that roller coasters are fun because they are scary, than the other way around.

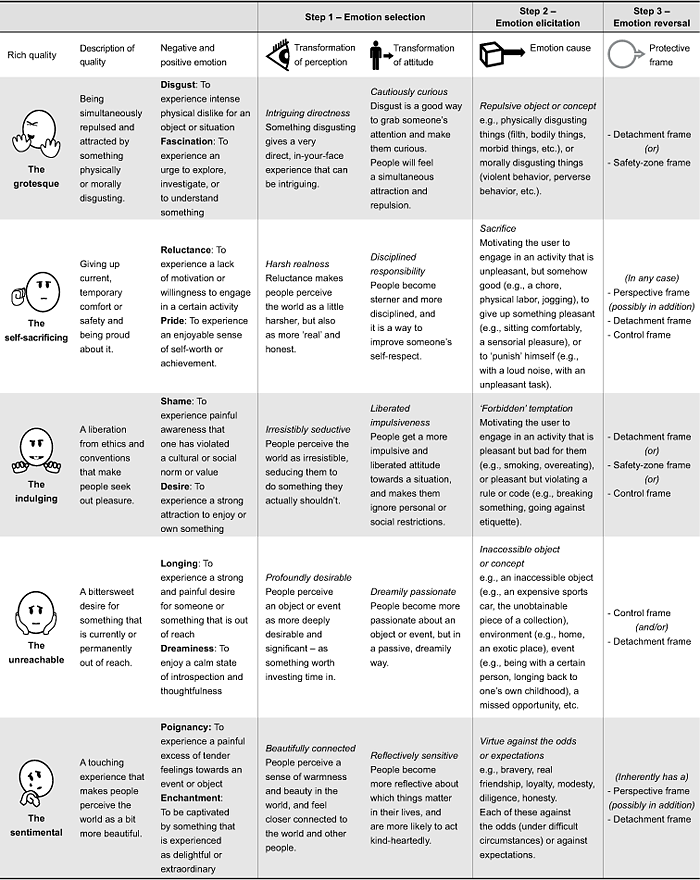

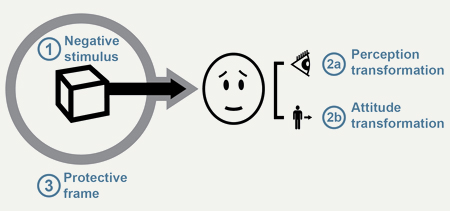

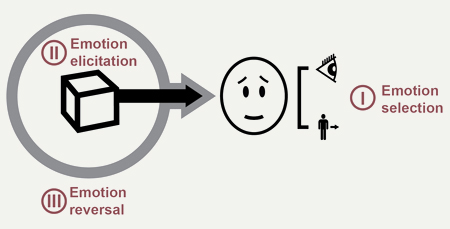

This last observation was at the basis of an explanatory framework that suggests how rich experiences can be formed in human-product interactions, which we proposed in another paper (Fokkinga & Desmet, 2012a). In this framework, rich experiences consist of three ingredients: a negative stimulus, subjective transformation, and a protective frame (see Figure 2). The negative stimulus is the element of a product or product interaction that evokes the negative emotion. For instance, a certain product feature may seem threatening to the user, and elicit fear. Secondly, negative emotions enrich experiences because they bring about a perception transformation and attitude transformation in an individual, which constitute two sides of the same effect. A perception transformation changes what a person attends to in the world around him, how he experiences time and space, which meaning he derives from events, and how sensitive he is to certain information, among other things. For instance, a frightened person will momentarily perceive the world as more lively, urgent, and revolving around himself. Analogously, an attitude transformation changes a person’s view on his own position in the world and his tendency to act upon it. For instance, an angry person tends to feel more impulsive, direct, and assertive towards his surroundings. Every negative emotion produces a unique transformation of perception and attitude, so each of them enriches the user experience in a distinct way. The third ingredient of the framework is the protective frame, which takes away the unpleasant aspects of the negative emotions to allow the user to enjoy its beneficial aspects. Four different protective frames were identified for use in design: the safety-zone frame, the detachment frame, the control frame and the perspective frame, all of which can be applied separately or jointly. The framework was inspired by Sartre’s conception of emotions as transformations of the world (Sartre, 1939/1962), but underpinned by insights of contemporary emotion psychology, particularly areas of appraisal theory that focus on bodily and mental effects of emotions (e.g., Frijda, 1986; Fredrickson, 2004) and the distinction in these effects across different emotions (e.g., Lerner & Keltner, 2000; Rucker & Petty, 2004). Lastly, the concept of the protective frame is derived from the work of Apter (2007).

Figure 2. The rich experience explanatory framework (adapted from Fokkinga & Desmet, 2012a).

This paper demonstrates how the three ingredients of the framework can be applied consecutively in a three-step design approach. This approach and the design steps are discussed in the first section. Next, the paper introduces ten rich experience qualities that follow specific ‘prefabricated’ combinations of these steps, each evoking a different combination of a negative and a positive emotion, and thus each enriching a product experience in a different way. The subsequent section offers a detailed description of the ten rich qualities, with examples of their occurrence in real life and product use, as well as a discussion of relevant literature. Several rich qualities are then exemplified with concept design cases, including the examples of the first paragraph of the Introduction. Lastly, we reflect on the use of this approach and discuss some implications of this new way of constructing emotional product experiences.

Adapting the Framework to a Product Experience Design Approach

With the proposed framework in Figure 2, the formation of emotionally rich experiences can be conceptualized. However, apart from analyzing and explaining rich product experiences, this framework can also guide designers in creating them. In a design process, the three ingredients can be applied consecutively in three steps (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The rich experience design approach.

In the first step, the designer chooses which negative emotion to evoke in the product experience, based on an understanding of which transformation of perception or attitude might be desirable in the user’s situation. Thus, the second ingredient of the framework is the first step in the approach, because the specific subjective transformation (produced by a specific negative emotion) determines what kind of rich experience the user will have. For instance, if the user context is a waiting room in which people are generally bored, the designer might opt to design something that makes the waiting experience more exciting and lively (transformation of perception), in which case fright would be an appropriate emotion. Or, if the brief is to design something that makes students calmer and feel more connected to their history lesson, the design could elicit sadness (transformation of attitude). The transformations are essentially two sides of the same effect, as they are both the result of the bodily and mental changes that occur with an emotion. However, they have been treated separately to make a distinction between two perspectives that designers can adopt when considering the effect they want to achieve in the user context. If a designer is mostly concerned with the user’s subjective experience of a situation, transformation of perception might be the most relevant to consider. In contrast, if a designer is mainly interested in changing a user’s behavior, a focus on attitude transformation might be more worthwhile. Unfortunately, when considering transformations as a guideline of emotion selection, there is one obvious challenge. Although there is much knowledge about specific bodily and mental effects of different negative emotions [for instance, Rucker and Petty (2004) found that sadness makes people prefer passive activities, whereas anger makes them prefer active ones], there are, to our knowledge, no clear and empirically rooted overviews of the integral transformations that different negative emotions produce. This problem will be addressed in the next section, in which ten pre-researched negative emotions are proposed for use in the approach.

In the second step, the designer needs to find an appropriate way to evoke the chosen emotion in the user. Several researchers have made overviews of the causes for specific emotions (e.g., Ellsworth & Scherer, 2003, p. 583; Frijda, 1986, p. 218; Lazarus, 1991, p. 122). For instance, fear is evoked when something threatens a person, whereas sadness is evoked by a loss (Lazarus, 1991, p. 122). Emotion researchers use such causes to explain why people have certain emotions in a given situation, but designers can use them the other way around–to create the circumstances that elicit the chosen emotion in the user. However, there is often a high level of abstraction in the description of these causes because they cover large themes. For example, a variety of situations evoke fear because they all represent different kinds of threats: e.g., looking down from a great height (threat of falling down), forgetting to lock one’s car (threat of losing property), or suddenly having to speak for a large audience (threat of social embarrassment). Thus, the designer still has to decide on a concrete way to put the abstract cause into the product experience. The role of the product in this can be both direct and indirect. In the direct role, the product evokes the emotion through sensory impression or through usage. In the indirect role, the product can motivate the user to undertake certain behavior, or reveal a certain quality in the world, which in turn evokes the emotion. In addition to introducing a new negative emotion in a product interaction, the designer can also use a negative emotion that is already present in the targeted user context. For instance, when designing a product for children in a hospital, the designer can use the anxiety or sadness that is intrinsic to such an environment, and redirect these emotions to a less unpleasant source.

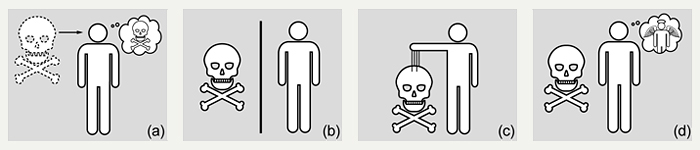

In the last step, the designer creates a protective frame that reverses the negative emotion so that it can be enjoyable for the user. The protective frame is a mental construct that detracts the unpleasant aspects from the experience of a negative object or event (Apter, 2007), while leaving the transforming effects intact. For instance, when people interact with a caged lion, they will experience the same transformation of perception (stimulation and focus) and attitude (pumped up and energized), but without the subjective evaluation that their lives are in danger. Although the protective frame is a mental construct, it can be (and often is) induced by designable circumstances, as the case of the caged lion shows. To understand the different ways in which negative emotions can be enjoyable in product experience, four protective frames were proposed (Fokkinga & Desmet, 2012a). Each of these four frames can be employed by designers to make the negative emotion enjoyable.

Figure 4. Four types of protective frame: (a) the detachment frame, (b) the safety-zone frame, (c) the control frame, (d) the perspective frame.

The detachment frame (Figure 4a) is constructed by altering the stimulus of the negative emotion in such a way that users are only confronted with a representation of it. For instance, instead of interacting with a real-life lion, users can interact with a graphic, movie, story, audio recording or even a symbolic representation of a lion. The occurence of this frame is common in the experience of negative emotions in art and entertainment. There are several sub-strategies that lead to a detachment frame, some of which are stronger than others. For instance, the negative stimulus can be represented by abstraction–e.g., reading about the number of victims of a disaster rather than seeing photographs of them; by simplification–e.g., a line drawing of a wound rather than a photograph; by stylization–e.g., a beautiful picture of a collapsed building; or by overemphasis–e.g., the exaggeration of violence ad absurdum in slasher movies.

The safety-zone frame (Figure 4b) is constructed by physically distancing users from the negative stimulus, so they are literally or figuratively in the ‘safe zone’. Unlike the detachment frame, the safety-zone frame still lets the user interact with the actual negative stimulus. This frame can be constructed by creating a distance between the user and the stimulus (e.g., designating seats that are outside of the splash zone at a dolphin show), or by creating a barrier between the user and the negative stimulus (e.g., a fence that prevents people from falling from a rooftop). Not all barriers are necessarily solid and static–a child can use a twig as a safety-zone frame to probe a dead bird without having to touch it, while still feeling fascinatingly disgusted.

The control frame (Figure 4c) is constructed by increasing the amount of control that a user has over the interaction with the negative stimulus, taking into account any skills and abilities that the user already possesses. This control can relate to physical skills (e.g., the user is fast, strong or agile enough to avoid or deal with the negative stimulus) and mental abilities e.g., the user is smart, knowledgeable, perceptive or creative enough to avoid or deal with the negative stimulus). Design can support or improve skills of both categories. For instance, a product (feature) could temporarily increase a person’s load capacity (e.g., anchoring rope in rock climbing), it could increase a user’s perceptiveness by alerting him to impending danger (e.g., proximity sensors in car bumpers) or it could increase a user’s creative problem solving by providing hints (e.g., the suggestion function in printers with a paper jam). Sometimes a control frame is as simple as giving users the ability to ‘opt out’ of the experience of a negative stimulus. Even though they may never use the option, the knowledge that it is possible at any time can provide a sufficiently strong frame for the user to enjoy the experience.

The perspective frame (Figure 4d) can be constructed by providing a perspective on the wider implications of the negative stimulus or the user’s reaction towards it. For instance, a person may feel reluctance towards getting up early in the morning, but if she is able to see the beneficial implications of her early awakening (e.g., being able to get more work done, being ahead of other commuters in traffic), she can feel proud about her own behavior. A good way to approach the creation of a perspective frame through design is by connecting the negative situation to specific virtues. Virtues, such as those promoted by Aristotle (2009), are character qualities that are considered morally good and socially beneficial. For instance, getting up early (eliciting reluctance) can be connected to the virtue of diligence, whereas getting close to a lion (eliciting fear) can be connected to courage. Other examples of virtues are loyalty (e.g., ‘taking one for the team’), self-actualization (e.g., observing one’s own progress in mastering a difficult skill), altruism (e.g., participating in a charity run), modesty (e.g., declining an expensive present), and sincerity (e.g., telling the truth against one’s own interest). The connection between the situation and one of these virtues will depend heavily on the specific context. In the case of the early riser, for example, the virtue of diligence could be introduced through an alarm clock that shows how many other people have already gotten up at that time, so the user can immediately see she is one of the first and feel good about herself.

By following these three steps, designers can come up with conceptual ideas for a product or product feature that afford rich experiences. However, it should not be considered a ‘cookbook’ for the creation of rich product concepts. The steps are rather guidelines that can help to structure the designer’s thought process and facilitate discussion among different team members working on a project.

Ten Rich Experience Qualities

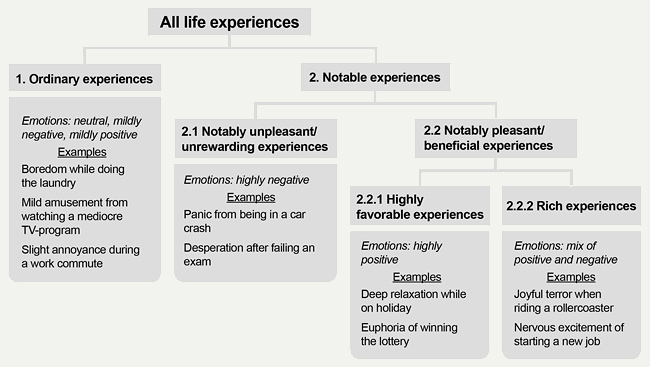

In this approach, any negative emotion, combined with a protective frame, can be the basis for a rich experience, provided that it is elicited in an appropriate user context. This means that the number of possible rich product experiences is in principle at least as extensive as the number of negative emotions. However, to get a more tangible impression of the possibilities of the approach, we elaborated ten specific rich experience qualities that we believe are worthwhile in user-product contexts. ‘Experience qualities’ (or just ‘qualities’) in general are a concept used by designers to specify the type of experience the user should have with a product, without yet establishing functional properties or even the type of product. It is akin to what Hassenzahl (2010, pp. 17-19) calls an ‘experience pattern’: the essence of an experience that can be manifested differently in different situations. The rich experience qualities specifically were developed by elaborating the three steps of the approach for ten different negative emotions. Table 1 shows the overview of the ten rich qualities with a short description and the three elaborated steps. Designers can use this overview as a guideline for experimenting with the different emotions and rich experiences.

Table 1. Three-step application of ten rich experience qualities. (Click to enlarge this table.)

The following sub-sections elaborate the nature and background of the ten qualities in more detail, by showing examples of their occurrence in real life and references to literature from psychology and the humanities. Most of the qualities also feature a product example. Since rich qualities are (still) very scarcely used in mainstream products, most examples were derived from ‘critical design’ or from products designed for entertainment. For purposes of structure and efficiency, we clustered the qualities into four categories, as some have similarities between them that can be discussed jointly.

Negative Emotions Stimulate and Focus

This category contains qualities that use the stimulating and arousing effects of negative emotions like fear, anger, and frustration. These emotions have in common that they direct the attention of the user at a specific problem, and energize him or her to avoid or deal with a problem.

The Sadistic (Maliciousness + Amusement)

The sadistic is the enjoyment that people draw from taking revenge, putting somebody back in their place, or playing a prank. The governing condition in all these cases is that people have the opportunity to exploit an advantage they have over another person or object. This might sound extreme, but in nuanced forms this experience is relatively harmless and socially accepted. For example, office workers can exploit their colleague’s trust and unsuspecting nature by playing a practical joke (Figure 5a). However, a harmful act can also be socially useful, if it is directed at institutions or ideas that are though to have a lot of power. In that case, the perpetrator is seen as the underdog and the harmful act as an expression of rebellion. For instance, making a joke about religion, mocking a person of authority (Figure 5b) or disproving a powerful scientific theory can all be enjoyable for this reason. This quality also manifests itself in the feeling of sweet revenge, when the act is meant as punishment for someone else’s unacceptable behavior (see Knutson, 2004). De Quervain et al. (2004) demonstrated that taking revenge activates a part of the brain that is associated with mental satisfaction and reward. Pain Station is an art installation in the form of an arcade video game that utilizes the sadistic quality (Figure 5c). Two users play a game of pong, while holding one hand on the so-called pain execution unit (Morawe & Reiff, n.d.). Through different playing styles, the users have the opportunity to inflict different types and intensities of pain in their opponent, thus raising the stakes and the enjoyment in the game.

Figure 5. The sadistic quality: (a), (b), and (c).

The Thrilling (Fright + Joy)

Fright is at the basis of the kind of thrill that people feel when they undertake activities that carry a certain risk–either real or imagined. For instance, many people feel a thrill when they suddenly have to speak for a large audience (Figure 6a), which is instigated by fear of social failure. A clear example of an imagined risk occurs when someone rides a rollercoaster (Figure 6b)–he knows the amusement park will make sure he is safe, but his body tells him otherwise. Fright can even play a role when there is a ‘positive risk’ involved, such as when people watch the lottery results in anticipation of winning. Fright is engaging because it focuses and energizes people to either avoid or control the source of danger. This transformation of attitude can be useful and pleasant when users have to engage in an uninspiring activity, or when they have to finish a task within a certain time. Furthermore, fright makes people experience their immediate situation as eventful and overpowering, which can be refreshing when they feel generally disinterested or bored. There are several thrilling children’s outdoor games on the market that feature a water-filled object, which is passed around between players. When the internal timer runs out, the person holding the device at that moment will get soaked (Figure 6c).

Figure 6. The thrilling quality: (a), (b), and (c).

The Challenging (Frustration + Satisfaction)

An obstacle elicits frustration; it is something standing in the way of achievement. On the other hand, without any obstacles to overcome, there would be no sense of achievement whatsoever. This paradoxical relation is central to mastering any skill, puzzle or game: people try to get rid of an obstacle and immediately look for a new one. For instance, the guitar pupil must perform endless exercises to learn new chords, which are, as soon as he has mastered them, succeeded by even more difficult ones (Figure 7a). A similar experience is offered by video games (Figure 7b), where the player has to test her agility, intelligence and creativity when going through increasingly difficult levels. An important design feature of challenging interactions is that people should always have an idea how to come closer to the end result–otherwise the experience will turn into sheer frustration. A case in point is the Rubik’s cube–people who are familiar with it might feel an irresistible urge to solve it, but those who have no clue what steps to take may twist it a few times fruitlessly and become disinterested. Frustrated people become focused and determined to solve the issue at hand, which is refreshing and useful when they are otherwise unmotivated or undirected towards a certain task. The Nekura Scramble LED Watch purposefully confronts users with an obstacle to make the activity of telling time more interesting (Figure 7c). By using a cryptic and unconventional way to display the time, the watch stands out in a saturated market.

Figure 7. The challenging quality: (a), (b), and (c).

Negative Emotions Signify Intriguing Boundaries

People have the basic need to understand the social and material world, themselves, and their relationship with the world (Frijda, 1986). Individuals are attracted to new, odd, or strange things because these situations can tell them something about the world or about themselves. The emotions in this category all notify the user that they are witnessing events that push the boundaries of what is acceptable physically, morally, or existentially.

The Eerie (Anxiety + Fascination)

Whereas fright (the thrilling) is a reaction to a clear danger in the here and now, anxiety is directed to ambiguous or intangible phenomena. Sometimes these anxieties have a functional basis, like being cautious of catching a disease in a contaminated area (Figure 8a), but they can also be considered ‘irrational’, like being afraid of the dark in a safe environment (Figure 8b). In both these experiences the whole surroundings can take on a mysterious and suspenseful quality. Another instance of this quality can be found in what Freud (1919) called ‘das Unheimliche’, or the uncanny: the feeling that one is observing something that is familiar, yet strange. Roboticist Masahiro Mori (1970) famously applied this phenomenon to describe the ‘uncanny valley’, which is the effect of objects resembling human beings almost, but not completely, which makes them very eerie (Figure 8c). People who experience anxiety become hyper vigilant towards themselves and their surroundings (Rhudy & Meagher, 2000), and become more suggestible to different explanations of their feelings, up to the point where they can even use superstition to explain the event. This effect can be helpful in design to make users more sensitive to events and information that they normally take for granted.

Figure 8. The eerie quality: (a), (b), and (c)

The Scandalous (Indignation + Fascination)

People love scandals. This is apparent in the popularity of sensational journalism (Figure 9a), but not restricted to that domain–serious news can also open with a story about the transgressions of an influential person. Scandals amaze, shock or even outrage people, but they also have an attractive quality that makes people want to know all the details involved. A scandal starts when someone violates a law or code of society, to which people react with indignation. This can be the violation of an actual law, marital rules, someone else’s trust (e.g., being betrayed), or social codes (e.g walking through the city nude). When a situation evokes enough indignation, it can even incite people to protest (Figure 9b). A scandal is enjoyable in part because it lets people experience an increased clarity and simplicity in the world: some moral issues may be ambiguous and multifaceted, but in a scandal it is clear who is right and wrong. However, because there is often not a direct way to deal with a scandal, it can bring out restlessness in people and an eagerness to discuss the case with others, which makes scandals a good conversation starter. Katrin Baumgarten (n. d.) showed with her teakettle ‘Raging Roger’ that products can also violate codes and act in a scandalous way (Figure 9c). Raging Roger rotates and squirts its contents at unsuspecting users.

Figure 9. The scandalous quality: (a), (b), and (c).

The Grotesque (Disgust + Fascination)

The grotesque is about being fascinated by something disgusting. This fascination is observable in people’s urge to slow down and get a glimpse of a car accident, or in the popularity of zombie movies (Figure 10a). Moreover, this quality can reveal itself in things that people regard as morally disgusting, which is part of the appeal of ‘shockumentaries’ and shock art (Figure 10b). The difference between indignation (the scandalous) and disgust (the grotesque) is that whereas social scandals harm a person’s idea of justice and harm/care, disgust is evoked when a person feels purity is being impaired, which “involves values and principles directed at protecting the sanctity of the body and soul” (Horberg, Oveis, Keltner, & Cohen, 2009, p. 964). People witnessing something disgusting will experience their situation with a direct and intriguing novelty, which evokes a simultaneous attraction and repulsion. Hemenover and Schimmack (2007)found that disgusting stimuli, when pushed far enough, may even be perceived as humorous, for instance when something exaggeratedly disgusting is shown in a movie. Meatbook was an interactive product installation with a grotesque character. The product had the form of a book with pages made from slices of real meat, which could sense the user and react by quivering, twitching, stretching and throbbing (Figure 10c). The installation was meant to evoke simultaneous revulsion and attraction that confronted the user with the contrast between the human body and technology (Levisohn, Cochrane, Gromala, & Seo, 2007).

Figure 10. The grotesque quality: (a), (b), and (c).

Negative Emotions Emphasize the Morality of Our Actions

Emotions are not always reactions to something that happens in the outside world–sometimes they are reactions to our own actions. Emotions like shame and pride are intuitive evaluations of a person’s own failure and success. These emotions can become rich if they include a paradox: a pleasure can become indulging if it is socially disapproved of, and an unpleasantness can elicit pride if it is clear that it will lead to greater good. In this sense, the following two qualities are each other’s opposites.

The Self-sacrificing (Reluctance + Pride)

Many activities in life, like doing household chores (Figure 11a) or tedious workouts can be unpleasant because people feel averse to engaging in them. However, the experience will become rich if it provides, in addition to the reluctance, the opportunity for people to realize that what they are doing is somehow good for them in the long run. In fact, the more effort or sacrifice is needed to complete a task, the more self-satisfaction people get during the task and afterwards. For example, a person that gets up early despite the enjoyable comfort of his bed may feel proud for not giving in to the temptation of sleeping late (Figure 11b). The reluctance makes people experience the world as a little harsher, bleaker, and more demanding environment. In addition, under the influence of the protective frame, a person’s attitude transforms to become sterner, more determined and disciplined. If design can facilitate this experience and attitude, it can be a useful motivator for people to engage in activities that are not necessarily pleasant, or as a means to improve someone’s self-respect. Manufacturers of very spicy hot sauces have clearly tapped into the self-sacrificing quality. Instead of focusing on good taste or high-quality ingredients, these sauces are primarily marketed as giving a painful sensation, with product names like ‘Sudden death’, ‘Beyond insanity’, and ‘100% pain’ (Figure 11c). The consumers of such products are obviously not repelled by the prospect of some pain, and even use them to feel better about themselves or to show off to others.

Figure 11. The self-sacrificing quality: (a), (b), and (c).

The Indulging (Shame + Desire)

Indulgence is about giving in to one’s forbidden desires. It occurs when someone engages in an activity that goes against a personal or social value, like overeating (against the value of moderation–Figure 12a) wallowing in laziness (against the value of diligence–Figure 12b) or loudly riding a motorbike in the morning (against the value of decency–Figure 12c). The negative emotion in this experience is shame, which people feel whenever they have violated a rule or custom. Paradoxically, it is the shame that determines whether an act is simply desirable or indulging. If the fruit is not forbidden, it is not half as seductive. For instance, people develop a strong preference for food that they have been prohibited to eat (Fisher & Birch, 1999; Mann & Ward, 2001). Thus, somehow the (expected) negative aspects of engaging in a certain activity will make the experience of the object or situation more seductive and attractive. This causes people to have a more impulsive and liberated attitude towards a situation, which can be interesting for design if the intention is to help people to ignore personal or social restrictions. The indulging is, just like the scandalous quality, about breaking rules. However, whereas the scandalous is about the user witnessing something or someone else breaking the rules, in the indulging it is the user himself who engages in the violation–and enjoys it.

Figure 12. The indulging quality: (a), (b), and (c).

Negative Emotions Enable Connection and Contemplation

In most literature, sadness is categorized as a prototypically negative emotion, and is often even thought to be the direct opposite of happiness (for example in the models of Plutchik, 2003 and Russell & Barrett, 1999). Evidently, deep feelings of sadness in reaction to misfortune in life, as well as sadness in depression are invariably unpleasant. Still, there are several emotional experiences related to sadness that are both rich and enjoyable. For instance, sadness is related to emotional experiences like longing and sympathy (Shaver, Schwartz, Kirson, & O’connor, 1987), nostalgia (Barrett et al., 2010), sentimentality (Tan & Frijda, 1999), and poignancy (Ersner-Hershfield, Carvel, & Isaacowitz, 2009). Furthermore, there appear to be links between sadness and aesthetic experiences. Most notably, Panksepp (1995) showed that the sensation of getting ‘chills’ (or ‘goose bumps’) from music is, contrary to common assumption, more related to sadness than to any other emotion. In our view, sadness can add a depth and significance to a person’s experience of the situation. For instance, feeling sad over the farewell of a good friend adds to the significance of the event. Ersner-Hershfield et al. (2009) demonstrated that people who were in a ‘poignant’ state of mind have “an intensified desire for, and ultimate experience of more positive emotion”, compared to people who were in a neutral state of mind. According to their theory, this leads people to pursue more emotionally meaningful goals in the here and now. Lastly, sadness promotes contemplation, as when people let their thoughts float while listening to overwhelming music. Studies on depression similarly link sadness to rumination (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), and even suggest it as the reason that artists with a tendency to depression are more creative (Verhaeghen, Joorman, & Khan, 2005). In addition, sadness has been shown to improve memory accuracy (Storbeck & Clore, 2005), which may indicate that it plays a conducive role in reflecting on one’s past.

The Unreachable (Longing + Dreaminess)

Desired things that are out of reach elicit a kind of sadness in people that goes by names like nostalgia, homesickness, and melancholy. The out of reach ‘things’ can be physical objects (e.g., an unaffordable dream house–Figure 13a), people (e.g., a lover who is abroad), or experiences (e.g., one’s own past childhood–Figure 13b). The experience becomes rich if the affected individual can somehow interact with the absent object, or a representation of it. Thus, people reminisce about the past by looking at photographs, exchange text messages with their distant lover and those dreaming of owning a sports car may collect posters and even miniature models of that car. Furthermore, the inherent sadness is not just negative - it also sets this experience apart from more trivial desires. Consider the opposite situation: if a person could buy or achieve everything she desires at any time, those things would arguably carry far less significance. Similarly, something that was once possessed but now lost can be cherished more than when it was still present, as expressed by the saying “you don’t know what you got ’til it’s gone”. The emotional experience affects a person’s attitude to become more connected to the object and it promotes ‘daydreaming’ and contemplating about the object or concept. ‘Heirloom’ is a product concept that stimulates people to get more attached to one of their possessions (Figure 13c). The user puts the chosen object inside a glass jar, out of reach, where it is preserved for generations to come. Every generation records their stories and memories related to the object, thus “transforming (…) a miscellaneous item into a meaningful object (Ferguson, n.d.).”

Figure 13. The unreachable quality: (a), (b), and (c).

The Sentimental (Poignancy + Enchantment)

Poignancy is the feeling of being overwhelmed with sadness over something that seems purely positive. For instance, a person may be moved to tears at her friend’s wedding (Figure 14a). This may seem strange at first consideration: why should there be any sadness involved in such a joyous experience? Tan and Frijda (1999) discuss this phenomenon, and argue that people feel overwhelmed by witnessing a certain goodness, grandeur or childlike purity in the world, which momentarily silences their cynical beliefs. This overwhelming feeling is accompanied by a sense of helplessness that triggers the tears and passive action tendency. Derived from their ideas, we think that the sentimental quality can be elicited by witnessing an act or event that symbolizes some greater virtue, like loyalty, bravery or diligence, especially if that act or event is against the odds or against expectation. The woman who is overwhelmed by her surprise party realizes that her friends have, against normal expectations, gone out of their way to make her happy, symbolizing the quality of their friendship. Witnessing acts of heroism, like a fireman sacrificing himself, can evoke a similar feeling because it involves virtues of altruism and bravery (Figure 14b). However, virtues do not always have to show themselves through people’s actions–they can also seem to originate in the world itself. Movies often make use of this idea, for instance, by showing that two people are ‘destined’ to be together, in spite of being obstructed by circumstances (Figure 14c). If they do finally end up together, against all odds, and show that ‘true love overcomes all obstacles’, the viewer can temporarily perceive the world as a more beautiful and good-natured place.

Figure 14. The sentimental quality: (a), (b), and (c).

The Application of the Approach

This section illustrates how the information in Table 1 can be used to design product concepts, by showing four short design cases that were carried out with several rich interaction qualities. The first four examples are part of a design session that was carried out by the first author to explore the usefulness and applicability of the different rich qualities, which yielded about 40 concepts in total. The last two examples are results of a two-week workshop that was carried out in London with Master degree students in Design for Interaction from the Technical University Delft (The Netherlands) and Master degree students in Industrial Design from Central Saint Martins School of Art and Design (United Kingdom). In this workshop, students used the rich experience approach to come up with innovative solutions for wicked social problems.

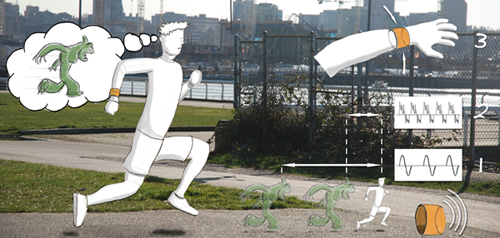

Brief 1: Making Jogging More Engaging

Jogging is a popular activity because it is an accessible and inexpensive way to exercise. However, in spite of the low physical threshold, people may struggle to keep jogging regularly after a few weeks because they experience it as tedious and monotonous. One of the reasons for this is that running lacks the engaging emotions that are evoked in sports with game elements, like football or tennis. So the first step in the approach was to find a quality that adds engagement and excitement to the experience of jogging. In this case, the thrilling quality seemed suitable, because it adds excitement and stimulation (transformation of perception), and it gives the user more focus and energy (transformation of attitude). The next step was to find a specific way to elicit fright through a threat (Table 1). The threat can occur at different moments in the interaction, for example before, during or after the jogging, and it can manifest itself in different ways, for example as a social threat (e.g., telling the user’s friends he has failed to go jogging), a psychological threat, or a physical threat. In this case, it was decided to manifest it as a psychological threat during the activity itself: the experience of being chased. This experience is one of the most frightening and activating experiences a person can have, and it is logically connected to the activity of running. The resulting concept was ‘Pursuit’ (Figure 15). This concept is a sweatband that people wear on their wrist, which uses a heart rate monitor to measure the user’s activation, and accelerometers to measure their physical activity. The user is chased by an imaginary pursuer the moment he or she starts running. This creature cannot be observed directly, but is represented by sound and tactile feedback. If the user is running in their pre-assigned pace, the sweatband will respond with comfortable intervallic beeps (1). When the user is starting to fall behind, the beeps will get more frequent and unpleasant to represent the creature getting closer (2). When it is even closer, the band will gradually contract around the wrist of the user (3), up to the point where the runner is ‘caught’, and the band will shut off completely. The fear of being chased and grabbed is intended to energize physically and stimulate mentally. To take the last step in the approach, the concept uses a detachment frame and a control frame: the source of danger is not real but represented through sound and touch, and the user is in control of the experience by managing their own speed.

Figure 15. Concept drawing of ‘Pursuit’ (the thrilling).

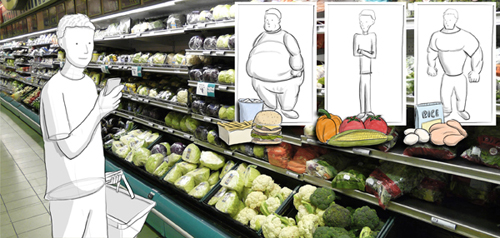

Brief 2: Making People More Aware of Nutritional Information

In many countries, food companies are required by law to display the nutritional values of food products on the packaging, so customers can make a more informed purchase decision. However, few people will have the time or motivation to read the packaging of every food item, as the information is often numerical and dry. The experience can be made richer by presenting the information in a more confronting way than current solutions do. Based on their ability to grab attention, two qualities seem to qualify: the eerie and the grotesque (Table 1). In this case the grotesque was chosen, because it has a more instantaneous impact, and because it is logically linked to the theme of food and eating. To elicit the disgust, a repulsive representation of the impact of food on the human body was chosen. The resulting concept, ‘The direct dietitian’ (Figure 16), is a digital nutrition assistant for smartphones that reacts directly to people’s purchase decisions. When the user starts shopping in a supermarket or grocery store, a normal looking cartoon character is displayed, which changes shape and expression according to the type of products the user puts in their cart. For instance, selecting only fatty items will make the character look obese, picking items with many proteins and minerals will make the character look more muscular, and if the user chooses mostly low-calorie food the character will look slimmer. Through a number of purchase decisions these cartoon characters will quickly look like a terribly obese, very skinny or extremely muscular and lean person. For the third step, the experience is reversed through a detachment frame, which is constructed by two sub-strategies: simplification (the screen shows cartoon figures rather than realistic people), and exaggeration (the exaggerated features of the characters can be taken less seriously than realistic bodily changes).

Figure 16. Concept drawing of ‘The direct dietitian’ (the grotesque).

Brief 3: Design Something That Makes a Restaurant Experience More Memorable

Even though going out to a nice restaurant is an experience that people seek out to have an enjoyable experience with good food and company, some restaurants wish to distinguish themselves from the competition by making the eating experience more unique. As good restaurants are commonly a bastion of social codes and etiquette, it can be an interesting exercise to play with some of these conventions. The indulging quality was found appropriate in this context because of its liberating and pleasure-seeking transformation. For the second step of the approach, it was chosen to motivate users to violate table manners as the way to elicit shame. The resulting concept is Fingerbite (Figure 17). The product is a silicon glove that people wear to eat with their hands in a hygienic way. This tool is intended as a complete replacement for standard cutlery. The outside of the fourth finger is serrated and sharp to afford cutting, and the fingers are webbed to easily scoop up soups. The shame of going against dining etiquettes is intended to make the activity more seductive and inviting, and creates a more liberated and lively atmosphere in the restaurant. The shameful behavior–touching food with one’s hands–is reversed by the physical barrier that the glove provides–a safety-zone frame. The interaction with the food and the resulting tactile sensation are equivalent to eating with bare hands, but the fact that the user is not in direct physical contact makes the experience acceptable.

Figure 17. Concept drawing of ‘Fingerbite’ (the indulging).

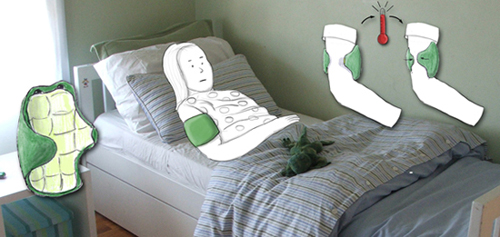

Brief 4: Consoling Feverish Children

Having a fever can be an unpleasant experience for children, as they have to be in bed for longer periods without much contact or activity. To make this experience a bit nicer and less lonely, the sentimental quality was applied, because of its transformation of perception–experiencing warmth and connectedness. The concept, Clinger (Figure 18), is a special kind of body-temperature measuring device. This soft, animal-like device can be pressed against the child’s arm to measure his or her temperature, and if the child has a fever, it will gently cling itself to the arm and stay there until the fever is over. In periods of high fever the device will softly purr to soothe the child. The product is intended to represent a little companion that stays with the child throughout the fever, regardless of any other ‘concerns’ the represented character might have. This touching idea is connected to virtues of companionship and loyalty, which elicits the poignancy. Furthermore, children who are ill in bed probably already have some sad feelings, which can now be partly redirected to the interaction with the product. The third step in the design approach is slightly different for the sentimental quality, as it inherently involves a perspective frame due to its involvement of virtues (see Table 1). In this case, there is an additional detachment frame present–because the product abstractly represents a loyal companion.

Figure 18. Concept drawing of ‘Clinger’ (the sentimental).

Student Project A: Encouraging Legal Downloading

Although illegal in most countries, media piracy (i.e., the illegal up–and download of software, videos, and music) is regarded by many people as a minor transgression rather than a crime. Countermeasures that aim to deter or scare people from downloading seem to have little effect, as the amount of illegal downloads increase every year with damages estimated in the billions. To make a positive change in this issue, the designers focused on a service that makes legally downloading music more attractive. The resulting concept, ‘Impulse’, is a smartphone application for users that have an account with existing channels like Spotify or iTunes, which promotes and gives away music to its users, if they are willing to do something in return (Figure 19). When the app senses that a number of people with similar music taste are in proximity of each other, a song starts playing simultaneously on each of their smartphones. Users are invited to react to this by dancing and singing to the song together–the more they engage in this assignment (measured by accelerometers and microphone), the more download credits they get. Users can choose to accept or reject the offer, but they have no influence over the type of song or its timing. The designers used the indulging and thrilling qualities to make the experience with the service seducing and stimulating, two effects that were found to work well with the young target group. The product evokes fright and shame by encouraging the user to stand out in a crowd and possibly look foolish to others. A safety-zone frame is provided by the fact that users are engaging in the activity together with others: a scare shared is a scare halved. A mockup version of the app was tested by students in a crowded London station. Most of the participants were at first reluctant to start dancing, but once a few people began, they all joined in voluntarily. Many passers-by stopped to look at the performance or take a picture. The participants noted afterwards that this outside attention motivate them to dance even more expressively. Most participants felt exhilarated after the event.

Figure 19. Representation of concept ‘Impulse’ (the thrilling and the indulging).

Student Project B: Increasing the Amount of Organ Donors

Worldwide, people who are in need of an organ donation exceed the number of organs available for transplants. Most countries only have a small percentage of the population registered as donors. The designers in the project ‘Donor hero’ wanted to enrich the experience of being and becoming an organ donor. The ‘experience gap’ that the project aimed to solve was that people who are registered as a donor do not feel heroic because they have not (yet) contributed a donor, whereas the people that donated are not around anymore to experience the results of their good deed. The concept is a street memorial for organ donors who were killed in an accident. The memorial, which is placed on the site of the accident, is the outline of the person with abstract representations and descriptions of the organs that were donated (Figure 20). Instead of focusing on details of their accident, it states, for example: Susan (28) saved 5 lives here on 20 June 2012. Two kinds of rich qualities are elicited in the interaction with the product. The slightly eerie quality of the human outline and the organs are meant to be mysterious and attract attention. For people who are registered as a donor, the memorial is meant to elicit the sentimental feeling that a fellow donor has deceased, who is now a hero. Because the memorial is a representation, it uses a detachment frame. The prototype was put in the street for a day and attracted considerable attention.

Figure 20. Representation of concept ‘Donor hero’ (the sentimental and the eerie).

Discussion

In this paper we have introduced a design approach to develop rich experience concepts. Evaluating, it seems indeed possible to deliberately use negative emotions to enrich product experiences. Furthermore, because it is a process that can be applied systematically, it is potentially interesting to apply in mainstream product development and as a method in design education. Apart from a general approach that outlines how designers can combine negative emotions and protective frames to create rich experiences, this paper also introduced ten rich qualities. The qualities originated by using the perspective of the framework to look at insights from three sources: emotional constructs in cultural products (i.e., movies, novels, music, games, etc.), phenomenological descriptions of mixed emotional experiences (Fokkinga & Desmet, 2012b), and scientific literature from the field of psychology and the humanities. The intention of introducing the qualities was to lower the threshold of working with the rich experience approach, by offering certain combinations of negative emotions and protective frames which we think are interesting and useful for product experiences. Furthermore, the qualities and their resulting transformations have been ‘pre-researched’, which saves designers the effort of doing the same. However, this does not mean that applying a quality to a product experience is a straightforward, uncreative task. Apart from choosing a quality to work with, it is also completely up to the designer in what way the negative emotion is manifested and how the protective frame is constructed. The specific user context that is designed for will also imply unique boundaries and opportunities that will influence the end result. Furthermore, the ten proposed qualities are by no means considered to offer an exhaustive list of possible rich experiences. We would therefore like to encourage designers and design researchers to come up with new rich qualities or describe qualities they may have used implicitly in past projects, and share them with the community. We are currently setting up a web-based platform to facilitate this exchange (Fokkinga, n.d.). The negative emotions that make up the rich qualities are all included in a typology that we are currently composing, which is based on thirty existing typologies, taxonomies, and lists of emotion definitions. The ten negative emotions in this paper are best defined and discussed in the following publications: The emotions fright (thrilling), frustration (challenging), anxiety (eerie), indignation (scandalous), shame (indulging), and disgust (grotesque) are all discussed by Frijda (1986, e.g., pp. 218-219). Maliciousness (sadistic) is a translation and interpretation of what Apter (2007, p. 119) describes as parapathic anger. Reluctance (self-sacrificing), in the meaning of ‘lacking enthusiasm’, and longing (unreachable) are both discussed by Johnson-Laird and Oatley (1989, p. 118). Lastly, poignancy (the sentimental) is covered by Ersner-Hershfield et al. (2009), and Tan and Frijda (1999). The positive emotions in the rich experience are all derived from a typology of positive emotions, which was developed as a design tool (Desmet, 2012).

Several components of the approach could be elaborated further to make the resulting product concepts better and more predictable. For instance, it seems that there should be some balance between the strength of the negative emotion and the protective frame. If the negative emotion is too strong and the protective frame too weak, the resulting experience will be predominantly negative. For example, if the wristband of the ‘pursuit’ concept would start to contract around the runner’s arm so tightly that it causes pain, the detachment frame would fail and the runner could get genuinely scared of the sweatband, instead of the pursuer it represents. On the other hand, if a protective frame is too strong or a negative emotion too weak, the resulting experience can become boring or even laughable. For instance, if the gloves of the ‘Fingerbite’ concept would only be used to eat food that is not very daring to touch without gloves, like bread or snacks, the user might feel ridiculous for using them. More research on the intensity of negative emotions and protective frames could give additional guidelines to understand the construction of rich experiences.

Apart from the fact that rich experiences have different effects, and should thus be used for different design opportunities, we also found some overarching rules of applicability. In general, the qualities grotesque, scandalous, eerie, sentimental, and thrilling are easier to implement, because they only require the attention and perception of the user: the grotesque is, for instance, elicited as soon as the user perceives something disgusting. Conversely, the qualities challenging, self-sacrificing, unreachable, sadistic, and indulging require the user to engage in a certain activity before they manifest themselves: a product experience can only be self-sacrificing if the user is willing to engage in the aversive activity. Secondly, it seems that some qualities are more subject to cultural and personal differences than others. For instance, all people are hard-wired to find certain things disgusting or frightening, whereas what is considered indulging or sentimental may vary based on cultural and personal values: a movie that truly moves some people, might be regarded as tasteless by others.

When designing for emotion, there is always a subjective dimension that complicates a prediction of the resulting experience (Desmet, 2008). In one sense emotions are universal, because they are reliably evoked by the same relational causes: shame is for instance always evoked by a personal transgression. On the other hand emotions are subjective, because, by the same example, the actions that people consider to be personal transgressions can differ heavily between people and cultures. For example, the ‘Fingerbite’ concept would probably not evoke shame or a rich experience if it were introduced in a culture where it is already customary to eat with bare hands. Thus, the implementations of the steps of the approach should always be informed by a solid understanding of the culture and context that is designed for, and be followed by tests to make sure that the final result has the intended effect.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the Creative Industry Scientific Program (CRISP), which focuses on the design of product–service systems as a means to stimulate the continuing growth of the Dutch Design Sector and Creative Industries. The CRISP program is partially sponsored by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science.

This research was supported by MAGW VIDI grant number 452-10-011 of The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), awarded to P. M. A. Desmet.

References

- Apter, M. J. (2007). Reversal theory: The dynamics of motivation, emotion, and personality (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oneworld.

- Aristotle. (2009). In D. Ross (Ed.), The nicomachean ethics (L. Brown, Trans.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Arrasvuori, J., Boberg, M., & Korhonen, H. J. (2010). Understanding playfulness: An overview of the revised playful experience (PLEX) framework. Paper presented at the 7th Conference on Design and Emotion. Chicago, IL.

- Barrett, F. S., Grimm, K. J., Robins, R. W., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Janata, P. (2010). Music-evoked nostalgia: Affect, memory, and personality. Emotion, 10(3), 390-403.

- Baumgarten, K. (n.d.). Raging Roger, the spitting teapot. Retrieved April 30, 2013, from http://katrinbaumgarten.de/thisthat/raging-roger-the-spitting-teapot/

- De Quervain, D. J. F., Fischbacher, U., Treyer, V., Schellhammer, M., Schnyder, U., Buck, A., & Fehr, E. (2004). The neural basis of altruistic punishment. Science, 305(5688), 1254-1258.

- Desmet, P. M. A. (2002). Designing emotions (Doctoral Dissertation). Delft, the Netherlands: Delft University of Technology.

- Desmet, P. M. A. (2008). Product emotion. In H. N. J. Schifferstein, & P. Hekkert (Eds.), Product experience (pp. 379-398). San Diego, CA: Elsevier.

- Desmet, P. M. A. (2012). Faces of product pleasure: 25 positive emotions in human-product interactions. International Journal of Design, 6(2), 1-29.

- Ellsworth, P. C., & Scherer, K. R. (2003). Appraisal processes in emotion. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 572-595). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Ersner-Hershfield, H., Carvel, D. S., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2009). Feeling happy and sad, but only seeing the positive: Poignancy and the positivity effect in attention. Motivation and Emotion, 33(4), 333-342.

- Ferguson, N. G. (n.d.). The Heirloom. Retrieved April 30, 2013, from http://www.nikkigeorgeferguson.com/Design/The_Heirloom.html

- Fisher, J. O., & Birch, L. L. (1999). Restricting access to palatable foods affects children’s behavioral response, food selection, and intake. The American Journal of Jlinical Nutrition, 69(6), 1264-1272.

- Fokkinga, S. F. (n.d.). Rich experience qualities. Retrieved October 1, 2011, from http://studiolab.ide.tudelft.nl/diopd/library/tools/rich-experience-qualities/

- Fokkinga, S. F., & Desmet, P. M. A. (2012a). Darker shades of joy: The role of negative emotion in rich product experiences. Design Issues, 28(4), 42-56.

- Fokkinga, S. F., & Desmet, P. M. A. (2012b). Meaningful mix or tricky conflict? A categorization of mixed emotional experiences and their usefulness for design. In: J. Brassett, P. Hekkert, G. Ludden, M. Malpass, & J., McDonnell (Eds.), Proceedings of the 8th International Design and Emotion Conference. Central Saint Martin College of Art & Design, London, UK, 11-14 September 2012.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society of London: Series B, Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367-1378. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

- Freud, S. (2005). Das Unheimliche [The Uncanny]. Gesammelte Werke, Vol. XII: Werke aus den Jahren 1917-1920. pp. 229-268. Imago Publishing Co., Ltd., London.

- Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Hassenzahl, M. (2010). Experience design: Technology for all the right reasons. San Francisco, CA: Morgan and Claypool.

- Hemenover, S. H., & Schimmack, U. (2007). That’s disgusting!..., but very amusing: Mixed feelings of amusement and disgust. Cognition and Emotion, 21(5), 1102-1113.

- Horberg, E., Oveis, C., Keltner, D., & Cohen, A. B. (2009). Disgust and the moralization of purity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 963-976.

- Johnson-Laird, P. N., & Oatley, K. (1989). The language of emotions: An analysis of a semantic field. Cognition and Emotion, 3(2), 81-123.

- Jordan, P. W. (2000). Designing pleasurable products: An introduction to the new human factors. London, UK: Taylor & Francis.

- Knutson, B. (2004). Sweet revenge? Science, 305(5688), 1246-1247.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Lerner, J. S., & Keltner, D. (2000). Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgement and choice. Cognition and Emotion, 14(4), 473-493.

- Levisohn, A., Cochrane, J., Gromala, D., & Seo, J. (2007). The meatbook: Tangible and visceral interaction. In B. Ullmer, A. Schmidt, E. Horncker, C. Hummels, R. J. K. Jacob, & E. van den Hoven (Eds.), Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Tangible and Embedded Interaction (pp. 91-92). New York, NY: ACM press.

- Ludden, G. D. S. (2008). Sensory incongruity and surprise in product design (Doctoral Dissertation). Delft, the Netherlands: TU Delft.

- Mann, T., & Ward, A. (2001). Forbidden fruit: Does thinking about a prohibited food lead to its consumption? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29(3), 319-327.

- Morawe, V., & Reiff, T. (n.d.). The artwork formerly known as PainStation. Retrieved March 1, 2012, from http://www.painstation.de/

- Mori, M. (1970). The uncanny valley. Energy, 7(4), 33-35.

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569-582.

- Norman, D. A. (2004). Emotional design: Why we love (or hate) everyday things. New York, NY: Basic Civitas Books.

- Panksepp, J. (1995). The emotional sources of “chills” induced by music. Music Perception, 13(2), 171-207.

- Plutchik, R. (2003). Emotions and life: Perspectives from psychology, biology, and evolution. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Rhudy, J. L., & Meagher, M. W. (2000). Fear and anxiety: Divergent effects on human pain thresholds. Pain, 84(1), 65-75.

- Rucker, D. D., & Petty, R. E. (2004). Emotion specificity and consumer behavior: Anger, sadness, and preference for activity. Motivation and Emotion, 28(1), 3-21.

- Russell, J. A., & Barrett, L. F. (1999). Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(5), 805-819.

- Sartre, J. -P. (1939/1962). Sketch for a theory of the emotions (P. Mairet, Trans.). London, UK: Methuen.

- Shaver, P., Schwartz, J., Kirson, D., & O’connor, C. (1987). Emotion knowledge: Further exploration of a prototype approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(6), 1061-1086.

- Storbeck, J., & Clore, G. L. (2005). With sadness comes accuracy; With happiness, false memory: Mood and the false memory effect. Psychological Science, 16(10), 785-791.

- Tan, E. S. H. (1996). Emotion and the structure of narrative film: Film as an emotion machine (B. T. Fasting, Trans.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Tan, E. S. H., & Frijda, N. H. (1999). Sentiment in film viewing. In C. R. Plantinga & G. M. Smith (Eds.), Passionate views: Film, cognition, and emotion (pp. 48-64). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Verhaeghen, P., Joorman, J., & Khan, R. (2005). Why we sing the blues: The relation between self-reflective rumination, mood, and creativity. Emotion, 5(2), 226.